Abstract

Background

Depressive symptoms negatively impact on breastfeeding duration, whereas early breastfeeding initiation after birth enhances the chances for a longer breastfeeding period. Our aim was to investigate the interplay between depressive symptoms during pregnancy and late initiation of the first breastfeeding session and their effect on exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum.

Methods

In a longitudinal study design, web-questionnaires including demographic data, breastfeeding information and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) were completed by 1217 women at pregnancy weeks 17–20, 32 and/or at six weeks postpartum. A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the effect of depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the timing of the first breastfeeding session on exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum.

Results

Exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum was reported by 77% of the women. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy (EPDS> 13); (OR:1.93 [1.28–2.91]) and not accomplishing the first breastfeeding session within two hours after birth (OR: 2.61 [1.80–3.78]), were both associated with not exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum after adjusting for identified confounders. Τhe combined exposure to depressive symptoms in pregnancy and late breastfeeding initiation was associated with an almost 4-fold increased odds of not exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum.

Conclusions

Women reporting depressive symptoms during pregnancy seem to be more vulnerable to the consequences of a postponed first breastfeeding session on exclusive breastfeeding duration. Consequently, women experiencing depressive symptoms may benefit from targeted breastfeeding support during the first hours after birth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breastfeeding is widely known to benefit both the baby and the mother [1, 2]. As several of the breastfeeding benefits for both mother and infant appear to be further strengthened by longer duration and exclusive breastfeeding, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months after birth [3]. The Swedish recommendations are in line with the WHO guidelines, although they include an amendment declaring that the introduction of “tiny sensations” of solid food from the age of four months is harmless if it does not affect continuous breastfeeding [4]. In general, breastfeeding rates are high among new mothers [5]. In 2014, 96% of Swedish mothers were breastfeeding one week after birth [5]. However, rates of exclusive breastfeeding are shown to be decreasing, especially towards the late postpartum period, being around 64% at two months, and plummeting to 16% at six months postpartum [5].

Several factors could affect the duration of breastfeeding. Specifically early breastfeeding initiation have been associated with longer exclusive breastfeeding duration, as well as a strengthened breastfeeding self-efficacy [6,7,8]. On the other hand, breastfeeding self-efficacy is not only associated with longer breastfeeding duration, but also with lower levels of depressive symptoms [9]. To enable an early breastfeeding session after birth, skin-to-skin care between mother and newborn seems to have several benefits [10]. Accordingly, recommendations suggest that breastfeeding should be initiated as soon as possible after birth [3] and the baby should be preferably placed with the mother and not separated until the first breastfeeding session takes place [11].

Depression is among the most common maternal complications during childbearing, with an estimated 20% of mothers experiencing an episode within the first three months postpartum. One of the strongest predictor for postpartum depression is the incidence of depression during pregnancy [12,13,14]. There is evidence demonstrating a complex interplay between perinatal depression and breastfeeding with a potentially amphi-directional association. A recent systematic review dealing with this issue concludes that depression during pregnancy predicts a shorter breastfeeding duration which may consequently increase postpartum depressive symptoms [15].

The aim of this study was to assess the interplay between antenatal depressive symptoms and early initiation of breastfeeding on exclusive breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum, when there is no obvious reason for introducing other foods or drinks, in a population-based cohort of Swedish pregnant women.

Methods

Study population

This study was undertaken as part of the BASIC (Biology, Affect, Stress, Imaging and Cognition) project, a population-based longitudinal study ongoing since September 2009, which included more than 4500 pregnancies and focuses on antenatal and postnatal maternal wellbeing; detailed information may be found elsewhere [16]. All pregnant women attending the routine ultrasound examination, in gestational week 17–20, at the Uppsala University Hospital, receive written information about the project and are invited to participate. Exclusion criteria at recruitment include inability to adequately communicate in Swedish, protected identity, pathologic pregnancies as diagnosed by the routine ultrasound or intrauterine demise and age < 18 years. Written consent was obtained from all the participating women. After obtaining consent, participating women are asked to complete self-administered web-based questionnaires at recruitment, at gestational week 32 and at six weeks postpartum. The BASIC project has a participation rate of 22% and the study protocol has been approved by the Regional Research and Ethics Committee of Uppsala (no. 2009/171). For the whole cohort, 81.3% of those giving consent to participate complete the questionnaire in gestational week 32 and for the whole cohort, 80.9% at 6 weeks postpartum.

The present study is a sub-study of the BASIC project, based on data collected from February, 2014, to June, 2016 (n = 1501 unique participants). Women, who gave birth before the 36th gestational week (n = 24), had missing values for gestational week at birth (n = 131), gave birth in another hospital (n = 8), did not initiate breastfeeding (n = 23), as well as mothers of twin pregnancies (n = 19) and repetitive participants due to a new pregnancy (n = 17) were excluded from the study. Women with missing values on breastfeeding duration (n = 5) or depressive symptoms during pregnancy (n = 63) were also excluded from this sub-study. Finally, 1217 women were included in the analyses (Fig. 1).

Outcome measures and study variables

In the present study, the main outcome was exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum, dichotomized into exclusive breastfeeding versus partial breastfeeding or cessation of breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum, as self-reported by the participants. Several background and antenatal sociodemographic, lifestyle and medical variables, such as age (< 25, 25–34, > 35 years), body mass index (BMI) before pregnancy (< 25, 25–29, 30–34, > 35 kg/m2), educational level (high school or lower vs college/university), smoking during pregnancy (yes vs no), medical history of depression (no history of depression vs history of depression), employment status (working/studying vs on maternity leave/sick/unemployed) were included in the first web-questionnaire, answered by the women at gestational week 17–20. Obstetric variables such as parity (primiparas vs multiparas), mode of delivery (vaginal birth, vacuum extraction, planned caesarean section, emergency caesarean section), use of local epidural anesthesia as well as obstetric complications in pregnancy (any of the following, as self-reported or reported in medical records; vaginal bleeding during pregnancy, significant Braxton-Hicks contractions, symphysiolysis, diabetes, hypothyroidism, hypertonia and preeclampsia) and postpartum complications (hemorrhage > 1000 ml, manual placental expulsion, Apgar score at 5 min < 7, admission to the neonatal unit, laceration grade III or IV) were obtained from the medical records. The questions on timing of the first breastfeeding session after birth, experience of the first breastfeeding session (very positive/positive vs negative/very negative) and use of the hands-on approach, i.e. when health care professionals force the baby to the breast by using their hands and touching the woman’s breast and the baby in order to stimulate latch-on and breastfeeding, during the first breastfeeding session (no vs yes) were answered by the women at six weeks postpartum. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy were determined by the Swedish version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at gestational week 17–20 and/or gestational week 32. In line with previous studies, a score of > 13, giving a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 94%, was considered indicative of presence of depressive symptoms [17]. EPDS was also used for evaluation of depressive symptoms in the postpartum periods and particularly at six weeks postpartum; a cut-off of ≥12, giving a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 49%, was used, as recommended for a Swedish sample [18].

Statistical analyses

Crude analyses were performed to assess the possible associations of the study variables with breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum. Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated through cross-tabulations. A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the specific effect of breastfeeding initiation later than two hours after birth and depressive symptoms during pregnancy on exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum. There was no multicollinearity between the variables included in the model. In order to identify potential mediators and confounders, we created a conceptual directly acycled graph (DAG), based on literature data and available variables (Additional file 1: Figure S1). According to the DAGs, a direct effect model (model 1) was designed including age, mode of giving birth, depressive symptoms during pregnancy, educational level and parity, as well as an indirect effect model (model 2) investigating also the mediators effect, which included age, mode of giving birth, history of depression, depressive symptoms during pregnancy, educational level, parity, use of the hands-on approach during the first breastfeeding session and experience of the first breastfeeding session. The analysis was thereafter repeated stratified by the mode of giving birth.

To additionally explore the interplay between depressive symptoms during pregnancy and breastfeeding initiation later than two hours after birth, a composite variable was created and multivariate associations with the outcome variable were investigated. The composite variable included the following categories: (a) women with no depressive symptoms during pregnancy who initiated breastfeeding within two hours after birth (set as the reference category), (b) women with no depressive symptoms during pregnancy who initiated breastfeeding more than two hours after birth, (c) women with depressive symptoms during pregnancy who initiated breastfeeding within two hours after birth, (d) women with depressive symptoms during pregnancy who initiated breastfeeding > two hours after birth.

SPSS version 24 was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

In total, 1217 women were included in the current study (Fig. 1). The mean age of the participating women was 31.4 (SD: 4.5) years and 47% of them were primiparas. Among the women who breastfed for the first time within two hours as well as the women breastfeeding for the first time after two hours, the mean age was 31.0 (SD: 4.5). Education of college or university level was reported by 80% of the participants and 92% were employed or studying. Among women, breastfeeding for the first time within 2 h after birth, the mean BMI was 24 (SD: 4.0). Among women, breastfeeding for the first time after two hours postpartum, the mean BMI was 24 (SD: 4.8). Only 7 and 1% of the women had a BMI in the spectrum 30–34.9 and ≥ 35 kg/m2 before pregnancy, respectively, whereas the proportion of those smoking during pregnancy was below 1 %. Seventy-nine percent of the women gave birth vaginally. Regarding the main variables of interest, the prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy was 13%. Notably, 78% of the women reported initiation of breastfeeding within two hours after birth and 77% reported breastfeeding exclusively at six weeks postpartum. As presented in Table 1, the univariate analyses showed increased odds of delayed (> 2 h) breastfeeding initiation with primiparity, BMI ≥35, planned or emergency caesarean section and vacuum extraction, use of local epidural anesthesia during labour and postpartum obstetric complications. Furthermore, initiation of breastfeeding > two hours after birth was associated with a negative experience of the first breastfeeding session and experience of the hands-on approach during the first breastfeeding session.

Table 2 presents the distribution of the study variables by exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum and the univariate effects of associations. Background factors that were associated with increased odds for not exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks were age < 25 years, primiparity, low education, being unemployed and increasing BMI. On the other hand, women with a history of depression were less likely to breastfeed exclusively at six weeks postpartum. Regarding pregnancy variables, pregnancy complications, presence of depressive symptoms in pregnancy and caesarean section were also associated with not breastfeeding exclusively at six weeks postpartum. During the first breastfeeding session, a delayed initiation (> 2 h) of breastfeeding, a self-reported negative experience and experience of the hands-on approach were negative predictors of exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum. Noteworthy was the fact that women reporting depressive symptoms at six weeks postpartum were also more likely to report partial breastfeeding or cessation of breastfeeding.

The multivariable logistic regression analysis for exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum is displayed in Table 3. According to the direct effect model (Model 1), both the presence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy (OR:1.93, 95% CI: 1.28–2.91) and not initiating breastfeeding within the first two hours after birth (OR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.80–3.78) were independent significant predictors for not exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum. Among other variables included in the model, primiparas, women with lower educational level, and women giving birth by planned caesarean section compared to vaginal birth, were at increased odds of not exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum.

The indirect effect model, investigating also the effect of the mediators in the odds of not exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum is also presented in Table 3 (Model 2). The association of depressive symptoms in pregnancy and initiation of breastfeeding later than six hours after birth, but also of lower education and planned caesarean section with not breastfeeding exclusively at six weeks postpartum remained in this model, but the effect of parity was lost. Additionally, the use of the hands-on approach in the first breastfeeding session, a negative first breastfeeding experience and a history of depression before pregnancy were associated with not exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum.

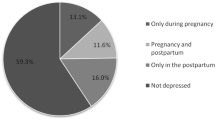

When combining the two main exposure variables of interest (depressive symptoms during pregnancy and breastfeeding initiation within two hours after birth), as depicted in Fig. 2, women with depressive symptomatology who did not breastfeed within the first two hours after birth were at the highest risk for not breastfeeding exclusively at six weeks postpartum. Notably though, both variables, even on their own, significantly increased the odds. A power calculation based on our sample size showed that the sample was sufficiently powered (1-β > 80%) to detect as statistically significant (α = 0.05) a minimum OR of 1.59, as an association estimate between breastfeeding initiation later than two hours after birth and not exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum.

Multiple logistic regression analysis derived Odds Ratios (OR) and their 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) on the combined effect of depressive symptoms during pregnancy and breastfeeding or not within two hours after birth on the odds of exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum. The ORs are adjusted for mother’s age when giving birth, parity, educational level, mode of birth, history of depression, hands-on approach, and breastfeeding experience

Discussion

Main findings

The current study identified a cumulative negative effect of the presence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy and a postponed first breastfeeding session on the duration of exclusive breastfeeding as assessed at six weeks postpartum. This indicates that women with depressive symptoms during pregnancy might be more vulnerable to the consequences of a postponed first breastfeeding session on breastfeeding later in the postpartum period.

Strengths and limitations

Among the main strengths of this study are the large sample size and the number of studied variables on an individual level, which gave the possibility of controlling for multiple confounders in the analyses. On the negative side, it could be argued that women answered questions on breastfeeding initiation via self-report at six weeks postpartum, which poses an eventual problem of recall bias. Nevertheless, it has been shown that women a long time after giving birth, are capable of successfully recalling what happened during the birth process and the early hours postpartum [19]. Additionally, intention to breastfeed was not assessed in the questionnaires, as we assume that nearly all mothers in this Swedish setting had planned to breastfeed; indeed, all women included in the study actually initiated breastfeeding. Nevertheless, one could speculate that some women who delayed the breastfeeding initiation might have a lower commitment to breastfeeding, which could be reflected in not exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum. To be considered is also the fact that, women participating in the present study have a higher exclusive breastfeeding rate compared to the Swedish national and county-level average. Overall, the BASIC study has a participation rate of 22% pregnant women, probably due to extensive questionnaires and collection of biological material. The participating women have a slightly higher educational level than the background population in Uppsala and are slightly more often primiparas. These differences could affect the generalizability of the findings but they are not expected to greatly affect effect estimates. Further, the prevalence of perinatal depression in the BASIC study is very close to that of other studies, hence the lack of an attrition analysis should not introduce significant bias in our analyses. Lastly, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, although widely recognized in medical research and also translated and validated in Swedish, [17] only detects depressive symptoms and does not provide a diagnosis of clinical depression.

Interpretation

In our sample, one fifth of the mother-infant dyads did not have the opportunity to accomplish the first breastfeeding session within two hours after birth, despite the recommendations to initiate breastfeeding during the newborns’ initial alert period during the first hours after birth. This could be due to separation of mother and newborn after a caesarean section or another complication. At the Uppsala University Hospital, all infants being born by caesarean section are to be removed from the operating theatre and separated from the mother, for a short time period. If a midwife or nurse is not available to take responsibility for the infant in the recovery ward, the infant will continue to be separated from the mother and thus the first breastfeeding session will be delayed. Women experiencing larger vaginal tears or retained placenta might also be subjected to the same clinical routine. In the univariate analyses, delayed breastfeeding (> 2 h) after birth was also associated with primiparity and the use of epidural anesthesia during labour. Given that primiparas tend to also breastfeed for a shorter period compared to multiparas [20], women with no previous breastfeeding experience might be in greater need for targeted breastfeeding support. Regarding the use of anesthetics during labour, it has been suggested to affect the newborns reflexes, making it more problematic for them to latch on, and therefore possibly complicating and postponing the first breastfeeding session [21]. Further, we noted an increased frequency of the hands-on approach when the first breastfeeding session takes place more than two hours postpartum, as has been previously described [22]. The higher rate of the hands-on approach among those women could indicate a wish to help and support mother-infant dyads to establish breastfeeding, but this model of breastfeeding support has been shown to increase negative experience of breastfeeding among women [22, 23]. Accordingly, women with a postponed breastfeeding initiation, were more likely to reported a negative first breastfeeding experience.

Despite the recommendations on exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months, only 77% of the participating women were breastfeeding exclusively at 6 weeks postpartum. Potential risk factors for an early discontinuation of breastfeeding or partial breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum were lower age, primiparity, low maternal education, obesity and depressive symptoms during pregnancy which have all been investigated and pointed out in previous research [12, 13, 20, 24, 25]. Likewise, caesarean section and other obstetric complications during labour, as well as a postponed first breastfeeding session were associated with not exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum. Women undergoing a caesarean section might experience more pain postpartum affecting breastfeeding negatively [26]. Also, women undergoing a planned caesarean section for psychosocial reasons, such as for example fear of childbirth, might be more vulnerable, possibly also having a lower breastfeeding self-efficacy [27]. Further, our results indicate that a negative first breastfeeding session and the use of the hands-on approach were associated with exclusive breastfeeding lasting less than six weeks, which is also likely linked to a low breastfeeding self-efficacy.

As shown in earlier research [12, 13, 15], women breastfeeding exclusively at six weeks had lower odds for significant depressive symptoms than women who did not. Breastfeeding seems to be associated with decreased odds of postpartum depression, whereas early breastfeeding cessation or negative early breastfeeding experience, as indicated by breastfeeding aversion or severe breastfeeding pain have been associated with a higher risk [28, 29]. This potentially protective effect of breastfeeding against depressive symptoms has been suggested to be exerted via attenuation of the cortisol response to stress, oxytocin release, improvement of the mother’s breastfeeding self-efficacy, emotional involvement and interaction with the infant [13]. Conversely, mothers with a history of depression or those experiencing postpartum depression also more often report shorter breastfeeding duration [29, 30].

Therefore, this study adds to the available evidence investigating the cumulative effect of antenatal depression and that postponed breastfeeding initiation, which also has a negative impact on breastfeeding duration [6,7,8]. In our study, parallelly, depression during pregnancy and late initiation of breastfeeding interacted in increasing the odds for non-exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum. Our results show that at six weeks postpartum, women with depressive symptoms during pregnancy and breastfeeding for the first time later than two hours postpartum had almost a 4-fold increase in the odds of not breastfeeding exclusively at six weeks postpartum. Women with depressive symptoms during pregnancy are a vulnerable group, and previous studies have concluded that these women tend to breastfeed for a shorter period [29, 30]. Depressive symptoms as well as the timing of the first breastfeeding session are also linked to a lower breastfeeding self-efficacy, pointing to that these women are in need of targeted encouraging breastfeeding support to enhance the chances of a longer exclusive breastfeeding duration [9, 31].

Conclusions

Our results show that women experiencing depressive symptoms during pregnancy, as well as those with a postponed first breastfeeding session, are more likely to not exclusively breastfeed at 6 weeks postpartum, which is the current recommendation. This could indicate a potential window of opportunity for intervention among the high-risk group of women with depressive symptoms in pregnancy within the first hours after birth, as they could possibly benefit from targeted breastfeeding support, thus enhancing the possibilities of longer exclusive breastfeeding duration. Lastly, if results from the current study could be confirmed in other settings, they should be disseminated among health care professionals in order to possibly revise routines during the first hours postpartum aiming to offer all women the possibility for early breastfeeding initiation of and subsequent adequate breastfeeding support, where needed.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CI:

-

Confidence Intervals

- DAG:

-

Directly Acycled Graph

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387(10017):491–504.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, Franca GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90.

World Health Organization. Implementation guidance: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services - the revised Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative. Geneva: World Health Orgnaization; 2018.]

Livsmedelsverket. Good food for babies [Spädbarn] Available from: www.livsmedelsverket.se/matvanor-halsa%2D%2Dmiljo/kostrad-och-matvanor/barn-och-ungdomar/spadbarn/ [Accessed 20th September 2017].

Socialstyrelsen. Statistic database for breastfeeding [Statistikdatabas för amning] Available from: www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/amning [Accessed 20th September 2017].

DiGirolamo AM, Grummer-Strawn LM, Fein SB. Effect of maternity-care practices on breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 2):S43–9.

Koskinen KS, Aho AL, Hannula L, Kaunonen M. Maternity hospital practices and breast feeding self-efficacy in Finnish primiparous and multiparous women during the immediate postpartum period. Midwifery. 2014;30(4):464–70.

Perez-Escamilla R, Martinez JL, Segura-Perez S. Impact of the baby-friendly hospital initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(3):402–17.

Haga SM, Ulleberg P, Slinning K, Kraft P, Steen TB, Staff A. A longitudinal study of postpartum depressive symptoms: multilevel growth curve analyses of emotion regulation strategies, breastfeeding self-efficacy, and social support. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(3):175–84.

Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N, Dowswell T. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(5):Cd003519.

Socialstyrelsen. Ten steps to successful breastfeeding [Tio steg som främjar amning] Available from: www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2014/2014-10-27 [Accessed 20th September 2017].

Figueiredo B, Canario C, Field T. Breastfeeding is negatively affected by prenatal depression and reduces postpartum depression. Psychol Med. 2014;44(5):927–36.

Figueiredo B, Dias CC, Brandao S, Canario C, Nunes-Costa R. Breastfeeding and postpartum depression: state of the art review. J Pediatr. 2013;89(4):332–8.

Werner E, Miller M, Osborne LM, Kuzava S, Monk C. Preventing postpartum depression: review and recommendations. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(1):41–60.

Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:142–54.

Iliadis SI, Koulouris P, Gingnell M, Sylven SM, Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Ekselius L, Papadopoulos FC, Skalkidou A. Personality and risk for postpartum depressive symptoms. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(3):539–46.

Rubertsson C, Borjesson K, Berglund A, Josefsson A, Sydsjo G. The Swedish validation of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) during pregnancy. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(6):414–8.

Wickberg B, Hwang CP. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale: validation on a Swedish community sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94(3):181–4.

Simkin P. Just another day in a woman's life? Part II: nature and consistency of women's long-term memories of their first birth experiences. Birth. 1992;19(2):64–81.

Hackman NM, Schaefer EW, Beiler JS, Rose CM, Paul IM. Breastfeeding outcome comparison by parity. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(3):156–62.

Brimdyr K, Cadwell K, Widstrom AM, Svensson K, Neumann M, Hart EA, Harrington S, Phillips R. The association between common labor drugs and suckling when skin-to-skin during the first hour after birth. Birth. 2015;42(4):319–28.

Cato K, Sylven SM, Skalkidou A, Rubertsson C. Experience of the first breastfeeding session in association with the use of the hands-on approach by healthcare professionals: a population-based Swedish study. Breastfeed Med. 2014;9(6):294–300.

Weimers L, Svensson K, Dumas L, Naver L, Wahlberg V. Hands-on approach during breastfeeding support in a neonatal intensive care unit: a qualitative study of Swedish mothers' experiences. Int Breastfeed J. 2006;1:20.

Kronborg H, Foverskov E, Vaeth M. Breastfeeding and introduction of complementary food in Danish infants. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(2):138–45.

Quinlivan J, Kua S, Gibson R, McPhee A, Makrides MM. Can we identify women who initiate and then prematurely cease breastfeeding? An Australian multicentre cohort study. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:16.

Karlstrom A, Engstrom-Olofsson R, Norbergh KG, Sjoling M, Hildingsson I. Postoperative pain after cesarean birth affects breastfeeding and infant care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(5):430–40.

Lowe NK. Self-efficacy for labor and childbirth fears in nulliparous pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21(4):219–24.

Watkins S, Meltzer-Brody S, Zolnoun D, Stuebe A. Early breastfeeding experiences and postpartum depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):214–21.

Ystrom E. Breastfeeding cessation and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:36.

Lindau JF, Mastroeni S, Gaddini A, Di Lallo D, Fiori Nastro P, Patane M, et al. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding cessation: identifying an "at risk population" for special support. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(4):533–40.

Henshaw EJ, Fried R, Siskind E, Newhouse L, Cooper M. Breastfeeding self-efficacy, mood, and breastfeeding outcomes among Primiparous women. J Hum Lact. 2015;31(3):511–8.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the participating women, as well as the staff at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology who helped with informing and recruiting patients.

Funding

AS received funding for designing the BASIC project, collection, analysis and interpretation of the material from the Swedish Research Council, the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation and the Uppsala University Hospital. CR received funding from the Uppsala University Hospital and KC received funding from the Gillbergska Foundation and the Uppsala University Hospital for designing the study, interpretation of the material and writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

According to the regulations of the Ethics Committee and the Swedish legislation, the clinical dataset generated and analyzed during the current study, cannot be made publicly available since that breeches local data protection laws. The data are however available from the corresponding author (KC) for inspection upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception of the study: AS, KC, SS, CR; data collection: AS, SS; data analysis and interpretation: KC, AS, MG, NK, SS, CR; drafting the article: KC, MG; critical revision of the article: AS, SS, NK, CR; final approval of the version to the published: KC, SS, MG, NK, CR, AS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written consent was obtained from all the participating women. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Research Committee of Uppsala, no 2009/171. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Graphical representation as directed acycled graph (DAG) of the conceptual model designed as to determine mediators and confounders in the association of interest between breastfeeding initiation at the first 2 h and exclusive breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum. (DOCX 334 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cato, K., Sylvén, S.M., Georgakis, M.K. et al. Antenatal depressive symptoms and early initiation of breastfeeding in association with exclusive breastfeeding six weeks postpartum: a longitudinal population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 49 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2195-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2195-9