Abstract

Background

Despite many guidelines for the management of gestational diabetes available internationally, little work has been done to summarize and assess the content of existing guidelines. A paucity of analysis guidelines within in a unified system may be one explanatory factor. So this study aims to analyze and evaluate the contents of all available guidelines for the management of gestational diabetes.

Method

Relevant clinical guidelines were collected through a search of relevant guideline websites and databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, etc.). Fourteen guidelines were identified, and each guideline was assessed for quality using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument. Two independent reviewers extracted guideline recommendations using a “recommendation matrix” through which basic guideline information and consistency between search strategy and selection of evidence, between selected evidence and interpretation, and between interpretation and resulting recommendations were analyzed.

Results

Fourteen documents were analyzed, and a total of 361 original recommendations for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) management were assessed. In all guidelines included, the recommendations were developed in five domains, namely, diagnosis of GDM, prenatal care, intrapartum care, neonatal care and postpartum care. Different guidelines appeared to have significant discrepancy in consistency of guideline content, but overall, there was consistency between search strategy and selection of evidence, between selected evidence and interpretation, and between interpretation and resulting recommendations (scilicet 49.31, 57.20 and 58.17%, respectively).

Conclusion

Although commonality in most recommendations existed, there were still some discrepancies between guidelines. Consistency of guidelines on the management of GDM in pregnancy is highly variable and needs to be improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a special form of diabetes in women of child-bearing age and is a common gestational endocrine disease [1]. Due to its increasing prevalence, GDM results in significant short- and long-term impairments in the individual’s health and their offspring’s health [2,3,4,5,6]. Consistent evidence from high-quality randomized controlled trials over the last few decades has determined that proper management is effective in ensuring pregnancy outcomes and long-term outcomes in GDM women [7, 8]. However, management of GDM in the real world of clinical practice seems to be unsatisfactory [9], so it is necessary to standardize the management of GDM.

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are statements that include recommendations intended to assist providers and recipients of healthcare and other stakeholders to make informed decisions, and they are effective tools for disseminating medical knowledge [10]. With regard to the management of GDM, there are an abundance of available guidelines [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Health professional organizations like the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) update their management guidelines regularly [20, 21]. In mainland China and Hong Kong, based on international guidelines on pregnancy and diabetes mellitus, contextual guidelines for GDM management have been established through expert consensus [22, 23]. As the most authoritative form, CPGs have the potential to influence the care delivered by a large number of healthcare providers and consequently the outcomes for patients, so it is universally acknowledged that the methodological quality of guidelines is very important and should be appraised [24, 25]. Our previous research found that, in general, the quality of GDM guidelines was relatively higher than that in the previous year [26], while the domains of Rigor of Development, Stakeholder Involvement and Editorial Independence of guidelines still needed to be improved.

However, methodological quality of guideline is not the only way to evaluate a guideline. Whether guidelines provide valid recommendations is an aspect of particular importance to practitioners. It is noted that there may be conflict between methodological quality and the validity of recommendations, and current guidelines differ substantially in their management recommendations [27]. Whether the recommendations are in accordance with evidence and whether the recommendations suit the local context are unknown. This makes it hard for the busy practitioners, confronted with conflicting guideline recommendations, to determine which guideline to follow [27]. Many researchers are aware of the fact that it is imperative to find a unified system for evaluating the validity of recommendations. However, little work has been done in this area. In order to better ascertain the best treatment for GDM women and whether recommendations in current guidelines are valid or not, extracting and appraising the content of current guidelines are crucial. Therefore, the aim of this study was to extract and evaluate the recommendations included in guidelines for GDM management using a recommendation matrix (details in another article under review).

Methods

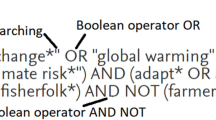

A search was conducted in CPGs for GDM management. The search strategy used the keywords “pregnancy”, “gravida*”, “conception”, “maternity”, “diabetes”, “hyperglycemia”, “insulin resistance”, “glucose intolerance”, “guideline”, “criteria”, “recommendation” and “standard”. Information sources were identified from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), China Medlive, American Diabetes Association (ADA), Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA), International Diabetes Federation (IDF), PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Chinese Periodical Database and VIP Chinese Periodical Database. The eligibility criteria included: ①full guideline that were available in English or Chinese; ②guidelines which contained recommendations regarding GDM interventions; ③guidelines that were issued between 2009 and 2018. Two independent reviewers selected documents for inclusion and appraised the methodological quality with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument.

Based on the quality evaluations, the reviewers summarized recommendations in guidelines and assessed the content of guidelines by establishing a “recommendation matrix” (Table 1 as an example). For each included document, we extracted the following information: title of guideline, author, development institute (e.g. government, special organization, etc.), year of publication, guideline type, methodological quality (appraised with AGREE II) and relevant recommendations. For all recommendations extracted, we assessed whether or not they explicitly recommended with the consistency across search strategies, selection of evidence, evidence interpretation and resulting recommendations. Each of the recommendations was rated on a seven-point scale (1-strongly inconsistent to 7-strongly consistent). A quality score was calculated in the same way used in AGREE II [28], that is, for each recommendation, the score was calculated by summing up all the scores of the individual items and by scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score [28]. If the guideline provided more complete information, we also extracted supporting evidence and the evidence level if the evidence has been cited, and the likelihood of applying the recommendation in China. For all guidelines, the recommendations were divided into five domains, namely, diagnosis of GDM, prenatal care, intrapartum care, neonatal care and postpartum care.

Initially, two researchers (Yingfeng Zhou and Mengxing Zhang) independently analyzed one guideline with the recommendation matrix in order to identify the validation and feasibility of the tool before determine the final result. Then the final form was used to extract recommendations content from the other guidelines. Frequent communication occurred between two researchers throughout the process so as to maximize inter-rater reliability. Any disagreements were settled through consultation with the study groups.

Descriptive statistics were conducted in order to characterize the recommendation content. For quantitative data, the statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Office 2013 and SPSS Version 25.0. The total number, percentages, and mean, and standard deviation were calculated to describe the consistency of recommendations. In addition, a radar chart was also used to identify features of recommendation consistency in different aspects.

This article is part of a guideline adaptation project. The Guideline Adaptation Project has been registered in the International Guideline Register Center (http://www.guidelines-registry.cn), Registration number: IPGRP-2016CN015.

Results

Characteristics of included guidelines

Combining all searches yielded 108 relevant documents, of which 14 guidelines from international organizations were included: ADA (American Diabetes Association), NCC-WCH (National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health), IDF (International Diabetes Federation), FIGO (The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics), CMA (Chinese Medical Association), DDG (German Diabetes Association), A.N.D. (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics), API (The Association of Physicians of India), CDA (Canadian Diabetes Association), HKCOG (The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists), American Endocrine Society, NZGG (New Zealand Guidelines Group), SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network), and Queensland Department of Health. See Fig. 1 for the flow diagram of the document selection process. Characteristics of the final included items are shown in Table 2.

According to systematically evaluation with AGREE II instrument, the methodological quality of guidelines included varied. But generally, they scored well. Scores for six AGREE II domains (Mean ± SD) were:88% ± 0.15 (Scope and Purpose), 73% ± 0.30 (Stakeholder Involvement), 60% ± 0.29 (Rigor of Development), 89% ± 0.19 (Clarity of Presentation), 70% ± 0.34 (Applicability), 70% ± 0.41 (Editorial Independence).

Comparison and summary of recommendations

Using the recommendation matrix, all relevant guideline information and recommendations included were extracted, and all health questions of each guideline were placed in the recommendation matrixes (Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14). For example, we extracted the NICE guideline, which is displayed in Table 1. The NICE guideline was developed based on evidence, and the development process was distinctly clarified. The guideline group graded evidence and recommendations by Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system. With regard to health question “target blood glucose values”, the results of recommendation appraisal revealed high consistency in search strategy and selection of evidence, evidence and interpretation, as well as interpretation and resulting recommendations.

The effectiveness categorization of each domain based ons the recommendations was presented in Table 3. The similarities and differences between the different guidelines on each domain were discussed below.

Diagnosis of GDM

The first domain was diagnosis of GDM, which covered three health questions: risk factors of GDM, GDM screening and diagnostic criteria. Risk factors for GDM were identified in five guidelines [12, 21,22,23, 29], mainly including personal and family history, relevant medical history, past pregnancy and current history. It was noted that threshold of some risk factors were discrepant in different guidelines. As an example, advanced maternal age, obesity BMI and macrosomia weighing in Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (HKCOG) guideline [22] had a much smaller value then in western countries. NICE guideline recommended that pregnant women with risk factors should be screened, while other guidelines recommended that universal screening was preferred. As to diagnostic criteria, the International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) (2010) criteria was adopted by most guidelines. In this study, eight guidelines [11, 13, 16,17,18, 22, 23, 29] included used IADPSG (2010) criteria, recommending that GDM should be diagnosed at any time in pregnancy if one or more of the following criteria were met following a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT): 1) fasting PG 5.1–6.9 mmol/L; 2) 1-h PG ≥ 10.0 mmol/L; 3) 2-h PG 8.5–11.0 mmol/L, while six other guidelines recommended alternatives.

Prenatal care

Prenatal care was a very crucial domain of GDM management. All guidelines agreed that it was necessary to encourage GDM women to take prenatal care. All guidelines, excepting the A.N.D. guideline [11] that only mentioned nutrition therapy, made recommendations in similar aspects of prenatal interventions more or less, which might refer to health education, medical nutrition therapy, physical activity, pharmacological therapy, blood glucose monitoring, target blood glucose values, ketone monitoring, HbA1c monitoring, continuous glucose monitoring and fetal assessment. The main principles included: ①offer all women ongoing treatment by multidisciplinary health professionals once they were diagnosed; ②lifestyle intervention was a primary and essential component of management, especially nutrition therapy; ③medical therapy should be started if needed to achieve glycemic targets; and ④ self-monitoring of blood glucose regularly should be emphasized. However, recommendations of a similar theme were not always unanimous in different guidelines. For example, six guidelines [12, 14, 19, 20, 23, 29] recommended that insulin was the preferred medication for treating hyperglycemia in GDM. On the contrary, other six guidelines [13, 16,17,18, 21, 22] did not regard insulin as the first option when drug treatment was required, since it was proved that oral antidiabetic agents was safe and might even significantly reduce several adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes (Table 4). In addition, women’s preferences and the ability to adhere to medication and self-monitoring were also considered in different guidelines.

Intrapartum care

The intrapartum care domain contained timing and mode of birth and glycemic control. Each guideline differed slightly on recommendations for timing and mode of birth, however, commonality in the way in which timing and mode of birth was decided was described, in other words, depending on whether there were maternal or fetal complications. Recommendations for glycemic control during labor and birth were similar for most guidelines, namely, monitoring capillary plasma glucose during labor and birth, and ensuring that it was maintained in normal glucose values (five guidelines [12, 13, 17, 18, 21] recommended to maintain blood glucose levels between 4 and 7 mmol/L).

Neonatal care

The fourth domain was neonatal care, that is, neonatal hypoglycemia and neonatal initial assessment. Only five guidelines [12, 15, 17, 21, 23] mentioned recommendations for neonatal hypoglycemia, advising to avoid neonatal hypoglycemia through measuring the infant’s plasma glucose frequently and early feeding. In addition, for newborns who had clinical signs associated with neonatal complications, NICE guidelines also made additional recommendations for neonatal initial assessment and criteria for admission to intensive or special care.

Postpartum care

Postpartum care was a domain involving medicines and breastfeeding after delivery, information and follow-up after birth and postnatal testing. Most guidelines recommended that GDM women should discontinue blood glucose-lowering therapy immediately after birth, but HKCOG guidelines [22] emphasized that those women could also resume or continue to take metformin and glibenclamide after birth as required. Early and exclusively breastfeeding was highly encouraged, for its benefits for both mother and infant. Regarding postnatal education, it was unanimously agreed in all guidelines that women diagnosed with GDM should be informed of the increased risk of GDM in a subsequent pregnancy and the increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes. Hence, it was important to provide them with advice on how to maintain a healthy lifestyle and information on postnatal testing. Recommendations for postnatal testing were slightly different. The method of postnatal testing can be OGTT or HbA1c (with or without fasting glucose). And testing time ranged from the initial month to 6 months, mainly between six to 12 weeks after birth. Then assessment of glycemia using fasting glucose or HbA1c should be carried out at regular intervals thereafter.

Assessment of consistency

A total of 361 original recommendations for GDM management which were from 14 guidelines were included. Although some recommendations did not fall into any of the identified themes, we undertook consistency appraisal of these as well. As presented in Table 5, different guidelines appeared to have significant discrepancies in consistency of guideline content. Even in the same guideline, consistency differed in three aspects: ①consistency between search strategy and selection of evidence, ②consistency between selected evidence and interpretation, and ③consistency between interpretations and resulting recommendations. Among all guidelines included, NICE guidelines showed the best average score of consistency in each aspect. However, HKCOG guidelines and CMA guidelines received extremely low scores in each aspect. Apparently, in this study, evidence-based guidelines rated relatively higher in content consistency than expert consensus-based guidelines. Consistency appraisal of each guideline is presented in Fig. 2. For consistency in each aspect, most guidelines showed the same tendency, that is, a guideline which received high average scores could also receive high scores in the other two aspects, and, conversely, low average scores in all aspects. When it came to all recommendations, search strategy and selection of evidence were slightly inconsistent. The radar chart showing comparable consistency between search strategy and selection of evidence, between selected evidence and interpretation, and between interpretation and resulting recommendations (scilicet 49.31, 57.20 and 58.17%, respectively) is presented in Fig. 3.

Discussion

Gestational diabetes mellitus is a challenging complication of pregnancy that many women and doctors struggle with. In this review, we examined the existing guidelines on the management for GDM in 11 countries or regions. Given that appropriate methodologies and rigorous strategies in the guideline development process are crucial for guideline implementation [25], the development methods of the guidelines were measured using the AGREE II instrument. In general, the quality of GDM guidelines, especially evidence-based guidelines, was high. This could be explained by the fact that much progress has been made in the development of methodological and reporting criteria of evidence-based guidelines within the past decade [30]. Nonetheless, as the results in previous study revealed, the domains of Rigor of Development, Stakeholder Involvement and, Editorial Independence still need to be improved [26].

It is noted that practice guidelines with the best methodological quality were not necessarily the most valid in their recommendations [27]. Thus it is important to emphasize that clinical practitioners should critically evaluate the methodological quality as well as the content of the recommendations before adopting the recommendations, which leads to another issue, that is, consistency appraisal. Despite many researchers being aware of the crucial role of the appraisal of consistency between evidence and resulting recommendations, there are no existing criteria for assessing content consistency of guidelines. In guideline adaptation of some topics, qualitative analysis was used in content extraction, which formulated a general description of the research topic through generating categories without any consistency appraisal [31, 32]. In this review, we developed a “recommendation matrix” on the basis of the CAN-Implement© method [33], and used the tool to extract and assess guideline content. As a recommendation matrix was used, not only relevant and potentially relevant recommendations on all pre-specified healthcare aspects for GDM care were identified, but also consistency between search strategy and selection of evidence, between selected evidence and interpretation, and between interpretation and resulting recommendations was assessed. The results showed that current guidelines on GDM care are of varied consistency, and guidelines developed in internationally recognized guideline development methodology show better consistency. Also guidelines that have low consistency in one aspect may also have low consistency in other two aspects. This is probably because reporting quality of guidelines is the cornerstone of consistency assessment. Those guidelines with evidence tables or technical reports not published may also show low consistency. Thus, guideline development committees are strongly encouraged to make use of guideline development manuals when drafting guidelines.

Regarding guideline content, five aspects were analyzed: diagnosis of GDM, prenatal care, intrapartum care, neonatal care, and postpartum care. Most recommendations in guidelines focused on prenatal care, especially all kinds of therapies that might reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes related to uncontrolled blood sugar pre-conception. This review generated similar results with those from a previous study that international guidelines were consistent in most of their recommendations [34]. Nonetheless, although commonality in most areas existed, there were still some discrepancies among guidelines. For example, recommendations regarding oral hypoglycemic agents in the guidelines diverged. Some guidelines recommended that oral hypoglycemic agents be considered as an initial pharmacological intervention, while some guidelines only considered insulin as an exclusive hypoglycemic medicine. Guidelines were supported with evidence, so inconsistency may be caused by insufficient evidence on pharmacological interventions in the period in which the guidelines were developed [26]. However, it should be reminded that even though all evidence available was identified, consensus usually did not warrant similar recommendations in different contexts. This was because when a recommendation was developed, not only available evidence, but benefits and harms, patients’ values and preferences, as well as resource implications, should be appropriate considered [10].

Since recommendations were well summarized, guideline adaptation was required to maintain the validity of recommendations in different health care systems. Guideline adaptation involves using knowledge synthesis of existing guidelines to produce recommendations, rather than relying only on a review of primary literature, for the purpose of reducing duplication of effort [35]. In mainland China and Hong Kong, there were only expert consensus for GDM care [22, 23], without a national GDM management evidence-based guideline adapted to the Chinese context previously. In this instance, it is recommended to adapt the clinical practice guideline related to GDM management for the local context, providing support for professionals to make better decisions in clinical practice. How to select, tailor and implement recommendations and supporting evidence extracted is the next challenging step.

Limitation

Due to the language barriers, we only included guidelines in English and Chinese. As a result, we only got existing guidelines on the management for GDM in 11 countries or regions in this review. And yet, we have no idea whether other countries use the recommendations provided by a certain guideline or use recommendations developed in their own language.

Another key limitation of this study is the subjectivity in appraising the consistency between evidence and recommendations. Although we attempted to minimize these discrepancies by stating the assessment criteria and through rigorous discussion, the results of the consistency appraisal still varied because of different understandings between researchers. Additionally, reporting quality of some guidelines is not clear cut, which was another barrier in the process of content analysis. Apart from this, this is the first time that we used a “recommendation matrix” in content analysis, and the tool we developed may still need to be modified.

Conclusion

This paper describes the process used to extract and access the content of guidelines for GDM management. In conclusion, the recommendations were developed in five aspects: diagnosis of GDM, prenatal care, intrapartum care, neonatal care and postpartum care. The consistency of guidelines on the management of GDM in pregnancy is highly variable and this inconsistency needs to be addressed. Also, this review has proven that a “recommendation matrix” can be a tool to extract and assess consistency of guidelines. Additionally, our findings indicated that it is necessary to adapt and disseminate easily understandable evidence-based guidelines based on knowledge synthesis of existing guidelines in this paper.

Abbreviations

- A.N.D:

-

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

- ADA:

-

American Diabetes Association

- API:

-

The Association of Physicians of India

- CDA:

-

Canadian Diabetes Association

- CMA:

-

Chinese Medical Association

- DDG:

-

German Diabetes Association

- DGGG:

-

German Gynecology and Obstetrics Association

- FIGO:

-

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- HKCOG:

-

The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

- IDF:

-

International Diabetes Federation

- NCC-WCH:

-

National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health

- NGC:

-

National Guideline Clearinghouse

- NICE:

-

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NZGG:

-

New Zealand Guidelines Group

- SIGN:

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of Hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Wu L, Han L, Zhan Y, Cui L, Chen W, Ma L, Lv J, Pan R, Zhao D, Xiao Z. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and associated risk factors in pregnant Chinese women: a cross-sectional study in Huangdao, Qingdao, China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2018;27(2):383–8.

Catalano PM, McIntyre HD, Cruickshank JK, McCance DR, Dyer AR, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Trimble ER, Coustan DR, Hadden DR, et al. The hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome study: associations of GDM and obesity with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):780–6.

Ovesen PG, Jensen DM, Damm P, Rasmussen S, Kesmodel US. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes. A nation-wide study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(14):1720–4.

Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):e290–6.

West NA, Crume TL, Maligie MA, Dabelea D. Cardiovascular risk factors in children exposed to maternal diabetes in utero. Diabetologia. 2011;54(3):504–7.

Hartling L, Dryden DM, Guthrie A, Muise M, Vandermeer B, Donovan L. Benefits and harms of treating gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. preventive services task force and the National Institutes of Health Office of medical applications of research. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):123–9.

Nisreen A, Derek JT, Jane W. Treatments for gestational diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003395.pub2.

Feng R, Liu L, Zhang YY, Yuan ZS, Gao L, Zuo CT. Unsatisfactory glucose management and adverse pregnancy outcomes of gestational diabetes mellitus in the real world of clinical practice: a retrospective study. Chin Med J. 2018;131(9):1079–85.

World Health Organization: WHO handbook for guideline development. 2012. Accessed 2018.

Academy Of Nutrition And Dietetics. Academy of nutrition and dietetics gestational diabetes mellitus evidence-based nutrition practice guideline. Chicago: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2016.

Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Clinical practice guidelines: diabetes and pregnancy. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37:S168–83.

Endocrine Society. Diabetes and pregnancy: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4227–49.

IDF Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Global Guideline on Pregnancy and Diabetes. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2009.

Ministry Of Health. Screening, Diagnosis and Management of Gestational Diabetes in New Zealand: A clinical practice guideline. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2014.

Queensland Health. Queensland Clinical Guideline: Gestational diabetes mellitus Guideline. Queensland: Queensland Health; 2015. Accessed 2018.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: Managemenet of diabetes: a national clinical guideline. 2013. Accessed 2018.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). Initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: a pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131(S3):S173–211.

Seshiah V, Banerjee S, Balaji V, Muruganathan A, Das AK. Consensus evidence-based guidelines for management of gestational diabetes mellitus in India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62(7 Suppl):55–62.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical Care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(suppl.1):s1–s159.

National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health: Diabetes in pregnancy: Management of diabetes and its complications from preconception to the postnatal period. 2015.Accessed 2018.

The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Guidelines for the Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. 2016. Accessed in http://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/Download/Guidelines_on_GDM_updated.pdf.

The Chinese medical association branch of obstetrics and gynaecology obstetric group. Diagnosis and management of diabetes in pregnancy: a clinical practice guideline (2014). Chin J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;49(8):561–9.

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7182):527–30.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Cluzeau F, feder G, Fervers B, Hanna S, Makarski J. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182(18):E839–42.

Greuter MJ, van Emmerik NM, Wouters MG, van Tulder MW. Quality of guidelines on the management of diabetes in pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:58.

Watine J, Friedberg B, Nagy E, Onody R, Oosterhuis W, Bunting PS, Charet JC, Horvath AR. Conflict between guideline methodologic quality and recommendation validity: a potential problem for practitioners. Clin Chem. 2006;52(1):65–72.

The ADAPTE Collaboration: Guideline adaption: a resource toolkit. 2010. Accessed 2018.

Schafer-Graf UM, Gembruch U, Kainer F, Groten T, Hummel S, Hosli I, Grieshop M, Kaltheuner M, Buhrer C, Kautzky-Willer A, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) - diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Guideline of the DDG and DGGG (S3 level, AWMF registry number 057/008, February 2018). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2018;78(12):1219–31.

Wang Y, Jin Y, Chen Y, Ceng X, Chen H, Wang L, Lu C, Cao H. The methodology of recommendations in evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2017;09:1085–92.

Hu Y, Cheng Y. Content analysis of existing clinical practice guidelines related to nasogastric feeding in adult patients. Chin J Nurs. 2014;49(10):1177–83.

Yu L, Hu J, Hao G, Ruan H. Content analysis of international clinical practice guidelines related to endotracheal suctioning of adults with an Artifcial airway. West Chin Med J. 2014;29(10):1922–6.

Harrison MB, van den Hoek J. CAN-IMPLEMENT: Guideline Adaptation and Implementation Planning Resource; 2012.

Mahmud M, Mazza D. Preconception care of women with diabetes: a review of current guideline recommendations. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:5.

Selby P, Hunter K, Rogers J, Lang-Robertson K, Soklaridis S, Chow V, Tremblay M, Koubanioudakis D, Dragonetti R, Hussain S, et al. How to adapt existing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: a case example with smoking cessation guidelines in Canada. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e16124.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Siew Siang Tay for helping us to revise the final version of the article.

Funding

This study was undertaken under grant 2016 Project of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and family Planning (No:201640324), and grant 2015 Nursing Research Project of Fudan University (No:FNF201502). The funders had no involvement in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions and gave final approval of the conceptions, drafting, and final version of this manuscript. The authors’ contributions are presented by their initials. MZ contributed to the data collection, review of the guidelines, and content extraction and the writing of this manuscript. YZ contributed to the data collection, review of the guidelines, and content extraction and the writing of this manuscript. JZ participated in the review of the guidelines, and helped to translate the recommendations. She also participated in the interpretation of data. KW participated in the review and translation of the guidelines. LL and YD participated in the recommendation appraisal, and helped to develop the “recommendation matrix” tool. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Recommendations Extraction of NICE guideline. The NICE guideline was developed in accordance with the NICE guideline development process. There were 74 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 1. (XLSX 24 kb)

Additional file 2:

Recommendations Extraction of NZGG guideline. The NZGG guideline development team followed a structured process for guideline development, and there were 38 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 2. (XLSX 19 kb)

Additional file 3:

Recommendations Extraction of SIGN guideline. The SIGN guideline was developed using a standard methodology according to SIGN guideline manual. There were 18 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 3. (XLSX 16 kb)

Additional file 4:

Recommendations Extraction of ADA guideline. The ADA guideline was developed using a standard methodology by the ADA’s Professional Practice Committee. The guideline included general recommendations about all kinds of diabetes, and there were only 17 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 4. (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 5:

Recommendations Extraction of FIGO guideline. The FIGO brought together international experts to develop the guideline, and suggestions are provided for a variety of different regional and resource settings. There were 40 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 5. (XLSX 19 kb)

Additional File 6:

Recommendations Extraction of Endocrine Society guideline. The Endocrine Society guideline was searched on the NGC website, which provided recommendations for the management of the pregnant woman with diabetes. Twenty-five relevant recommendations were extracted and appraised, which were displayed in Additional file 6. (XLSX 16 kb)

Additional file 7:

Recommendations Extraction of CDA guideline. The CDA guideline was developed following the process used to develop previous Canadian Diabetes Association clinical practice guidelines, and AGREE II were incorporated into the guideline development process. There were 17 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 7. (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 8:

Recommendations Extraction of API guideline. To develop API guideline, existing guidelines, meta-analyses, cross sectional studies, systematic reviews and key cited articles were reviewed, and the recommendations were discussed at the national insulin summit. There were 22 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 8. (XLSX 17 kb)

Additional file 9:

Recommendations Extraction of IDF guideline. The guideline was developed through a non-formal evidence review and discussed by a small Writing Group. There were 13 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 9. (XLSX 14 kb)

Additional file 10:

Recommendations Extraction of Queensland guideline. The Queensland guideline was developed based on evidence, and there were 8 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 10. (XLSX 14 kb)

Additional file 11:

Recommendations Extraction of HKCOG guideline. The HKCOG guideline was an expert consensus. It was updated taking reference to the recent evidence, WHO, NICE guideline and recommendations of other international bodies. There were 13 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 11. (XLSX 14 kb)

Additional file 12:

Recommendations Extraction of A.N.D. guideline. The guideline focused on nutrition practiece during the treatment of women with GDM. There were 15 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 12. (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 13:

Recommendations Extraction of DDG guideline. The recommendations of DDG guideline were based on the evidence from the literature, which was selected through a systematic external literature search. There were 21 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 13. (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 14:

Recommendations Extraction of CMA guideline. The CMA guideline was an expert consensus. There were 40 relevant recommendations being extracted, which were displayed and appraised in Additional file 14. (XLSX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Zhou, Y., Zhong, J. et al. Current guidelines on the management of gestational diabetes mellitus: a content analysis and appraisal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 200 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2343-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2343-2