Abstract

Background

Maternal and neonatal health outcomes remain a challenge in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) despite priority given to involving male partners in birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR). Men in LMICs often determine women’s access to and affordability of health services. This systematic review and meta-analysis determined the pooled magnitude of male partner’s participation in birth preparedness and complication readiness in LMICs.

Methods

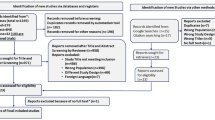

Literature published in English language from 2004 to 2019 was retrieved from Google Scholar, PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, and EMBASE databases. The Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tool for prevalence and incidence studies were used. A pooled statistical meta-analysis was conducted using STATA Version 14.0. The heterogeneity and publication bias were assessed using the I2 statistics and Egger’s test. Duval and Tweedie's nonparametric trim and fill analysis using the random-effect analysis was carried out to validate publication bias and heterogeneity. The random effect model was used to estimate the summary prevalence and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) of birth preparedness and complication readiness. The review protocol has been registered in PROSPERO number CRD42019140752. The PRISMA flow chart was used to show the number of articles identified, included, and excluded with justifications described.

Results

Thirty-seven studies with a total of 17, 148 participants were included. The pooled results showed that 42.4% of male partners participated in BPCR. Among the study participants, 54% reported having saved money for delivery, whereas 44% identified skilled birth attendants. 45.8% of male partners arranged transportation and 57.2% of study participants identified health facility as a place of birth. Only 16.1% of the male partners identified potential blood donors.

Conclusions

A low proportion of male partners were identified to have participated in BPCR in LMICs. This calls countries in low- and middle-income setting for action to review their health care policies, to remove the barriers and promote facilitators to male partner’s involvement in BPCR. Health systems in LMICs must design and innovate scalable strategies to improve male partner’s arrangements for a potential blood donor and transportation for complications that could arise during delivery or postpartum haemorrhage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) accounts for 84% of the world’s population and 93% of the global burden of disease [1, 2]. Maternal mortality continues to be disproportionately higher in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where 1 out of 39 women dies due to preventable complications of pregnancy and childbirth as compared to 1 in 3800 in Europe [3].

The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development stressed the active presence and collective responsibility of male partners in birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) [4]. Engaging men in BPCR service includes informing and encouraging them to share reproductive health burdens with their wives [5,6,7,8]. This will improve women reproductive rights and behavior as significant interventions to successful maternal and child health care [9,10,11].

Men in LMICs are the key decision-makers on matters that influence women’s access to maternal health care services [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Affordability of basic economic needs including the majority of expenses related to essential health care services, transportation to the health facility, buying clean clothes for the baby and the mother, and arrangement of skilled pre- and post-natal care is dependent on men [2, 6, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Additionally, nutritional requirements for both the mother and the fetus during pregnancy, and access to the postpartum emergency care depends on the out-of-pocket payment made by male partners [23, 30,31,32].

Studies have reported increased male partner participation in BPCR was associated with better mental health for the mother and the baby, and relief from anxiety, discomfort, and unease at the time of childbirth [20, 33,34,35]. Married couples in LMICs who properly practice BPCR show enhanced compliance with the use of skilled birth attendants, the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission program, as well as improved cognitive and socio-emotional development of children [36,37,38,39,40,41].

Furthermore, male partners involvement in BPCR is vital for improved access to prenatal and postnatal services, and discouragement of harmful maternal practices [42,43,44].

Sparse evidence from previous studies suggested that male partner participation in BPCR improves maternal and child health outcomes [45, 46]. However, the pooled magnitude of the association is not clear [47]. Previously conducted systematic reviews in both the developed and developing regions emphasized on the influence of male partners on non-maternal health areas such as child health outcomes and mother-to-child HIV/AIDS transmission in [40, 45, 46, 48, 49].

There is a gap in up-to-date evidence of the pooled magnitude of male partner involvement in BPCR to inform policy and impact practice in LMICs [43, 47, 50]. To fill the mentioned knowledge gap, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted with the aim of determining the pooled prevalence of male partner participation in BPCR in LMICs.

The review was restricted to the impact of male partners on maternal health outcomes to have a much more focused research question [51]. A preliminary search of PROSPERO [52], the Cochrane [53], and the JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports [54] were conducted and no current or underway systematic reviews on the topic were identified.

Methods

Search strategy and selection of studies

The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished literature. A preliminary search was done on Google Scholar database to identify the availability of articles on the topic. Key terms were adapted as appropriate for each database and site, with combination of MeSH terms and text words using Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” running key search topics for electronic databases such as PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Scopus (Additional file 1). The reference lists of all studies selected for critical appraisal were screened for additional studies. Both institutional and community-based cross-sectional studies published in English language from January 2004 to December 2019 were included.

Following the search, all identified citations were organized and uploaded into EndNote version 15.0 and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviews and double-checked by a third reviewer for assessment against the in- and exclusion criteria. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full including their citation details.

Literature was eligible for inclusion if they reported the involvement of male partners of pregnant women and nursing mothers in BPCR in LMICs as participants in the study. Studies which reported the magnitude of male partners' participation in BPCR as the main outcome were included. Systematic reviews, studies conducted on women participation in BPCR, studies with poor methodological quality after a quality assessment and reports of studies conducted in high-income countries were excluded.

The full text of selected citations was assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by two reviewers and double-checked by two other independent reviewers. Reasons for exclusion of studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria up on full text screening were recorded and reported. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the study selection process were resolved through discussion, or with a third reviewer. The results of the search were reported in full in the final systematic review and presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig. 1) [55].

Operational definitions

Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

Defined as planning and organizing during pregnancy in preparation for a normal delivery or in case of complications [50, 56, 57]. The BPCR practices involves saving money for delivery; identifying transport and the location of birth of the baby; knowing danger signs of pregnancy complications [58]; identifying a skilled birth attendant and a potential blood donor [50, 56, 57]. Complications were defined as: Immediate, life threatening pregnancy or labour complications [57].

Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness at a Health System Level

Is defined as a strategy of promoting the active use and retaining of well-trained human resource for maternal and neonatal health, especially during childbirth and postpartum care, based on the theory that arranging for childbirth and being prepared for complications decreases delays in receiving this care [11, 59,60,61,62].

Male partner participation in BPCR

Refers to the knowledge, attitude, and behavioral practices associated to BPCR and emergency obstetric care by male partners of pregnant women and nursing mothers within the 42 days of the delivery of the neonate [19, 56, 63,64,65,66,67,68,69].

Data extraction

The data were extracted from included studies using the data extraction tool prepared by MTB. The tool includes variables such as the name of the author, publication year, study design, data collection period, sample size, study area, and the prevalence of birth preparedness and complication readiness.

The data extraction tool contains information on the percentage of male partners who saved money for the birth of the baby, prepared a potential blood donor, identified a skilled birth attendant, and knows danger signs, arranged transportation, and identified a health facility as place of delivery of the baby. MTB extracted the data, and HT and MY cross-checked the extracted data for its validity and cleanness. Authors of papers were contacted to request missing or additional data.

Data quality and risk of bias assessment

Eligible studies were critically appraised by two independent reviewers (MTB and MY). Methodological quality was assessed using the JBI’s standardized critical appraisal instrument for incidence and prevalence studies. The results of the critical appraisal were reported in narrative form and a table. A lower risk of bias (90%) observed after assessment (Table 1).

Studies with inadequate sample size, inappropriate sampling frame and poor data analysis were excluded. Articles were reviewed using titles, abstracts, and full text screening. Full texts of included studies were examined using the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) for critical appraisal tool (Table 1).

Data analysis

Included studies were pooled in a statistical meta-analysis using STATA version 14.0. Effect sizes were expressed as a proportion with 95% confidence intervals around the summary estimate. Heterogeneity was assessed using the standard chi-square I2 test. A random-effects model using the double arcsine transformation approach was used.

Sub-group analyses were conducted to investigate the level of male partner participation in the SSA and Asian regions. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test decisions made regarding the included studies. Visual examination of funnel plot asymmetry (Fig. 2) and Egger’s regression tests were used to check for publication bias [70]. A Forest plot with 95% CI was computed to estimate the pooled magnitude of male partners’ participation in birth preparedness and complication readiness in LMICs.

Protocol registration

The review protocol has been registered in PROSPERO with protocol registration number CRD42019140752 [71].

Results

Search

After removing 108 duplicates, a total of 1751 articles were obtained from MEDLINE/PUBMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, Google Scholar, and SCOPUS databases. At the title/abstract screening phase (n=1250) and during the full-article screening (n=434) articles were excluded. Accordingly, sixty-seven studies were found eligible for quality assessment. Finally, 37 studies were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1)

Study characteristics

The total sample size of this systematic review was 17, 148, ranging from 125 in Nepal [19] to 1256 in Indonesia [72]. Seven studies were from Asia [19, 31, 72,73,74,75,76], thirty studies were from Sub-Saharan Africa [5, 22, 65, 68, 77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102]. The review was conducted on the cross-sectional study designs (Table 2).

Pooled prevalence of birth preparedness and complication readiness

The range of BPCR practice among male partners was from 6.6% to 86% (Table 2). The pooled magnitude of male partner’s participation in BPCR was 42.4% (95%CI: 33.0% - 51.8%) (Fig. 3).

Saving money for delivery was varied significantly with the lowest 15.7% and the highest 92.7% (Table 2). The pooled estimate of saving money for delivery was 45.7% (95%CI: 36.7% - 54.8%) (Fig. 4). The I2 test result showed high heterogeneity (I2 = 99.27%, p= < 0.001) and Egger’s test showed no publication bias.

Only 16.1% (95% CI: 11.5% - 20.8%) of male partners in LMICs were reported to have identified a potential blood donor for an emergency case that could occur during pregnancy or childbirth (Fig. 5). The minimum level of arrangement of potential blood donor was 0.4% and the maximum level was 47.6% (Table 1).

The proportion of male partners who identified a skilled birth attendant ranged from 0.8% to 94% (Table 1). The pooled estimate of identifying skilled birth attendant was 44.6% (95% CI: 31.3% - 57.9%) (Fig. 6).

Only 45.8% (95% CI: 33.4% - 58.2%) of male partners made transportation arrangement (Fig. 7). Arrangement of transportation by the male partners ranged from 10.2% to 88% (Table 1).

A pooled estimate of 57.2% (95% CI: 41% - 73.3%) of male partners identified health facility as a place of birth for their baby (Fig. 8). Identifying health facility ranges from 1.8% to 95.7% (Table 1).

Knowledge of the danger signs that occur during pregnancy and postpartum complications was 54% (95% CI: 40.1% - 67.8%) (Fig. 9). The study that showed the least proportion of male partners with knowledge of danger sign was 20% whereas the highest was 98.6% (Table 1).

A pooled estimate of 45.7% (95% CI: 36.7% - 54.8%) of male partners accompanied their wife/partner to antenatal care follow-up (Fig. 10). The proportion of men who had antenatal clinic follow-up together with their wife/partner was reported between 9.9% and 88.5% in the different studies (Table 1).

In the sub-group analysis, the heterogeneity test indicated the presence of heterogeneity (I2 = 94.4%, p<0.001) but no publication bias (Egger’s test p-value < 0.001). Therefore, the pooled estimate of male partner involvement in BPCR was found to be 39.8% (95% CI: 31.2% - 48.5%) in SSA and 55.7% (95% CI: 22% - 89.4%) in Asia (Fig. 3).

Discussion

In this review, we aimed to determine the pooled magnitude of male partner’s participation in birth preparedness and complication readiness in LMICs. Thirty-seven studies were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Only 44.6% of male partners in LMICs participated in BPCR.

The slow decline in maternal and neonatal mortality could be attributed to the underutilization of BPCR service among male partners in LMICs [21]. Poor financial readiness to pay for emergency cases during delivery and postpartum period significantly creates delayed access to emergency obstetrics and newborn care (EmONC) [103,104,105,106].

A wide range of male partner’s participation in identifying SBA was reported from SSA; The lowest proportion was among men in Tanzania, where <1% of men sought midwives care 0.8% [99], versus 94% of men, in Ethiopia, where the study participants had active involvement of identifying SBA [92]. The pooled estimate indicated that less than half of male partners (44.6%) in LMICs identified SBA. Failure to identify SBA by male partners of pregnant women and nursing mother, is among the main contributors to the disproportionate pregnancy-related complications in LMICs [69, 107].

Male partner’s financial readiness for costs related to delivery of the baby varied significantly in LMICs with the lowest (15.7%) reported from Ethiopia [84] and the highest (92.7%) indicated in Nigeria [5]. The pooled estimate of saving money for delivery was 45.7%. Only 16.1% of male partners in LMICs identified a potential blood donor for an emergency case that could occur during pregnancy or childbirth. Both the minimum and maximum levels of arrangement for a potential blood donor (0.4% and 47.6% respectively) were reported from Ethiopia [68, 83].

Postpartum hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal mortality and it can significantly be curbed by effective enrollment and retaining of male blood donors for readily available supply of compatible blood for women who develop complications related to pregnancy and childbirth [16, 17, 104, 105, 108,109,110]. Compared with women, male donors are less likely to be medically late or experience vasovagal responses and are typically preferred for blood donation in voluntary settings [15, 111, 112].

The distance from the male partner’s home to a health facility and shortage of transportation during postpartum emergencies are among the barriers for the delay in reaching a health facility [16, 65, 113]. Only 45.8% of male partners in LMICs arranged for transportation to take the pregnant women and nursing mothers to delivery and post-partum complications care.

The proportion of male partners who knew the danger signs that occur during pregnancy and postpartum complications in LMICs was 54%. The study populations with both the lowest and highest levels of knowledge of danger signs of pregnancy and delivery cases were registered in SSA [114, 115]. Poor knowledge of danger signs of pregnancy and childbirth was reported from Ethiopia (20%) [90] and better knowledge was reported from Nigeria (98.6%) [78]. This review has clearly indicated that there is a wide range of possible differences between contexts comparing to the scoping review done in SSA, which has reported the variation was between 42%-53% [50]. This difference might be explained in the variation in the literacy level among men in the two countries.

The pooled estimate for male partners who identified health facility as the place of delivery for the baby was 57.2%. This indicates that health systems in LMICs need to promote men’s uptake of quality antenatal care service [105, 116]. The highest and the lowest practice of identification of health facility as a place of birth for the baby were reported from SSA. Men in Tanzania showed poor involvement in identifying a health facility (1.8%) [99], while men in Ethiopia participated actively to identify health institutions for the birth of the baby 95.7% [92].

The pooled magnitude of male partners who accompanied their wife/partner to antenatal care follow up was 45.7%. Studies conducted in different parts of Ethiopia reported both the lowest (9.9%) [68] and the highest (88.5%) [94] levels of male partners who visited antenatal clinic with their wife/partner for pregnancy checkup.

Policymakers and program planners have to make targeted interventions by reviewing maternal and neonatal healthcare delivery guidelines to include context-specific evidence and develop evidence-informing interventions promoting male partner’s active involvement in birth preparedness and complication readiness.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed the magnitude of BPCR among male partners of pregnant women and nursing mothers in LMICs as updated evidence. Stringently applying the PRISMA guideline and the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistical Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) during critical appraisal was a further strength to this systematic review and meta-analysis. Restricting the search strategy to literature published in English language is the limitation of this review.

Conclusion

Previous evidence has underscored the role of the male partners in improving MNCH in low- and middle-income countries. Therefore, reviews that investigate key aspects of maternal health services such as BPCR and provide comparison across LMIC settings are critical for cross-national knowledge mobilization and learning. This study has included representative quality studies from across LMIC’s. In this study, a low proportion of male partners participated in BPCR in LMICs. However, the proportion ranged from 6 to 86%. This variation across LMIC regions requires a closer examination of the reasons for the high achieving settings, which have the potential to illuminate a new insight for policymakers.

The low proportion of male partners involvement in BPCR in this study calls for action for countries in low- and middle-income setting to review their health care policies, remove the barriers and promote facilitators to male partner’s involvement in BPCR. These could be achieved through behavioural interventions targeting male partner’s awareness, positive role-modelling, male community health workers and other tested interventions which improve male engagement. Health systems in LMICs must design and innovate scalable strategies suitable to their context to improve male partner’s practice of arrangements for a potential blood donor and transportation for complications that could arise during pregnancy or postpartum haemorrhage. Further, large scale systematic reviews and meta-analysis that addresses the various factors of hierarchical societal arrangements at the individual, filial, social, political, and economic levels are needed to facilitate understanding of the gendered aspects of maternal health care services.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available up on request of the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- BPCR:

-

Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

- EmONC:

-

Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care

- JBI:

-

The Joanna Briggs Institute

- JBI – MAStARI:

-

The Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistical Assessment and Review Instrument

- LMICs:

-

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Registry of Systematic Reviews

- SBA:

-

Skilled Birth Attendant

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

References

Schieber G, Maeda A. Health care financing and delivery in developing countries. Health Aff. 1999;18:193–205.

WHO. Global Spending on Health: A World in Transition 2019. Glob Rep 2019;49.

WHO. Maternal Mortality Fact sheet. Matern Heal 2015;2015:1–5.

Tobergte DR, Curtis S. Program of Action_Adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo 1994. 2013. Epub ahead of print 2013. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Erhabor JO, Okpere E, Lawani LO, Omozuwa ES, Eze P. A community-based assessment of the perception and involvement of male partners in maternity care in Benin-City, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore) 2020;0:1–7.

Gharoro EP, Igbafe AA. Antenatal care: Some characteristics of the booking visit in a major teaching hospital in the developing world. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:519–22.

Adamu H, Oche OM, Kaoje AU. Effect of health education on the knowledge, attitude and involvement by male partners in birth preparedness and complication readiness in rural communities of sokoto state, nigeria. Am J Public Health. 2020;8(5):163–75.

Thapa DK, Niehof A. Women’s autonomy and husbands’ involvement in maternal health care in Nepal. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:1–10.

Shand T, Marcell AV. Engaging men in sexual and reproductive health. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health 2021.

Çelik A, Yaman H, Turan S, Kara A, Kara F, et al. Assessing Men‟S Knowledge and Perceptions of Male Involvement in Maternal and Child Health Services and their Influence on Clinic Attendance in Suba Sub County Kenya. J Mater Process Technol. 2018;1:1–8.

Justyna W. Male Involvement and Accommodation During Obstetric Emergencies in Rural Ghana: A Qualitative Analysis. Physiol Behav. 2017;176:139–48.

Nesane K, Maputle SM, Shilubane H. Male partners’ views of involvement in maternal healthcare services at Makhado Municipality clinics, Limpopo Province, South Africa. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2016;8:1–5.

Kassa MC, Abate HK, Demessie NG. Male involvement in birth preparedness and complication readiness in Ethiopia: A Systematic review and Meta-analysis. 2020. p. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-55935/v2.

Hernandez DC, Coley RL. Measuring Father Involvement Within Low-Income Families: Who is a Reliable and Valid Reporter? 2007. Epub ahead of print 2007. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295190709336777.

Rahman AE, Perkins J, Salam SS, Mhajabin S, Hossain AT, et al. What do women want? An analysis of preferences of women, involvement of men, and decision-making in maternal and newborn health care in rural Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–12.

Sumankuuro J, Crockett J, Wang S. Factors influencing knowledge and practice of birth preparedness and complication readiness in sub-saharan Africa: a narrative review of cross-sectional studies. Int J Community Med Public Heal. 2016;3:3297–307.

Awareness of husbands regarding birth preparedness and complication readiness in district Rawalpindi. 2019;69:259–66.

Sharma S, Aryal UR, Shrestha A. Factors influencing male participation in maternal health care among married couples in Nepal: a population-based cross-sectional study. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2020;71(3):228–34.

Bhusal CK, Bhattarai S. Social Factors Associated with Involvement of Husband in Birth Preparedness Plan and Complication Readiness in Dang District, Nepal. J Community Med Health Educ;08. Epub ahead of print 2018. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.1000636.

Bielinski-Blattmann D, Lemola S, Jaussi C, Stadlmayr W, Grob A. Postpartum depressive symptoms in the first 17 months after childbirth: The impact of an emotionally supportive partnership. Int J Public Health. 2009;54:333–9.

Adgoy ET. Key social determinants of maternal health among African countries: a documentary review. MOJ Public Heal. 2018;7:140–4.

Ibrahim SM, Aminu BM, Usman HA, Umaru UD, Kullima AA, et al. Factors Influencing Husbands’ Involvement in Ante Natal Care Services in a Nigerian Urban Region. J Biomed Res Clin Pract. 2019;2:32–9.

Inhon M, Dudgeon M. Men’s influences on women’s reproductive health. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1379–95.

Maluka SO, Peneza AK. Perceptions on male involvement in pregnancy and childbirth in Masasi District, Tanzania: A qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2018;15:1–7.

Banos JP, Banos C, Moumouni Z. Constraints faced by hospitalized maternity patients in Niamey (Niger). Sante (Montrouge, France). 1996;6(6):345–51.

UHAWENIMANA T. Factors influencing whether or not male partners from low and middle income countries attend childbirth: a mixed methods systematic review. 2019;1–35.

Muula AS. What can Mchinji and Ntcheu districts in Malawi tell maternal health pundits globally? Croat Med J. 2010;51:89–90.

Hytti L. Fluid cash and discordant households: exploring perceptions of and attitudes towards saving for childbirth: a qualitative study in Pallisa district, Uganda. 2015;4:1–45.

Singh D, Lample M, Earnest J. The involvement of men in maternal health care: Cross-sectional, pilot case studies from Maligita and Kibibi Uganda. Reprod Health. 2014;11:1–8.

Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Galadanci HS, Aliyu MH. Birth preparedness, complication readiness and fathers’ participation in maternity care in a northern Nigerian community. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14:21–32.

Ampt F, Mon MM, Than KK, Khin MM, Agius PA, et al. Correlates of male involvement in maternal and newborn health: A cross-sectional study of men in a peri-urban region of Myanmar. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:1–11.

Comrie-Thomson L, Tokhi M, Ampt F, Portela A, Chersich M, et al. Challenging gender inequity through male involvement in maternal and newborn health: critical assessment of an emerging evidence base. Cult Heal Sex. 2015;17:177–89.

D’Aliesio L, Vellone E, Amato E, Alvaro R. The positive effects of father’s attendance to labour and delivery: a quasi experimental study. Int Nurs Perspect. 2009;9(1):5–10.

Gremigni P, Mariani L, Marracino V, Tranquilli AL, Turi A. Partner support and postpartum depressive symptoms. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2011;32:135–40.

Grube M. Inpatient treatment of women with postpartum psychiatric disorders - The role of the male partners. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:163–70.

Guthrie K, Taylor DJ, Defriend D. Maternal hypnosis induced by husbands during childbirth. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). Epub ahead of print 1984. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443618409109124.

Henneborn WJ, Cogan R. The effect of husband participation on reported pain and probability of medication during labor and birth. J Psychosom Res. 1975;19:215–22.

O’hara MW. Social Support, Life Events, and Depression During Pregnancy and the Puerperium. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986;43:569–573.

Yue K, O’Donnell C, Sparks PL. The effect of spousal communication on contraceptive use in Central Terai Nepal. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:402–8.

Morfaw F, Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Rodrigues C, Wunderlich AP, et al. Male involvement in prevention programs of mother to child transmission of HIV: a systematic review to identify barriers and facilitators. Syst Rev. 2013;2:5.

Moshi FV, Ernest A, Fabian F, Kibusi SM. Knowledge on birth preparedness and complication readiness among expecting couples in rural Tanzania: Differences by sex cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:1–15.

Martin LT, McNamara MJ, Milot AS, Halle T, Hair EC. The effects of father involvement during pregnancy on receipt of prenatal care and maternal smoking. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:595–602.

Plantin L, Olukoya AA, Ny P. Positive Health Outcomes of Fathers’ Involvment in Pregnancy and Childbirth Paternal Support: A Scope Study Literature Review. Father A J Theory, Res Pract about Men as Father. 2011;9:87–102.

Schaffer M a, Lia-hoagberg B. and Health Behaviors of Low-Income Women. 1991;433–440.

Alio AP, Salihu HM, Kornosky JL, Richman AM, Marty PJ. Feto-infant health and survival: Does paternal involvement matter? Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:931–7.

Sarkadi A, Kristiansson R, Oberklaid F, Bremberg S. Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. 2008;97:153–8.

Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:604–12.

Brusamento S, Ghanotakis E, Tudor Car L, van-Velthoven MH, Majeed A, et al. Male involvement for increasing the effectiveness of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) programmes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Epub ahead of print 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd009468.pub2.

Ditekemena J, Koole O, Colebunders R. Determinants of male involvement in maternal and child health services in sub-Saharan Africa : a review Introduction Methods Participants, interventions and outcome. Reprod Health. 2012;9:1–8.

Forbes F, Wynter K, Zeleke BM, Fisher J. Male partner involvement in birth preparedness , complication readiness and obstetric emergencies in Sub-Saharan Africa : a scoping review. 2021;1–20.

Kamal IT. Field experiences in involving men in safe motherhood. Program Male Involv Reprod Heal Rep Meet WHO Reg Advis Reprod Heal WHO/PAHO. 2001;2002:63–84.

NIHR. International prospective register of systematic reviews Registering a Systematic review on PROSPERO What does registration on PROSPERO involve ? Inclusion criteria When to register your review PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic rev. 2019;1–12.

Palaskar J. Cochrane systematic review protocols. J Dent Allied Sci. 2015;4:63.

Peters Micah DJ, BHSc MA(Q) PhD Not just a phase: JBI systematic review protocols, JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports: 2015;13(2):1–2. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2217.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med;6. Epub ahead of print 2009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Soubeiga D, Gauvin L, Hatem MA, Johri M. Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) interventions to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality in developing countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth;14. Epub ahead of print 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-129.

Miltenburg AS, Roggeveen Y, Shields L, Van Elteren M, Van RJ, et al. Impact of birth preparedness and complication readiness interventions on birth with a skilled attendant: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:1–21.

Dunn A, Haque S, Innes M. Rural Kenyan Men’s awareness of danger signs of obstetric complications. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;10:1–9.

JHPIEGO. Monitoring Tools Birth Preparedness & Complication Readiness (BPCR). 2004;338.

Punam D, Bhawana B. Male participation in safe motherhood in selected village development committee of Morang, Nepal, 2016. Diabetes Manag. 2017;7:210–7.

Asefa F. Male Partners Involvement in Maternal ANC Care: The View of Women Attending ANC in Hararipublic Health Institutions Eastern Ethiopia. Sci J Public Heal. 2014;2:182.

Ntoimo L favour, Okonofua FE, Adejumo O, Imongan W, Ogu R, et al. Assessment of interventions in Primary Health Care for improved maternal, new-born and child health in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. 2019;1–34.

Onchong JM. Male Partner Involvement in Choice of Delivery Site among Women Delivering at Coast Level Five Hospital Mombasa County , Kenya James Maina Onchong ’ A , ( BScN ). 2015;1–71.

Wiafe E. Male Involvement In Family Planning In The Sunyani Municipality. 2015;1–102.

Gibore NS, Ezekiel MJ, Meremo A, Munyogwa MJ, Kibusi SM. Determinants of men’s involvement in maternity care in dodoma region, central Tanzania. J Pregnancy;2019. Epub ahead of print 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7637124.

Aborigo RA, Reidpath DD, Oduro AR, Allotey P. Male involvement in maternal health: Perspectives of opinion leaders. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:1–10.

Berhe AK, Muche AA, Fekadu GA, Kassa GM. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Ethiopia: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2018;15:1–10.

Mersha AG. Male involvement in the maternal health care system: Implication towards decreasing the high burden of maternal mortality. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:1–8.

Aguiar C, Jennings L. Impact of Male Partner Antenatal Accompaniment on Perinatal Health Outcomes in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:2012–9.

Copas JB, Shi JQ. A sensitivity analysis for publication bias in systematic reviews. Stat Methods Med Res. 2001;10:251–65.

International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). Systematic review registration protocol; CRD42019140752. 2020;6:1–12.

Kurniati A, Chen CM, Efendi F, Elizabeth Ku LJ, Berliana SM. Suami SIAGA: Male engagement in maternal health in Indonesia. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:1203–11.

Oktaviana B, Helda. Husband participation in birth prepareness and complication readiness and utilization of delivery services in Indonesia. Indian J Public Heal Res Dev 2019;10:406–412.

May Chan OO, San San Myint Aung, Alessio Panza. Are Husbands Involving in Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness for their Wives’ Pregnancies?: A Cross-Sectional Study in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar. Int Healthc Res J 2019;3:23–31.

Rahman AE, Perkins J, Islam S, Siddique AB, Moinuddin M, et al. Knowledge and involvement of husbands in maternal and newborn health in rural Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:1–12.

Zaman S Bin, Gupta R Das, Al Kibria GM, Hossain N, Bulbul MMI, et al. Husband’s involvement with mother’s awareness and knowledge of newborn danger signs in facility-based childbirth settings: A cross-sectional study from rural Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes 2018;11:4–9.

Nwakwuo GC, Oshonwoh FE. Assessment of the level of male involvement in safe motherhood in Southern Nigeria. J Community Health. 2013;38:349–56.

Falade-Fatila O, Adebayo AM. Male partners’ involvement in pregnancy related care among married men in Ibadan Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2020;17:1–12.

Sa A. Predictors of Male Involvement in Post-Natal Care Services of their Partners in a Metropolitan City in North-Central Nigeria. Texila Int J Public Heal. 2020;8:27–34.

Shine S, Derseh B, Alemayehu B, Hailu G, Endris H, et al. Magnitude and associated factors of husband involvement on antenatal care follow up in Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia 2016: A cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–7.

Demissie DB, Bulto GA, Terfassa TG. Involvement of male in antenatal care, birth preparedness and complication readinessand associated factors in Ambo town, Ethiopia. J Health Med Nurs. 2016;27(5):14–23.

Sodo W. Husbands ’ participation in birth preparedness and complication readiness and associated factors in. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med 2018;1–8.

Baraki Z, Wendem F, Gerensea H, Teklay H. Husbands involvement in birth preparedness and complication readiness in Axum town, Tigray region, Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–8.

Gidey G. Assessment of Husbands’ Participation on Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness in Enderta Woreda, Tigray Region, Ethiopia, 2012. J Women’s Heal Care. 2014;03:1–7.

Gebrehiwot Weldearegay H. Determinant Factors of Male Involvement in Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness at Mekelle Town; a community Based Study. Sci J Public Heal. 2015;3:175.

Gemechu BL, Ketema K, Beresa G, Ami B, Urgessa A. Association between Male Involvement in Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness and women’s use of institutional delivery in West Arsi Zone South Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study. 2020;1–21.

Gize A, Eyassu A, Nigatu B, Eshete M, Wendwessen N. Men’s knowledge and involvement on obstetric danger signs, birth preparedness and complication readiness in Burayu town, Oromia region. Ethiopia BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–9.

Mohammed BH, Johnston JM, Vackova D, Hassen SM, Yi H. The role of male partner in utilization of maternal health care services in Ethiopia: a community-based couple study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–9.

Pambour E. Birthing in Girar Jarso woreda of Ethiopia (Doctoral dissertation, University of Saskatchewan). 2015;19:100–11.

In I, Health M, Service C, Factors A, Shashemene IN. By: lelise melkamu.

Worku M, Boru B, Amano A, Musa A. Male involvement and associated factors in birth preparedness and complication readiness in Debre Berhan town, north east Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35:1–9.

Paulos K, Awoke N, Mekonnen B, Arba A. Male involvement in birth preparedness and complication readiness for emergency referral at Sodo town of Wolaita zone, South Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–7.

Mohammed A. Husband ’ s Knowledge and Involvement in the Reproductive Rights of Women in Harar , Eastern Ethiopia. 1–16.

Getachew F, Abate S, Solomon D, Fekade E, Molla G. Men ` s knowledge towards obstetric danger signs and their involvement on birth preparedness in Aneded woreda. Amhara Regional State, Northwest. 2013;3:39–45.

Debiso AT, Gello BM, Malaju MT. Factors Associated with Men’s Awareness of Danger Signs of Obstetric Complications and Its Effect on Men’s Involvement in Birth Preparedness Practice in Southern Ethiopia, 2014. Adv Public Heal. 2015;2015:1–9.

Tadesse M, Boltena AT, Asamoah BO. Husbands’ participation in birth preparedness and complication readiness and associated factors in Wolaita Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2018;10:1–8.

Annoon Y, Hormenu T, Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Ameyaw EK, et al. Perception of pregnant women on barriers to male involvement in antenatal care in Sekondi Ghana. . Heliyon. 2020;6:e04434.

Matiang’i M, Mojola A, Githae M. Male involvement in antenatal care redefined: A cross-sectional survey of married men in Lang’ata district, Kenya. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health 2013;7:117–122.

August F, Pembe AB, Mpembeni R, Axemo P, Darj E. Men’s knowledge of obstetric danger signs, birth preparedness and complication readiness in Rural Tanzania. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–12.

Kalisa R, Malande OO. Birth preparedness, complication readiness and male partner involvement for obstetric emergencies in rural Rwanda. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:91.

Sodeinde KJ, Amoran OE, Abiodun OA. Male involvement in birth preparedness in Ogun State, Nigeria: A rural/urban comparative cross-sectional study. Afr J Reprod Health. 2020;24:70–84.

Mbadugha C, Anetekhai C, Obiekwu A, Okonkwo I, Ingwu J. Adult male involvement in maternity care in Enugu State, Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Midwifery. 2019;3:1–7.

104.Målqvist M, Yuan B, Trygg N, Selling K, Thomsen S. Targeted Interventions for Improved Equity in Maternal and Child Health in Low- and Middle-Income Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One;8. Epub ahead of print 2013. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066453.

Solnes Miltenburg A, Roggeveen Y, Roosmalen J, Smith H. Factors influencing implementation of interventions to promote birth preparedness and complication readiness. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:1–17.

Geleto A, Chojenta C, Musa A, Loxton D. Barriers to access and utilization of emergency obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of literature 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. Syst Rev. 2018;7:1–14.

Assefa EM, Berhane Y. Delays in emergency obstetric referrals in Addis Ababa hospitals in Ethiopia: a facility-based, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e033771.

108.Suandi D, Williams P, Bhattacharya S. Does involving male partners in antenatal care improve healthcare utilisation? Systematic review and meta-analysis of the published literature from low- and middle-income countries. Int Health 2019;1–15.

Snelgrove JW. Postpartum haemorrhage in the developing world a review of clinical management strategies. Mcgill J Med. 2009;12:61.

Mohammed S, Yakubu I, Awal I. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Women’s Perspectives on Male Involvement in Antenatal Care, Labour, and Childbirth. J Pregnancy;2020. Epub ahead of print 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6421617.

Ghani U, Crowther S, Kamal Y, Wahab M. The significance of interfamilial relationships on birth preparedness and complication readiness in Pakistan. Women and Birth. 2019;32:e49–56.

Carver A, Chell K, Davison TE, Masser BM. What motivates men to donate blood? A systematic review of the evidence. Vox Sang. 2018;113:205–19.

Redshaw M, Henderson J. Fathers’ engagement in pregnancy and childbirth: Evidence from a national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:1.

Shahjahan M, Mumu SJ, Afroz A, Chowdhury HA, Kabir R, et al. Determinants of male participation in reproductive healthcare services: A cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2013;10:2–7.

Sekoni OO, Owoaje ET. Male knowledge of danger signs of obstetric complications in an urban city in South west Nigeria. Ann Ibadan Postgrad Med. 2014;12:89–95.

Galle A, De Melo M, Griffin S, Osman N, Roelens K, et al. A cross-sectional study of the role of men and the knowledge of danger signs during pregnancy in southern Mozambique. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–14.

Say L, Donner A, Gülmezoglu AM, Taljaard M, Piaggio G. The prevalence of stillbirths: A systematic review. Reprod Health. 2006;3:1–11.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Joanna Briggs Institute and Armauer Hansen Research Institute, for providing the opportunity to attend the comprehensive systematic review training, enabling and creating access to the databases.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MTB, MBS and ASK; was involved in a principal role in the conception of ideas, developing methodologies, and writing the article. HT and MY, were involved in the analysis while ATB, BOA, and ZEK participated in the analysis, interpretation and writing. ATB and ZEK involved in proofreading, and writing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Boltena, M.T., Kebede, A.S., El-Khatib, Z. et al. Male partners’ participation in birth preparedness and complication readiness in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 556 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03994-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03994-0