Abstract

Background

Public health and clinical recommendations are established from systematic reviews and retrospective meta-analyses combining effect sizes, traditionally, from aggregate data and more recently, using individual participant data (IPD) of published studies. However, trials often have outcomes and other meta-data that are not defined and collected in a standardized way, making meta-analysis problematic. IPD meta-analysis can only partially fix the limitations of traditional, retrospective, aggregate meta-analysis; prospective meta-analysis further reduces the problems.

Methods

We developed an initiative including seven clinical intervention studies of balanced energy-protein (BEP) supplementation during pregnancy and/or lactation that are being conducted (or recently concluded) in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, India, Nepal, and Pakistan to test the effect of BEP on infant and maternal outcomes. These studies were commissioned after an expert consultation that designed recommendations for a BEP product for use among pregnant and lactating women in low- and middle-income countries. The initiative goal is to harmonize variables across studies to facilitate IPD meta-analyses on closely aligned data, commonly called prospective meta-analysis. Our objective here is to describe the process of harmonizing variable definitions and prioritizing research questions. A two-day workshop of investigators, content experts, and advisors was held in February 2020 and harmonization activities continued thereafter. Efforts included a range of activities from examining protocols and data collection plans to discussing best practices within field constraints. Prior to harmonization, there were many similar outcomes and variables across studies, such as newborn anthropometry, gestational age, and stillbirth, however, definitions and protocols differed. As well, some measurements were being conducted in several but not all studies, such as food insecurity. Through the harmonization process, we came to consensus on important shared variables, particularly outcomes, added new measurements, and improved protocols across studies.

Discussion

We have fostered extensive communication between investigators from different studies, and importantly, created a large set of harmonized variable definitions within a prospective meta-analysis framework. We expect this initiative will improve reporting within each study in addition to providing opportunities for a series of IPD meta-analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Maternal and child undernutrition continues to be a massive public health issue that needs more attention. Many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to test the effects of maternal nutrition interventions on pregnancy and postpartum outcomes [1,2,3,4]. One such intervention with a growing evidence base is balanced energy-protein (BEP) supplementation. BEP products are ready-to-eat or prepared foods, typically biscuits or powders, that contain energy with a balanced amount of protein intended to supplement the home diet. When designed for use in pregnancy, they often contain micronutrient fortification or a multiple micronutrient supplement in tandem.

Globally, there is a high burden of underweight among women at the start of pregnancy (240 million based on body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 kg/m2) [5]. Providing BEP to increase intake of calories and protein during gestation may increase offspring birthweight in undernourished women [4, 6, 7] as well as reduce the risk of stillbirth and small for gestational age (SGA) [4, 7,8,9,10]. Further, there could be health benefits for the mother, including improved weight gain [11] and reduced risk of anemia [12, 13]. Beginning in 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended BEP supplementation during pregnancy in populations with a high prevalence (> 20%) of pregnant women who are undernourished, to decrease the risk of stillbirth and SGA [14]. However, the evidence base informing this recommendation included a wide range of BEP products and nutrient content, creating challenges around implementation.

Over 20 years ago, the need for harmonizing nutrients in an intervention was recognized for micronutrients. An expert panel was convened, and the result was the development of a formulation for a multi-micronutrient supplement for pregnant women from LMICs, called the United Nations International Multiple Micronutrient Preparation (UNIMMAP) [15]. The group recommended that this antenatal supplement, now with a similar nutrition composition, be tested in multiple trials. Similarly, given the heterogeneity in BEP supplements, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) convened an expert panel in 2016 to create guidelines for macronutrient and micronutrient composition of BEP supplements [16]. As part of the consultation, the panel explored the “use-case” for BEP distribution and consumption and recommended that next steps include developing the food products and testing the impact on health outcomes among multiple trials.

Following this guidance, the BMGF funded several intervention studies planning to test the effect of BEP in preconception, pregnancy, and/or lactation in countries in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. These studies were all designed with BEP supplements that followed the nutrient content targets from the 2016 guidance [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], but had independent investigators and were not coordinating together. Studies were specifically funded in multiple countries, given that some heterogeneity across studies (e.g., different environmental factors, diets, and range of nutritional status) is helpful to find answers that can be applicable across diverse populations. However, differences in data and specimen collection techniques, calculations, definitions, and laboratory methods can limit the ability to conduct meta-analyses and compare findings across studies. The need to harmonize protocols has long been recognized but historically occurred through inherently multi-site studies such as the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference study [30] or the Etiology, Risk Factors and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health and Development (MAL-ED) study [31]. A relatively new framework, called prospective meta-analysis, has emerged to create a process that identifies planned or ongoing studies and forms a collaboration ahead of synthesizing and analyzing pooled data [32, 33].

With forethought on the opportunity to conduct prospective meta-analysis with individual participant data (IPD) from these planned or ongoing studies, the current BEP harmonization initiative was born. The IPD approach allows us to gain insights into BEP effectiveness and the effect of individual-level moderators on treatment outcomes, and the prospective approach allows us to collaborate as a large group and harmonize variables. As described by Seidler et al., “the methodology [for prospective meta-analysis] remains rare, novel, and often misunderstood” [32]. Therefore, our objective in the current paper is to describe the methods of harmonizing data collection and variable definitions and prioritizing research questions for prospective IPD meta-analyses.

Methods

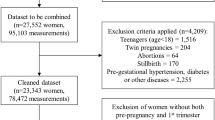

The Maternal BEP Studies Harmonization Initiative is an ongoing prospective meta-analysis effort that includes harmonizing, optimizing, and enhancing aspects of maternal BEP supplementation studies during pregnancy and lactation for maternal health and infant growth. The methods described here chronicle the initial phase of the initiative to harmonize selected variable definitions (including case definitions and outcomes) and develop research questions for IPD meta-analysis. Methods for individual studies are not part of the current paper but study registry information is included in Table 1, and protocols are or will be published separately by the research team for each study [17,18,19,20,21, 26,27,28,29]. The long-term goal of the initiative is to conduct prospective, IPD meta-analyses to examine the effects of maternal BEP supplementation on pregnancy and postpartum outcomes for mother and child.

Participating studies

There are two main approaches for identifying studies for prospective meta-analysis. The first is a systematic search of trial registries, similar to a systematic review of the literature that would be done for a retrospective meta-analysis [32]. The second is to establish inclusive discussions with investigators of planned or ongoing studies, ideally from countries around the world, and set up a collaboration [33]. We followed the second approach because there were already connections between investigators that were funded by the BMGF to examine maternal BEP supplementation, and the study sites represented five different LMIC settings in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

The initiative was funded by the BMGF and began in late 2019. Initially, five principal investigators (PIs) for six studies in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, India, Nepal, and Pakistan (2 trials) were invited to participate (Table 1). A seventh BEP study in India was added in October 2020, and although the trial had recently completed and would not be able to change data collection, it was closely aligned with the other studies and some harmonization was still possible through IPD meta-analysis. Also, the PI of the added trial was already part of the harmonization initiative as a co-investigator on another trial.

Ethics

Each study carried out methods in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and all protocols were first approved by the appropriate ethical boards, locally and at the home institution of the PI (when different from the site location). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants and details are published by each individual study. The harmonization work of the initiative, described here, was solely with study protocols and did not include any human data. Our future meta-analysis will be conducted with de-identified data and has been deemed “not human research” by the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board (STUDY00017249).

Initiative members

This initiative included the investigators from individual trials, a technical advisory group (TAG), and a coordinating team. Among the main contributors, the study PIs are considered the decision makers, and collectively make the final call on aspects of harmonization. The TAG was established with five experts in maternal and child nutrition research in LMICs, and they are consulted on an ongoing basis for input and advice. The coordination and management team was created under the direction of Dr. Gernand at Penn State, an investigator with experience in maternal nutrition trials in LMICs but external to the current BEP studies. The coordination team plans and guides the work, ensuring the initiative moves forward, and synthesizes and investigates details. The BMGF has served in a facilitation role throughout, including funding and organizing the workshop described below.

Participating members of this initiative covered a wide range of research, laboratory, and clinical expertise. Individuals included maternal, obstetric, perinatal, and pediatric clinician-researchers, pregnancy; lactation, and nutrition experts; and trialists, statisticians, and epidemiologists with representation across North America, Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Australia.

Workshop

After key members were identified and recruited, activities began and continue to the present. The main activities included an in-person workshop, remote meetings, and surveys – all conducted with members of the initiative (co-authors on this manuscript). The two-day workshop was held at the BMGF headquarters in Seattle, Washington in February 2020. In addition to initiative members described above, researchers from around the world were in attendance, including experts in the fields of nutrition, epidemiology, the gut microbiome, biomarker discovery, neurodevelopment, pregnancy, fetal development, and pediatrics.

The workshop had three main goals, each addressed in a separate, facilitated session:

-

1)

Create a harmonized variable list with common definitions

-

2)

Align on a harmonized protocol for biospecimen collection and analysis

-

3)

Discuss the potential for harmonized neurodevelopment assessment

Ahead of the workshop, the coordination team collected all study protocols and created charts and tables to document the pre-existing similarities and differences. These files were shared at the workshop with all participants. During the workshop, large posters were displayed to aid in mapping out harmonized variable definitions. Posters included existing definitions and measurement protocols from each study and existing or standard definitions from the literature and authoritative health agencies or professional societies along with space to draw out new ideas.

Substantial progress on all three goals was achieved and next steps were discussed. Throughout the workshop, teams expressed an interest in creating a network with regular meetings to discuss problems encountered and operational difficulties in addition to the harmonization work. At the end of the workshop, harmonization on the initial variables list was in place and a list of additional variables to align was created. Harmonizing biospecimen collection and neurodevelopment assessment also occurred but is not part of the current paper because the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic caused changes and reductions in the ability of most trials to collect biospecimens and/or continue with plans for neurodevelopment assessment. Further, other groups and laboratories were funded to measure and examine these components.

Follow up meetings

From March to May 2020, regular, remote meetings occurred (via Microsoft Teams) approximately every 2 weeks to discuss additional variables and details of harmonization. From the end of May to mid-July there was a pause on group meetings to update the reports and variables. From August 2020 to the present, meetings occur every 4 to 8 weeks. TAG members were consulted outside of regular group meetings due to the difficulty of finding a common meeting time for the large number of people involved, and because it was useful to get input from TAG members separately.

Surveys were utilized between meetings to query teams individually and allow feedback ahead of (and uninfluenced by) group discussions. Survey topics included degree of agreement with proposed variable definitions, the need for more discussion of variables either individually or as a group, and the feasibility and use of newly created variable definitions. These surveys were key to coordination, planning efficient remote meetings, and collecting detailed information from teams.

Similarities and differences between studies

In the preliminary assessment of overlap between studies, similarities and differences were identified. Per the goal of the initiative, all studies were testing BEP supplementation compared to a control group that did not receive BEP (but did receive the standard of care for pregnancy/lactation/infancy). All studies were collecting maternal and infant anthropometry, and all studies were using ultrasound-based gestational dating during pregnancy. Primary outcomes were similar across studies: infant size at birth for pregnancy studies and infant size and growth velocity (change in weight or length) at 6 months for lactation studies. We identified the following major differences across studies: the randomization design (individual vs. cluster, different number of intervention arms), other interventions coupled with BEP, timing of enrollment during pregnancy (early vs. mid), timing of anthropometry measurements, and timing and number of biospecimens collected.

Harmonization of variables

At the workshop, a total of nine outcome variables (or variable clusters) were originally slated for discussion in three breakout groups with representation from each study team and at least one member of the TAG: birth weight, birth length, birth head circumference, infant anthropometry, maternal anthropometry, stillbirth, infant mortality, maternal mortality, and gestational age. This first set of variables was selected based on overlap of outcomes that were primary or secondary objectives of individual studies or important rare outcomes for which IPD meta-analysis would allow estimation of the effect of BEP.

Each workshop session brought about new ideas for additional variables to collect or harmonize across sites. Examples that were brought up in multiple sessions included: SGA, short-for-gestational age, large-for-gestational age, preterm birth (spontaneous versus induced), preeclampsia, and causes of maternal death. There were also multiple discussions around capturing the details of delivery (e.g., Cesarean section), maternal morbidities, and corresponding international classification of diseases (ICD) codes (although we did not link ICD codes to variables). These workshop discussions formed agendas for variables to discuss in the first set of remote meetings, and during the months of remote meetings, we continued to work through discussions of variables that the group determined to be important and feasible to harmonize. Priority was given to maternal and infant health outcomes; key variables that help to understand or describe the outcomes (e.g., gestational age, mode of delivery) or intervention (e.g., nutrient intake, food insecurity); and variables identified as potential effect modifiers (e.g., pre-pregnancy BMI).

For each variable, we considered a range of details to harmonize including timing, measurement tool, number of measurements, and quality control. Loosely, our framework for alignment at this stage covered levels 1–3, and occasionally level 4, for details to include for outcomes in a ClinicalTrials.gov registry [34]. For example, newborn anthropometry was like a domain, one of the specific measurements was birth weight (with details on how to conduct the measurement), and the specific metric was the gestational age- and sex-specific z score, if drawing parallels with the ClinicalTrials.gov outcome levels.

Ultimately, more than sixty variables were reviewed, discussed, and a group consensus reached for a definition and variable name (Supplementary Table 1). These harmonized variables generally fall into eight domains/categories: anthropometry, pregnancy characteristics, pregnancy complications, labor and birth outcomes, mortality, food insecurity and infant feeding, maternal dietary intake, and supplement adherence (compliance). After our variable harmonization process, we were made aware of the core outcome measures in effectiveness trials (COMET) initiative, which establishes core (or minimum) sets of outcomes for specific areas of health [35]. To our knowledge, the main related COMET set is the pregnancy and childbirth standard set [36]. Our developed harmonized variables are minimally overlapping with these because our variables are specific to LMIC settings and focused on those needed for studies of BEP supplementation while theirs were established for studies evaluating perinatal care.

Variables beyond the scope of harmonization

During meetings, there were many variables discussed in relation to the planned IPD meta-analyses that the group decided not to harmonize. In some cases, variables were too complicated or different across study settings (e.g., socio-economic status). In other cases, it seemed like variables were too far outside the goals of the IPD meta-analysis, and spending time to align definitions would likely not improve the IPD meta-analyses in a meaningful way (e.g., sepsis). There was a desire across study teams to harmonize adherence to the intervention, but decisions on the best way to measure adherence were not clear and certain field methods in use, e.g., direct observation of supplement consumption, were not feasible in all settings. Variables that were considered but ultimately not harmonized included: wealth index, socio-economic status, maternal education/literacy, maternal or infant sepsis, maternal postpartum hemorrhage, severe features of preeclampsia, and additional details of labor and delivery (beyond those in Supplementary Table 1). Finally, maternal postpartum depression was planned for each study, using either the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [37] or the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [38] depression interview. While there was group discussion about these depression scales, including field practices and advice on their use, we did not decide to harmonize a depression variable particularly because data collection was already in progress using the different scales.

As in traditional meta-analysis, we still plan to use variables that are defined in different ways (i.e., not harmonized), and we will leverage the full datasets to create variables that are as closely aligned as possible. For example, with socio-economic status, we can use composite indices created within each trial to combine tertiles or quartiles of income/wealth.

Research questions for IPD meta-analyses

The focus of the harmonization effort has been planning for IPD meta-analyses. Early in the process, the full group discussed, vetted, and prioritized objectives for a series of IPD meta-analyses. We wrote these out in the form of research questions, such as, what is the effect of BEP supplementation during pregnancy on the risk of small-for-gestational age? Or what is the effect of BEP supplementation during lactation on infant length at 6 months of age?

The objectives clustered into four groups:

-

1.

Common or continuous outcomes (those that studies are individually powered to address)

-

2.

Rare outcomes (those that studies are not individually powered to address)

-

3.

Harmonized sub-studies (not discussed in the current paper)

-

4.

Stratified analyses (to identify groups where BEP could provide the largest benefit)

Common and rare outcomes are listed in Table 2 by the life stage of BEP supplementation. For stratified analysis, the following effect modifiers were selected to examine: maternal education, age, parity, height, BMI, and mid-upper arm circumference, adherence to BEP, geography, and household-level food insecurity.

Discussion

Lessons learned

We describe here the initial process for a prospective meta-analysis of seven LMIC studies across five countries testing BEP intervention during pregnancy and/or lactation to improve maternal and infant outcomes. This collaborative work leveraged and integrated knowledge generation beyond that which would have been achievable by individual studies alone. Such efforts are challenging to undertake outside of “multi-country/site” studies and across multiple PIs, timelines, and independent grant mechanisms, but are becoming more common [39,40,41,42]. This harmonization effort found extremely collaborative investigators and a coordination team supported by a visionary funder. Important elements had to come together in the early stages of grant-making to make this work possible. An in-person workshop combined with ongoing meetings and surveys allowed for open communication and prioritization of the work. The result is a core set of over sixty harmonized variables.

Prior harmonization and standardization efforts

Researchers and clinicians have long tried to raise awareness about the need for standard definitions and protocols, particularly for maternal and infant health [43, 44]. The COMET initiative was established in 2010 to develop “core outcome sets” to extend the concept of standardization to establish a minimum set of outcomes to measure for health conditions [45]. Standard definitions are commonly published and reviewed by authoritative bodies such as the WHO, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Brighton Collaboration, and we consulted these sources as a starting point for all variables. We also looked at other global collaborations, such as the International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems (INOSS) for the study of rare pregnancy problems [46], the Global Pregnancy Collaboration (CoLab) for the study of preeclampsia [47], and the recently created International Milk Composition (IMiC) consortium (https://www.milcresearch.com/imic.html) for the harmonization of methods for human milk analysis (two of the studies in this group are also participating in IMiC).

Ongoing work during the COVID-19 pandemic

The harmonization process has been highly interactive, with open sharing between investigators. The group has benefited from the incredible depth of knowledge from the research teams’ members and the group of advising experts. Many researchers involved in this initiative have decades of experience in running nutrition trials in LMIC settings. The COVID-19 pandemic presented enormous challenges for the individual studies and field work, but minimal disruption for the initiative. Participation levels were quite high at the beginning of the pandemic and have remained as such. Effective remote meetings were possible via Microsoft Teams, particularly by sharing slides that detailed discussion topics and questions and by using the chat feature in addition to vocal comments. We share a list of lessons learned in Table 3.

While key variables have been harmonized, some final questions (e.g., denominators for mortality rates) will continue to be discussed for analysis. Next steps in the work include establishing a composite data dictionary, developing detailed data analysis plans, and conducting the series of IPD meta-analyses. These steps will require further discussion of variables, particularly those that may be included in analysis but that were not harmonized (e.g., maternal education).

Pros and cons of the harmonization phase

This harmonization initiative has many strengths. As previously discussed, the wide-ranging and long-standing expertise of investigators within each individual study was critical during the vetting and final decision making of variable definitions. Often there was an important consideration that was prompted by a single group member. The TAG, as a separate body from the study investigators, strengthened the process by providing insight from experts that were not currently conducting BEP studies. Additionally, a coordination and management team was central in keeping the harmonization process going, keeping the large group connected and engaged, and doing necessary background work to glean details important for complicated or difficult to define variables.

We encountered several challenges, some of which we could not resolve fully. While we maintained high standards for developing rigorous, detailed definitions of variables, there were three key scenarios which may affect our final analysis: 1) investigators agreed on a definition knowing that it was ideal but that not all studies could meet the definition, 2) investigators agreed on a definition that was not ideal, but that was practical across settings, and 3) investigators agreed that a common definition was too hard to reach across studies (often due to the level of clinical information available). Sometimes it was very difficult to reach agreement, and in these cases, the coordination team gathered individual input (which was kept anonymous) and re-visited details of other published definitions and protocols to present new information and choices to the whole group. In every case, a solution was agreed upon. If similar opportunities arise for other analogous studies, we highly advocate for a harmonization effort to be conducted and have key recommendations (Table 4).

Conclusion

In our harmonization effort, as part of an initiative for prospective IPD meta-analysis of pregnancy and lactation studies, we had highly collaborative investigators, along with a coordination team and TAG that facilitated detailed technical conversations and agreement on variable definitions across diverse country settings. Among numerous investigators for seven RCTs of maternal BEP supplementation in five different LMICs, we successfully harmonized over sixty variables related to maternal and infant health. We hope this work is a valuable resource to other researchers and clinicians as we collectively work to improve the health of mothers and infants around the globe.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BEP:

-

Balanced energy-protein supplementation

- BMGF:

-

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CoLab:

-

Global Pregnancy Collaboration

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- INOSS:

-

International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems

- IMiC:

-

International Milk Composition

- IPD:

-

Individual participant data

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle- income countries

- MAL-ED:

-

Etiology, Risk Factors and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health and Development

- PIs:

-

Principal investigators

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- TAG:

-

Technical advisory group

- UNIMMAP:

-

United Nations International Multiple Micronutrient Preparation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Gernand AD, Schulze KJ, Stewart CP, West KP, Christian P. Micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy worldwide: health effects and prevention. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(5):274–89.

von Salmuth V, Brennan E, Kerac M, McGrath M, Frison S, Lelijveld N. Maternal-focused interventions to improve infant growth and nutritional status in low-middle income countries: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256188.

Roth DE, Leung M, Mesfin E, Qamar H, Watterworth J, Papp E. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: state of the evidence from a systematic review of randomized trials. BMJ. 2017;359:j5237.

Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes: effect of balanced protein-energy supplementation. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(s1):178–90.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1377–96.

Mousa A, Naqash A, Lim S. Macronutrient and micronutrient intake during pregnancy: an overview of recent evidence. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):443.

Ota E, Hori H, Mori R, Tobe-Gai R, Farrar D. Antenatal dietary education and supplementation to increase energy and protein intake. Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015. Available from: https://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD000032.pub3. Cited 2021 Sep 29.

Visser J, McLachlan MH, Maayan N, Garner P. Community-based supplementary feeding for food insecure, vulnerable, and malnourished populations - an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD010578.

da Silva Lopes K, Ota E, Shakya P, Dagvadorj A, Balogun OO, Peña-Rosas JP, et al. Effects of nutrition interventions during pregnancy on low birth weight: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(3):e000389.

Lassi ZS, Padhani ZA, Rabbani A, Rind F, Salam RA, Das JK, et al. Impact of dietary interventions during pregnancy on maternal, neonatal, and child outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):531.

Stevens B, Buettner P, Watt K, Clough A, Brimblecombe J, Judd J. The effect of balanced protein energy supplementation in undernourished pregnant women and child physical growth in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(4):415–32.

Leroy JL, Olney D, Ruel M. Tubaramure, a food-assisted integrated health and nutrition program in Burundi, increases maternal and child hemoglobin concentrations and reduces Anemia: a theory-based cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. J Nutr. 2016;146(8):1601–8.

Leroy JL, Olney D, Ruel M. Tubaramure, a food-assisted integrated health and nutrition program, reduces child stunting in Burundi: a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. J Nutr. 2018;148(3):445–52.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: World health Organization; 2016. p. 196.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations University (UNU). Composition of a multi-micronutrient supplement to be used in pilot programmes among pregnant women in developing countries: report of a United Nations Children’s fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations University workshop. New York: UNICEF; 1999. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/75358. Cited 2021 Sep 29.

Members of an Expert Consultation on Nutritious Food Supplements for Pregnant and Lactating Women. Framework and specifications for the nutritional composition of a food supplement for pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in undernourished and low income settings. Gates Open Res. 2019;3(1498):1498.

Muhammad A, Shafiq Y, Nisar MI, Baloch B, Yazdani AT, Yazdani N, et al. Nutritional support for lactating women with or without azithromycin for infants compared to breastfeeding counseling alone in improving the 6-month growth outcomes among infants of peri-urban slums in Karachi, Pakistan—the protocol for a multiarm assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial (Mumta LW trial). Trials. 2020;21(1):756.

Muhammad A, Fazal ZZ, Baloch B, Nisar I, Jehan F, Shafiq Y. Nutritional support and prophylaxis of azithromycin for pregnant women to improve birth outcomes in peri-urban slums of Karachi, Pakistan—a protocol of multi-arm assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial (Mumta PW trial). Trials. 2022;23(1):2.

Taneja S, Chowdhury R, Dhabhai N, Mazumder S, Upadhyay RP, Sharma S, et al. Impact of an integrated nutrition, health, water sanitation and hygiene, psychosocial care and support intervention package delivered during the pre- and peri-conception period and/or during pregnancy and early childhood on linear growth of infants in the first two years of life, birth outcomes and nutritional status of mothers: study protocol of a factorial, individually randomized controlled trial in India. Trials. 2020;21(1):127.

Taneja S, Upadhyay RP, Chowdhury R, Kurpad AV, Bhardwaj H, Kumar T, et al. Impact of nutritional interventions among lactating mothers on the growth of their infants in the first 6 months of life: a randomized controlled trial in Delhi. India Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113(4):884–94.

Vanslambrouck K, de Kok B, Toe LC, De Cock N, Ouedraogo M, Dailey-Chwalibóg T, et al. Effect of balanced energy-protein supplementation during pregnancy and lactation on birth outcomes and infant growth in rural Burkina Faso: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e038393.

Jones L, de Kok B, Moore K, de Pee S, Bedford J, Vanslambrouck K, et al. Acceptability of 12 fortified balanced energy protein supplements - insights from Burkina Faso. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(1):e13067.

de Kok B, Argaw A, Hanley-Cook G, Toe LC, Ouédraogo M, Dailey-Chwalibóg T, et al. Fortified balanced energy-protein supplements increase nutrient adequacy without displacing food intake in pregnant women in rural Burkina Faso. J Nutr. 2021;151(12):3831–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxab289, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34494113/.

de Kok B, Moore K, Jones L, Vanslambrouck K, Toe LC, Ouédraogo M, et al. Home consumption of two fortified balanced energy protein supplements by pregnant women in Burkina Faso. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(3):e13134.

de Kok B, Toe LC, Hanley-Cook G, Argaw A, Ouédraogo M, Compaoré A, et al. Prenatal fortified balanced energy-protein supplementation and birth outcomes in rural Burkina Faso: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. PLoS Med. 2022;19(5):e1004002.

Baye E, Abate FW, Eglovitch M, Shiferie F, Olson IE, Shifraw T, et al. Effect of birthweight measurement quality improvement on low birthweight prevalence in rural Ethiopia. Popul Health Metrics. 2021;19(1):35.

Lee AC, Abate FW, Mullany LC, Baye E, Berhane YY, Derebe MM, et al. Enhancing nutrition and antenatal infection treatment (ENAT) study: protocol of a pragmatic clinical effectiveness study to improve birth outcomes in Ethiopia. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2022;6(1):e001327.

Lama TP, Khatry SK, Isanaka S, Moore K, Jones L, Bedford J, et al. Acceptability of 11 fortified balanced energy-protein supplements for pregnant women in Nepal. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;n/a(n/a):e13336.

Lama TP, Moore K, Isanaka S, Jones L, Bedford J, de Pee S, et al. Compliance with and acceptability of two fortified balanced energy protein supplements among pregnant women in rural Nepal. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;n/a(n/a):e13306.

de Onis M, Garza C, Victora CG, Onyango AW, Frongillo EA, Martines J. The WHO multicentre growth reference study: planning, study design, and methodology. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(1 Suppl):S15–26.

The MAL-ED study. A multinational and multidisciplinary approach to understand the relationship between enteric pathogens, malnutrition, gut physiology, physical growth, cognitive development, and immune responses in infants and children up to 2 years of age in resource-poor environments. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59 Suppl 4:S193–206.

Seidler AL, Hunter KE, Cheyne S, Ghersi D, Berlin JA, Askie L. A guide to prospective meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;367:l5342.

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Meta-analyses of aggregate data or individual participant data Meta-analyses (retrospectively and prospectively pooled analyses). Population health Methods. 2022. Available from: https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/meta-analyses-aggregate-data-or-individual-participant-data-meta-analyses-retrospectively-and. Cited 2022 Nov 21.

Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, Califf RM, Ide NC. The ClinicalTrials.gov results database — update and key issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):852–60.

Gargon E, Gurung B, Medley N, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, et al. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99111.

Nijagal MA, Wissig S, Stowell C, Olson E, Amer-Wahlin I, Bonsel G, et al. Standardized outcome measures for pregnancy and childbirth, an ICHOM proposal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):953.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

The WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Association between Administration of Systemic Corticosteroids and Mortality among Critically ill Patients with COVID-19: a Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1330–41.

Seidler AL, Hunter KE, Espinoza D, Mihrshahi S, Askie LM, Askie LM, et al. Quantifying the advantages of conducting a prospective meta-analysis (PMA): a case study of early childhood obesity prevention. Trials. 2021;22(1):78.

Askie LM, Brocklehurst P, Darlow BA, Finer N, Schmidt B, Tarnow-Mordi W, et al. NeOProM: neonatal oxygenation prospective Meta-analysis collaboration study protocol. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11(1):6.

Brown V, Moodie M, Sultana M, Hunter KE, Byrne R, Seidler AL, et al. Core outcome set for early intervention trials to prevent obesity in childhood (COS-EPOCH): agreement on “what” to measure. Int J Obes. 2022;46(10):1867–74.

Thevakumar A, Valayatham V, Bewley S. Defining obstetric terms: the need for gold standards. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(1):36–43.

Menard MK, Main EK, Currigan SM. Executive summary of the reVITALize initiative: standardizing obstetric data definitions. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jul;124(1):150–3.

COMET Initiative Home. Available from: https://www.comet-initiative.org/. Cited 2022 Nov 22.

Knight M, INOSS. The international network of obstetric survey systems (INOSS): benefits of multi-country studies of severe and uncommon maternal morbidities. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(2):127–31.

Myatt L, Redman CW, Staff AC, Hansson S, Wilson ML, Laivuori H, et al. Strategy for standardization of preeclampsia research study design. Hypertension. 2014;63(6):1293–301.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the members of each research team for the studies participating in this initiative.

Collaborators listed under Maternal BEP Studies Harmonization Initiative:

Grace J Chan (Boston Children’s Hospital), Mulatu M Derebe (Amhara Public Health Institute), Fred van Dyk, Luke C Mullany, Daniel Erchick (Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health), Michelle S Eglovitch, Chunling Lu, Krysten North, Ingrid E Olson (Brigham and Women’s Hospital), Nebiyou Fasil, Workagenehu T Kidane, Fisseha Shiferie, Tigest Shifraw, Fitsum Tsegaye, Sitota Tsegaye (Addis Continental Institute of Public Health), Sheila Isanaka (Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health), Rose Molina, Michele Stojanov, Blair Wylie, (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center), Amare W Tadesse (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Addis Continental Institute of Public Health), Lieven Huybregts (International Food Policy Research Institute), Laeticia C Toe, Alemayehu Argaw, Giles Hanley-Cook (Ghent University), Rupali Dewan, Pratima Mittal, Harish Chellani (Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital), Tsering P Lama (Nepal Nutrition Intervention Project-Sarlahi), Benazir Baloch (Aga Khan University), Mihaela A Ciulei (The Pennsylvania State University).

Funding

This work was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, investment grant number INV-022373.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

ADG, NB, PK, ACL, YS, JT, and PC led the design of the initiative. All authors contributed to the harmonization of variables. ADG, KG, and LT wrote the first manuscript draft and prepared the tables. Our Technical Advisory Group, Drs. Martha Mwangome, Wafaie Fawzi, Sant-Rayn Pasricha, Parul Christian, and Rajiv Bahl served as scientific advisors. MAC (collaborator) helped with formatting the manuscript and other preparations for submission. All authors provided critical revisions to the manuscript and approved the final draft. ADG acts as guarantor for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is describing our process of harmonizing variables that will be collected across multiple trials. As such, no Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board approval was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We have read and understood the BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth policy on declaration of interests. All authors have been funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. ACL received grants or contracts from NICHD and the WHO, received license to Biliruler Granted from BWH to Little Sparrows Technologies, consulting fee from WHO and Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, has a patent for Biliruler, participated in the Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board for PRIMES study at the University of California San Francisco. PC worked at the BMGF from 2015 to 2019 during which the BEP trials were funded. ADG, KG, NB, PK, ACL, YS, JT, ST, RC, BDK, CL, ND, JK, SK, AM, LT, RPU, and PC obtained support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to travel to Seattle in February 2020 to participate in the meeting for this initiative. JT participated on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board at University of North Carolina and University of California San Francisco on studies unrelated to this manuscript. JT was a non-profit board member, unpaid, for the Helen Keller International, which may use the results of these trials, depending on the results, in their programming. JT was a non-profit board member, unpaid, for the Health Volunteers Overseas that conducts work unrelated to the topic of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

Harmonized variables with definitions, rationale, and additional considerations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gernand, A.D., Gallagher, K., Bhandari, N. et al. Harmonization of maternal balanced energy-protein supplementation studies for individual participant data (IPD) meta-analyses – finding and creating similarities in variables and data collection. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 107 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05366-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05366-2