Abstract

Background

Prenatal posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is often overlooked in obstetric care, despite evidence that untreated PTSD negatively impacts both mother and baby. OB-GYN clinics commonly screen for depression in pregnant patients; however, prenatal PTSD screening is rare. Although the lack of PTSD screening likely leaves a significant portion of pregnant patients with unaddressed mental health needs, the size of this care gap has not been previously investigated.

Methods

This retrospective chart review study included data from 1,402 adult, pregnant patients who completed PTSD (PTSD Checklist-2; PCL) and depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Survey; EPDS) screenings during a routine prenatal care visit. Descriptive statistics identified screening rates for PTSD and depression, and logistic regression analyses identified demographic variables associated with screening outcomes and assessed whether screening results (+ PCL/ + EPDS, + PCL/-EPDS, -PCL/ + EPDS, -PCL/-EPDS) were associated with different provider intervention recommendations.

Results

11.1% of participants screened positive for PTSD alone, 3.8% for depression alone, and 5.4% for both depression and PTSD. Black (OR = 2.24, 95% CI [1.41,3.54]) and Latinx (OR = 1.64, 95% CI [1.01,2.66]) patients were more likely to screen positive for PTSD compared to White patients, while those on public insurance were 1.64 times (95% CI [1.21,2.22]) more likely to screen positive compared to those with private insurance. Patients who screened positive for both depression and PTSD were most likely to receive referrals for behavioral health services (44.6%), followed by -PCL/ + EPDS (32.6%), + PCL/-EPDS (10.5%), and -PCL/-EPDS (3.6%). A similar pattern emerged for psychotropic medication prescriptions.

Conclusions

Over ten percent of pregnant patients in the current study screened positive for PTSD without depression, highlighting a critical mental health need left unaddressed by current obstetric standards of care. Routine PTSD screening during prenatal care alongside strategies aimed at increasing referral resources and access to mental health services are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prenatal posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a significant pregnancy complication affecting millions of individuals worldwide each year. Epidemiological studies reveal PTSD prevalence rates ranging from 3.3 to 19.0% among pregnant people, with rates varying widely depending on sample characteristics such as trauma exposure and medical/psychiatric risk [1]. Left untreated or inadequately treated, prenatal PTSD can impart long-lasting consequences on families – pregnant patients with PTSD are at higher risk for pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes (e.g., preeclampsia, low birthweight, preterm birth) which have negative, downstream impacts on infant development [2,3,4,5,6].

Perinatal depression screening is recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and required by law in some U.S. jurisdictions [7, 8]. However, PTSD symptoms rarely receive similar attention [9], leaving an unknown number of pregnant individuals whose condition may require different or additional treatment. To better understand the extent of this healthcare gap, the current study investigated PTSD and depression screening rates among pregnant patients presenting for prenatal care at a hospital-based obstetrics and gynecology (OB-GYN) clinic.

Methods

Participants and procedure

In 2019, our prenatal clinics added PTSD screening to the standard depression screening conducted during initial prenatal care visits. This retrospective chart review included electronic medical record data spanning 9 months from 1,402 pregnant, adult patients who completed both PTSD and depression screenings during their prenatal visit (see Table 1 for sample characteristics). In addition to screening data, we also extracted demographic information, psychotropic medications prescribed, and referrals to psychology, psychiatry, and social work within one month of screening. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) designated the study exempt.

Measures

Clinic staff administered the PTSD Checklist-2 (PCL-2; [10]) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screening (EPDS; [11]) to screen for PTSD and depression symptoms, respectively. The PCL-2 is a two-item screening questionnaire derived from the 17-item PTSD Checklist-Civilian version (PCL-C; [12]), which assesses the frequency of PTSD symptoms within the past month. Prior validation work has demonstrated that the PCL-2 is a reliable and valid screening instrument in the primary care setting, performing on par with the PCL-C [10]. The 10-item EPDS is a commonly-used screening tool for depression in postnatal and antenatal settings [13]. The self-report measures used in this study were not under license.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Using descriptive statistics and logistic regression, we examined screening rates for PTSD and depression and tested whether race/ethnicity and insurance status were associated with different screening results. Logistic regression models also assessed whether screening results (+ PCL/ + EPDS, + PCL/-EPDS, -PCL/ + EPDS, -PCL/-EPDS) were associated with differences in medication prescriptions and provider referrals for behavioral/mental health services (i.e., psychology, psychiatry, or social work).

Results

PTSD and depression screening results

Fully 16.7% (n = 234) of pregnant patients screened positive for PTSD and 9.2% (n = 111) screened positive for depression. A total of 11.1% (n = 133) screened positive for PTSD alone, 3.8% (n = 46) for depression alone, and 5.4% (n = 65) for both depression and PTSD.

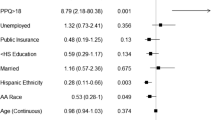

Logistic regression analyses revealed that pregnant patients’ racial/ethnic identities were significantly associated with PTSD (χ2 (3, N = 1,373) = 17.05, p = 0.001) and depression (χ2 (3, N = 1,181) = 9.46, p = 0.024) screening results (see Table 2). Black patients (20.3%; OR = 2.24, 95% CI [1.41,3.54]) and Latinx patients (15.7%; OR = 1.64, 95% CI [1.01,2.66]) were more likely to screen positive for PTSD compared to White patients (10.3%), while Asian patients did not have significantly different screening rates (9.1%; OR = 0.88, 95% CI [0.38, 2.02]) compared to White patients. With respect to depression, Black patients (11.0%; OR = 2.51, 95% CI [1.26,5.02]) and Latinx patients (9.6%; OR = 2.17, 95% CI [1.06,4.45]) were more likely to screen positive compared to White patients (4.7%), while Asian patients’ depression screening results (4.2%, OR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.24, 3.37]) did not differ significantly from White patients’ results.

Insurance coverage was also significantly associated with PTSD (χ2 (1, N = 1,375) = 10.10, p = 0.002) and depression (χ2 (1, N = 1,183) = 11.52, p = 0.001) screening results (see Table 2). Pregnant patients with public insurance were more likely to screen positive for PTSD (19.1%; OR = 1.64, 95% CI [1.21,2.22]) and depression (11.5%; OR = 2.14, 95% CI [1.37,3.34]) compared to those with private insurance (12.6% PTSD positive; 5.7% depression positive).

Relationships between screening results and provider recommendations

Participants’ screening results were associated with the likelihood that they received a referral for behavioral health services (χ2 (3, N = 1,203) = 190.76, p < 0.0001; see Table 3). Pregnant patients in the PCL-/EPDS + group were 4.11 times (32.6%; 95% CI [1.80,9.42]) more likely receive a referral compared to the PCL + /EPDS- group (10.5%). However, the PCL + /EPDS- group was more likely (OR = 3.20, 95% CI [1.67,6.14]) to receive behavioral health referrals compared to the PCL-/EPDS- group (3.6%).

Screening results were also significantly associated with the likelihood that pregnant patients were prescribed a psychotropic medication within one month of their visit (χ2 (3, N = 1,203) = 16.93, p = 0.001; see Table 3). Individuals in the PCL + /EPDS- (16.5%) were no more likely to be prescribed a medication compared to the PCL-/EPDS- group (15.3%; OR = 1.09, 95% CI [0.67,1.79]. There was a marginal difference between the PTSD alone group and the depression alone group, such that the PCL-/EPDS + group (28.3%) was 1.99 times (95% CI [0.90,4.37]) more likely to receive a prescription compared to the PCL + /EPDS- group.

Discussion

Almost 17% of pregnant patients in the current study screened positive for PTSD during a routine prenatal care visit. Patients were more than twice as likely to screen positive for clinically significant PTSD symptoms compared to depressive symptoms, and over ten percent of the sample screened positive for PTSD without depression. Results are consistent with prior research suggesting that up to 20% of trauma-exposed pregnant patients experience diagnosable PTSD [1], and suggest that a substantial number of pregnant patients do not get their mental health needs met by our current screening standards.

Black and Latinx patients had higher rates of both PTSD and depression compared to White patients. These findings parallel prior evidence that PTSD is more common among ethnic/racial minority patients during pregnancy and postpartum (e.g., [14, 15]). Individuals with public insurance also had higher rates of positive screens compared to those on private insurance, consistent with prior research finding that indicators of lower socioeconomic status (i.e., less educational attainment and income) are associated with greater PTSD risk during pregnancy [16]. Thus, by not screening for and addressing PTSD during pregnancy, we create a care gap that disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minority and low-income patients and leaves an intergenerational impact on families.

Untreated PTSD in pregnancy has been linked to several pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes, including preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, low birth weight, and preterm birth [2,3,4,5,6]. In part, these outcomes may be driven by health behaviors that frequently co-occur with PTSD, such as tobacco, alcohol and substance use, as well as underutilization of prenatal care [17]. However, when researchers account for the effects of health behaviors, PTSD nevertheless appears to disrupt the neuroendocrine system, dysregulating maternal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis) functioning linked with unfavorable pregnancy, childbirth, and infant outcomes [18,19,20,21]. Perhaps most critically, PTSD is closely linked with suicidal behavior and drug overdose, two leading causes of maternal death [22,23,24,25].

Left untreated, PTSD often persists into the postpartum period [16], producing further deleterious effects on mother, infant, and their burgeoning relationship. For example, evidence suggests that postpartum PTSD is associated with more negative maternal perceptions of their infant’s behavior [26, 27] and reduced parental sensitivity and responsiveness [28]. In offspring, perinatal PTSD has been linked to infant neuroendocrine dysregulation [20, 29] and impaired emotion regulation capacity [19, 26]. Thus, untreated prenatal PTSD has the potential to produce downstream consequences that ripple across generations.

Clinical implications

PTSD and depression involve overlapping symptoms (e.g., alterations in cognitions/mood; sleep disturbance) and are highly co-morbid [30]. Optimal treatment addresses the complete symptom constellation, but only when accurately identified. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a viable option for pregnant individuals with depression and are the most commonly prescribed class of psychotropic medications [31], but are not recommended as first-line treatment for PTSD according to the Veteran’s Administration and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, who instead recommend non-pharmacological interventions [32, 33]. Thus, to comprehensively address the mental health needs during pregnancy, sensitive screening measures that identify potential signs of depression and PTSD are warranted.

Our additional recommendations for implementing PTSD screening into routine OB-GYN care include: 1) universal screening for all OB-GYN patients, regardless of perceived risk, 2) use of brief, validated screening measures and 3) ongoing screening that extends into the postpartum period. Screening measures should be standardized and validated in pregnant samples, consistent with ACOG recommendations for depression screening [7]. The current study used the PCL-2, a 2-item version of the lengthier PCL-C. The PCL-C demonstrated excellent reliability and strong evidence of validity in a sample of over 3,000 pregnant women [34]. Another option is the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5; [35]), a 4-item measure developed for use in the primary care setting and validated in pregnant samples [9].

While screening during pregnancy is critical for early intervention and risk mitigation, there is also compelling meta-analytic evidence supporting continued screening in the postpartum period because there is small increase in PTSD prevalence rates from pregnancy to 4–6 weeks postpartum [1]. There are numerous potential causes for this phenomenon. The childbirth experience may exacerbate existing PTSD or interact with prior trauma to produce PTSD onset or recurrence. Alternatively, birth trauma may trigger new-onset PTSD among individuals without any prior trauma history. Indeed, a large prospective study of over 1,000 women demonstrated that nearly half the sample (45.5%) described their childbirth as traumatic in the first month postpartum [36]. By 3 months postpartum, 6.3% of the sample met criteria for PTSD. Additionally, 3% of the sample reported no trauma exposure or PTSD symptoms during or prior to pregnancy but went on to develop PTSD by 3 months postpartum following traumatic childbirth. Thus, similar to current recommendations for depression screening, PTSD screening should be extended across all stages of pregnancy and postpartum.

Even with attention to PTSD screening, pregnant patients who screened positive only for PTSD were less likely to receive a behavioral health referral or psychotropic medication prescription compared to individuals who screened positive for depression alone, suggesting that treatment access was more restricted for PTSD compared to depression. The reasons for this are likely multifactorial and occur at the patient, provider, organization, and health system levels. Prior research suggests that OB-GYN providers feel under-trained and unprepared to assess patients’ trauma histories and intervene effectively [37]. Providers also report limited access to non-pharmacological treatment options for patients who endorse mental health concerns [38]. In addition to challenges on the provider side, patients with PTSD report reduced self-efficacy in communication with their perinatal care providers [39], and may be less likely to report mental health concerns compared to patients without a history of trauma and/or PTSD.

System-level barriers also prevent effective mental health screening in obstetrics and perinatal care. Lessons learned from perinatal depression screening initiatives have clearly shown that impact is diminished unless screening is combined with comprehensive and ongoing mental health training for all staff, adequate staff support, and integration of mental health into OB-GYN clinics using stepped-care or co-located care models [40]. Mental health screening absent staff, resources, and accessible intervention sets these initiatives up to fail, placing unrealistic demands on providers and staff to solve complex problems with inadequate resources. Policy and practice would benefit from a holistic or transdiagnostic approach that addresses patients’ mental health concerns and healthcare gaps in tandem. Such approaches may involve systems-level interventions, such as increased utilization of mental health extenders and digital mental health tools that are more widely accessible to patients and providers alike.

Thus, screening for PTSD in prenatal settings may improve mental health treatment, but screening must be coupled with appropriate training, referral resources, and adequate access to PTSD behavioral health services. Perinatal mental health concerns are complex and often overlooked relative to medical conditions in pregnancy despite conferring high risk for maternal and infant health outcomes. Provider, patient, and system-level interventions with adequate reimbursement are necessary to adequately address these mental health concerns during this sensitive period of life.

Limitations

The current study included electronic medical record data from a large, diverse sample of pregnant patients who completed screening measures as part of their routine prenatal care, thus enhancing ecological validity. However, PTSD prevalence rates varied depending on patient and contextual factors, and our reliance on retrospective chart review data precluded collection of participant information that may have shed more light on additional demographic (e.g., income, education level) and clinical characteristics (e.g., trauma exposure chronicity and type) that distinguish pregnant patients who screen positive for PTSD in obstetric clinic settings. Additionally, we were unable to assess whether participants had already established care with a psychiatrist or behavioral health specialist prior to their prenatal care visit; thus, provider referral data presented in this report may underestimate how often patients were able to connect to these services. Finally, data were not available to assess longitudinal maternal or infant outcomes. Future prospective work is needed to evaluate the long-term impact of prenatal PTSD screening on patients and families.

Conclusion

The current study identifies a missed opportunity in current obstetric care practice that could be remedied with routine, universal screening for PTSD during prenatal care. Further studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effects of PTSD screening implementation and identify multi-tiered access-to-care interventions that address additional barriers to connecting patients with mental health resources.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Survey

- OB-GYN:

-

Obstetrics and gynecology

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCL-2:

-

PTSD Checklist-2

- PTSD:

-

Posttraumatic stress disorder

References

Yildiz PD, Ayers S, Phillips L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;15(208):634–45.

Shaw JG, Asch SM, Kimerling R, Frayne SM, Shaw KA, Phibbs CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1111–9.

Shaw JG, Asch SM, Katon JG, Shaw KA, Kimerling R, Frayne SM, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and antepartum complications: a novel risk factor for gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2017;31(3):185–94.

Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Forray A, Epperson CN, Costello D, Lin H, et al. Pregnant women with posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of preterm birth. JAMA Psychiat. 2014;71(8):897–904.

Lev-Wiesel R, Chen R, Daphna-Tekoah S, Hod M. Past traumatic events: are they a risk factor for high-risk pregnancy, delivery complications, and postpartum posttraumatic symptoms? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(1):119–25.

Rosen D, Seng JS, Tolman RM, Mallinger G. Intimate partner violence, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder as additional predictors of low birth weight infants among low-income mothers. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(10):1305–14.

Screening for Perinatal Depression. Screening for perinatal depression ACOG committee opinion no. 757. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):e208-12.

Rhodes A, Segre L. Perinatal depression: A review of U.S. legislation and law. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(4):259–70.

Wenz-Gross M, Weinreb L, Upshur C. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder in prenatal care: prevalence and characteristics in a low-income population. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(10):1995–2002.

Lang AJ, Stein MB. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(5):585–94.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R, Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6.

Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska JA, Keane T. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. San Antonio; 1993.

Lydsdottir LB, Howard LM, Olafsdottir H, Thome M, Tyrfingsson P, Sigurdsson JF. The mental health characteristics of pregnant women with depressive symptoms identified by the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(4):393–8.

Thomas JL, Carter SE, DunkelSchetter C, Sumner JA. Racial and ethnic disparities in posttraumatic psychopathology among postpartum women. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;1(137):36–40.

Seng JS, Kohn-Wood LP, McPherson MD, Sperlich M. Disparity in posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis among African American pregnant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(4):295–306.

Muzik M, McGinnis EW, Bocknek E, Morelen D, Rosenblum KL, Liberzon I, et al. PTSD symptoms across pregnancy and early postpartum among women with lifetime PTSD diagnosis. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(7):584–91.

Morland L, Goebert D, Onoye J, Frattarelli L, Derauf C, Herbst M, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and pregnancy health: preliminary update and implications. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(4):304–8.

Seng JS, Li Y, Yang JJ, King AP, Low LMK, Sperlich M, et al. Gestational and postnatal cortisol profiles of women with posttraumatic stress disorder and the dissociative subtype. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2018;47(1):12–22.

Cook N, Ayers S, Horsch A. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder during the perinatal period and child outcomes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;1(225):18–31.

Hjort L, Rushiti F, Wang SJ, Fransquet P, Krasniqi S P, Çarkaxhiu S I, et al. Intergenerational effects of maternal post-traumatic stress disorder on offspring epigenetic patterns and cortisol levels. Epigenomics. 2021;13(12):967–80.

de Weerth C, Buitelaar JK. Physiological stress reactivity in human pregnancy: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(2):295–312.

Amir M, Kaplan Z, Efroni R, Kotler M. Suicide risk and coping styles in posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68(2):76–81.

Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from wave 2 of the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(3):456–65.

Trost SL, Beauregard JL, Smoots AN, Ko JY, Haight SC, Moore Simas TA, et al. Preventing pregnancy-related mental health deaths: Insights from 14 US maternal mortality review committees, 2008–17. Health Aff. 2021;40(10):1551–9.

Ferrada-Noli M, Asberg M, Ormstad K, Lundin T, Sundbom E. Suicidal behavior after severe trauma. Part 1: PTSD diagnoses, psychiatric comorbidity, and assessments of suicidal behavior. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11(1):103–12.

Enlow MB, Kitts RL, Blood E, Bizarro A, Hofmeister M, Wright RJ. Maternal posttraumatic stress symptoms and infant emotional reactivity and emotion regulation. Infant Behav Dev. 2011;34(4):487–503.

Davies J, Slade P, Wright I, Stewart P. Posttraumatic stress symptoms following childbirth and mothers’ perceptions of their infants. Infant Ment Health J. 2008;29(6):537–54.

van Ee E, Kleber RJ, Jongmans MJ. Relational patterns between caregivers with PTSD and their nonexposed children: a review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016;17(2):186–203.

Yehuda R, Engel SM, Brand SR, Seckl J, Marcus SM, Berkowitz GS. Transgenerational effects of posttraumatic stress disorder in babies of mothers exposed to the world trade center attacks during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):4115–8.

Dindo L, Elmore A, O’Hara M, Stuart S. The comorbidity of axis I disorders in depressed pregnant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(6):757–64.

Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, Kelley KE, Louik C, Hernández-Díaz S, et al. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):51.e1-8.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Post-traumatic stress disorder, NICE guideline NG116. NICE; 2018 [cited 10 May 2021]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG116

VA/DoD Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Work Group, VA/DoD. Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Reaction 2017 - VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2017 [cited 10 May 2021]. Available from: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/

Gelaye B, Zheng Y, Medina-Mora ME, Rondon MB, Sánchez SE, Williams MA. Validity of the posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD) checklist in pregnant women. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):179.

Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, Marx BP, Kimerling R, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J GEN INTERN MED. 2016;31(10):1206–11.

Alcorn KL, O’Donovan A, Patrick JC, Creedy D, Devilly GJ. A prospective longitudinal study of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from childbirth events. Psychol Med. 2010;40(11):1849–59.

LaPlante LM, Gopalan P, Glance J. Addressing intimate partner violence: Reducing barriers and improving residents’ attitudes, knowledge, and practices. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(5):825–8.

Schipani Bailey E, Byatt N, Carroll S, Brenckle L, Sankaran P, Kroll-Desrosiers A, et al. Results of a statewide survey of obstetric clinician depression practices. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;31(5):675–81.

Stevens NR, Tirone V, Lillis TA, Holmgreen L, Chen-McCracken A, Hobfoll SE. Posttraumatic stress and depression may undermine abuse survivors’ self-efficacy in the obstetric care setting. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(2):103–10.

Byatt N, Simas TAM, Lundquist RS, Johnson JV, Ziedonis DM. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;33(4):143–61.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors have no funding source information to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP, NS, MP, and MS contributed to study conception and design. NS oversaw data collection. Data management and analysis were performed by AP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AP, MC, and IE, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study included data from existing health records and was granted exemption under 45 CFR 46.104(d)(4)(iii) by the Institutional Review Board at Rush University Medical Center (project number ORA# 20111207-IRB02). Additionally, the team submitted a request to the Rush University Medical Center Research Core to work with a clinical analyst to access patient medical records. The team provided the following to the Research Core for administrative review: an initial letter from Rush IRB indicating that the study is exempt along with the study protocol describing the data and analytical needs. No further administrative permissions were required to access the data used in this study. Data were anonymized prior to analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Padin, A.C., Stevens, N.R., Che, M.L. et al. Screening for PTSD during pregnancy: a missed opportunity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 487 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04797-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04797-7