Abstract

Background

The rates of cesarean section (CS) are increasing worldwide leading to an increased risk for maternal and neonatal complications in the subsequent pregnancy and labor. Previous studies have demonstrated that successful trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) is associated with the least maternal morbidity, but the risks of unsuccessful TOLAC exceed the risks of scheduled repeat CS. However, prediction of successful TOLAC is difficult, and only limited data on TOLAC in women with previous failed labor induction or labor dystocia exists. Our aim was to evaluate the success of TOLAC in women with a history of failed labor induction or labor dystocia, to compare the delivery outcomes according to stage of labor at time of previous CS, and to assess the risk factors for recurrent failed labor induction or labor dystocia.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study of 660 women with a prior CS for failed labor induction or labor dystocia undergoing TOLAC was carried out in Helsinki University Hospital, Finland, between 2013 and 2015. Data on the study population was obtained from the hospital database and analyzed using SPSS.

Results

The rate of vaginal delivery was 72.9% and the rate of repeat CS for failed induction or labor dystocia was 17.7%. The rate of successful TOLAC was 75.6% in women with a history of labor arrest in the first stage of labor, 73.1% in women with a history of labor arrest in the second stage of labor, and 59.0% in women with previous failed induction. The adjusted risk factors for recurrent failed induction or labor dystocia were maternal height < 160 cm (OR 1.9 95% CI 1.1–3.1), no prior vaginal delivery (OR 8.3 95% CI 3.5–19.8), type 1 or gestational diabetes (OR 1.8 95% CI 1.0–3.0), IOL for suspected non-diabetic fetal macrosomia (OR 10.8 95% CI 2.1–55.9) and birthweight ≥4500 g (OR 3.3 95% CI 1.3–7.9).

Conclusions

TOLAC is a feasible option to scheduled repeat CS in women with a history of failed induction or labor dystocia. However, women with no previous vaginal delivery, maternal height < 160 cm, diabetes or suspected neonatal macrosomia (≥4500 g) may be at increased risk for failed TOLAC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The rates of cesarean section (CS) are increasing worldwide. In Finland, the rate of CS is 16% of all births, and 20% in primiparous women, being the lowest figures among the western countries [1]. Since CS leads to an increased risk for abnormally attached placenta, uterine rupture, and maternal and neonatal complications in the subsequent pregnancy and labor [2], an abundance of research has been conducted to assess the feasibility and safety of trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) [3, 4].

Previous studies suggest that the mode of delivery with the least maternal morbidity for a woman with a history of prior low transverse CS is successful TOLAC [5,6,7], but the risks of unsuccessful TOLAC are higher than the risks of scheduled repeat CS [6]. However, prediction of successful TOLAC is difficult. TOLAC is suggested to be cost-effective compared to a repeat planned CS [8], and when considering long-term consequences, TOLAC with a success rate of 47% or more appears more economical than a repeat planned CS [9].

As shown by previous studies, the indication of the previous CS influences the success rate of TOLAC. Women with a previous CS for labor dystocia (non-progressing labor) have a lower rate of successful TOLAC compared to women with a nonrecurring CS indication such as breech presentation or fetal distress [10, 11]. The greatest predictor for successful TOLAC is a prior vaginal delivery [4, 12]. Prelabor nomograms have been presented to predict successful TOLAC [13, 14], but the data on induction of labor (IOL) in women with a history of previous CS for failed induction or labor dystocia is limited [15].

Our primary aim was to evaluate the success of TOLAC, including IOL, in this subgroup of women, and to compare delivery outcomes according to stage of labor at time of the previous CS. We also wanted to assess risk factors for repeat CS for recurrent failed labor induction or labor dystocia.

Methods

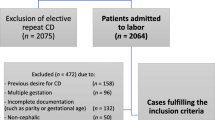

This retrospective cohort study of women with a history of previous emergency CS for labor dystocia or failed labor induction was carried out in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Helsinki University Hospital, Finland. All women with a vital singleton term pregnancy, cephalic presentation, and previous lower segment transverse CS for failed labor induction or labor dystocia undergoing TOLAC between January 1st 2013 and January 1st 2015 were identified in the hospital database. Women with scheduled repeat CS, preterm delivery, breech presentation, twin pregnancy or fetal demise were excluded (Fig. 1). Women undergoing IOL and women with spontaneous onset of labor were both included in the study (Fig. 1). The study protocol was approved by the management of Hospital district of Helsinki and Uusimaa. An informed consent was not required since this was a retrospective cohort study approved by the hospital management.

Data on the study population characteristics and labor and delivery outcomes were obtained from individual patient charts in the hospital database.

Gestational age was determined by the crown-rump-length measurement at the time of the first trimester ultrasound screening. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥35 kg/m2, and gestational diabetes was diagnosed by a 2-h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test. Medication-dependent gestational diabetes included both insulin and metformin treatments. Post-term pregnancy was defined as gestational age ≥ 42+ 0 weeks. Fetal macrosomia was defined by birthweight ≥4500 g. In case of term premature rupture of membranes (PROM), labor was induced after 24 h of expectant management.

The indications for labor induction were categorized as post-term pregnancy, PROM, gestational diabetes, suspected non-diabetic fetal macrosomia, fetal reason and maternal reason. Fetal reason for labor induction included oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, nonreassuring cardiotocograph, intrauterine growth restriction, Rh-immunization, reduced fetal movements, prevention of fetal malposition after successful external cephalic version, and gastrointestinal anomalies. Maternal reason for labor induction included pre-eclampsia, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, maternal medical condition, exhaustion, psychosocial reasons, and complications in an earlier pregnancy such as previous intrauterine death or shoulder dystocia.

Labor induction was carried out by artificial rupture of membranes (amniotomy) and oxytocin in case of a favorable cervix (Bishop score ≥ 6). In case of an unfavorable cervix, a single 50 ml Foley catheter (FC, Rüsh 2-way Foley, Couvelaire tip, catheter size 22Ch, Teleflex Medical, Athlone, Ireland) or misoprostol (Cytotec, Piramal Healthcare UK Limited, Northumberland, England) were used for cervical ripening. FC was retained for a maximum of 24 h. Misoprostol was administered 50 μg orally or 25 μg vaginally every 4 h until Bishop score ≥ 6 was achieved. Amniotomy was performed when the cervix was favorable, and oxytocin was started after 2–12 h if contractions deemed inadequate. Continuous fetal cardiotocography was routinely used during labor.

Failed labor induction was defined as failure to progress in the setting of ruptured membranes, oxytocin infusion for ≥12 h, and cervical dilation < 6 cm [16]. Labor dystocia in the first stage of labor was defined as failure to progress at cervical dilation ≥6 cm with ruptured membranes and adequate contractions for a minimum of 4 h [16]. Labor dystocia in the second stage of labor was defined as failure to deliver at cervical dilation of 10 cm despite of ≥1 h of active pushing or failed operative vaginal delivery [16].

The primary outcomes were the rate of repeat CS and the rate of recurring failed labor induction or labor dystocia. The secondary outcomes were the rates of uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage ≥1000 ml, maternal intrapartum and postpartum infections, and adverse neonatal primary outcome [17, 18].

Adverse neonatal primary outcome was defined as a 5-min Apgar-score < 7, umbilical artery blood pH-value < 7.05, or base excess (BE) value <− 12 [17, 18]. Uterine rupture was defined as a complete rupture of both myometrium and visceral peritoneum. Intrapartum infection was defined as fever ≥38 °C, fetal tachycardia, and total white cell count ≥20 e9/l. Postpartum infection included endometritis (defined as fever ≥38 °C, total white cell count ≥20 e9/l, uterine tenderness, and purulent vaginal discharge), clinical wound infection, and urinary tract infection verified by a positive finding in urine culture.

Statistical analysis was performed by using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (Armonk, NY, USA). Data with categorical variables were compared by Pearson’s Chi-square test. Unpaired comparisons of continuous variables were carried out by Student’s t-test when the data were normally distributed. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess relative risks for unsuccessful TOLAC and recurrent CS for failed labor induction or labor dystocia. Adjusted odd ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by modelling the data to control for possible confounding factors. All variables used in the multivariate analyses are shown in the tables with respective univariate analyses. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 660 women with a prior CS for failed labor induction or labor dystocia were included. Of the women, 226 (34.2%) underwent IOL and 434 (65.8%) women had spontaneous onset of labor. A total of 481 women (72.9%) had successful TOLAC. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population. The women with unsuccessful TOLAC were shorter, more obese, more often had post-term pregnancy, diabetes, no prior vaginal delivery, and more often underwent IOL (Table 1). A total of 519 women (78.6%) had no prior vaginal delivery, 26 women (3.9%) had delivered vaginally prior to the CS, 106 women (16.1%) had delivered vaginally after the CS, and nine women (1.4%) had prior vaginal delivery both prior to and after the CS. The most common indication for IOL in the current pregnancy was post-term pregnancy (n = 65, 28.8%) (Table 1). FC was used as the primary method for IOL in 135 (59.7%) women, misoprostol in 20 (8.8%) women, and amniotomy and oxytocin in 71 (31.4%) women.

The delivery outcomes are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Four cases (0.6%) of uterine rupture occurred (Tables 2 and 3), all in women with no prior vaginal delivery. Three of the uterine ruptures occurred following spontaneous onset of labor and one case occurred following amniotomy and oxytocin induction. There were no cases of hysterectomy. The overall rate of maternal intrapartum infection was 2.9% and postpartum infection 2.4% (Tables 2 and 3). Intrapartum infections and postpartum hemorrhage more often occurred following unsuccessful TOLAC compared to successful TOLAC (Table 2). The rates of oxytocin use (92.9% vs. 89.9%, p = 0.21) and epidural or spinal analgesia (86.3% vs. 89.4%, p = 0.29) were similar. No significant difference in the rates of adverse primary neonatal outcomes was seen between the groups (Tables 2 and 3). Seventeen (2.6%) neonates had an umbilical artery blood pH < 7.05 at birth, and 26 (3.9%) had a 5-min Apgar score < 7.

The rate of successful TOLAC was 75.6% in women with a history of labor arrest in the first stage of labor, 73.1% in women with a history of labor arrest in the second stage of labor, and 59.0% in women with a history of failed labor induction (Table 3). The overall rate of recurring failed labor induction or labor dystocia leading to repeat CS was 17.7%, being 15.9% in women with a history of labor arrest in the first stage of labor, 17.3% in women with a history of labor arrest in the second stage of labor, and 27.0% in women with a history of failed labor induction (p = 0.01) (Table 3). Infections were more common in the subgroup of women with previous failed labor induction (Table 3). Seventy-seven women with a history of failed labor induction underwent IOL also in the current pregnancy (Table 3). Of these, 40 women (51.9%) had a successful TOLAC, 26 women (33.8%) had repeat CS for labor dystocia, and 18 (23.4%) women had recurrent failed IOL.

The risk factors for unsuccessful TOLAC are presented in Table 4, and the risk factors for recurring failed labor induction or labor dystocia are presented in Table 5. After adjustment, maternal height < 160 cm (OR 1.9), no prior vaginal delivery (OR 8.3), type 1 or gestational diabetes (OR 1.8), IOL for suspected non-diabetic fetal macrosomia (OR 10.8) and birthweight ≥4500 g (OR 3.3) remained significant risk factors for recurrent failed induction or labor dystocia and repeat CS (Table 5). In the subgroup of women with a history of previous failed labor induction, the adjusted risk factors for recurrent failed labor induction or labor dystocia were smoking (OR 10.5), BMI ≥35 (OR 5.3), and induction of labor for reasons other than PROM or diabetes (Table 6).

Discussion

Our results show a relatively high success rate of 73% for TOLAC in women with a history of previous failed labor induction or labor dystocia. Lower vaginal delivery rates of 49–68% following TOLAC for non-progressive labor have previously been reported [11, 12, 15, 19,20,21,22,23]. Our results suggest that the highest rate of repeat CS occurs in women with a history of failed labor induction compared to women with labor dystocia in the first or second stage of labor. Furthermore, every fifth woman with a history of failed labor induction had recurring failed IOL.

The greatest predictor for successful TOLAC is a prior vaginal delivery [4], as also seen in our study. However, two thirds of the women with no prior vaginal delivery in our study also had successful TOLAC. Women undergoing IOL had lower success rate of TOLAC compared to women with spontaneous onset of labor, as reported previously [11, 24]. Increasing maternal age and BMI may propose a greater risk for CS [4, 25,26,27,28]. In this study, maternal age ≥ 37 years was associated with repeat CS, and BMI ≥ 35 was associated with recurring failed labor induction or labor dystocia in the subgroup of women with a history of induction failure. In our study, maternal height < 160 cm was associated with an increased risk for repeat CS. This is in line with previous studies suggesting that shorter maternal stature appears an independent risk factor for induction failure, and taller women are more likely to have a vaginal delivery [29, 30]. Also, increasing neonatal birth weight > 4000 g has been shown to increase the risk for a recurrent CS [31,32,33], which is in agreement with our results.

The overall rate of uterine rupture was low (0.6%) in our study. Higher rates of uterine rupture have been reported following IOL compared to spontaneous onset of labor [24, 34,35,36], while contradictive results have also been presented [37]. In our study, three of the four uterine ruptures occurred following spontaneous onset of labor. The women with uterine rupture had no prior vaginal delivery, which may increase the risk for uterine rupture [34]. The method of choice for IOL in women with an unfavorable cervix and a history of previous CS is FC [38, 39]. Some women in our study received misoprostol for IOL despite of the uterine scar, even though this is not supported by our clinical guidelines. However, no uterine ruptures occurred in these women.

The rate of postpartum hemorrhage in our study was higher than previously reported [40, 41]. Increased post-partum hemorrhage more often occurred following unsuccessful TOLAC, as also previously reported [24]. The rates of maternal infections were also consistent with previous studies [5, 34, 40]. Higher rate of maternal morbidity and endometritis have been shown to occur in women with an unsuccessful TOLAC compared to women with a successful TOLAC [5], and a similar trend was seen also in our study. Adverse neonatal primary outcomes were not frequent following TOLAC, which is in line with previous studies [23, 40].

The strengths of our study were the relatively large sample size, the systematic and detailed medical records, and standardized labor management protocol in our hospital. The major weaknesses of this study are the retrospective design and not including the women delivering by a planned CS, which may have caused a potential bias. Also, this study may have lacked power to detect possible associations between several important variables. We regret not having the data on estimated fetal weight available in our study, but as a surrogate, we used birthweight. A previous study indicated that a 500 g increase in birthweight in current pregnancy, compared to the pregnancy with labor dystocia, decreases the rate of a successful TOLAC [27]. Furthermore, unfortunately we did not have the data on cervical dilation at the previous CS, as cervical dilation of 7 cm or more has been suggested to increase the likelihood of successful TOL in the subsequent pregnancy [12, 21, 22].

Conclusions

TOLAC, including both spontaneous and induced labor, is a feasible option for scheduled repeat CS in women with a history of previous failed labor induction or labor dystocia. However, our results suggest that women with no previous vaginal delivery, maternal height < 160 cm, diabetes, and suspected neonatal macrosomia (≥4500 g) may be at increased risk for failed trial of labor. Also, BMI ≥35, smoking, no prior vaginal delivery and induction of labor for reasons other than PROM may be associated with recurring failed induction or labor dystocia.

Abbreviations

- CS:

-

Cesarean section

- IOL:

-

Induction of labor

- PROM:

-

Premature rupture of membranes

- TOLAC:

-

Trial of labor after cesarean

References

OECD Data on cesarean sections [https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/caesarean-sections.htm] Accessed 31 Aug 2018.

Silver RM. Implications of the first cesarean: perinatal and future reproductive health and subsequent cesareans, placentation issues, uterine rupture risk, morbidity, and mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36(5):315–23.

Grivell RM, Barreto MP, Dodd JM. The influence of intrapartum factors on risk of uterine rupture and successful vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38(2):265–75.

Landon MB, Grobman WA, Kennedy E. Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development maternal-fetal medicine units network: what we have learned about trial of labor after cesarean delivery from the maternal-fetal medicine units cesarean registry. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40(5):281–6.

Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker S, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, Carpenter M, Peaceman AM, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai B, Langer O, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM, Gabbe SG. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development maternal-fetal medicine units network: maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2581–9.

Rossi AC, D'Addario V. Maternal morbidity following a trial of labor after cesarean section vs elective repeat cesarean delivery: a systematic review with metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):224–31.

Shanks AL, Cahill AG. Delivery after prior cesarean: success rate and factors. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38(2):233–45.

Rogers AJ, Rogers NG, Kilgore ML, Subramaniam A, Harper LM. Economic evaluations comparing a trial of labor with an elective repeat cesarean delivery: a systematic review. Value Health. 2017;20(1):163–73.

Gilbert SA, Grobman WA, Landon MB, Spong CY, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Varner MW, Caritis SN, Meis PJ, Sorokin Y, Carpenter M, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM, Kennedy E. Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development maternal-fetal medicine units network: elective repeat cesarean delivery compared with spontaneous trial of labor after a prior cesarean delivery: a propensity score analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):311.e1–9.

Shipp TD, Zelop CM, Repke JT, Cohen A, Caughey AB, Lieberman E. Labor after previous cesarean: influence of prior indication and parity. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):913–6.

Landon MB, Leindecker S, Spong CY, Hauth JC, Bloom S, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, Carpenter M, Peaceman AM, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Langer O, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM, Gabbe SG. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development maternal-fetal medicine units network: the MFMU cesarean registry: factors affecting the success of trial of labor after previous cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 2):1016–23.

Abildgaard H, Ingerslev MD, Nickelsen C, Secher NJ. Cervical dilation at the time of cesarean section for dystocia -- effect on subsequent trial of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(2):193–7.

Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ, Rouse DJ, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, Carpenter M, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Langer O, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) maternal-fetal medicine units network (MFMU): development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):806–12.

Eden KB, McDonagh M, Denman MA, Marshall N, Emeis C, Fu R, Janik R, Walker M, Guise JM. New insights on vaginal birth after cesarean: can it be predicted? Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):967–81.

Mizrachi Y, Barber E, Kovo M, Bar J, Lurie S. Prediction of vaginal birth after one ceasarean delivery for non-progressive labor. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (College), Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(3):179–93.

Low JA. Intrapartum fetal asphyxia: definition, diagnosis, and classification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(5):957–9.

Yeh P, Emary K, Impey L. The relationship between umbilical cord arterial pH and serious adverse neonatal outcome: analysis of 51,519 consecutive validated samples. BJOG. 2012;119(7):824–31.

Maykin MM, Mularz AJ, Lee LK, Valderramos SG. Validation of a prediction model for vaginal birth after cesarean delivery reveals unexpected success in a diverse American population. AJP Rep. 2017;7(1):e31–8.

Peaceman AM, Gersnoviez R, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ, Varner MW, Rouse DJ, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, Carpenter M, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Langer O, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development maternal-fetal medicine units network: the MFMU cesarean registry: impact of fetal size on trial of labor success for patients with previous cesarean for dystocia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(4):1127–31.

Obeidat N, Meri ZB, Obeidat M, Khader Y, Al-Khateeb M, Zayed F, Alchalabi H, Kriesat W, Lataifeh I. Vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC) in women with spontaneous labour: predictors of success. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(5):474–8.

Lewkowitz AK, Nakagawa S, Thiet MP, Rosenstein MG. Effect of stage of initial labor dystocia on vaginal birth after cesarean success. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):861.e1–5.

Bujold E, Gauthier RJ. Should we allow a trial of labor after a previous cesarean for dystocia in the second stage of labor? Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(4):652–5.

Rossi AC, Prefumo F. Pregnancy outcomes of induced labor in women with previous cesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(2):273–80.

Srinivas SK, Stamilio DM, Sammel MD, Stevens EJ, Peipert JF, Odibo AO, Macones GA. Vaginal birth after caesarean delivery: does maternal age affect safety and success? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21(2):114–20.

Bujold E, Blackwell SC, Gauthier RJ. Cervical ripening with transcervical Foley catheter and the risk of uterine rupture. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):18–23.

Carroll CSS, Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Klauser CK, Morrison JC. Vaginal birth after cesarean section versus elective repeat cesarean delivery: weight-based outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(6):1516–20 discussion 1520-2.

Hibbard JU, Gilbert S, Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Varner MW, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, Carpenter M, Peaceman AM, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Langer O, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM, Gabbe SG. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development maternal-fetal medicine units network: trial of labor or repeat cesarean delivery in women with morbid obesity and previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):125–33.

Beckmann M. Predicting a failed induction. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(5):394–8.

Frederiks F, Lee S, Dekker G. Risk factors for failed induction in nulliparous women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(12):2479–87.

Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, Cohen A, Lieberman E. Outcomes of trial of labor following previous cesarean delivery among women with fetuses weighing >4000 g. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(4):903–5.

Elkousy MA, Sammel M, Stevens E, Peipert JF, Macones G. The effect of birth weight on vaginal birth after cesarean delivery success rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(3):824–30.

Kalok A, Zabil SA, Jamil MA, Lim PS, Shafiee MN, Kampan N, Shah SA. Mohamed Ismail NA: antenatal scoring system in predicting the success of planned vaginal birth following one previous caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017:1–5.

Grobman WA, Gilbert S, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ, Rouse DJ, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, Carpenter M, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Langer O, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM. Outcomes of induction of labor after one prior cesarean. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):262–9.

Lydon-Rochelle MT, Cahill AG, Spong CY. Birth after previous cesarean delivery: short-term maternal outcomes. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34(4):249–57.

Kehl S, Weiss C, Rath W. Balloon catheters for induction of labor at term after previous cesarean section: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;204:44–50.

Ashwal E, Hiersch L, Melamed N, Ben-Zion M, Brezovsky A, Wiznitzer A, Yogev Y. Pregnancy outcome after induction of labor in women with previous cesarean section. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(4):386–91.

West HM, Jozwiak M, Dodd JM. Methods of term labour induction for women with a previous caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD009792.

Sananes N, Rodriguez M, Stora C, Pinton A, Fritz G, Gaudineau A, Aissi G, Boudier E, Viville B, Favre R, Nisand I, Langer B. Efficacy and safety of labour induction in patients with a single previous caesarean section: a proposal for a clinical protocol. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(4):669–76.

Jozwiak M, van de Lest HA, Burger NB, Dijksterhuis MG, De Leeuw JW. Cervical ripening with Foley catheter for induction of labor after cesarean section: a cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(3):296–301.

Ten Eikelder ML, Oude Rengerink K, Jozwiak M, de Leeuw JW, de Graaf IM, van Pampus MG, Holswilder M, Oudijk MA, van Baaren GJ, Pernet PJ, Bax C, van Unnik GA, Martens G, Porath M, van Vliet H, Rijnders RJ, Feitsma AH, Roumen FJ, van Loon AJ, Versendaal H, Weinans MJ, Woiski M, van Beek E, Hermsen B, Mol BW, Bloemenkamp KW. Induction of labour at term with oral misoprostol versus a Foley catheter (PROBAAT-II): a multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1619–28.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hanna Wilkman, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Finland, for her collaboration in data gathering.

Funding

The authors declare no funding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to the design of this study. HK and LR were responsible for data gathering, and data analysis was performed by KP, HK and LR. Manuscript was drafted by KP, HK and LR. AT and SH contributed in the study design, reviewing the data and writing the manuscript. All authors have contributed in the revision of the study and gave approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa (Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District Ethics Committee for Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pediatrics and Psychiatry). The permission was collectively granted for all three hospitals (Women’s Hospital, Maternity Hospital and Jorvi Hospital) included in the study. All three hospitals belong to Helsinki University hospital as well as to the hospital district of Helsinki and Uusimaa. According to national regulations (Medical Research Act 488/1999, chapter 2 a (23.4.2004/295), section 5 and 10a) and the IRB of the Hospital district of Helsinki and Uusimaa, no informed consent was required since this was a retrospective cohort study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Place, K., Kruit, H., Tekay, A. et al. Success of trial of labor in women with a history of previous cesarean section for failed labor induction or labor dystocia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 176 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2334-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2334-3