Abstract

Background

Infection with vaginal microorganisms during labour can lead to maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity.

The objective of this systematic review is to review the effectiveness of intrapartum vaginal chlorhexidine in the reduction of maternal and neonatal colonisation and infectious morbidity.

Methods

Search strategy – Eight databases were searched for articles published in any language from inception to October 2016.

Selection criteria – Randomised controlled trials were included.

Data Collection and analysis - Publications were assessed for inclusion. Data were extracted and assessed for risk of bias.

Relative risks from individual studies were pooled using a random effects model and the heterogeneity of treatment was evaluated using Chi2 and I2 tests.

Results

Eleven randomised controlled trials (n = 20,101) evaluated intrapartum vaginal chlorhexidine interventions. Meta-analysis found no significant differences between the intervention and control groups for any of the four outcomes: maternal or neonatal colonization or infection. The preferred method for chlorhexidine administration was vaginal irrigation.

Conclusions

Meta-analysis did not demonstrate improved maternal or neonatal outcomes with intrapartum vaginal chlorhexidine cleansing, however this may be due to the limitations of the available studies. A larger, multicentre randomised controlled trial, powered to accurately evaluate the effect of intrapartum vaginal chlorhexidine cleansing on neonatal outcomes may still be informative; the technique of douching may be the most promising.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality continue to present a serious global problem. In 2015 over 137 million live births were estimated worldwide [1], and 2.7 million neonatal deaths. [1]., A further 303,000 maternal deaths were recorded in 2015 [2].

Between 30 and 40% of neonatal deaths worldwide are caused by infections [3, 4] and 10.7% of maternal deaths (37,285 annually worldwide) are due to sepsis [5]. The greatest burden exists in low-income countries, where 99% of neonatal and maternal deaths occur [6, 7]. Therefore, in order for interventions to have real potential for benefit, it is imperative that they are easily accessible, both financially and in practical application.

During the process of labour, both mother and fetus are susceptible to infection from a range of vaginal microorganisms including Group B streptococci (GBS), Campylobacter, Enterococcus faecalis, methicillin-resistant Streptococcus aureus, Klebsiellapneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Acinetobaumannii [8]. These organisms can lead to maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidities such as septicaemia, meningitis and pneumonia in the neonate [9] and chorioamnionitis leading to severe pelvic infection in the mother [10].

The maternal and fetal microbial profile may differ between geographical regions, with GBS having prominence in high-income countries [11]. However, it has been hypothesised that this prominence may be due to the underestimation of GBS prevalence in low income countries; facilities for detection are rarely available and many births take place outside a formal healthcare setting [12]. Thus far, many studies have focused separately on GBS and other vaginal microbes [9, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

GBS in the neonate is usually acquired through vertical transmission from the mother’s genital tract [23]. A number of strategies have been suggested to reduce vertical transmission of pathogens which colonise the maternal genital tract [13], including the use of intrapartum chemoprophylaxis for GBS-colonised mothers [24] and whole-body washing with chlorhexidine during the last 2 weeks of pregnancy [14]. In particular an important research question has been the use of a chlorhexidine antiseptic to cleanse the vagina during labour to reduce both maternal and neonatal infection [15, 20, 25,26,27,28,29,30].

Chlorhexidine is a bisguanide antiseptic, which works by disrupting the bacterial cell wall [31]. It is effective against most gram-positive and some gram-negative bacteria, yeasts and many viruses, although variably effective against enveloped viruses [31]. It is ineffective against bacterial spores and mycobacteria [31]. Christensen et al. [13] found that GBS was extremely sensitive to chlorhexidine, with a minimum inhibitory concentration of 0.5-1 mg/l [32].Chlorhexidine has been shown to have activity against normal vaginal bacteria, which cause puerperal infection, including GBS, E.coli and enterococci [33]. Upon application it is immediately effective, suppressing bacterial growth for up to 24 h [15]. Although not deactivated by alcohol, soaps or lavage fluid, the presence of organic matter such as blood or amniotic fluid may reduce the effectiveness of chlorhexidine [31].

The broad-spectrum antisepsis of the compound makes it particularly suitable for use in the intrapartum environment, where the colonisation of neonates and infectious morbidity of mothers shows an ever-changing pattern [34]. It is effective at a lower pH, which further supports its use in the vagina, which typically has an environment of pH < 4.7 [35].Chlorhexidine is inexpensive, has no effect on antimicrobial resistance, and is practical and viable to be used in resource-limited settings [36]. It also has a good safety profile [37] and has been studied in the obstetric setting in concentrations ranging from 0.05–4% [11] The compound is widely available from numerous manufacturers worldwide. Chlorhexidine has thus been proposed as a highly suitable compound for intra-vaginal use to reduce maternal and neonatal sepsis [12, 38].

In 1989, the observation of a reduction of neonatal GBS colonisation led to the recommendation for a larger multicentre trial [16]. More recently, two Cochrane reviews of randomised controlled trials examined aspects of this question [17, 18] both of which were updated in 2014 [9, 19]. Lumbiganon et al. [9] reported data in their Cochrane review which focused on trials comparing chlorhexidine vaginal douching during labour with placebo or other vaginal disinfectant to prevent maternal and neonatal infections, excluding GBS and HIV. The results suggested a trend in the reduction of endometritis through intrapartum vaginal chlorhexidine, but this was not statistically significant. Ohlsson et al. [19] found that a vaginal intrapartum chlorhexidine intervention reduced the GBS colonisation of neonates, but did not reduce early-onset disease, including GBS infection, GBS pneumonia or GBS meningitis. The authors of both reviews concluded that a randomised controlled trial with adequate power and standardised intervention was required, but Ohlsson et al. [19] commented that in developed countries, this may be difficult to justify in the era of antibiotic prophylaxis for GBS infection. However, the scope of these reviews was narrower than this review, and excluded a number studies as they combined the interventions of vaginal cleansing and infant washing. Furthermore the Cochrane reviews separated neonatal infections based on the microorganism responsible, making an overall assessment of the efficacy of this intervention difficult.

The following systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials focuses on the intrapartum vaginal interventions in vaginal deliveries only, measuring both maternal and neonatal outcomes in terms of infectious morbidity and mortality, irrespective of infectious organisms.

Methods

Types of studies included randomised controlled trials only, comparing the use of intrapartum vaginal chlorhexidine cleansing to no chlorhexidine use or placebo or other vaginal disinfectant, for the reduction of maternal or neonatal infection. Studies that considered HIV-positive participants exclusively were excluded.

Participants considered for inclusion in this review are women undergoing vaginal delivery, in the intrapartum period and having vaginal chlorhexidine cleansing in any setting.

Types of interventions considered were vaginal disinfection with chlorhexidine by any method during labour, compared with placebo or no vaginal disinfection.

Maternal outcomes measured were 1) Colonization during the post-partum period and 2) Clinical infection and / or sepsis during the post-partum period. Neonatal outcomes measured were 1) Colonization during the neonatal period and 2) Clinical infection and / or sepsis during the neonatal period.

Eight electronic databases were searched (PubMed, Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, AIM, the Reproductive Health Library, and BioMed Central: from database inception to 10/2016. The following search terms were used ‘Chlorhexidine’, ‘vaginal antiseptic’, ‘vaginal wipe’, ‘vaginal douche’, ‘vaginal cleansing’, ‘bathing’ with ‘pregnancy’, ‘postpartum’, ‘labour’ ‘intrapartum’, ‘neonatal’, ‘peripartum’ and ‘meningitis’, ‘pneumonia’ ‘group B strep’, ‘infection’, ‘HIV’, ‘sepsis’, ‘mortality’, ‘omphalitis’, ‘Klebsiella’, ‘chorioamnionitis’, ‘endometritis’, ‘maternal’, ‘infant’, ‘postnatal’. No language restrictions were applied. Databases were searched for papers published until October 2016.

All randomised trials examining the use of vaginal chlorhexidine washing during labour, by any method, which reported maternal or neonatal outcomes were included.

Three authors completed the searches independently (C Bell, L Hughes, T Akister). Two authors independently (C Bell, L Hughes) screened the titles and abstracts to assess for inclusion or exclusion. The two authors then read each paper identified as a result of the search strategy and made a decision on whether it should be included or excluded on the basis of all the defined inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion (T Akister, D Lissauer).

Data was extracted by two authors independently (T Akister, V Ramkhelawon) and tabulated using Miscrosoft Excel. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion amongst the authorship group and consensus. Data was entered into Review Manager Software Revman 5.0 and checked for accuracy.

Two review authors (T Akister, V Ramkhelawon) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [39]. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third review author.

Specifically, the following aspects of risk bias were assessed in detail: 1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias), 2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias), 3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias), 4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations), 5) Selective reporting bias, 6) Other sources of bias.

The overall risk of bias was made using judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [39]. The likely magnitude and direction of the biases described in points 1 to 6 above was assessed and whether it was likely to impact on the findings.

Data for effect estimates, including 95% confidence intervals, were directly extracted. These results were then included in the meta-analysis, using a random effects model to pool the relative risks from individual studies. The heterogeneity of treatment was evaluated using Chi2 and I2 tests and presented as forest plots. Analyses were undertaken using Revman 5.0 statistical software and Mantel-Haenszel analysis.

Results

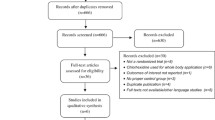

We identified 68 unique papers after searching PubMed, Embase, Medline, The Cochrane Library and Biomed Central. No papers were identified after searching the CINAHL, AIM or RHL databases. Eleven RCTs involving 20,101 women and their infants, were suitable to be included in a systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Characteristics of included studies are detailed in Table 1, including potential confounding factors. Only two of the studies [27, 40] were undertaken in low resource settings (Table 1).

There was no significant difference in maternal colonization when using vaginal chlorhexidine intrapartum when compared to the control (Fig. 2). Two studies [21, 27] investigated the effect of chlorhexidine on maternal colonization, including 53 participants in the intervention group and 51 in the control group, which also showed no significant difference on colonization (Relative risk (RR) 0.61, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.05-8.08) Heterogeneity – I2 = 93%, P < 0.001.

Forest plot comparing the following outcomes and interventions: 1) maternal colonisation; 2) maternal sepsis/infection; 3) neonatal colonisation; 4) neonatal sepsis/infection; 5) maternal sepsis/infection – douching; 6) maternal sepsis/infection – wipes; 7) neonatal colonisation – douching; 8) neonatal colonisation – gel/cream

Five studies [28, 30, 40,41,42] (Fig. 2) containing a total of 12,154 participants (6067 intervention and 6087 control) did not show a statistically significant effect in maternal morbidity (RR 0.91 95% CI 0.69-1.20) with the chlorhexidine intervention. Heterogeneity – I2 = 52%, P = 0.08.

The incidence of neonatal colonization was not reduced with any chlorhexidine intervention (Fig. 2). Three studies [22, 42, 43] reported on neonatal colonization on a total of 1948 neonates (949 intervention 999 control) and also showed no reduction in bacterial transmission (RR 0.75 CI 0.46-1.22). Heterogeneity – I2 = 90%, P < 0.001.

Five studies [20, 29, 30, 41, 42] (Fig. 2) looked at neonatal infection and sepsis. This included 4297 infants in the intervention arm and 4342 in the control group. There was also no reduction with vaginal chlorhexidine (RR 0.74 CI 0.52-1.06). There was significant heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of neonatal colonization (p < 0.001, I2 = 90%), but no evidence of significant heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of neonatal sepsis/infection as their outcome (p < 0.26, I2 = 24%). Further analysis of this outcome was undertaken, discriminating between douching and wipes/gel/cream (Fig. 2). The results favoured the douching method, for which the result for neonatal colonization was significant (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, this particular analysis only contained one study [42].

Discussion

The meta-analysis did not demonstrate a reduction in maternal colonization or in maternal sepsis/infection when using intrapartum vaginal chlorhexidine cleansing. The incidences of neonatal colonization and neonatal infection/sepsis were also not significantly reduced by this intervention. However, although these results did not show a statistically significant reduction in outcomes, there appeared to be a trend towards a reduction in maternal infection and neonatal colonisation and infection with the douching method, which suggest this subject may warrant further study.

All of the 11 studies reviewed were randomised trials, but seven were assessed to be at high risk of bias in one or more categories. For example, two studies [23, 27] did not perform an intention to treat analysis, which can lead to a failure to preserve randomisation of the groups.

There is significant clinical heterogeneity in the studies analysed (Table 1). In particular, different methods of vaginal cleansing with chlorhexidine were used. In eight studies [20, 21, 27, 30, 41, 42, 44] an irrigation or ‘douching’ method was used, whilst others used gel [23], wipes [40] or cream [22] . In the analysis of these treatment differences, douching was suggested to be more effective, but this may not be a reliable conclusion as only one study [42] with neonatal colonization as an outcome employed irrigation and only one study with maternal sepsis/infection as an outcome [40] used wipes. It is however conceivable that the act of mechanically flushing the vaginal walls could play a part in the physical removal of pathogenic and commensal bacteria. This would oppose the theory that a prolonged contact time found with the use of gel or cream would enhance the bactericidal effects of chlorhexidine.

The use of a control also varied between studies, with three [20, 41, 42] using sterile saline, three [28, 30, 44] using sterile water, one [23] using another placebo and four [21, 22, 27, 40] using no intervention as controls. Aside from the lack of blinding in the non-treatment controls, confounding may have occurred in the use of saline or water. The effect of these controls on vaginal bacteria, whether chemical or mechanical, should be determined.

Some studies included in their analysis the outcomes of mothers who underwent emergency caesarean section [20, 23, 30, 41]. Studies that exclusively focused on women undergoing caesarean section were excluded from our review, but a proportion of women in labour will inevitably require surgical intervention. The intention-to-treat analysis employed may have preserved randomisation, but may also have had an impact on the outcome, as the contamination of the neonate with vaginal bacteria may be less likely if that neonate has not passed through the vagina. Notably, the studies by Rouse et al. [30, 41] also administered one dose of a second-generation cephalosporin to these mothers, which also risks masking the effects of vaginal washing on maternal infection. The same studies also gave prophylactic antibiotics to any mother at risk of early onset GBS infections, which may also have masked both maternal and neonatal complications. In contrast, Burman et al. [20] had ‘GBS carrier status’ as an inclusion criterion (Table 1). In addition, some of the studies did not take account of the duration of labour or prolonged rupture of membranes, which may have led to bias, whilst the Rouse studies [30, 41] administered prophylactic antibiotics to these participants (Table 1).

The studies reviewed also differ in terms of the level of care provider carrying out the intervention, with four [20, 21, 40, 42] using midwives and five [23, 28, 30, 41, 44] using doctors and/or medical students, two unknown [22, 27]. However, the person(s) within each study responsible for performing the intervention (or control, where applicable) varied within the study itself, which may also have influenced outcomes.

The studies reviewed showed heterogeneity for their location. Nine studies were conducted in high-income countries (4 USA, 5 Scandinavia) and only two in developing countries (1 South Africa, 1 Zimbabwe). The Zimbabwean study [27] showed a highly statistically significant result favouring the use of chlorhexidine for the prevention of maternal colonisation. The South African study failed to show a favourable result for the outcome of maternal infection/sepsis. Notably, this study also used vaginal wiping instead of irrigation as the method of intervention, which may be a less effective technique. However, despite such notable heterogeneity between studies, the authors feel that the studies showed sufficient homogeneity in their populations, interventions and outcomes to warrant meta-analysis. It was also felt that the efficacy of the intervention, that is vaginal, intrapartum chlorhexidine, should not be directly affected by the geographical location of the study. Nonetheless, the intervention itself may be economically and technically viable for a low-income setting.

Cochrane reviews [9, 17,18,19] have previously focused on GBS and other infections separately, concluding that intravaginal/intrapartum chlorhexidine was effective in significantly reducing neonatal colonization with GBS. But they stated that this alone was not sufficient to support the use of the intervention. Our review has also found that, when assessing maternal and neonatal colonization and infectious morbidity of all organisms (excluding HIV) there is no statistical significance to the results, but there is a suggestion that intervention may lead to a reduction in neonatal infection/sepsis.

Goldenberg et al. [38] analysed studies using vaginal chlorhexidine, with or without a neonatal wash, with particular reference to the low income countries. Their analysis of two large, non-randomised studies suggested that one or both of these interventions was successful in improving both maternal and neonatal outcomes. However we believe that it is still useful to separate the two interventions as in our review, to determine the individual effect of each. This is particularly important when considering potential implementation in the low-income countries, where cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses would be of paramount importance, as well as the simplicity of the intervention.

McClure et al. [11] reviewed studies using any chlorhexidine interventions including vaginal, neonatal wipes and umbilical cord cleansing. The group suggested that although several studies reviewed showed promising results, the lack of truly randomized trial evidence stood as a major barrier to implementing the use of chlorhexidine interventions in low-resource settings. Again, we feel that it is advantageous to separate the interventions in order to assess their individual efficacy as exclusive interventions, before combining the outcomes in such a review. Mullany et al. [12] used similar inclusion criteria to McClure et al. [11] for their review, which concluded that although the various chlorhexidine interventions showed promise in reducing neonatal morbidity and mortality, their individual efficacy should be determined before implementation in low-resource settings. We have begun this process in our review, in order to ascertain whether a larger scale randomised controlled trial would be justifiable for the separate intervention of vaginal chlorhexidine washing.

The two Cochrane reviews did this in relation to vaginal, intrapartum chlorhexidine, but may have limited interpretation by separating the causative organisms. As it has been hypothesized that the apparent low prevalence of GBS in low-resource settings may be attributable to under-diagnosis [12], we felt that it was important to conduct our review to include all causative agents.

The Dykes [21], Adriaanse [23], Burman [20] and Stray-Pedersen [42] studies all supported the use of vaginal intrapartum chlorhexidine. All of these studies were conducted in Scandinavian hospitals; therefore the results may not be generalisable to the populations of less developed countries, where a majority of the maternal and neonatal burden of disease exists. Furthermore it is in this setting that the lack of resources and high number of community births make an effective, safe, cheap and low-skill intervention particularly beneficial. In this setting non-randomised studies such as Mushangwe [45] and Taha [46] show promising results.

Conclusions

Our review shows that intrapartum, vaginal chlorhexidine may lead to a reduction in neonatal infection/sepsis. It is still unclear whether chlorhexidine concentration and method of administration will have a significant impact on outcome, due to the heterogeneity of existing studies. It is therefore our belief that a larger, multicentre, randomised controlled clinical trial in a low-resource setting is justified based on our analysis. Such a trial would require rigorously defined inclusion criteria such as in the Rouse et al. studies [30, 41]. These patients were nulliparous, more than 32 weeks gestation and exclusion criteria were: contraindication to digital cervical examination, active genital herpes, chorioamnionitis prior to randomisation and allergy to chlorhexidine. The studies also carried out double-blinding and computer randomisation.

The use of intrapartum vaginal chlorhexidine should also be considered separately to neonatal skin cleansing, to provide more specific information regarding the efficacy of such interventions. As there are still unanswered question regarding the optimum concentration of chlorhexidine, the frequency and timing (pre/post rupture of membranes) of the intervention and the method used (wipes/gel/cream versus douching), further studies may need to also address these issues.

Abbreviations

- GBS:

-

Group B streptococci

References

World Health Organisation. World health statistics 2015. Luxembourg: WHO Press; 2015.

Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller A-B, Gemmill A, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN maternal mortality estimation inter-agency group. Lancet. 387(10017):462–74.

Sankar MJ, Chandrasekaran A, Ravindranath A, Agarwal R, Paul VK. Umbilical cord cleansing with chlorhexidine in neonates: a systematic review. J Perinatol. 2016;36(S1):S12–20.

Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since. Lancet. 2000;379(9832):2151–61.

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller A-B, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):e323-e33.

Gogia S, Sachdev HPS. Home-based neonatal care by community health workers for preventing mortality in neonates in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Perinatol. 2016;36(S1):S55–73.

Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? The Lancet. 2005;365(9462):891-900.

Lim WH, Lien R, Huang Y-C, Chiang M-C, Fu R-H, Chu S-M, et al. Prevalence and pathogen distribution of neonatal sepsis among very-low-birth-weight infants. Pediat Neonatol. 2012;53(4):228-34.

Lumbiganon P, Thinkhamrop J, Thinkhamrop B, Tolosa JE. Vaginal chlorhexidine during labour for preventing maternal and neonatal infections (excluding Group B Streptococcal and HIV). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD004070. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004070.pub3.

Moyo SR, Hägerstrand I, Nyström L, Tswana SA, Blomberg J, Bergström S, et al. Stillbirths and intrauterine infection, histologic chorioamnionitis and microbiological findings. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1996;54(2):115-23.

McClure EM, Goldenberg RL, Brandes N, Darmstadt GL, Wright LL. The use of chlorhexidine to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity in low-resource settings. Int J of Gynecol Obstet. 2007;97(2):89-94.

Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Tielsch JM. Safety and impact of chlorhexidine antisepsis interventions for improving neonatal health in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(8):665–75.

Christensen K, Christensen P, Dykes A, Kahlmeter G. Chlorhexidine for prevention of neonatal colonization with group B streptococci. III. Effect of vaginal washing with chlorhexidine before rupture of the membranes. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol. 1985;19(4):231–6.

Sanderson PJ, Haji TC. Transfer of group B streptococci from mothers to neonates: effect of whole body washing of mothers with chlorhexidine. J Hospital Infect. 1985;6(3):257-64.

Dykes A-K, Christensen KK, Christensen P, Kahlmeter G. Chlorhexidine for prevention of neonatal colonization with group B streptococci. II. Chlorhexidine concentrations and recovery of group B streptococci following vaginal washing in pregnant women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;16(3):167-72.

Kollée LAA, Speyer I, van Kuijck MAP, Koopman R, Dony JM, Bakker JH, et al. Prevention of group B streptococci transmission during delivery by vaginal application of chlorhexidine gel. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;31(1):47-51.

Lumbiganon P, Thinkhamrop J, Thinkhamrop B, Tolosa JE. Vaginal chlorhexidine during labour for preventing maternal and neonatal infections (excluding Group B Streptococcal and HIV). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004(4).

Stade BC, Shah VS, Ohlsson A. Vaginal chlorhexidine during labour to prevent early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004(3).

Ohlsson A, Shah VS, Stade BC. Vaginal chlorhexidine during labour to prevent early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(12).

Burman LG, Fryklund B, Helgesson AM, Christensen P, Christensen K, Svenningsen NW, et al. Prevention of excess neonatal morbidity associated with group B streptococci by vaginal chlorhexidine disinfection during labour. Lancet. 1992;340(8811):65–9.

Dykes A-K, Christensen KK, Christensen P. Chlorhexidine for prevention of neonatal colonization with group B streptococci. IV. Depressed puerperal carriage following vaginal washing with chlorhexidine during labour. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1987;24(4):293–7.

Henneguin Y, Tecco L, Vokaer A. Use of chlorhexidine during labor: how effective against neonatal group B streptococci colonization? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74(2):168.

Adriaanse AH. 8b prevention of neonatal septicaemia due to group B streptococci. Baillières Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;9(3):545–52.

Schuchat A. Impact of intrapartum chemoprophylaxis on neonatal sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(12):1087–8.

Rouse DJ, Hauth JC, Andrews WW, Mills BB, Maher JE. Chlorhexidine vaginal irrigation for the prevention of peripartal infection: a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(3):617-22.

Stray-Pedersen B, Bergan T, Hafstad A, Normann E, Grøgaard J, Vangdal M. Vaginal disinfection with chlorhexidine during childbirth. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;12(3):245-51.

Pereira L, Chipato T, Mashu A, Mushangwe V, Rusakaniko S, Bangdiwala SI, et al. Randomized study of vaginal and neonatal cleansing with 1% chlorhexidine. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112(3):234–8.

Sweeten KM, Eriksen NL, Blanco JD. Chlorhexidine versus sterile water vaginal wash during labor to prevent peripartum infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(2):426–30.

Facchinetti F, Piccinini F, Mordini B, Volpe A. Chlorhexidine vaginal flushings versus systemic ampicillin in the prevention of vertical transmission of neonatal group B streptococcus, at term. (RG) Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009:84-88.

Rouse DJ, Hauth JC, Andrews WW, Mills BB, Maher JE. Chlorhexidine vaginal irrigation for the prevention of peripartal infection: a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(3):617–22.

Burkitt Creedon J, Davis H. Advanced monitoring and procedures for small animal emergency and critical care. Chichester: Wiley; 2012.

Al-Tannir MA, Goodman HS. A review of chlorhexidine and its use in special populations. Spec Care Dent. 1994;14(3):116–22.

Vorherr H, Vorherr UF, Mehta P, Ulrich JA, Messer RH. Antimicrobial effect of chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine on vaginal bacteria. J Infect. 1984;8(3):195–9.

Bizzarro MJ, Raskind C, Baltimore RS, Gallagher PG. Seventy-five years of neonatal Sepsis at Yale: 1928–2003. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):595–602.

Ferris DG, Francis SL, Dickman ED, Miler-Miles K, Waller JL, McClendon N. Variability of vaginal pH determination by patients and clinicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(4):368–73.

Schuchat A. Group B streptococcus. Lancet. 1999;353(9146):51–6.

Saleem S, Reza T, McClure EM, Pasha O, Moss N, Rouse DJ, et al. Chlorhexidine vaginal and neonatal wipes in home births in Pakistan: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):977–85.

Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Saleem S, Rouse D, Vermund S. Use of vaginally administered chlorhexidine during labor to improve pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):1139–46.

JPT Higgins, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Cutland CL, Madhi SA, Zell ER, Kuwanda L, Laque M, Groome M, et al. Chlorhexidine maternal-vaginal and neonate body wipes in sepsis and vertical transmission of pathogenic bacteria in South Africa: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9705):1909–16.

Rouse DJ, Cliver S, Lincoln TL, Andrews WW, Hauth JC. Clinical trial of chlorhexidine vaginal irrigation to prevent peripartal infection in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):166–70.

Stray-Pedersen B, Bergan T, Hafstad A, Normann E, Grøgaard J, Vangdal M. Vaginal disinfection with chlorhexidine during childbirth. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;12(3):245–51.

Adriaanse AH, Kollée LAA, Muytjens HL, Nijhuis JG, de Haan AFJ, Eskes TKAB. Randomized study of vaginal chlorhexidine disinfection during labor to prevent vertical transmission of group B streptococci. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;61(2):135-41.

Eriksen NL, Sweeten KM, Blanco JD. Chlorhexidine vs. sterile vaginal wash during labor to prevent neonatal infection. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1997;5(4):286–90.

Mushangwe V, Tolosa JE, Pereira L, Mashu A, Bangdiwala S, Rusakaniko S, et al. Chlorhexidine washing of the vagina in labor effectively reduces bacterial colonization: A study by the global network for perinatal & reproductive health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(6):S66.

Taha TE, Biggar RJ, Broadhead RL, Mtimavalye LAR, Miotti PG, Justesen AB, et al. Effect of cleansing the birth canal with antiseptic solution on maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality in Malawi: clinical trial. BMJ. 1997;315(7102):216.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Searches were completed by CB, LH and TA. Screening and assessment for inclusion/exclusion - CB, LH. Disagreement resolution - TA, DL. Data extraction and risk of bias analysis - TA, VR. Disagreement resolution - CB, LH. Methodological support, AW, DL. All authors drafted, edited and approved the final manuscript. DL and AW were funded as part of the Antibiotics in miscarriage surgery trial, by the Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, UK Aid, Joint global health trials programme; Trial registration ISRCTN97143849.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bell, C., Hughes, L., Akister, T. et al. What is the result of vaginal cleansing with chlorhexidine during labour on maternal and neonatal infections? A systematic review of randomised trials with meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 139 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1754-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1754-9