Abstract

Background

Surveys using questionnaires to collect epidemiologic data may be subject to misclassification. Here, we analyzed a headache questionnaire to evaluate which questions led to a classification other than migraine.

Methods

Anonymized surveys coupled with medical claims data from individuals 19–74 years old were obtained from DeSC Healthcare Inc. to examine proportions of patients with primary headache disorders (i.e.; migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, and “other headache disorders”). Six criteria that determined migraine were used to explore how people with other headache disorders responded to these questions.

Results

Among the 21480 respondents, 7331 (34.0%) reported having headaches. 691 (3.2%) respondents reported migraine, 1441 (6.7%) had tension-type headache, 21 (0.1%) had cluster headache, and 5208 (24.2%) reported other headache disorders. Responses of participants with other headache disorders were analyzed, and the top 3 criteria combined with “Symptoms associated with headache” were “Site of pain” (7.3%), “Headache changes in severity during daily activities” (6.4%), and the 3 criteria combined (8.8%). The symptoms associated with headache were “Stiff shoulders” (13.6%), “Stiff neck” (9.4%), or “Nausea or vomiting” (8.7%), Photophobia” (3.3%) and “Phonophobia” (2.5%).

Conclusions

Prevalence of migraine as diagnosed by questionnaire was much lower than expected while the prevalence of “other headache” was higher than expected. We believe the reason for this observation was due to misclassification, and resulted from the failure of the questionnaire to identify some features of migraine that would have been revealed by clinical history taking. Questionnaires should, therefore, be carefully designed, and doctors should be educated, on how to ask questions and record information when conducting semi-structured interviews with patients, to obtain more precise information about their symptoms, including photophobia and phonophobia.

Highlights

It is difficult to correctly identify “symptoms associated with headache” in a single response survey.

Surveys with questions regarding photophobia and phonophobia should be carefully designed to help headache classification.

It is necessary to educate patients to understand the symptoms of photophobia and phonophobia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Headaches represent the most prevalent of the neurological disorders worldwide, and rank among the leading causes affecting global disability-adjusted life-years [1]. In Japan, headaches are the 5th leading cause of disability in women [2]. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, version 3 (ICHD-3) classifies headaches as primary, where the headache is present in the absence of an underlying pathologic process, disease, or traumatic injury, and secondary, where the headache is due to a causative disorder [3, 4]. The most common primary headaches are migraine, tension-type headache, and cluster headache and other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias [3, 5]. Other headaches may include primary cough headache, primary exercise headache, primary headache associated with sexual activity, and primary thunderclap headache [3]. The criteria provided by the ICHD-3 has become the accepted standard for diagnosis of headaches [5], and epidemiological studies on migraine in Japan have been conducted based on this classification [6, 7].

Recent epidemiologic studies where primary headache types were based on the ICHD-3 classification provided proportions of the occurrence of these headaches, such as migraine, that were non consistent across subject populations [8, 9]. Our team recently conducted an epidemiological survey linking medical claims and online survey data in order to assess the prevalence of primary headache disorders [10, 11]. The survey classified headache based on the questions presented in the questionnaire, and the responses were used for the evaluation of migraine. In that survey, the prevalence of migraine (including suspected migraine) was 691 (3.2%), that of tension-type headache was 1441 (6.7%), that of cluster headache was 21 (0.1%), and that of other headache disorders 5208 (24.2%) [10]. These findings differ considerably from an earlier survey in Japan that reported a migraine prevalence of 8.4% and the prevalence of “other headaches” as being 8.9% [6], which was greater than expected, and is suspected to include patients with migraine or cluster headache. We, therefore, decided to analyze questionnaire items to assess which questions provided response classifications other than migraine.

Methods

This is a retrospective observational study using a database comprising medical claims data and survey data. The aim of our study, was to analyze which questionnaire items led to a classification other than migraine. Using a pre-existing survey data, headache disorders were classified into migraine, tension-type, and cluster headaches; and those that were not classified as any of these types, were classified as “other headache disorders”. In this analysis, we focused on migraine and other headache disorders.

Medical claims data and linked survey data obtained by DeSC Healthcare, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan; hereafter, DeSC). DeSC comprised the database of anonymously processed data that was provided by the Society-Managed Employment-Based Health Insurance for the period from 1 December 2017 to 30 November 2020 for subscribers who had agreed to the secondary use of medical data. The study subjects were employees, and their family members, of companies participating in Society-Managed Employment-Based Health Insurance and who were registered users of the health app “kencom®”. Kencom® is a free health monitoring app designed by DeSC that is available, either as a mobile app or via a website, to users in Japan who are members of an affiliated Society-Managed, Employment-Based Health Insurance association [12].

The questionnaire data used for this study were originally collected based on an online questionnaire containing items that were designed to be consistent with the ICHD-3 criteria for migraine and other headache disorders and were administered by DeSC via kencom® from November 1, 2020 to November 30, 2020. This survey consisted of 69 closed-ended questions, with single and multiple possible answers (Supplementary Data 1) [10, 11].

Eligibility criteria

The study population was derived from approximately 600,000 members of the health insurance association that had contracts with DeSC, and who agreed to the secondary use of medical data. From this population respondents who were aged 19 to 74 years and who were registered in kencom® were provided with online surveys. Only those persons who provided response data for the survey were included in the study. Patients included in this survey were classified as having headache based on the self-administered web questionnaire survey on headache and quality of life (QOL) and based on health insurance association medical claims data.

Outcome measures

Data were extracted from the database. Survey data included background demographic information, such as gender, age, menstruation status, prefecture of residence, occupation, and annual income. Additionally, the questionnaire items included the presence of headaches and of headache disorders, the frequency, number, and duration of the headaches and their symptoms, headache severity, disruption to daily life, and activities that are interfered with or restricted due to headache. The survey was used to determine if there was a diagnosis of migraine, the status of consultations for migraine and headache, the type of medical institution and department that was consulted, the burden of visiting medical institutions, the presence and nature of symptoms comorbid with migraine/headache, and the status of over-the-counter (OTC) headache medication, including the drug name, frequency of use, and reasons for discontinuation.

The data received from DeSC provided additional background demographic information, the presence or absence of a diagnosis code (i.e.; International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10 codes) for migraine and/or headache disorder, prescription data for headache medication and for comorbidities, and the presence or absence of diagnosis codes for comorbidities (including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, psychiatric or psychosomatic disease, epilepsy, asthma, allergy, autoimmune disease, and other diseases).

Headache classification

The classification of migraine (Supplementary Data 2) was based on the structured survey responses, including internal diagnostic criteria, as migraine with and without aura, including probable migraine in line with the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) [5]. Additionally, classification of tension-type headache (Supplementary Data 3) and cluster headache (Supplementary Data 4) were also based on the structured survey responses and classified according to ICHD-3 criteria. Individuals not classified in any of these headache types are included in other headache types.

Statistical analysis

There were 6 criteria that were used in determining migraine characteristics: Criterion 1: Duration of headache, Criterion 2: Site of pain, Criterion 3: Characteristics of pain, Criterion 4: Change in severity due to daily activities or, State when in pain, Criterion 5: Symptoms associated with headache, Criterion 6: Severity (when not taking medicines). These 6 criteria were tabulated for patients with migraine as well as how individuals who had other headache disorders responded to these questions. The criteria combinations for which there were a large number of cases with headache but were mismatched to migraine (for one, two, and three unsatisfied criteria) were tabulated.

Cases that met the eligibility criteria were included in the analysis population. In this paper we report the results of the analysis population that had headaches. In principle, categorical data are presented as the number of cases and percentage (%). For categorical data, the number of cases and the percentage (%) are shown. Continuous values were summarized by descriptive statistics (N, mean, SD, etc.). The frequency of migraine, other headache disorders were calculated as prevalence rates. The frequency of migraine and other headache disorders were calculated for each disease area distribution, age of onset, and severity. The frequencies of headache diseases, headache medications, and comorbidities, were calculated from receipt information. Statistical significance tests were not conducted. Software used for statistical analysis was SAS Release 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., NC, USA).

Ethics approval and informed consent

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Research Institute of Healthcare Data Science (approval No.: RI2020012). Additionally, this study was conducted in consideration of the Declaration of Helsinki (revised October 2013) by the World Medical Association and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. This study used only anonymized data provided by DeSC Healthcare, Inc. Moreover, as Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Clinical Study Support Inc. (CSS), and the medical experts did not possess or receive data correspondence sheets, it was impossible to identify any individual. In addition, DeSC does not have a correspondence table for the data provided to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, and it is, therefore, impossible to identify individuals from the data provided. Therefore, under the Japanese legal regulations, “Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects”, it was judged unnecessary for the study investigators to obtain new individual level consent for the use of the data in this study.

Results

Disposition of respondents

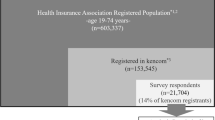

There was a total of 604,102 members of the health insurance associations who consented to the secondary use of their medical data (Fig. 1). Of these, 603,337 individuals were between the ages of 19 and 74 years, and of these, 153,545 were registered with kencom®. Of the 21,704 respondents to the survey, 224 were excluded because their age and/or gender did not match the medical claims data, leaving an analyses population of 21,480 respondents. Among the analysis population, 14,169 (66.0%) of the respondents did not have headaches, and 7311 (34.0%) had headache. There were 691 (3.2%) respondents with migraine (including probable migraine), 1441 (6.7%) who had tension-type headache (including those with probable tension-type headache), 21 (0.1%) who had cluster headache, and 5208 (24.2%) who had “other headache disorders”.

Participant demographic and Disease characteristics

Among those individuals with migraine, 272 (39.4%) were male and 419 (60.6%) were female. Among the 5208 individuals with other headache disorders, 3198 (61.4%) were male and 2010 (38.6%) were female. Most of the participants were between the ages of 30 and 59 years for both groups. There were 667 (96.5%) of participants with migraine who had a headache within the past 45 days and 5065 (97.3%) participants without migraine who reported having had a headache within the past 45 days. Within the comorbidities, gastrointestinal disorders were the most frequently reported comorbidities within the past 6 months in both groups (55.9% for migraine group and 58.1% other headache disorders group). Demographics and disease characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

The responses of the 5208 participants who were classified as other headache disorders (i.e.; other than migraine, tension-type, and cluster headaches) were analyzed to determine which of these criteria had larger percentages of participants who did not match the criteria for migraine based on the questionnaire (Table 2). Among those who had 1 criterion unsuitable, Criterion 5 (Symptoms associated with headache) was mismatched by the largest proportion of participants (52.5%), followed by Criterion 2 (Site of pain: 15.3%), and Criterion 4 (Headache changes in severity during daily activities: 8.7%). The following are the top 3 combinations of criteria in which participants did not match two or more of the criteria in the ICHD-3 questionnaire, along with the percentage of participants for each combination, are:

-

Criterion 5 (Symptoms associated with headache) AND Criterion 2 (Site of pain) AND Criterion 4 (Headache changes in severity during daily activities); 8.8%.

-

Criterion 5 (Symptoms associated with headache) AND Criterion 2 (Site of pain); 7.3%.

-

Criterion 5 (Symptoms associated with headache) AND Criterion 4 (Headache changes in severity during daily activities); 6.4%.

Among the choices for the symptoms that were associated with Criterion 5 (Symptoms associated with headache: Table 3), “Photophobia” (3.3%) and “Phonophobia” (2.5%) were less common than “Stiff shoulders” (13.6%), “Stiff neck” (9.4%), or “Nausea or vomiting” (8.7%).

Discussion

In the results of this study, 3.2% of respondents had migraine (including probable migraine), and 6.7% of respondents had tension-type headache (including those with probable tension-type headache). These values are considerably lower than the population prevalences which have been reported as 8.4% for migraine [6], and 15.6% for tension-type headache [6]. We believe that the relatively low prevalence of migraine and tension-type headache reported in this study was due to misclassification and resulted from the failure of the questionnaire to identify some features of migraine and tension-type headache that would have been revealed by clinical history taking. Questionnaires should, therefore, be carefully designed, and doctors should be educated on how to ask questions and record information when conducting semi-structured interviews with patients, to obtain precise information about their symptoms, including photophobia and phonophobia.

The present study assessed the criteria that participants selected in describing the properties of their headaches in an effort to determine the type of headache that was experienced by the participant. It is possible that participants in all these other headache disorders do not actually have migraine, but without a physician’s interview, there remains a possibility that the wording or expression of the questions may have led to the classification of other headache disorders. The choice of “unilateral” for Criterion 2 – ‘Site of pain’ – is consistent with migraine, and is one of the diagnostic criteria according to ICHD-3, as one case in point [3]. There are reasons why this criterion (Site of pain) also overlapped with participants with other headache disorders. Participants who have experienced headache episodes over a long period of time may not have been able to choose just one possible item for this criterion (Site of pain), since the sites of the headaches can change when disease duration is long. Moreover, the phenotype of migraine can change over time with the age of the patient and the duration of the disease [13]. For example, one study suggested that the proportion of migraine attacks may decrease with age along with a proportionate increase in attacks of tension-type headaches [13, 14]. In addition, transformation of episodic to chronic migraine can include a pattern of headaches that resemble tension-type headaches [13]. Thus, it may have been difficult for participants with long-duration headache disorder to answer this question in the survey. There is overlap among the different populations experiencing different types of headaches [15]. Patients who have had multiple type of headaches in the past may have difficulty with this criterion (Site of pain) as well. We suggest that when such a questionnaire is administered, or when an interview is conducted by non-specialists, to participants who have had a long duration of headache episodes, it would be helpful to ask about the type and location of headache they have experienced, including if the pain is still continuing at the same location as they have answered in a questionnaire or an interview.

There are possible reasons why the responses to the question Criterion 4 – “Headache changes in severity during daily activities” may be categorized with other headache disorders. A patient may experience more than one type of headache [15], and therefore could not respond accurately. In actual clinical practice, the symptoms associated with headache are taken into account in making the diagnosis of the type of headache. However, this is difficult to do when presenting a uniform questionnaire. Another possible reason is that patients who have experienced multiple headaches may have difficulty into classifying them as one headache because the headache pain could become better or worse by daily activities.

For “nausea“, the response choice of ‘Symptoms associated with headache,’ it will be necessary to ask in detail whether the patient has “upset stomach,” “loss of appetite,” “slight yawn,” etc., because the patient may select “nausea” only when the symptoms are very severe. One possible reason for the lower response rate in participants with migraine to Criterion 5 “photophobia/phonophobia”, under ‘Symptoms associated with headache’ than in past reports [16] may be that respondents had difficulty answering the question and were not confident to select this response. In a study conducted in Japan of outpatients with migraine using semi-structured interviews, 76.5% of patients reported phonophobia and 75.4% reported photophobia [16]. We proposed that, when addressing the symptom of photophobia, the questions should be specific, such as “Do you dim the lights in your room?,” “Do you find it easier when the curtains are closed?,” or “Do you mind the afternoon sun?” Regarding the phonophobia, it will be better to ask questions with specific examples, such as, “When you have a headache, does it bother you if you hear a banging sound, etc.?” or “Do you feel uncomfortable when the TV is on?”

A survey using a comprehensive health literacy questionnaire administered to Japanese participants found that Japanese health literacy is lower than that of Europeans [17]. The authors suggested that this discrepancy may be due in part by certain inefficiencies in the system, and that there is no comprehensive national online platform, making it difficult for Japanese participants to access reliable and understandable health information [17]. Thus, it is possible that Japanese participants may be less familiar with the terms “photophobia” and “phonophobia” than migraine patients may be in other countries. Since the present population is comprised of health insurance association members, their level of knowledge is likely to be higher than that of the general population, but even so, they were not able to successfully answer whether they were photophobia or phonophobia. It is believed that disease awareness was found to be associated with photophobia and phonophobia, among other factors [18]. Improved self-awareness regarding migraine and other headache disorders and of associated symptoms is needed. Because of the diversity of Japanese expressions [19], it is important for non-specialists to distinguish the words appropriately when they conduct a semi-structured interview to diagnose headache. For this purpose, it may be preferable to create a diagnostic tool.

Limitations

The survey was administered to current employees of companies covered by DeSC contracted health insurance associations or their family members. Members of health insurance associations were large companies with many employees and therefore the survey did not include self-employed workers, civil servants, employees of small and medium-sized companies, or the retired elderly. Employees of companies were expected to have a relatively high socioeconomic status and lived in areas with good medical access and were limited to certain occupations. Thus, there are limitations to generalizing the results of the population in this study to all Japanese adults.

The participants who were targeted to receive the questionnaire were limited to those who were registered users of kencom®. These users tend to be more health-conscious than non-users and more likely to be engaged in healthy living. In general, health-conscious individuals tend to have better health outcomes, thus selection bias may have occurred by underestimating outcomes such as prevalence, resulting in limiting the generalizability.

The survey items of the study were based primarily on self-reported information collected as the questionnaire response, therefore, the ability to recall past medical and prescription histories may have been limited, and the accuracy of the measurement may have been limited. To address this, we obtained highly accurate information on drug prescriptions from the claims data, rather than from the questionnaire. The items related to the physician visit for headache were also evaluated using the claims data as well as the questionnaire. Meanwhile, medical claims data are subject to misclassification because the injury and disease names in the claims data are also insurance disease names for the purpose of medical fee billing.

Conclusions

When migraine classification was conducted using only a questionnaire without a semi-structured interview, it was clear that some items enabled classification and some items resulted in classification as other than migraine. In the present self-administered online survey, the migraine criterion about symptoms was not satisfied by many of the respondents classified as having other headache disorders, and even by most respondents categorized as having migraine. The results suggest that to capture the subjective and varying experience of headache, particularly symptoms including photophobia and phonophobia, it may be important to carefully devise the survey to help headache classification. In addition, it is necessary to educate patients about headache symptoms so that they understand the symptoms of photophobia and phonophobia. There is also a need for some kind of education for doctors on how to record information when interviewing patients in order to better obtain more precise information about their symptoms.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from DeSC Healthcare, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of DeSC Healthcare, Inc.

Abbreviations

- ICHD-3:

-

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, version 3

- OTC:

-

Over-the-counter

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

References

Feigin VL, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abd-Allah F, Abdulle AM, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:877–97.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. III. Household health conditions. In: 2019 Comprehensive survey of living conditions [in Japanese]. 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa19/dl/04.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2008.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211.

Mier RW, Dhadwal S. Primary headaches. Dent Clin North Am. 2018;62:611–28.

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Steiner TJ, Silberstein SD, Olesen J. Classification of primary headaches. Neurology. 2004;63:427–35.

Sakai F, Igarashi H. Prevalence of migraine in Japan: a nationwide survey. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:15–22.

Takeshima T, Ishizaki K, Fukuhara Y, Ijiri T, Kusumi M, Wakutani Y, et al. Population-based door-to-door survey of migraine in Japan: the Daisen study. Headache. 2004;44:8–19.

Hirata K, Ueda K, Komori M, Zagar AJ, Selzler KJ, Nelson AM, et al. Comprehensive population-based survey of migraine in Japan: results of the ObserVational Survey of the epidemiology, tReatment, and care of MigrainE (OVERCOME [Japan]) study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37:1945–55.

Kikui S, Chen Y, Todaka H, Asao K, Adachi K, Takeshima T. Burden of migraine among Japanese patients: a cross-sectional National Health and Wellness Survey. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:110.

Sakai F, Hirata K, Igarashi H, Takeshima T, Nakayama T, Sano H, et al. A study to investigate the prevalence of headache disorders and migraine among people registered in a health insurance association in Japan. J Headache Pain. 2022;23:70.

Hirata K, Sano H, Kondo H, Shibasaki Y, Koga N. Clinical characteristics, medication use, and impact of primary headache on daily activities: an observational study using linked online survey and medical claims data in Japan. BMC Neurol. 2023;23:80.

Hamaya R, Fukuda H, Takebayashi M, Mori M, Matsushima R, Nakano K, et al. Effects of an mHealth app (Kencom) with Integrated functions for healthy lifestyles on physical activity levels and Cardiovascular Risk biomarkers: Observational Study of 12,602 users. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e21622.

Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Concepts and mechanisms of migraine chronification. Headache. 2008;48:7–15.

Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Sheftell FD, Tepper SJ, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine is an earlier stage of transformed migraine in adults. Neurology. 2005;65:1556–61.

Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olesen J. Interrelations between migraine and tension-type headache in the general population. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:914–8.

Suzuki K, Suzuki S, Shiina T, Okamura M, Haruyama Y, Tatsumoto M, et al. Investigating the relationships between the burden of multiple sensory hypersensitivity symptoms and headache-related disability in patents with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2021;22:77.

Nakayama K, Osaka W, Togari T, Ishikawa H, Yonekura Y, Sekido A, et al. Comprehensive health literacy in Japan is lower than in Europe: a validated japanese-language assessment of health literacy. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:505.

Radtke A, Neuhauser H. Low rate of self-awareness and medical recognition of migraine in Germany. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:1023–30.

Takeuchi K, Aoki S, Suzuki S. [Adequacy of translating health survey questionnaires for cross-cultural surveys–the case of the Todai Health Index] [in Japanese]. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 1993;40:653–9.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). The statistical analysis was supported by Tatsuo Sakashita and Tetsumi Toyoda, Clinical Study Support Inc. (Nagoya, Japan) and medical writing, editing and formatting of the manuscript was supported by Kyoko Inuzuka, Clinical Study Support Inc. (Nagoya, Japan) and Michael Ossipov of Evidera-PPD (New York, USA) under contract and paid for by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., (Osaka, Japan). Data management and extraction was supported by Akiko Hatakama from DeSC Healthcare Inc. (Tokyo, Japan).

Funding

This work was sponsored and funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. played a specific role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript. Additionally, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. contracted DeSC Healthcare Inc. for data management and extraction services, and Clinical Study Support., Inc. for statistical analysis, and Clinical Study Support., Inc. in collaboration with Evidera-PPD for writing and editorial services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TT, KH, HI, FS, HS, HK, YS, and NK contributed to the conception and design of the work; played a role in either drafting the work and in substantively revising it. Additionally, TT, KH, HI, FS, HS, HK, YS, and NK contributed to and have approved the submitted version (and any substantially modified version that involves the author’s contribution to the study).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Clinical trial no., ethics approval, and consent to participate declaration

This study was conducted as an observational study. This study was not, therefore, registered as a clinical trial with the regulatory authorities, and there is no applicable “Clinical Trial Number”.

This study used only anonymized data provided by DeSC Healthcare, Inc. Moreover, as Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Clinical Study Support Inc. (CSS), and the medical experts did not possess or receive data correspondence sheets, it was impossible to identify any individual subject. In addition, DeSC does not have a correspondence table for the data provided to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, and it is, therefore, impossible to identify individual subjects from the data provided. Therefore, under the Japanese legal regulations, “Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects”, it was judged unnecessary for the study investigators to obtain new individual level consent for the use of the data in this study.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Research Institute of Healthcare Data Science (approval No.: RI2020012), who on the above stated information judged that the need for consent to participate was deemed unnecessary according to national regulations. Additionally, this study was conducted in consideration of the Declaration of Helsinki (revised October 2013) by the World Medical Association and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

HS, HK, YS and NK are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. TT received consulting fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., during the conduct of the study; consulting fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Hedgehog MedTech, Inc., and Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; honoraria for lectures from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Amgen Inc., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., and DAIICHI SANKYO Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work; Clinical trials, contract research and collaborative research funding from Eisai Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Biohaven Ltd., and Lundbeck Japan K.K. KH received consulting fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., during the conduct of the study; consulting fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Amgen Astellas BioPharma K.K., Lundbeck Japan K.K., and Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; lecture Honoraria from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Eisai Co., Pfizer Japan, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., MSD Co., Ltd., Amgen Astellas BioPharma K.K., Ltd., and Lundbeck Japan K.K., outside the submitted work. HI received consulting fees Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., during the conduct of the study; consulting fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Daiichi Sankyo Co., Eli Lilly Japan K.K, lecture honoraria from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K, Amgen K.K., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., and Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd.; manuscript writing fee from Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; educational event fees from Lundbeck Japan K.K., outside the submitted work. FS received consultant fee from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., during the conduct of the study; consulting fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli-Lilly Co., Ltd., and Amgen Co. Ltd.; lecture Honoraria from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli-Lilly Co., Ltd., and Amgen Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Takeshima, T., Hirata, K., Igarashi, H. et al. A study to investigate the prevalence of headache disorders and migraine conducted using medical claims data and linked results from online surveys: post-hoc analysis of other headache disorders. BMC Neurol 24, 176 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03675-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03675-3