Abstract

Background

Spinal adhesive arachnoiditis is a chronic inflammatory process of the leptomeninges and intrathecal neural elements. The possible causes of arachnoiditis are: infections, injuries of spinal cord, surgical procedures and intrathecal administration of therapeutic substances or contrast.

Case presentation

We present a case of 56-old woman with spinal muscular atrophy type 3 who developed a severe back pain in the lumbosacral region after the fifth dose of nusinersen given intrathecally. Magnetic resonance of lumbosacral spine showed spinal adhesive arachnoiditis. She received high doses of methylprednisolone intravenously, and later non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, alpha lipoic acid, vitamins and rehabilitation with slight improvement.

Conclusions

The authors summarize that scheduled resonance imaging of the lumbosacral spine may be an important element of the algorithm in the monitoring of novel, intrathecal therapy in patients with spinal muscular atrophy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spinal adhesive arachnoiditis (SAA) is an inflammatory process of the arachnoid membrane which encases nerve roots. The possible etiologic factors of SAA include infections, spinal cord injury, spine surgery and intrathecal administration of contrast agents or therapeutic substances [1, 2]. Diagnosis of SAA is made based on clinical presentation and MRI. SAA treatment is difficult and often ineffective. Conservative therapy involves high-dose corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [3].

Case presentation

The patient gave her written informed consent for the case publication, and has been offered the opportunity to review the manuscript before submission.

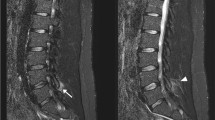

A 56-year-old woman with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 3, who had been treated with intrathecal administration of nusinersen for 9 months, was admitted to the Neurological Department with severe back pain in the lumbosacral region radiating to her left leg. The pain started after she received the last (fifth) dose of nusinersen. She never had lumbar puncture before starting the intrathecal treatment, nor any infections, injuries or surgical interventions. Neurological examination revealed increased paravertebral muscle tone and walking deterioration due to pain. Otherwise, the neurological state was unchanged compared to the examination performed three months earlier. In particular, no sensory disturbance, sphincter dysfunction or Lasegue’s sign were found. MRI of lumbosacral spine showed that the nerve roots were distorted and adherent to the thecal sac, creating the characteristic “empty thecal sac” sign. Enhancement of the nerve roots was observed following the administration of contrast. MRI also demonstrated changes of paravertebral soft tissues in the region of previous lumbar punctures (Fig. 1). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was mildly elevated (14 mm), high sensitivity C-reactive protein level was normal. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was within the normal range. Based on the symptoms and the MRI, the patient was diagnosed with adhesive arachnoiditis. Initially, she received high doses of methylprednisolone intravenously (1 g daily for 5 days) and galantamine in intramuscular injections. She was prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (diclofenac, indomethacin), alpha lipoic acid, vitamins (B1, B2, B6, D and E) and rehabilitation. Six and twelve weeks later, the patient reported persistent back pain of lower intensity without radiation to the left leg. MRIs were similar to the previous one. As a consequence the patient discontinued the therapy. The described adverse reaction was reported, in accordance with the procedure, to the local pharmacovigilance authorities, and to the pharmaceutical company.

Discussion and conclusion

SMA is a rare neuromuscular disease caused by mutation of the SMN1 gene leading to progressive weakness and atrophy of muscles. Nusinersen was approved by US Food and Drug Administration in December 2016 and is the first treatment for SMA [4]. It is administered as an intrathecal bolus injection by lumbar puncture with 4 loading doses and then once every 4 months. The most common adverse reactions are associated with the lumbar puncture procedure (e.g. headache, back pain) [5]. SAA has not been reported after intrathecal administration of nusinersen yet [6]. Several intrathecal medical substances were described as potential etiological factors of SAA with one of the major causes being the contrast agents introduced into the subarachnoid space for myelography. Intrathecal administration of amphotericin B, methotrexate, anesthetic agents and steroids has also been reported to provoke inflammation of the arachnoid membrane [1].

The clinical manifestation ranges from subclinical to advanced forms of the disease. In many cases it can be asymptomatic and remain undiagnosed. The true incidence of SAA is therefore hard to determine and is reportedly underestimated [1, 2, 7].

Due to the inflammatory process, the nerve roots become adherent to each other and to the thecal sac. On the basis of the characteristic morphological appearance on MR imaging, SAA has been divideed into three types. In type I, the nerve roots are clumped together and form a central conglomeration. In type II, the nerve roots are distorted and adherent to the thecal sac, creating the “empty thecal sac” sign as we present in our case. In type III, a large central soft-tissue mass fills the thecal sac as a result of the nerve roots clumping up with the thecal sac [8].

In the presented case, the most probable cause of SAA are the repeated lumbar punctures combined with the drug administration. The advanced vertebral column deformities in the course of SMA could additionally lead to creating favorable conditions for SAA development. SAA may be secondary to abnormal anatomical conditions of the spine, as is seen in patients with SMA, sometimes with very significant severity. Activation of inflammatory processes, primary and secondary, with subsequent ischaemia and scarring of spinal canal structures, also appears to be important in the pathogenesis of SAA. Genetic predisposition to the formation of abnormal fibrinolytic scars should be taken into account in the development of SAA [1, 2, 9]. The authors also consider the possibility of a generalized inflammatory process with activation of systemic pro- and anti-inflammatory factors, which, however, requires further study.

In the conclusion the authors indicated that spinal adhesive arachnoiditis may be a possible, significant adverse reaction after intrathecal administration of nusinersen. Scheduled resonance imaging of the lumbosacral spine may be an important element of the algorithm in therapy monitoring and may allow the diagnosis of early forms of SAA.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- SAA:

-

spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- SMA:

-

spinal muscular atrophy

- SMN:

-

survival motor neuron

References

Esses SI, Morley TP. Spinal arachnoiditis. Can J Neurol Sci. 1983;10:2–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0317167100044486.

Krätzig T, Dreimann M, Mende KC, Königs I, Westphal M, Eicker SO. Extensive spinal adhesive arachnoiditis after extradural spinal infection-spinal dura mater is no barrier to inflammation. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:1194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.05.219.

Kalina J, Arachnoiditis J, Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2012;26:176–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/15360288.2012.671239.

Ottesen EW. ISS-N1 makes the first FDA-approved drug for spinal muscular atrophy. Transl Neurosci. 2017;8:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/tnsci-2017-0001.

Walter MC, Wenninger S, Thiele S, Stauber J, Hiebeler M, Greckl E, et al. Safety and treatment effects of nusinersen in longstanding adult 5q-SMA type 3 - a prospective observational study. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2019;6:453–65. https://doi.org/10.3233/JND-190416.

Coratti G, Cutrona C, Pera MC, Bovis F, Ponzano M, Chieppa F et al. (2021) Motor function in type 2 and 3 SMA patients treated with Nusinersen: a critical review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2021;16:430–442, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-02065-z.

Burton CV, Lumbosacral arachnoiditis. Spine. 1978;3:24–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-197803000-00006.

Kunam VK, Velayudhan V, Chaudhry ZA, Bobinski M, Smoker WRK, Reede DL. Incomplete cord syndromes: clinical and imaging review. Radiographics. 2018;38:1201–22. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2018170178.

Maillard J, Batista S, Medeiros F, et al. Spinal Adhesive Arachnoiditis: A literature review. Cureus. 2023;15(1):e33697. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33697.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgements.

Funding

Supported by Wroclaw Medical University SUBZ.C220.23.073.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.U.- data collection, manuscript preparation, M.K.- study design, manuscript preparation, corresponding author, J.B. – neuroimage performance of neuroimaging tests and their interpretation, S.B. – study design, manuscript correction.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Consent for publication

From the patient described written informed consent for publication has been obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ubysz, J., Koszewicz, M., Bladowska, J. et al. Spinal adhesive arachnoiditis in an adult patient with spinal muscular atrophy type 3 treated with intrathecal therapy. BMC Neurol 24, 43 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03543-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03543-0