Abstract

Background

Although the onset of gestational diabetes (GDM) is known to be a significant risk factor for the future development of type 2 diabetes, this risk specifically in women with GDM diagnosed by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG) criteria has not yet been thoroughly investigated. This study was performed to investigate the risk factors associated with the development of postpartum diabetes in Japanese women with a history of GDM, and the effects of the differences in the previous Japanese criteria and the IADPSG criteria.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included Japanese women with GDM who underwent at least one postpartum oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 2003 and 2014. Cases with overt diabetes in pregnancy were excluded. We investigated the risk factors including maternal baseline and pregnancy characteristics associated with the development of postpartum diabetes.

Results

Among 354 women diagnosed with GDM during the study period, 306 (86%) (116/136 [85.3%] and 190/218 [87.2%] under the previous criteria and the IADPSG criteria, respectively) who underwent at least 1 follow-up OGTT were included in the study. Thirty-two women (10.1%) developed diabetes within a median follow-up period of 57 weeks (range, 6–292 weeks). Eleven (9.5%) and 21 (11.1%) were diagnosed as GDM during pregnancy based on the previous Japanese criteria and the IADPSG criteria, respectively, which did not significantly differ between those criteria. A multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that HbA1c and 2-h plasma glucose (PG) at the time of the diagnostic OGTT during pregnancy were independent predictors of the development of diabetes after adjusting for confounders. The adjusted relative risk of HbA1c ≥5.6% for the development of diabetes was 4.67 (95% confidence interval, 1.53-16.73), while that of 2-h PG ≥183 mg/dl was 7.02 (2.51-20.72).

Conclusions

A modest elevation of the HbA1c and 2-h PG values at the time of the diagnosis of GDM during pregnancy are independent predictors of the development of diabetes during the postpartum period in Japanese women with a history of GDM. The diagnostic criteria did not affect the incidence of postpartum diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The onset of gestational diabetes (GDM) during pregnancy is known to be a significant risk factor for the future development of type 2 diabetes. The odds ratio, in comparison to patients who are normoglycemic during pregnancy, is 7.43 [1]. Although evidence to support this was already published in 1978 [2], it has received much more attention in the background of the recent worldwide pandemic of diabetes and obesity [3]. In this background, women with a history of GDM have been becoming a key target population in efforts to prevent the future development of diabetes.

In 2010, new international diagnostic criteria for GDM were published [4]. The criteria were based on evidence of the perinatal outcomes. Thus, it has not been well investigated whether women with GDM who are diagnosed according to the IADPSG criteria are at a similarly high risk of developing postpartum diabetes. We previously reported that there was no significant difference in the effect of the early postpartum development of impaired glucose tolerance between the IADPSG criteria and the previous Japanese criteria [5]. However, it is still not clear whether the differences in the diagnostic criteria affect the risk of the future development of diabetes.

The introduction of the IADPSG criteria has resulted in a 3-fold increase in the prevalence of GDM in the Japanese population [6]. Thus, a more efficient follow-up system is necessary for screening for postpartum diabetes. The triage of high-risk women to more intensive follow-up protocols seems to be more relevant. There seem to be a large number of risk factors, including maternal characteristics and pregnancy factors that are linked to the future development of type 2 diabetes in women with a history of GDM [7]. The maternal characteristics include maternal obesity, a family history of diabetes, ethnicity, advanced maternal age. The pregnancy factors include, but are not limited to, an early diagnosis of GDM, fasting hyperglycemia, an elevated HbA1c value, and insulin use [7]. In our previous study, we aimed to demonstrate the risk factors associated with abnormal glucose tolerance at 6–8 weeks postpartum [5]. However, thus far, no studies of Japanese subjects that followed up patients beyond the early postpartum period have been reported.

In this current study, we aimed to identify the risk factors associated with the development of diabetes in Japanese women with a history of GDM over a longer postpartum period, and to investigate whether the differences between the previous Japanese criteria and the IADPSG criteria influence the risk of the development of postpartum diabetes.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study of a single perinatal care center in Japan, we obtained data for women with GDM who underwent postpartum 75-g oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) at the National Hospital Organization Nagasaki Medical Center (Omura, Japan) between January, 2003 and December, 2014. We used two different diagnostic criteria during this period: the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) criteria [8], which were used until June 2010; and the IADPSG criteria, which were used from July 2010 (Table 1). Because of the possibility of pregestational diabetes, we excluded women who were diagnosed with overt diabetes during pregnancy according to the IADPSG criteria [4], including those with a fasting plasma glucose level of ≥126 mg/dl or an HbA1c level of ≥6.5% on an OGTT during pregnancy. We only included women of Japanese ethnicity in the present study. In both of the study periods with different diagnostic criteria, to screen for GDM during pregnancy, we performed universal screening of all pregnant women using a 50-g glucose challenge test around 24 weeks’ gestation; those with values of ≥135 mg/dL underwent a diagnostic 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) after overnight fasting. We also measured the HbA1c values at the time of the diagnostic OGTT.

We used the standard treatment practices for women with GDM, including diet and insulin therapy based on the results of the self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG) level. Insulin therapy was prescribed if the patient achieved less than 80% of the target blood glucose levels, including fasting and 2-h postprandial blood glucose levels of <95 mg/dl and <120 mg/dl, respectively. We did not prescribe any oral hypoglycemic agents during pregnancy or the postpartum period.

Women with a history of GDM underwent the first follow-up OGTT at 6–8 weeks postpartum; thereafter, the test was then repeated every 6–12 months. We defined postpartum diabetes according to the WHO criteria [9] (Table 1).

We obtained the patients’ basic maternal characteristics including their age, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), and family history of diabetes (defined as unspecified diabetes among first- and second-degree relatives). We also obtained data related to their pregnancy, including the gestational age (GA) at the time of the diagnostic OGTT, the plasma glucose (PG) and HbA1c levels at the time of the diagnostic OGTT, the requirement of insulin therapy, and weight gain throughout pregnancy.

The primary outcome measure was postpartum development of diabetes. We investigated the association between the primary outcome measure and the risk factors, including the basic maternal and perinatal characteristics. We first used a univariate logistic regression analysis to test the association between each risk factor and the postpartum development of diabetes. Factors with a p value of <0.05 on the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis. The multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to test for independent associations between risk factors and the development of diabetes. In the multivariate analysis, we converted the factors that were numerically associated with the development of postpartum diabetes into categorical variables as a clinical viewpoint. A receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve was used to identify the optimum cut-off values for those variables. We also used Student’s t-test and a chi-squared test to compare numerical variables and the difference in ratios between groups, respectively. P values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. This study was conducted with the approval of the Institution Review Board of Nagasaki Medical Center to collect the clinical data with informed consent.

Results

We included 306 women who underwent at least one postpartum follow-up OGTT. In the same period, 354 women were diagnosed with GDM, including 136 and 218 by the JSOG and the IADPSG criteria, respectively. Among the patients who underwent at least 1 postpartum OGTT, 116 (38%) and 190 (62%) women were diagnosed according to the JSOG and IADPSG criteria, respectively. Thus, the follow-up rate (defined by the performance of at least 1 postpartum OGTT) was 86% (306/354) in total subjects and 85.3% (116/136) and 87.2% (190/218) in the JSOG and the IADPSG criteria, respectively. The maternal characteristics of the patients in each group and the results of their diagnostic OGTTs during pregnancy are shown in Table 2. The PG levels during the diagnostic OGTT were significantly higher in women during the JSOG period (JSOG group) than they were during the IADPSG period (IADPSG group). The rates of women who underwent two or more follow-up OGTTs in the JSOG and IADPSG periods were 70% and 78%, respectively, and did not differ to a statistically significant extent. More than half of the women underwent an OGTT at more than one year postpartum. There was a significant difference in the length of the follow-up period between the two groups (Table 2).

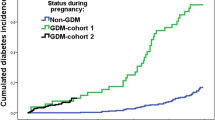

During the mean follow-up period of 68 ± 61 weeks (median, 57 weeks; range, 7–292 weeks), 32 (10.5%) women developed diabetes within a follow-up period of 59 ± 53 weeks (median, 47 weeks; range, 7–230 weeks). This rate was not significantly different from that of the women who did not develop diabetes (mean, 69 ± 62 weeks; median, 58 weeks; range 7–292 weeks). Eleven (9.5%) and 21 (11.1%) women with diabetes were included in the JSOG and IADPSG groups, respectively (Table 2); the incidence was not different between the different diagnostic criteria group even after adjusting for the follow-up period. Regarding the time period from the index delivery to the onset of diabetes in those who developed diabetes, women diagnosed under the IADPSG criteria developed diabetes significantly sooner than those diagnosed under the JSOG criteria (44 ± 26 vs. 88 ± 78 weeks, p = 0.024).

The women who developed postpartum diabetes were more obese before pregnancy (p = 0.0032), showed elevated 2-h PG (p = 0.016) and HbA1c (p < 0.0001) levels at the time of the diagnostic OGTT, and required more insulin therapy during pregnancy (p = 0.0031) in comparison to those who did not develop diabetes during the study period (Table 3). A univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that a higher pre-pregnancy BMI (p = 0.0044), 2-h PG (p = 0.016), HbA1c (p < 0.0001), and the requirement of insulin therapy (p = 0.0031) were significant risk factors for the postpartum development of diabetes (Table 4). In multivariate regression models that used the variables that were identified as significant in the univariate analysis, we found that only the 2-h PG and HbA1c levels were independent predictors of the development of diabetes during the postpartum period (Table 5). The association remained significant after controlling for maternal age, parity, a family history of diabetes, the GA and fasting and 1-h PG at the OGTT, weight gain during pregnancy, and the follow-up period (Table 5). Because fasting and the 1-h PG showed near-significance in the univariate analysis (Table 4), we also examined the association between those two variables and the development of diabetes by a multivariate analysis including these two variables in addition to the four significant variables and found that neither fasting nor the 1-h PG was significantly associated with the postpartum disorder.

From the clinical point of view, we converted these numerical variables to categorical variables (Table 6). We used cutoff values of 183 mg/dl (area under the curve [AUC] 0.64) and 5.6% (AUC 0.74) for 2-h PG and HbA1c, respectively, which were derived from the ROC. A 2-h PG value of ≥183 mg/dl and an HbA1c value of ≥5.6% were significantly associated with the development of postpartum diabetes with an adjusted relative risk (RR) of 7.02 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.51–20.72, p = 0.0002) and 4.67 (95% CI 1.53–16.73, p = 0.0061), respectively (Table 6).

Discussion

In this retrospective Japanese cohort study, 10.5% of women with a history of GDM developed diabetes during a median follow-up period of 57 weeks within up to 5 years. We also found that the 2-h PG and HbA1c values during the diagnostic 75-g OGTT in pregnancy were significant independent predictors of the postpartum development of diabetes, with an RR of 7.02 and 4.67, respectively, if a 2-h PG level of ≥183 mg/dl and an HbA1c value of ≥5.6% were used as cutoff values, after adjusting for the considerable confounders. With regard to the diagnostic criteria, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of the development of postpartum diabetes between the women who were diagnosed by the JSOG criteria (9.5%) and those who were diagnosed by the IADPSG criteria (11.1%).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report regarding the development of diabetes at more than one year postpartum in Japanese women with a history of GDM. In addition, among many follow-up studies of GDM patients, few studies have reported the prevalence of postpartum diabetes in women with a history of GDM who were diagnosed according to the IADPSG criteria. We found that the prevalence of postpartum diabetes in the IADPSG group was not significantly different to that in the JSOG group, although the mean follow-up period was significantly longer in the JSOG group (Table 2). In addition, in women diagnosed with postpartum diabetes, the duration from the index delivery to the development of diabetes was significantly shorter in the IADPSG group than in the JSOG group. Thus, in comparison to the previous criteria, the IADPSG criteria seemed to recognize more women who develop postpartum diabetes earlier. Assaf-Balut et al. [10] reported that the change in diagnostic criteria from the Carpenters-Coustan (CC) criteria to the IADPSG criteria did not affect the percentage of women with postpartum glucose disorder (29.5% vs. 32.3%, respectively [10]. Because the number of women who were diagnosed in the IADPSG group was higher than that in the CC group, the IADPSG criteria could be superior for identifying women with postpartum glucose disorder who would have been missed by the CC criteria [10], even though the IADPSG criteria are based on only the perinatal outcomes and not on the risk of developing postpartum diabetes.

There is already evidence to show that women with a history of GDM are at significant risk for the development of type 2 diabetes; however, the follow-up tests after delivery have been suboptimal [11, 12], in spite of the current recommendations including early postpartum diabetic screening at 6–12 weeks postpartum and further follow-up tests [13,14,15]. In addition to the markedly low follow-up rates of only 16–48% that were reported in previous studies [16,17,18,19], the increase in the number of women with GDM after the adoption of the IADPSG criteria makes their postpartum follow-up screening more difficult. Under these conditions, it is very important to identify women with a high risk of developing postpartum diabetes.

A recent meta-analysis using a univariate model identified a large number of risk factors for the future progression of diabetes. These included BMI, a family history of diabetes, non-white ethnicity, advanced maternal age, an early diagnosis of GDM, the fasting and post-glucose load PG, the HbA1c level, the use of insulin, multiparity, hypertensive disorder, and preterm delivery [7]. Although we did not investigate obstetric complications, such as hypertension and preterm delivery, or the breastfeeding conditions in our study, the risk factors identified in the univariate analysis were similar to those reported in Rayanagoudar’s study [7]. There were some differences between the studies regarding maternal age, family history, multiparity and GA at the time of their diagnosis. These differences are probably due to the small sample size of our study.

After controlling for confounders in the multivariate models, we identified two independent risk factors for the development of diabetes during a relatively long-term postpartum follow-up period of five years that were present during the index pregnancy: elevated 2-h PG and HbA1c values. Several authors have reported that the HbA1c level at the diagnosis of GDM during pregnancy is an independent predictor of the development of postpartum diabetes [20,21,22]. In a Swedish study [20] of 144 women with GDM who had high risk factors, including a first-degree family history of diabetes or previous GDM, the HbA1c and fasting PG values during pregnancy were found to be independent predictors in 43 cases (30.6%) in which women developed diabetes within 5 years postpartum. They found that an HbA1c level of ≥5.7% and a fasting PG level of ≥94 mg/dl (5.2 mmol/L) were associated with a 4.8- and 6.8-fold increase in the risk of developing postpartum diabetes, respectively, in comparison to women whose HbA1c and fasting PG levels were below these cutoff values. In our study, the cutoff HbA1c value derived from the ROC was 5.6%, which is in line with that in the Swedish study. We did not find a significant association between fasting PG and diabetes; instead, 2-h PG was an independent predictor. This is probably due to several factors, including the difference in the study populations, especially the fact that the Swedish study only included high-risk women, the difference in the lengths of the follow-up periods and ethnicity [23]. Despite these differences, the HbA1c level of ≥5.7% and fasting PG level of ≥94 mg/d in the Swedish study [20], and the HbA1c level of ≥5.6% and the 2-h PG level of ≥183 mg/dl in our study were not comparable to the marked hyperglycemia that is seen in patients with pregestational diabetes. It is therefore important to consider that those modestly elevated HbA1c and glucose levels (either the fasting or the post-glucose load) during pregnancy are associated with the development of diabetes within 5 years postpartum. Several studies addressed HbA1c as a parameter for predicting postpartum diabetes in women with GDM among different races and ethnicities with different diagnostic criteria for GDM and follow-up duration [24,25,26,27]. Those studies found significant independent predictive cut-off values for the development of diabetes between 5.4% and 5.7%. Again, a modestly elevated level HbA1c seems to be a significant predictor regardless of race and ethnicity.

In our previous study, we reported that both a lower insulingenic index, which exhibits decreased early-phase insulin secretion and insulin therapy during pregnancy are independent predictors for abnormal glucose tolerance, including both prediabetes and diabetes, in the early postpartum period [5].

Because we only measured insulin in half of the subjects in the current study, we were not able to address insulin dynamics during pregnancy. Kwak et al. [28] reported the difference in the characteristics between diabetic women with a history of GDM who were diagnosed in the early and late postpartum period. Interestingly, they suggested that women with the early development of diabetes had more pronounced defects in their beta-cell function, which might be explained by differences in their genetic predisposition [28].

The major strength of this study was the relatively high follow-up rate of up to 86%, which was very similar regardless of the diagnostic criteria used. As already mentioned, the previously reported postpartum follow-up rates were less than 50%. In our study, 75% of the subjects underwent at least two follow-up OGTTs and more than 50% of them were followed up beyond 12 months after their pregnancy (Table 2).

The present study is associated with several limitations. We did not address any postpartum factors, including postpartum weight change and breastfeeding. An increase in weight during the postpartum period is known to be a significant risk factor for the development of diabetes [2, 29, 30]. Although we controlled for the baseline obesity and weight gain in pregnancy in the multivariate analysis, we did not investigate the effect of the postpartum weight changes on the development of diabetes during the follow-up period. Breastfeeding is also expected to be a predictor of the postpartum development of diabetes in the general population [31] and in women with a history of GDM [32,33,34]. However, we did not investigate this factor because we could not obtain sufficient data on the subjects’ breastfeeding practices due to the retrospective approach of our study. Because of the small sample size in this study, we were unable to conclude that other variables, including prepregnancy obesity and insulin therapy during pregnancy as well as fasting PG during the diagnostic OGTT for GDM, were not significant predictors for the development of postpartum diabetes. Because of the small sample size, we were unable to perform analyses limited to women were diagnosed under the IADPSG criteria. Although our results suggest that the IADPSG criteria are efficient at identifying women with GDM at risk of developing postpartum diabetes, further prospective cohort studies with a larger sample size are necessary to draw any definitive conclusions on this issue.

Conclusions

In conclusion, despite the diagnostic criteria, in women with a history of GDM, the elevation of the HbA1c and 2-h PG levels during pregnancy, at the time of the diagnostic OGTT, was independently associated with the development of diabetes within 5 years postpartum. Thus, to make an early diagnosis of postpartum diabetes, it is important to carefully pay attention to pregnant women with HbA1c and 2-h PG levels that are higher than the above-mentioned cutoff points of 5.6% and 183 mg/dl, respectively, despite the use of insulin.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CC:

-

Carpenters-Coustan

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- GA:

-

gestational age

- GDM:

-

gestational diabetes

- HbA1c:

-

hemoglobin A1c

- IADPSG:

-

International Society of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group

- JSOG:

-

Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology

- OGTT:

-

oral glucose tolerance test

- PG:

-

plasma glucose

- ROC:

-

receiver operating curve

- RR:

-

relative risk

- SMBG:

-

self-monitored blood glucose

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Bellamy L, Casas P, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–9.

O’Sullivan JB. Gestational diabetes: factors influencing rate of subsequent diabetes. Sutherland HW, Stowers JM (eds) In: Carbohydrate metabolism in pregnancy and the newborn. Springer-Verlag, New York, p. 429, 1978.

Matthews DR, Matthews PC. Type 2 diabetes as an ‘infectious’ disease: is this the black death of the 21st century? Diabet Med. 2011;28:2–9.

International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups. Recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:676–82.

Kugishima Y, Yasuhi I, Yamashita H, Fukuda M, Yamauchi Y, Kuzume A, Hashimoto T, Sugimi S, Umezaki Y, Suga S, Kusuda N. Risk factors associated with abnormal glucose tolerance in the early postpartum period among Japanese women with gestational diabetes. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;129:42–5.

Morikawa M, Yamada T, Yamada T, Akaishi R, Nishida R, Cho K, Minakami H. Change in the number of patients after the adoption of IADPSG criteria for hyperglycemia during pregnancy in Japanese women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90:339–42.

Rayanagoudar G, Hashi AA, Zamora J, Khan KS, Hitman GA, Thangaratinam S. Quantification of the type 2 diabetes risk in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 95,750 women. Diabetologia. 2016;59:1403–11.

The Committee on Nutrition and Metabolism of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The committee report. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Jpn. 1984;36:2055–8.

World Health Organization (2006). Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHOIDF consultation. World Health Org. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43588.

Assaf-Balut C, Bordiú E, del Valle L, Lara M, Duran A, Rubio MA, et al. The impact of switching to the one-step method for GDM diagnosis on the rates of postpartum screening attendance and glucose disorder in women with prior GDM. The San Carlos gestational study. J Diabetes Complicat. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.04.026.

McGovern A, Butler L, Jones S, van Vlymen J, Sadek K, Munro N, Carr H, de Lusignan S. Diabetes screening after gestational diabetes in England: a quantitative retrospective cohort study. Br J General Practice. 2014:e17–23.

Lawrence JM, Black ME, Hsu JW, Chen W, Sacks DA. Prevalence and timing of postpartum glucose testing and sustained glucose dysregulation after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:569–76.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Diabetes in pregnancy: management of diabetes and its complications from pre-conception to the postnatal period: NICE; 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3/chapter/1-Recommendations.

ACOG Committee opinion #435. Postpartum screening for abnormal glucose tolerance in women who had gestational diabetes mellitus. American College of Obstetricians and Gynwcologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1419–21.

Clinical Question 005-1: Diagnosis of glucose intolerance in pregnant women (in Japanese). Guidelines for Obstetrical Practice in Japan 2014 edition. Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG). 2014. pp. 19–23.

Smirnakis KV, Chasan-Taber L, Wolf M, Markenson G, Ecker JL, Thadhani R. Postpartum diabetes screening in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1297–303.

Russell MA, Phipps MG, Olson CL, Welch HG, Carpenter MW. Rates of postpartum glucose testing after gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1456–62.

Baker AM, Brody SC, Salisbury K, Schectman R, Hartmann KE. Postpartum glucose tolerance screening in women with gestational diabetes in the state of North Carolina. N C Med J. 2009;70:14–9.

Kwong A, Mitchell RS, Senoir PA, Chik CL. Postpartum diabetes screening: adherence rate and the performance of fasting plasma glucose versus oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2242–4.

Ekelund M, Shaat N, Almgren P, Groop L, Berntorp K. Prediction of postpartum diabetes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2010;53:452–7.

Eades CE, Styles M, Leese GP, Cheyne H, Evans JMM. Progression from gestational diabetes to type 2 diabetes in one region of Scotland: an observational follow-up study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0457-8.

Oldfield MD, Donley P, Walwyn L, Scudamore I, Gregory R. Long term prognosis of women with gestational diabetes in a multiethnic population. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:426–30.

Hsu WC, Boyko EJ, Fujimoto WY, Kanaya A, Karmally W, Karter A, King GL, Look M, Maskarinec G, Misra R, Tavake-Pasi F, Arakaki R. Pathophysiologic differences among Asians, native Hawaiians, and other Pacific islanders and treatment implications. Diabetes Care. 2012;3:1189–98.

Claesson R, Ignell C, Shaata N, Berntorp K. HbA1c as a predictor of diabetes after gestational diabetes mellitus. Primary Care Diabetes. 2017;11:46–51.

Liu H, Zhang S, Wang L, Leng J, Li W, Li N, Li M, Qiao Y, Tian H, Tuomilehto J, Yang X, Yu Z, Hu G. Fasting and 2-hour plasma glucose, and HbA1c in pregnancy and the postpartum risk of diabetes among Chinese women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes Rec Clin Pract. 2016;112:30–6.

Kwon SS, Kwon JY, Park YW, Kim YH, Lim JB. HbA1c for diagnosis and prognosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;110:38–43.

Bartakova V, Malúšková D, Mužík J, Bělobrádková J, Kaňková K. Possibility to predict early postpartum glucose abnormality following gestational diabetes mellitus based on the results of routine mid-gestational screening. Biochem Med. 2015;25:460–8.

Kwak SH, Choi SH, Jung HS, Cho YM, Lim S, Cho NH, Kim SY, Park KS, Jang HC. Clinical and genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes at early or late post partum after gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E744–52.

Liu H, Zhang C, Zhang S, et al. Prepregnancy body mass index and weight change on postpartum diabetes risk among gestational diabetes women. Obesity. 2014;22:1560–7.

Bao W, Yeung E, Tobias DK, et al. Long-term risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in relation to BMI and weight change among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Diabetologia. 2015;58:1212–9.

Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards AW, Willett WC, Manson JE, Michels KB. Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2005;294:2601–10.

Gunderson EP, et al. Lactation intensity and postpartum maternal glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in women with recent GDM: the SWIFT cohort. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:50–6.

Ziegler AG, Wallner M, Kaiser I, Rossbauer M, Harsunen MH, et al. Long-term protective effect of lactation on the development of type 2 diabetes in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2012;61:3167–71.

Gunderson EP, Hurston SR, Ning X, Lo JC, Crites Y, Walton D, Dewey KG, Azevedo RA, Young S, Fox G, Elmasian CC, Salvador N, Lum M, Sternfeld B, Quesenberry CP Jr, for the Study of Women, Infant Feeding and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy Investigators. Lactation and progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Ann Int Med. 2015;163:889–92.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There was no funding source for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.K., I.Y., and H.Y. wrote the initial research proposal and manuscript; Y.K., H.Y., S.Sugimi, Y.U.and S.Suga acquired data, Y.K. and H.Y., and I.Y analyzed data; M.F. and N.K. contributed to the discussion; Y.K. drafted the manuscript; I.Y. revised the manuscript and gave final approval of the version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We stated in the last paragraph of the Method section; “This study was conducted with the approval of the Institution Review Board of Nagasaki Medical Center to collect the clinical data with informed consent.”

The name of the ethics committee: The Institute Research Board of Nagasaki Medical Hospital, #28065 on Sep 5th, 2016.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kugishima, Y., Yasuhi, I., Yamashita, H. et al. Risk factors associated with the development of postpartum diabetes in Japanese women with gestational diabetes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 19 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1654-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1654-4