Abstract

Background

Neonatal hyperthyroidism is an extension of fetal disease. Most cases of neonatal hyperthyroidism are transient but may excessively harm multiple organ functions through the actions of maternal thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies on the neonatal thyroid gland.

Case presentation

The hyperthyroid mother underwent subtotal thyroidectomy before pregnancy and regularly took levothyroxine to avoid hypothyroidism, but still had a high-level thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb). The neonate suffered from hyperthyroidism due to the transplacental TRAb. After a regular medication schedule of an antithyroid drug, combined with a β-blocker to control the ventricular rate, the infant gradually recovered, allowing normal motor and intellectual development.

Conclusions

Maternal subtotal thyroidectomy cannot prevent the secretion of thyroid receptor antibodies, which may cause either hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. The balance between antithyroid drugs and levothyroxine is critical in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fetal hyperthyroidism usually occurs in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Neonatal hyperthyroidism tends to be an extension of disease sustained in utero; it is harmful in the fetal and neonatal periods and requires guideline-directed clinical management. Most neonatal hyperthyroidism is transient, commonly caused by stimulation by maternal thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb) crossing the placenta, resulting in a baby’s high thyroid hormone secretion. In rare situations, thyroid disease is associated with a genetic variation in the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) or G-protein alpha stimulatory subunit (GNAS) gene such as in McCune-Albright syndrome [1].

The prevalence of neonatal hyperthyroidism is 1 in 25,000 newborns to 1 in 50,000 newborns [1]. The most severe hazard in utero is prolonged tachycardia, leading to increased cardiac output, cardiac failure, and even intrauterine fetal demise. The clinical manifestations in the neonatal period are tachycardia, irritability, hyperphagia without weight gain, goiter, thyroid eye disease, small anterior fontanel, advanced bone age, hepatomegaly, and/or splenomegaly. Severely affected patients could present with cardiac failure, craniosynostosis, microcephaly, psychomotor disabilities, and even death [2]. TRAb levels should be measured in cord blood at delivery; nearly one-third of infants with increased cord blood TRAb levels develop neonatal hyperthyroidism. A newborn with such symptoms should receive timely medical intervention. If timely diagnosis and proper treatment are obtained, the prognosis of most patients is favorable. Consequently, clinicians need to monitor maternal and fetal thyroid function.

In this study, we revisit a case of a newborn child with a perinatal history of maternal thyroid disorder.

Case presentation

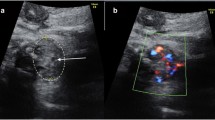

The 31-year-old mother had hyperthyroidism five years prior and took oral methimazole accordingly; however, the mother’s TRAb remained stable at over 40 IU/ml, refractory to treatment. She had undergone a spontaneous abortion three years prior and consequently underwent subtotal thyroidectomy one year prior to control the thyroid function. She regularly took levothyroxine sodium (LT4) postoperatively, and the patient was assessed to have normal thyroid function with elevating TRAb concentration from pre-gestation (T3 1.99 nmol/L, fT3 5.10 pmol/L, T4 145.5 nmol/L, fT4 17.83 pmol/L, TSH 0.58 μIU/ml, TRAb > 40 IU/ml) to the second trimesters of pregnancy (> 40 IU/ml). However, at 32 weeks of gestation, the fetal heart rate increased to 172 beats per minute, persistent for over 10 min during the electronic fetal monitoring, and thyroid ultrasound revealed fetal goiter with decreased echo. The mother The dimensions of the fetal thyroid were 75.2 mm. The obstetrician suggested withdrawing levothyroxine and introducing methimazole at a dose of 15 mg per day. In the latter part of pregnancy, we arranged pregnancy check-ups weekly. Close fetal heart rate monitoring fluctuated between 140 and 160 beats per minute. The fetal ultrasound showed neither hydrops fetalis nor cardiac hemodynamic changes. The multi-disciplinary team proposed initiating a therapeutic trial that involved concurrently administering methimazole 15 mg and levothyroxine sodium 125 μg until delivery. We monitored maternal heart rate, complete blood count, and liver function and advised adding metoprolol if necessary. The indicators above are normal, and the patient had no associated symptoms. The details of the laboratory tests of thyroid function are listed in Table 1.

A male neonate, appropriate for gestational age, was born by vaginal delivery at 37 weeks and five days with a weight of 3130 g. The newborn had no fetal distress, no maternal history of premature rupture of membranes, or neonatal asphyxia. At birth, the placenta and appendages were normal. The primary reason for hospitalization was a thyroid disorder since the gestational age of 32 weeks. Upon delivery, the child’s physical examination revealed stable vital signs, irritability, small anterior fontanel, proptosis, enlarged cardiac borders on percussion, and normal heart rate for age. The main objective of hospitalization was evaluating the primary disease and its complications.

We actively carried out relevant laboratory tests and targeted treatments for thyroid disorders. The umbilical arterial thyroid function test showed triiodothyronine (T3) 1.36 nmol/L (0.49–3.30 nmol/L), free triiodothyronine (fT3) 3.15 pmol/L (3.50–6.50 pmol/L), thyroxine (T4) 145.5 nmol/L (151.9–198.6 nmol/L), free thyroxine (fT4) 19.04 pmol/L (11.48–22.70 pmol/L), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.01 μIU/ml (1.10–19.12 μIU/ml). The serum anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (TgAb; 16.71 IU/ml) were noted, and TRAb exceeded 40 IU/ml. The thyroid ultrasound revealed an enlarged thyroid gland, and the width of the left lobe, right lobe, and isthmus of the thyroid gland was 1.1 cm, 1.2 cm, and 0.3 cm, respectively. The initial chest radiograph suggested cardiac enlargement; however, myocardial enzymes and B-type natriuretic peptide were within normal ranges. The ultrasonic cardiogram on day two showed patent ductus arteriosus (5.1 mm × 2.1 mm), and an average left ventricular ejection fraction (74%). Holter monitoring showed a heart rate of 140–200 beats per minute for 36% of the day. On the third day of life, the patient was started on a 0.4 mg of oral methimazole regimen every 12 h, at 0.25 mg/kg/day. On day seven, the patient was administered propranolol 0.5 mg every 8 h. We subsequently achieved reasonable control of the heart rate. During hospitalization, we regularly monitored thyroid function tests and TRAb levels. There was a gradual downward trend on T4, while the T3, fT3, and fT4 had no evident changes. The patient’s condition was deemed stable; meanwhile, the substantial value of TRAb was assayed for the first time before discharge. He was subsequently discharged for further outpatient follow-ups. On the 29th day of life, the TRAb level fell to 23.13 IU/ml for the first time in the patient’s clinical course. On the 51st day of life, the gradually diminishing T4, fT4, and TRAb (10.96 IU/ml) levels combined with recovering TSH levels (0.53μIU/ml) prompted us to halve the dosage of methimazole (0.125 mg/kg). On the 88th day of life, the follow-up studies showed the thyroid function test and TRAb level. Eventually, on day 98, the neonatologist discontinued all medications onboard. Meanwhile, the patient underwent a developmental assessment on routine follow-ups, appropriate for age. Details of thyroid function tests are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion and conclusion

Previous studies have shown that untreated or even partially treated overt hyperthyroidism during pregnancy could increase the risk of pregnancy loss and fetal mortality [3, 4]. Women diagnosed with hyperthyroidism should counsel the endocrinologist regarding plans for pregnancy and the adverse effects of both antithyroid drugs and LT4 during pregnancy [5]. Some studies showed that treatment with surgery before pregnancy is recommended for those who desire future pregnancy with a high TRAb level [6,7,8]. If surgery is undertaken, hypothyroidism should be treated with levothyroxine to achieve a euthyroid state before trying to conceive. Next, according to the guideline by American Thyroid Association in 2017, a maternal serum determination of TRAb is recommended at initial thyroid function testing during early pregnancy among all women with a prior history of hyperthyroidism treated with surgery [9, 10].

In this case, the mother underwent a prior miscarriage due to thyroid disorder. She underwent surgery to prevent fetal and neonatal thyroid disorder. However, the stubborn elevating TRAb level at a critical stage of pregnancy resulted in fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism and tachycardia. Considering the risk of intrauterine growth restriction, fetal bradycardia, and neonatal hypoglycemia, [11] the obstetrics and gynecology team decided against maternal administration of propranolol. It is worth noting that there is a subtle balance between maternal TRAb and thyroid hormones. The complicated regulation of maternal thyroid function is a rigorous challenge for medical intervention. Despite thyroidectomy to avoid miscarriage, the human body still secretes TRAb, which crosses transplacentally to enter the fetal circulation, resulting in hyperthyroidism during the fetal and neonatal periods. Taking ATDs could inhibit the synthesis of T3 and T4. Meanwhile, levothyroxine could protect against resultant hypothyroidism.

In this therapeutic dilemma of maternal hypothyroidism with secondary fetal hyperthyroidism, medical procedures should focus on (1) regular thyroid function screening during pregnancy. The diagnostic criteria for maternal hyperthyroidism include goiter, tachycardia (> 120 beats per minute), ophthalmopathy, and weight loss. The key laboratory finding is the thyroid function test, primarily T3, TSH, and TRAb titers [9]. (2) For women with hyperthyroidism who had previously been treated with radioactive iodine, surgery, or taking oral ATD, serum TRAb was recommended to detect in the first trimester of pregnancy. If serum TRAb is negative early in pregnancy, retesting is not required. If the result presents an elevating TRAb, retesting at 18 to 22 weeks of gestation is recommended. Serum TRAb should be tested again during the third trimester and evaluate the need for fetal and neonatal monitoring on the condition that the repeated measurement is elevated or ATD is initiated [12]. Combining the guideline in China with the clinical situations of our pregnant mother, we designed a meticulous scheme to facilitate clinical decision-making [13]. Once maternal thyroid function disorder is biochemically detected, medications are subsequently titrated to maintain a stable thyroid function for an asymptomatic status. Based on keeping normal thyroid function of the mother, clinicians should pay more attention to reasonable stability of fetal condition, including maintaining normal thyroid appearance, regional blood flow, in utero growth, and fetal heart rate. The fetus should be monitored every 4–6 weeks from mid-pregnancy until birth [14]. According to this case experience, the level of thyroid function is not parallel with the TRAb. The general treatment principle is to maintain a constant maternal thyroid function, reducing fetal complications. The goal is to prepare for the transition to neonatal treatment. (3) Hyperthyroidism patients with good antithyroid drug adherence have a lower risk of severe complications [15]. The adherence of pregnant women to therapy is of primary importance. There is no consensus on the best practice for the dosage of ATD, and the treatments are empirical. According to the condition of pregnant women and the degree of fetal goiter, the multi-disciplinary team should draw up an individual schedule. The lowest effective dose may be applied during the therapy of fetal hyperthyroidism to minimize the risk of fetal hypothyroidism. Maintaining maternal serum fT4 levels at or moderately above the upper limit of the reference range is appropriate for euthyroid fetal status.

In summary, thyroid disorders are one of the main topics in pregnancy complications. At present, more attention has been paid to the effects of hormone abnormalities on infertility, pregnancy outcomes, and long-term motor and intellectual development in offspring. Maternal and fetal diseases identification has gradually improved with the development of endocrinology, perinatology, obstetrics and gynecology, fetal medicine, pediatrics, genetics, and ultrasonic medicine. The multi-disciplinary team makes it possible to manage both maternal and fetal/neonatal thyroid disease from the prenatal period to post-delivery. For a mother with subtotal thyroidectomy, the maternal body may be in a state of hypothyroidism and high-level serum TRAb. It is challenging for clinical decisions to decrease the serum level. Identifying and managing fetal/neonatal thyroid diseases at an early stage of life and reducing long-term comorbidities are crucial issues that need to be solved. Therefore, monitoring fetal surveillance and dosage adjustment to relieve the symptomatic fetal effect without deteriorating the mom is critical.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed in the case report are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TRAb:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody

- LT4:

-

Levothyroxine sodium

- ATD:

-

Antithyroid drug

- T3 :

-

Triiodothyronine

- fT3 :

-

Free triiodothyronine

- T4 :

-

Thyroxine

- fT4 :

-

Free thyroxine

- TSH:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- TgAb:

-

Anti-thyroglobulin antibody

- TSHR:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor

- GNAS:

-

G-protein alpha stimulatory subunit

References

Samuels SL, Namoc SM, Bauer AJ. Neonatal thyrotoxicosis. Clin Perinatol. 2018;45:31–40.

Leger J. Management of Fetal and Neonatal Graves' disease. Horm Res Paediatr. 2017;87:1–6.

Turunen S, Vaarasmaki M, Lahesmaa-Korpinen AM, Leinonen MK, Gissler M, Mannisto T, et al. Maternal hyperthyroidism and pregnancy outcomes: a population-based cohort study. Clin Endocrinol. 2020;93:721–8.

Andersen SL, Olsen J, Laurberg P. Hypothyroidism and pregnancy loss: comparison with hyperthyroidism and diabetes in a Danish population-based study. Clin Endocrinol. 2016;85:962–70.

Lee SY, Pearce EN. Assessment and treatment of thyroid disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18:158–71.

Cooper DS, Rivkees SA. Putting propylthiouracil in perspective. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1881–2.

Earl R, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Interventions for hyperthyroidism pre-pregnancy and during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD008633.

Doubleday AR, Sippel RS. Hyperthyroidism Gland Surg. 2020;9:124–35.

Kobaly K, Mandel SJ. Hyperthyroidism and pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2019;48:533–45.

Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, Brown RS, Chen H, Dosiou C, et al. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease during Pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315–89.

Bateman BT, Patorno E, Desai RJ, Seely EW, Mogun H, Maeda A, et al. Late pregnancy beta blocker exposure and risks of neonatal hypoglycemia and bradycardia. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160731.

Committee C. Guideline on diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Diseases during pregnancy and postpartum (2nd edition). Chin J Perinat Med. 2019,22(8):505–39.

Seo GH, Kim TH, Chung JH. Antithyroid drugs and congenital malformations: a Nationwide Korean cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:405–13.

Korevaar TIM, Medici M, Visser TJ, Peeters RP. Thyroid disease in pregnancy: new insights in diagnosis and clinical management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:610–22.

Tsai MS, Chuang PY, Huang CH, Shih SR, Chang WT, Chen NC, et al. Better adherence to antithyroid drug is associated with decreased risk of stroke in hyperthyroidism patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:1473–85.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the patient and his family. The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

This case report was supported by Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (No. Z191100006619049) and National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFC2700700). The funder aided in the process of writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CP and XZ collected the data and wrote the manuscript; LL and XH managed the infant’s treatment and follow-ups; WS, LF and YG supervised the management and follow-ups of the mother. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the report for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Peking University First Hospital (2021–175).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of this case report was obtained from the mother for herself and the newborn child.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, C., Sun, W., Fan, L. et al. A hypothyroid mother after subtotal thyroidectomy delivered a newborn with hyperthyroidism from fetal stage: a case report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 312 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04654-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04654-7