Abstract

Objective

To examine maternal, psychosocial, and pregnancy factors associated with breastfeeding for at least 6 months in those giving birth for the first time.

Methods

We performed a planned secondary analysis of an observational cohort study of 5249 women giving birth for the first time. Women were contacted at least 6 months after delivery and provided information regarding breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity. Maternal demographics, psychosocial measures, and delivery methods were compared by breastfeeding groups.

Results

4712 (89.8%) of the women breastfed at some point, with 2739 (58.2%) breastfeeding for at least 6 months. Of those who breastfed, 1161 (24.7% of the entire cohort), breastfed exclusively for at least 6 months. In the multivariable model among those who ever breastfed, not smoking in the month prior to delivery (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.04, 95%CI 1.19–3.45), having a Master’s degree of higher (aOR 1.89, 95%CI 1.51–2.36), having a planned pregnancy (aOR 1.48, 95%CI 1.27–1.73), older age (aOR 1.02, 95% CI, 1.01–1.04), lower BMI (aOR 0.96 95% CI 0.95–0.97), and having less anxiety measured during pregnancy (aOR 0.990, 95%CI 0.983–0.998) were associated with breastfeeding for at least 6 months. Compared to non-Hispanic White women, Hispanic women, while being more likely to breastfeed initially (aOR 1.40, 95%CI 1.02–1.92), were less likely to breastfeed for 6 months (aOR 0.72, 95%CI 0.59–0.88). While non-Hispanic Black women were less likely than non-Hispanic White women to initiate breastfeeding (aOR 0.68, 95%CI 0.51–0.90), the odds of non-Hispanic Black women of continuing to breastfeed for at least 6 months was similar to non-Hispanic White women (aOR 0.92, 95%CI 0.71–1.19).

Conclusions

In this cohort of women giving birth for the first time, duration of breastfeeding was associated with several characteristics which highlight groups at greater risk of not breastfeeding as long as currently recommended.

Trial registration

NCT01322529 (nuMoM2b) and NCT02231398 (nuMoM2b-Heart Health)

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

The longer a woman breastfeeds her infant, the greater the benefits for both her own and her child’s health. Breastfed infants have decreased risk of infections, including gastrointestinal diseases, sepsis, wheezing respiratory tract infections, necrotizing enterocolitis, meningitis, and urinary tract infections [1,2,3,4]. Duration of being breastfed also is positively associated with intelligence later in life [5], as well as decreased prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [6,7,8,9]. Indeed, excess deaths of women due to myocardial infarction, breast cancer, and diabetes have been attributed to lack of or a shorter duration of breastfeeding [10].

So powerful are the overall health benefits of breastfeeding that the World Health Organization’s fifth Global Nutrition Target for 2025 is to increase the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months to at least 50% of all mothers [11]. As of 2017, however, only 25.6% of US women were exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months, with only 58.3% doing any breastfeeding at 6 months [12]. Previous successful breastfeeding is a factor strongly associated with duration of breastfeeding for a subsequent child [13, 14]. However, for women giving birth for the first time who have not had the opportunity to breastfeed previously, it is important to determine other factors associated with breastfeeding duration to inform potentially effective interventions that could be used to improve that rate. Prior reviews found that not smoking, having a vaginal delivery, high maternal educational attainment, and specific breastfeeding education were associated with higher rates of breastfeeding continuation [13]. These factors might inform multilevel strategies to optimize conditions so that all individuals who wanted to breastfeed would be able to breastfeed for as long as they desired. Additionally, there is a gap in the literature as most previous work on breastfeeding duration did not include validated psychosocial measures as covariates. As much of the previous work is not generalizable to US populations, and given demographic trends in the United States, contemporary understanding of these factors in a large representative diverse cohort is needed.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine maternal (both demographic and psychosocial) and pregnancy factors associated with breastfeeding for at least 6 months in a cohort of women giving birth for the first time.

Methods

Participants and measures

This study was a planned secondary analysis of a large prospective cohort study in women pregnant with their first child. The “Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: monitoring mothers-to-be” (nuMoM2b) project recruited 10,038 nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies from eight U.S. medical centers between 2010 and 2013 with the objective of identifying risk factors for and predictors of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Detailed methods of the nuMoM2b study are reported elsewhere [15]. The nuMoM2b Heart Health Study (HHS) followed 7003 women in the nuMoM2b cohort with interval contacts and an in-person study visit for cardiovascular health outcomes [16, 17]. Interval contacts for HHS began in 2013 and have been ongoing since then. Both the nuMoM2b and HHS studies were approved by the local Institutional Review Boards at each site and all women provided informed consent. Both studies were registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01322529, NCT02231398).

In brief, women in the nuMoM2b cohort were recruited in the first trimester and had study visits in the 1st (Visit 1: gestational age 6 weeks 0 days to 13 weeks 6 days), 2nd (Visit 2: gestational age 16 weeks 0 days to 21 weeks 6 days), and late 2nd-early 3rd (Visit 3: gestational age 22 weeks 0 days to 29 weeks 6 days) trimesters, and at the time of delivery (Visit 4). During study visits, which were conducted in English or Spanish, multiple questionnaires and psychosocial instruments were completed and biological specimens were obtained [15]. Psychosocial factors evaluated included: depression (Edinburgh Perinatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Visit 3) [18], perceived stress (Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Visit 1) [19], social support (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, Visit 1) [20], perceived anxiety (Spielberger Trait Anxiety Subscale, Visit 1) [21], resilience (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, Visit 2) [22] and perceived pregnancy experience (Pregnancy Experience Scale (PES), Visit 3) [23]. Characteristics of the psychosocial measures in the overall cohort have been presented elsewhere [24, 25]. Race and ethnicity were self-reported and collected in standard categories as required by the Federal funding agency (https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards). After delivery, certified chart abstractors extracted delivery outcomes from the medical records. During the postpartum stay, the method of feeding the newborn at discharge (breastfeeding, formula feeding, or a combination of both) was also abstracted.

For the HHS, interviews were performed by telephone or email at 6-month intervals, beginning at least 6 months after delivery of the index pregnancy. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish. During interviews, women updated contact information and answered questionnaires regarding any subsequent pregnancies, medications, medical conditions, cardiovascular events or diagnoses, and the health of their child. In addition, during the first interview, they answered questions about how their child was fed since delivery (Supplementary file 1). Specifically, women were asked if they ever breastfed their baby. If they responded “yes”, they were further asked how long their child was exclusively fed breast milk (“Was there a period of time when you fed this baby only breast milk (no formula, milk, juice, or food)? This is called exclusive breastfeeding.”), and how old the infant was when exclusive (“About how old was this baby when exclusive breastfeeding stopped?”) and non-exclusive breastfeeding (“About how old was this baby when all breastfeeding stopped?”) were discontinued [17]. Discontinuation options included: “Less than 6 weeks”; “6 weeks to 11 weeks”; “3–6 months”; “More than 6 months”; “Still breastfeeding”; and “Don’t know.” Women were considered to be breastfeeding for at least 6 months if they responded, “More than 6 months” or “Still breastfeeding.” The questions on breastfeeding were only asked at the first interval contact and were self-reported.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe participant characteristics and psychosocial scales according to whether women claimed ever breastfeeding, breastfeeding for at least 6 months, and exclusively breastfeeding for at least 6 months. Due to the response options being in the categories listed above, breastfeeding duration was not analyzed as a continuous variable. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using a Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, the Wilcoxon-rank sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and the chi-square test for categorical variables.

Multivariable logistic regression was then performed for the outcome of ever breastfeeding and the two conditional outcomes of any breastfeeding for at least 6 months and exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months. We included variables in the model that were significantly different (p < 0.05) for each outcome in the univariate analysis. Characteristics present in < 1% of the cohort were excluded from the regression. All analyses were conducted in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Overall cohort

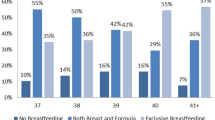

Of the original 10,038 nuMoM2b participants, 8838 were eligible for contacting in the HHS. Of those women, 7003 (79.2%) women were successfully contacted for HHS, with 5249 (74.9%) of them having complete data for all questions and making up the analytic cohort for this study. Characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1. A total of 4712 (89.8%) women claimed to have breastfed their infant at some point. Women who ever breastfed tended to be older, with lower BMI, and were more often non-Hispanic White, higher earning category, and had higher educational attainment (all p < 0.001). Additionally, women who ever breastfed were more likely to state that the pregnancy was planned (67.7% vs 41.3%, p < 0.001) and were less likely to have smoked in the month prior to delivery (1.9% vs 10.4%, p < 0.001). Women who delivered vaginally were statistically more likely to breastfeed their infants than women delivered by cesarean, although the absolute difference was small (90.3% vs 88.2%, p = 0.02).

Of the women who ever breastfed, 2739 (58.2%) continued breastfeeding for at least 6 months, with 1161 (24.7%) doing so exclusively. The same sociodemographic characteristics and directionality that were associated with “ever breastfeeding” above were also associated with “any breastfeeding for at least 6 months” among women who ever breastfed. Exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months was associated with older age, lower BMI, having higher income, having higher educational attainment, and not smoking (Table 2).

Psychosocial associations

Psychosocial measures were also significantly different between women in different breastfeeding categories (Table 2). In general, women who had lower depression scores, higher social support scores, higher resiliency scores, lower anxiety measures, and lower perceived stress scores breastfed longer. The median scores for the pregnancy experiences hassle intensity ratio were lower for women who breastfed longer.

Psychosocial measures noted above which were associated with ever breastfeeding, breastfeeding for at least 6 months, or exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months individually (Table 2) were found not to be statistically significant when included in a logistic regression model together. As the psychosocial measures were found to have significant collinearity with one another (Pearson correlation coefficients available in Appendix), we included each in the logistic regression model one at a time and selected the measure most highly associated with the outcome to include in the final model. Given the strong association of the psychosocial measures with each other (Table 4 in Appendix), the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory measure was selected to be included in the final regression model as it demonstrated the strongest association with the outcome.

Logistic regression for associations with breastfeeding and duration

The final logistic regression (Table 3) demonstrated that women had higher odds of ever breastfeeding if they were Hispanic women (compared with non-Hispanic White women) (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.02–1.92), had higher incomes (compared to < 100% of FPL- OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.12–2.27 for > 200% of FPL; OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.03–2.10 for 100–200% of FPL), higher educational attainment (compared to high school or less- OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.90–4.14 for Master’s degree or higher; OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.62–2.76 for bachelor degree or less), and had not smoked in the month prior to delivery (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.56–3.45). Compared with non-Hispanic White women, non-Hispanic Black women had lower odds of breastfeeding their infant (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.51–0.91), as did women with higher BMI (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.94–0.97), and higher anxiety (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.56–3.45 for each point increase on the scale).

For women who breastfed, the odds of any breastfeeding for at least 6 months increased as maternal age increased (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.04 for each year), while the odds of any breastfeeding for at least 6 months decreased with increasing BMI (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.95–0.97, for each kg/m2, Table 3). Compared with non-Hispanic White women, Hispanic women who initially breastfed were less likely to breastfeed for at least 6 months (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.59–0.89). Those with higher educational attainment, compared to those women completing high school or less, were more likely to breastfeed for at least 6 months (compared to high school or less- OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.51–2.36 for Master’s degree or higher; OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.20–1.70 for bachelor degree or less), as were those women who stated that the pregnancy was planned (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.27–1.73). Women who did not smoke in the month prior to delivery were more likely to breastfeed for at least 6 months (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.19–3.45). Women with higher anxiety scores were less likely to breastfeed for at least 6 months (OR 0.990, 95% CI 0.983–0.998 for each point increase on the scale).

Older age (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05), not smoking the month prior to delivery (OR 3.12, 95% CI 1.43–7.14), and being at 100–200% of the federal poverty level (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.08–2.13) all were associated with higher odds of exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months. Increasing BMI was associated with lower odds of exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96–0.99).

Discussion

For women giving birth for the first time in a large and racially and ethnically diverse U.S. cohort, 89.8% breastfed their infant, with 58.2% breastfeeding for at least 6 months. Being older, having a lower BMI, not smoking in the month prior to delivery, and being at 100–200% of the federal poverty level (compared to those at < 100%) were associated with higher odds of exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months. While rates of breastfeeding and breastfeeding for at least 6 months differed across some racial and ethnic groups, the groups did not have significantly different odds of exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months.

Our findings are consistent with other reports noting that age and weight are associated with breastfeeding duration [26, 27]. We also found that women who smoked proximate to delivery were less likely to breastfeed. This finding was also noted among individuals in a Spanish birth cohort, in whom smoking was associated with a more than two-fold higher rate of formula feeding and shorter breastfeeding duration [28]. Previous studies found that other social markers (such as lower education attainment and not attending prenatal classes), as well as physiologic factors such as delayed onset of lactation, inadequate milk production, nipple pain, latching problems and lack of social support are associated with early discontinuation of breastfeeding [29, 30]. Attending prenatal classes and a previous successful breastfeeding experience have been associated with longer duration of breastfeeding [11, 30].

We found that Hispanic women were more likely to initiate breastfeeding, but that these women were less likely to breastfeed for at least 6 months. This has also been noted in a few other studies [31,32,33]. Level of acculturation and whether women speak primarily English or Spanish may impact breastfeeding duration in Hispanic women [33, 34]. Spanish-speaking women may represent a group who could benefit from culturally-sensitive, family-level interventions and work place policies to increase breastfeeding duration [33, 35]. While non-Hispanic Black women giving birth for the first time in the cohort had lower odds of initiating breastfeeding, those who did breastfeed had similar odds of exclusively breastfeeding for at least 6 months. Thus, improved initial uptake of breastfeeding for non-Hispanic Black mothers is important.

Multiple reports have addressed some aspects of the relationship of maternal psychosocial measures and mental health on breastfeeding duration. As in our cohort, other smaller cohorts noted that higher anxiety scores are independently associated with shorter breastfeeding duration [36,37,38,39]. Social support was also positively associated with breastfeeding duration [27]. Other studies that found a negative association of depression and breastfeeding highlighted the importance of a pre-pregnancy diagnosis of depression [40]. In the current cohort, a history of mental health disorders was not significantly associated with breastfeeding duration. Only a history of bipolar disorder was associated with lower rates of breastfeeding, but with so few women endorsing that history (n = 79), these findings should be interpreted with caution as it was not included in the regression model.

Breastfeeding benefits are numerous for both the mother and infant. Benefits to women who breastfeed include increased caloric expenditure in the postpartum period and lower risks for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and breast cancer [2, 6, 9]. Breastfed infants have decreased long-term risks of childhood cancers and many other positive health benefits [41,42,43]. Formula costs approximately $1200–$1500 USD per year per infant which places extra financial burden on parents and community resources [44]. These individual medical and nonmedical benefits translate into significant population-level benefits given the nearly 4 million births that occur yearly in the US [10, 45].

Investigators and health agencies have called for identifying modifiable factors that can be targeted to help improve breastfeeding duration. The need for improvements is underscored by the findings in the current study: the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months (24.7%) was well below the 2025 WHO goal of 50% [11]. The findings in our population are slightly lower than other published rates in the US [12]. This may be because our population only included women giving birth for the first time. Educational campaigns and community-level support have been proposed to help improve breastfeeding rates, particularly among underserved populations [11, 46]. Identifying the women most at risk for not initiating any breastfeeding may be an important approach to help target intervention strategies as well. A comprehensive approach of support includes not only education and engagement, but also policies that foster and protect a woman’s right, choice, and opportunity to breastfeed [11, 47, 48].

Our study was limited in that we did not ask women for a specific date or number of weeks that they breastfed. The first interval contact was no earlier than 6 months after delivery, allowing for women who had breastfed for at least 6 months to note that outcome. As we asked the women to answer the question after breastfeeding may have stopped, it is possible that their responses may have been affected by recall or social-desirability bias. Yet, it has been shown that most women have accurate recall of duration of breastfeeding their first baby [49, 50], and accordingly we do not believe this type of bias is likely to influence our results systematically. We also did not ask participants when they returned to work, which may influence breastfeeding longevity [51, 52]. We also did not address other reasons for discontinuation, such as perception of milk supply, in the current study. We were unable to collect information on contraception or other medications being used in the postpartum timeframe. As a multicenter, diverse cohort, our findings are generalizable to similar populations of individuals giving birth for the first time.

Designing multilevel public health strategies and policies to help optimize prepregnancy health and education regarding breastfeeding, along with support in the early postpartum period, may help improve the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months in order to reach the 2025 Global Nutrition Target of at least 50% of mothers. These programs may include smoking cessation programs, more frequent contact with lactation specialists in the early postpartum period, community-based peer support for women in at-risk racial groups or with high anxiety, and effective workplace policies to support breastfeeding for women returning to work [53,54,55,56]. Supporting women who begin breastfeeding but who may stop before 6 months could be a particular area of focus, particularly for Hispanic women as seen in this cohort. These strategies and interventions, which help to ensure women who want to breastfeed are able to continue, should be tested in prospective cohorts as the benefits of breastfeeding extend to the infant, the mother, and society.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this cohort of women giving birth for the first time, exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months was associated with older age, lower BMI, and not smoking in the month before delivery.

Availability of data and materials

Data from nuMoM2b used for this analysis are available in the NICHD DASH repository (https://dash.nichd.nih.gov/). The data on breastfeeding longevity from the nuMoM2b-HHS are not yet publicly available. Requests for these data will be considered by the Data Coordinating Center, Research Triangle International. Contact corresponding author for details.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CD-RISC:

-

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Perinatal Depression Scale

- FPL:

-

Federal poverty level

- HHS:

-

Heart Health Study

- MSS:

-

Multidimension perceived social support scale

- NICHD DASH:

-

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Data and Specimen Hub

- nuMoM2b:

-

Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: monitoring mothers-to-be

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PES:

-

Pregnancy Experiences Scale

- PSS:

-

Perceived Stress Scale

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- STAI-T:

-

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- USD:

-

United States dollars

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen-Rivers LA. Differences in morbidity between breast-fed and formula-fed infants. J Pediatr. 1995;126(5 Pt 1):696–702.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, Franca GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90.

Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Martinez FD, Morgan WJ, Taussig LM. Breast feeding and lower respiratory tract illness in the first year of life. Group Health Medical Associates. BMJ. 1989;299(6705):946–9.

Schanler RJ, Shulman RJ, Lau C. Feeding strategies for premature infants: beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human milk versus preterm formula. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6 Pt 1):1150–7.

Mortensen EL, Michaelsen KF, Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. The association between duration of breastfeeding and adult intelligence. JAMA. 2002;287(18):2365–71.

Schwarz EB, Ray RM, Stuebe AM, Allison MA, Ness RB, Freiberg MS, et al. Duration of lactation and risk factors for maternal cardiovascular disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(5):974–82.

Ajmera VH, Terrault NA, VanWagner LB, Sarkar M, Lewis CE, Carr JJ, et al. Longer lactation duration is associated with decreased prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in women. J Hepatol. 2019;70(1):126–32.

Gunderson EP, Jacobs DR Jr, Chiang V, Lewis CE, Feng J, Quesenberry CP Jr, et al. Duration of lactation and incidence of the metabolic syndrome in women of reproductive age according to gestational diabetes mellitus status: a 20-year prospective study in CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults). Diabetes. 2010;59(2):495–504.

Gunderson EP, Lewis CE, Lin Y, Sorel M, Gross M, Sidney S, et al. Lactation duration and progression to diabetes in women across the childbearing years: the 30-year CARDIA study. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):328–37.

Bartick MC, Schwarz EB, Green BD, Jegier BJ, Reinhold AG, Colaizy TT, et al. Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(1):e12366.

WHO/UNICEF. Global nutrition targets 2025: breastfeeding policy brief (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.7). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Breastfeeding among U.S. children born 2010–2017, CDC national immunization survey. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/results.html. Accessed 31 Mar 2021.

Cohen SS, Alexander DD, Krebs NF, Young BE, Cabana MD, Erdmann P, et al. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;203:190–196.e121.

Sutherland T, Pierce CB, Blomquist JL, Handa VL. Breastfeeding practices among first-time mothers and across multiple pregnancies. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(8):1665–71.

Haas DM, Parker CB, Wing DA, Parry S, Grobman WA, Mercer BM, et al. A description of the methods of the nulliparous pregnancy outcomes study: monitoring mothers-to-be (nuMoM2b). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(4):539.e531–24.

Haas DM, Parker CB, Marsh DJ, Grobman WA, Ehrenthal DB, Greenland P, et al. Association of adverse pregnancy outcomes with hypertension 2 to 7 years postpartum. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(19):e013092.

Haas DM, Ehrenthal DB, Koch MA, Catov JM, Barnes SE, Facco F, et al. Pregnancy as a window to future cardiovascular health: design and implementation of the nuMoM2b heart health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(6):519–30.

Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord. 1996;39(3):185–9.

Cole SR. Assessment of differential item functioning in the perceived stress scale-10. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(5):319–20.

Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7.

Spielberger CD. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82.

DiPietro JA, Christensen AL, Costigan KA. The pregnancy experience scale-brief version. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;29(4):262–7.

Bann CM, Parker CB, Grobman WA, Willinger M, Simhan HN, Wing DA, et al. Psychometric properties of stress and anxiety measures among nulliparous women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(1):53–62.

Grobman WA, Parker C, Wadhwa PD, Willinger M, Simhan H, Silver B, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in measures of self-reported psychosocial states and traits during pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33(14):1426–32.

Blyth RJ, Creedy DK, Dennis CL, Moyle W, Pratt J, De Vries SM, et al. Breastfeeding duration in an Australian population: the influence of modifiable antenatal factors. J Hum Lact. 2004;20(1):30–8.

Meedya S, Fahy K, Kable A. Factors that positively influence breastfeeding duration to 6 months: a literature review. Women Birth. 2010;23(4):135–45.

Lechosa Muniz C, Paz-Zulueta M, Del Rio EC, Sota SM, Saez de Adana M, Perez MM, et al. Impact of maternal smoking on the onset of breastfeeding versus formula feeding: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):04.

Yilmaz E, Doga Ocal F, Vural Yilmaz Z, Ceyhan M, Kara OF, Kucukozkan T. Early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding: factors influencing the attitudes of mothers who gave birth in a baby-friendly hospital. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;14(1):1–9.

Garbarino F, Morniroli D, Ghirardi B, Garavaglia E, Bracco B, Gianni ML, et al. Prevalence and duration of breastfeeding during the first six months of life: factors affecting an early cessation. Pediatr Med Chir. 2013;35(5):217–22.

Sloand E, Budhathoki C, Junn J, Vo D, Lowe V, Pennington A. Breastfeeding among Latino families in an urban pediatric office setting. Nurs Res Pract. 2016;2016:9278401.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state - National Immunization Survey, United States, 2004-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(11):327–34.

Ahluwalia IB, D’Angelo D, Morrow B, McDonald JA. Association between acculturation and breastfeeding among Hispanic women: data from the pregnancy risk assessment and monitoring system. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(2):167–73.

McKinney CO, Hahn-Holbrook J, Chase-Lansdale PL, Ramey SL, Krohn J, Reed-Vance M, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20152388.

Hohl S, Thompson B, Escareño M, Duggan C. Cultural norms in conflict: breastfeeding among Hispanic immigrants in rural Washington state. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(7):1549–57.

Grigoriadis S, Graves L, Peer M, Mamisashvili L, Tomlinson G, Vigod SN, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antenatal anxiety on postpartum outcomes. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2019;22(5):543–56.

Horsley K, Nguyen TV, Ditto B, Da Costa D. The association between pregnancy-specific anxiety and exclusive breastfeeding status early in the postpartum period. J Hum Lact. 2019;35(4):729–36.

Shay M, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Tough S. Maternal psychological distress and child weight at 24 months: investigating indirect effects through breastfeeding in the all our families cohort. Can J Public Health. 2020;111(4):543–54.

Stuebe AM, Meltzer-Brody S, Propper C, Pearson B, Beiler P, Elam M, et al. The mood, mother, and infant study: associations between maternal mood in pregnancy and breastfeeding outcome. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14(8):551–9.

Wallenborn JT, Joseph A-C, Graves WC, Masho SW. Prepregnancy depression and breastfeeding duration: a look at maternal age. J Pregnancy. 2018;2018:7.

Kwan ML, Buffler PA, Abrams B, Kiley VA. Breastfeeding and the risk of childhood leukemia: a meta-analysis. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(6):521–35.

Dee DL, Li R, Lee LC, Grummer-Strawn LM. Associations between breastfeeding practices and young children's language and motor skill development. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 1):S92–8.

Yamakawa M, Yorifuji T, Kato T, Inoue S, Tokinobu A, Tsuda T, et al. Long-term effects of breastfeeding on children’s hospitalization for respiratory tract infections and diarrhea in early childhood in Japan. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(9):1956–65.

Breastfeeding: surgeon general’s call to action fact sheet. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/breastfeeding/factsheet/index.html. Accessed 31 Mar 2021.

Bartick MC, Stuebe AM, Schwarz EB, Luongo C, Reinhold AG, Foster EM. Cost analysis of maternal disease associated with suboptimal breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(1):111–9.

Mitra AK, Khoury AJ, Hinton AW, Carothers C. Predictors of breastfeeding intention among low-income women. Matern Child Health J. 2004;8(2):65–70.

ACOG. Committee Opinion No. 756: optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(4):e187–96.

Perrine CG, Galuska DA, Dohack JL, Shealy KR, Murphy PE, Mlis, et al. Vital signs: improvements in maternity care policies and practices that support breastfeeding - United States, 2007-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(39):1112–7.

Amissah EA, Kancherla V, Ko YA, Li R. Validation study of maternal recall on breastfeeding duration 6 years after childbirth. J Hum Lact. 2017;33(2):390–400.

Natland ST, Andersen LF, Nilsen TIL, Forsmo S, Jacobsen GW. Maternal recall of breastfeeding duration twenty years after delivery. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:179.

Brown CR, Dodds L, Legge A, Bryanton J, Semenic S. Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Can J Public Health. 2014;105(3):e179–85.

Dutheil F, Méchin G, Vorilhon P, Benson AC, Bottet A, Clinchamps M, et al. Breastfeeding after returning to work: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8631.

Johnson A, Kirk R, Rosenblum KL, Muzik M. Enhancing breastfeeding rates among African American women: a systematic review of current psychosocial interventions. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(1):45–62.

Patel S, Patel S. The effectiveness of lactation consultants and lactation counselors on breastfeeding outcomes. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(3):530–41.

Asiodu IV, Bugg K, Palmquist AEL. Achieving breastfeeding equity and justice in black communities: past, present, and future. Breastfeed Med. 2021;16(6):447–51.

Segura-Pérez S, Hromi-Fiedler A, Adnew M, Nyhan K, Pérez-Escamilla R. Impact of breastfeeding interventions among United States minority women on breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):72.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge Tondy Baumgartner, MD, MSEd1, Surya Sruthi Bhamidipalli, MPH1, David Guise, MSc, MPH1, Joanne Daggy, PhD1 for their contributions to the analysis and paper.

Funding

This study was supported by grant funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD): U10 HD063036, RTI International; U10 HD063072, Case Western Reserve University; U10 HD063047, Columbia University; U10 HD063037, Indiana University; U10 HD063041, University of Pittsburgh; U10 HD063020, Northwestern University; U10 HD063046, University of California Irvine; U10 HD063048, University of Pennsylvania; and U10 HD063053, University of Utah. This study was also supported by funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI): U10-HL119991, RTI International; U10-HL119989, Case Western Reserve University; U10-HL120034, Columbia University; U10-HL119990, Indiana University; U10-HL120006, University of Pittsburgh; U10-HL119992, Northwestern University; U10-HL120019, University of California Irvine; U10-HL119993, University of Pennsylvania; and U10-HL120018, University of Utah. In addition, support was provided by respective Clinical and Translational Science Institutes to Indiana University (UL1TR001108) and University of California Irvine (UL1TR000153). This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. As a cooperative agreement funding mechanism, the NICDH Program Officer was involved in the design of the study but not in the performing of the study, collection of data, or this analysis. NIH employees who are authors on this manuscript were not involved in the primary writing but were involved in the final editing and do satisfy authorship requirements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors (DH, ZY, CP, JC, SP, WG, BM, HS, RS, RW, GS, PG, NBM, UR, VP) contributed to the study design, implementation, analysis, and manuscript preparation. All approve of this final submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Both the nuMoM2b and HHS studies were approved by the local Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at each site and all women provided written informed consent. These were IRBs at: RTI International (Research Triangle IRB); Case Western Reserve University (Case Western Reserve University IRB); Columbia University (Columbia University IRB); Indiana University (Indiana University/IUH IRB); University of Pittsburgh (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center IRB); Northwestern University (Northwestern University IRB); University of California Irvine (UC Irvine IRB); University of Pennsylvania (University of Pennsylvania IRB); and University of Utah (University of Utah IRB). Both studies were registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01322529, NCT02231398).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests related to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Interval contact form. This is one of the pages of the Interval Contact Form used for contacting participants in the nuMoM2b-HHS that asked about feeding of the infant after birth.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Haas, D.M., Yang, Z., Parker, C.B. et al. Factors associated with duration of breastfeeding in women giving birth for the first time. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 722 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05038-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05038-7