Abstract

Background

Microglial activation contributes to both inflammatory damage and repair in experimental ischemic stroke. However, because of the logistical challenges, there have been few clinical imaging studies directly describing inflammatory activation and its resolution after stroke. The purpose of our pilot study was to describe the spatio-temporal profile of brain inflammation after stroke using 18kD translocator protein (TSPO) positron emission tomography (PET) with magnetic resonance (MR) co-registration in the subacute and chronic stage after stroke.

Methods

Three patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and PET scans with TSPO ligand [11C]PBR28 15 ± 3 and 90 ± 7 days after an ischaemic stroke. Regions of interest (ROI) were defined on MRI images and applied to the dynamic PET data to derive regional time-activity curves. Regional uptake was quantified as standardised uptake values (SUV) over 60 to 90 min post-injection. ROI analysis was applied to identify binding in the infarct, and in frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes and cerebellum excluding the infarcted area.

Results

The mean age of participants was 56 ± 20.4 years and mean infarct volume was 17.9 ± 18.1 ml. [11C]PBR28 showed increased tracer signal in the infarcted area compared to non-infarcted areas of the brain in the subacute phase of stroke (Patient 1 SUV 1.81; Patient 2 SUV 1.15; Patient 3 SUV 1.64). [11C]PBR28 uptake returned to the level of non-infarcted areas at 90 days Patient 1 SUV 0.99; Patient 3 SUV 0.80). No additional upregulation was detected elsewhere at either time point.

Conclusions

The neuroinflammatory reaction after ischaemic stroke is limited in time and circumscribed in space suggesting that post-ischaemic inflammation is tightly controlled but regulatory mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is a substantial unmet medical need for therapies that improve outcome after ischaemic stroke. Experimental studies suggest that inflammatory processes contribute to secondary injury after brain ischaemia [1, 2]. Brain injury following transient or permanent focal cerebral ischaemia develops from a complex series of pathophysiological events that evolve in time and space [3]. Focal cerebral ischaemia induces a time-dependent recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, T cells, and monocytes/macrophages [4, 5].

The microglia are activated within hours after ischaemia-onset and secrete proinflammatory cytokines, which increase brain damage. Subsequently, microglia produce anti-inflammatory and neurotrophic factors that promote regeneration and plasticity [6, 7]. The translation of promising preclinical studies addressing neuroinflammatory targets into the clinical setting has been unsuccessful so far [7]. One major limitation to their translation has been the limited understanding of the timing of inflammatory mechanisms and their anatomic distribution in the human brain after stroke.

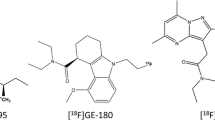

Positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracers have been developed as noninvasive molecular imaging tools to assess neuroinflammation [8]. Translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO), previously known as the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor, is present mainly in the mitochondrial compartment and can be imaged in vivo using PET [9]. TSPO is overexpressed by microglia and monocyte-derived cells during inflammation and has been extensively used as a measure of inflammation in numerous neurological diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis [9,10,11,12].

The first non-benzodiazepine-type compound to be radiolabeled was PK11195 ([11C]PK-11195) [13]. As a selective radioligand of TSPO it has been used to study the magnitude of inflammation after acute ischaemic stroke in patients [14,15,16,17,18] but several methodological issues have limited the usefulness of this radioligand [8]. Subsequently, second generation TSPO radiotracers with more favourable pharmacokinetic properties, including [11C]PBR28, have been developed. This has resulted in a substantially improved signal-to-noise ratio [19]. Thus far, only a small number of studies have examined TSPO tracer binding in co-registration with MRI-based structural imaging data to depict the anatomical distribution of tracer binding relative to the infarct [17, 18]. Moreover, insights into the temporal course of tracer binding are limited.

The purpose of our pilot study was to describe the activation of microglia by in vivo brain expression of TSPO using [11C]PBR28 PET imaging co-registered with MRI structural imaging in the subacute and chronic stages after ischaemic stroke.

Methods

Patients with clinically and radiologically defined supratentorial ischaemic stroke within the previous 10 days were studied sequentially at 15 ± 3 and 90 ± 7 days after the event. To be included, patients had to: understand the purpose and risks of the study; provide informed consent; and give authorization for the use of their protected health information. These processes were carried out in accordance with national and local subject privacy regulations and following local institutional review board’s (IRB’s)/ethics committee’s (EC’s) guidelines. The severity of neurological signs was rated according to the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). The Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) was used to assess the level of functional independence. Key exclusion criteria included the presence of acute intracranial haemorrhage on acute brain imaging; contraindications for undergoing MRI examination (including metal foreign bodies, cardiac pacemakers, renal impairment that contraindicates gadolinium) or PET scan; females who were pregnant, nursing, or planning to become pregnant during study participation; patients carrying genetic polymorphism consistent with low TSPO binding affinity. Additionally, patients were excluded if they had participated in a research or medical protocol in the previous 12 months which involved nuclear medicine, PET or radiological investigations with radiation exposure that, when combined with the radiation exposure from the present study, would exceed 10 mSV in addition to the natural background radiation. All scans were performed at the Invicro-London clinical imaging centre at Hammersmith Hospital Campus, Imperial College London.

PET procedure

[11C]-PBR28 was prepared by reacting [11C]-methyl iodide with PBR28 precursor, 4-[N-Acetyl-N-[2-methoxybenzyl]amino]-3-phenoxypyridine. The Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) grade precursor was supplied by Pharmasynth with specification set to “ > 95%” for purity (as measured by HPLC). [11C]-PBR28 was formulated in 11 mL of maximum 9% (v/v) ethanol in 0.9% saline solution for injection. The automated synthetic procedure of [11C]-PBR28 was developed in-house using an Eckert and Ziegler Modular Lab system coupled with a semi-preparative HPLC system. The product was radiochemical pure before all injections.

Subjects were positioned in the PET scanner after the insertion of a venous cannula in an antecubital or forearm vein. A head-fixation device was used to minimise head movement during data acquisition. All dynamic [11C]-PBR28 PET scans were acquired on Siemens PET/CT scanners; either a Biograph 6 or a Biograph 6 TruePoint with TrueV PET/CT scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). A low-dose CT scan was performed immediately before each PET study to estimate attenuation. Following intravenous bolus injection of the radiotracer, dynamic emission data were acquired for 90 min (frame durations: 8 × 15 s, 3 × 60 s, 5 × 120 s, 5 × 300 s, 5 × 600 s) for all scans except one (which was aborted at 79 min at the subject’s request). The dynamic images were reconstructed using Fourier rebinning and a 2D filtered discrete inverse Fourier transform algorithm with 5 mm isotropic Gaussian filter on a 128 × 128 matrix with 2.6 zoom giving 2 mm isotropic voxels. Corrections were applied for attenuation, randoms and scatter.

MRI procedure

MRI acquisitions were carried out on a Siemens 3 T MRI scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). To assess the size and location of the infarct, diffusion-weighted images (DWI, using a b-factor of 1,000 s/mm2) and T2-FLAIR-weighted images (repetition time 5000 ms; echo time 387 ms; 192 slices) were acquired. T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequences were acquired with the following parameters: repetition time 2,300 ms; echo time 2.98 ms; flip angle, 9; 160 slices. Each study participant received 0.2 ml/kg dose of gadolinium (Dotarem 0.5 mmol/ml solution).

Image analysis

The location and extent of the index brain infarcts were initially identified on routine clinical DWI MR images. The clinical MR images (T1, DWI and T2 FLAIR) performed during the hospital admission were inspected and compared with the research scans performed to exclude any stroke recurrence in between. The ischaemic infarct was delineated manually using MRICroN software (version 12/2009; C. Rorden) [20] in native space to obtain the volume taking into account the location and extent of the region(s) identified in the original DWI, and FLAIR images. Pre- and post-gadolinium T1-weighted images were compared in order to assess enhancement.

T1 MPRAGE images underwent grey matter segmentation and were co-registered to a standard reference space (MNI152;) [21]. The MNI52 template brain image and associate atlas (CIC atlas) was nonlinearly warped to the subject’s MR image to enable automated definition of other regions of interest (ROIs), including frontal lobe, temporal lobe, parietal lobe, occipital lobe and cerebellum in the left and right hemisphere and bilateral ROIs merged together with the exclusion of the territory involved in the infarct. The manually drawn ischemic infarct ROI was aligned with the subject’s T1 MPRAGE via registration of the T2 FLAIR to the T1 MPRAGE image. The aligned infarct ROI image was applied as a mask to remove the infarct region from the atlas-derived regions (such as frontal lobe).

Dynamic PET images were registered to each subject’s MRI scan and corrected for motion using a frame-to-frame registration process with a normalised mutual information cost function. ROIs defined on the MRI images were applied to the dynamic PET data to derive regional time-activity curves (TACs). Regional uptake was quantified as standardised uptake values (SUV) over the period from 60–90 min post-injection. SUV ratio (SUVR) values were also calculated, using cerebellum as the reference.

Results

Three patients (2 female, 1 male) with a supratentorial acute ischemic stroke were included in the study (Supplemental Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 56 ± 20.4 years. The mean NIHSS score on original admission was 9 ± 4.6. The mean infarct volume was 17.9 ± 18.1 ml. None of the patients had clinical signs of infection or raised inflammatory parameters during the acute stage, and on the days of baseline and follow-up images.

Patient 1 had been treated with mechanical thrombectomy because of a right M1 occlusion resulting in right middle cerebral artery infarcts. The first scanning session was performed twelve days after the stroke when her NIHSS was 1 (residual mild dysarthria) and her mRS was 1. The [11C]PBR28 PET scan of the patient revealed an increased PBR28 signal corresponding to the infarcted area on T2 FLAIR images (Fig. 1). Post-contrast T1w imaging revealed enhancement in a part of the infarct. The SUV and SUVR values were increased in the infarcted area compared to the ROIs that included the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, parietal lobe, occipital lobe and cerebellum in the left and right hemisphere and compared to the bilateral ROIs merged together with the exclusion of the territory involved in the infarct (Table 1) (Supplemental Table 2 and 3). The second scanning session was performed at ninety-seven days following the stroke when NIHSS and mRS scores remained unchanged. The increased PBR28 signal was no longer visible in the infarcted areas in the second [11C]PBR28 PET scan (Fig. 1); the SUV and SUVR values of the infarcted areas were similar to those in other predefined ROIs remote from the stroke (Table 1) (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

P1. The T2 FLAIR and the post contrast T1 MPRAGE images (A, B, D, E) showed right middle cerebral artery and anterior cerebral artery infarcts. The [11C]PBR28 PET scan illustrated an increased PBR28 signal corresponding to the core stroke areas (C, F) at 12 days after the stroke. At 97 days after the stroke the [11C]PBR28 PET scan showed that the PBR28 signal in the infarcted areas was disappeared (I, N). P2. The T2 FLAIR and the post contrast T1 MPRAGE images showed the stroke core area (A, B) and the [11C]PBR28 PET scan showed an increased PBR28 signal corresponding to the core stroke area at 16 days after the stroke (C). P3. The T2 FLAIR and the post contrast T1 MPRAGE images (A, B) the stroke core area. The [.11C]PBR28 PET scan showed an increased PBR28 signal (C) corresponding to the core stroke area identified. At 95 days following the stroke the PBR28 signal in the infarcted area disappeared (F)

Patient 2 experienced a right middle cerebral artery infarct predominantly in the territory of the peripheral lenticular striate vessels. The first scanning session was performed sixteen days after the stroke, when her NIHSS was 2 (left minor facial palsy and drift of her left leg) and her mRS was 1. The [11C]PBR28 PET scan showed an increased PBR28 signal corresponding to the infarcted area as identified on T2 FLAIR (Fig. 1). The SUV and SUVR values corresponding to the infarct were increased when compared to the predefined ROIs (Table 1) (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). Patient 2 subsequently declined undergoing the second scanning session.

Patient 3 suffered an acute occlusion of the M1 segment of the right middle cerebral artery for which he was treated with intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy. The first scanning session was performed fifteen days after the stroke, when his NIHSS was 0 and his mRS was 0. The PET scan visibly demonstrated an increased [11C]PBR28 uptake (Fig. 1), also measured by SUV and SUVR in the infarct areas compared to the predefined ROIs (Table 1) (Supplementals Table 2 and 3). The observed increased PBR28 signal corresponded to the infarct as identified on T2 FLAIR images (Fig. 1).

The second scanning session was performed 95 days following the stroke. His NIHSS was unchanged, but his mRS was 1. Elevated PBR28 signal in the infarcted areas was no longer visible (Fig. 1). The [11C]PBR28 uptake measured by SUV and SUVR in the infarcted area returned to values observed in other predefined ROIs outside the infarct (Table 1) (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

The key findings of our pilot study are that the TSPO ligand [11C]PBR28 showed a transient increased signal, only within the infarcted area, in the subacute phase of stroke and that this evidence of circumscribed glial activation resolved within 90 days.

Previous TSPO PET studies documented an increased early uptake of PK11195, a first generation TSPO ligand, in the infarct zone and suggested increases in binding up to 30 days after stroke [14, 15, 22]. Using the second generation TSPO tracer [11C]vinpocetine, Gulyás and colleagues measured the regional changes of TSPO in the brain of nine ischemic stroke patients up to 14 weeks after the insult. The authors reported increased radioligand uptake in both the ischaemic core and the peri-infarct zone [22].

The radioligand [11C]PBR28 has higher specific and lower nonspecific binding to TSPO than the first generation radioligands [8]. Hence, it is capable of assessing the local accumulation of CNS resident inflammatory cells (primarily microglial and astrocytes) with high sensitivity and specificity and to localise inflammation relatively precisely. With preclinical PET, its use for mapping the inflammatory response to relatively small areas such as the peri-ischemic penumbra in a rat stroke model, was validated [23]. In a single case study, Kreisl and colleagues described an unusual occurrence of stroke presenting as an incidental finding of increased binding of [11C]PBR28 in the right basal ganglia on PET imaging [24,25,26]. The patient was a 42-year-old man that subsequently recalled a previously unreported episode of mild weakness in his left face and left hand that occurred 12 days before the PET scan and had resolved completely within twenty-four hours. His brain MRI showed only occasional foci of mild chronic white matter ischemia but was otherwise unremarkable.

Our study is the first to sequentially study the pattern of [11C]PBR28 over a period of 90 days in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Our findings provide scientific rationale to support that TSPO imaging provides a valuable tool to study the neuroinflammatory response in stroke and allows for assessment of immunomodulatory treatments targeting inflammation in pre-clinical and clinical settings. The possibility that increased [11C]PBR28 signal within the infarct borders is a result of increased post-ischaemic blood–brain barrier permeability is contradicted by the observation that post-contrast enhancement on T1w MR images persisted in patient 3 at 90 days whereas increased tracer signal had subsided. Moreover, previous studies revealed that the degree of microglial activation appeared to be directly correlated with the degree of white matter fibre damage on MRI, which persisted in longitudinal TSPO PET assessments for up to six months after the index stroke [27, 28]. Hence we conclude that the elevated [11C]PBR28 signal observed in this study is likely to result primarily from binding of TSPO rather than distribution effects.

The biological effects of the local microglial/macrophage and astrocyte recruitment after stroke [25, 26], which our data reflect, are complex and time-dependent. Different subsets of microglia fulfil multiple roles after ischaemic stroke [19]. In the early phase of experimental ischemic stroke, microglia produce pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β and reactive oxygen species resulting in further damage [6, 29] and secondary cell death in the penumbra region [30]. However, microglia also secrete anti-inflammatory factors after ischemic stroke [31, 32] which may promote neurogenesis and plasticity [6, 33]. In the context of an acute injury, appropriate astrocyte-microglia cross-talk is necessary for astrocytes to support neuronal survival and function [33]. An important finding of our study is that focal inflammation after stroke in patients is self-limiting in time and circumscribed in space. The localisation of the inflammatory response, within the borders of the infarct in the subacute phase, suggests that wide-spread activation of the resident cerebral immune cells is prevented by intrinsic mechanisms of inflammatory control [34]. Moreover, even within the infarct, our findings suggest that the accumulation of inflammatory cells resolves within 3 months after the event.

Our pilot study has limitations. The very stringent exclusion criteria resulted in a small sample size, therefore, our findings have to be confirmed in larger studies. Moreover, we did not collect arterial blood, but used SUV60-90 as the primary outcome measure. The SUV could subject to confounds with differences in peripheral TSPO binding (e.g., to lymphocytes) that would reduce the free radioligand concentration with significant systemic inflammation [35]. Previous studies have documented a strong regional overlap between [11C]PBR28 SUV60-90 and distribution volume [36, 37]. Finally, our 3 patients differed considerably in terms of age and in terms of vascular territory affected by the stroke.

Conclusions

TSPO PET imaging during the subacute phase suggests that the inflammatory response is confined to the infarcted area in stroke patients, which then resolves within three months. This also establishes a limited time window for administration of therapeutic anti-inflammatory agents, and could emphasise that locally delivered treatments could be effective. Further insights into the neuroinflammatory response after stroke are needed to guide the development of therapies targeting harmful and beneficial aspects of post-stroke inflammation.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials available upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TSPO:

-

18KD Translocator protein PET

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- SUV:

-

Standardised uptake values

- ROI:

-

Regions of interest

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- NIHSS:

-

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- mRS:

-

Modified Rankin Scale

- TAC:

-

Time-activity curves

- DWI:

-

Diffusion Weighted Images

References

Shichita T, Sakaguchi R, Suzuki M, et al. Post-Ischemic Inflammation in the Brain. Front Immunol. 3. Epub ahead of print 2012. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2012.00132.

Liesz A, Zhou W, Mracskó É, et al. Inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking shields the brain against deleterious neuroinflammation after stroke. Brain. 2011;134:704–20.

Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:391–7.

Iadecola C, Anrather J. The immunology of stroke: from mechanisms to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:796–808.

Xing C, Arai K, Lo EH, et al. Pathophysiologic Cascades in Ischemic Stroke. Int J Stroke. 2012;7:378–85.

Jayaraj RL, Azimullah S, Beiram R, et al. Neuroinflammation: friend and foe for ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:142.

Veltkamp R, Gill D. Clinical Trials of Immunomodulation in Ischemic Stroke. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13:791–800.

Alam MdM, Lee J, Lee S-Y. Recent progress in the development of TSPO PET ligands for Neuroinflammation Imaging in Neurological Diseases. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;51:283–96.

Chen W-H, Yeh H-L, Tsao C-W, et al. Plasma translocator protein levels and outcomes of acute ischemic stroke: a pilot study. Dis Markers. 2018;2018:1–7.

Schweitzer PJ, Fallon BA, Mann JJ, et al. PET tracers for the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor and uses thereof. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:933–42.

Trapani A, Palazzo C, de Candia M, et al. Targeting of the translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO): a valuable approach for nuclear and optical imaging of activated microglia. Bioconjug Chem. 2013;24:1415–28.

Luus C, Hanani R, Reynolds A, et al. The development of PET radioligands for imaging the translocator protein (18 kDa): What have we learned?. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2010;53(7):501–10.

Camsonne R, Crouzel C, Comar D, et al. Synthesis of N-(11C) methyl, N-(methyl-1 propyl), (chloro-2 phenyl)-1 isoquinoleine carboxamide-3 (PK 11195): a new ligand for peripheral benzodiazepine receptors. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 1984;21:985–91.

Gerhard A, Neumaier B, Elitok E, et al. In vivo imaging of activated microglia using [11 C]PK11195 and positron emission tomography in patients after ischemic stroke. NeuroReport. 2000;11:2957–60.

Gerhard A, Schwarz J, Myers R, et al. Evolution of microglial activation in patients after ischemic stroke: a [11C](R)-PK11195 PET study. Neuroimage. 2005;24:591–5.

Pappata S, Levasseur M, Gunn RN, et al. Thalamic microglial activation in ischemic stroke detected in vivo by PET and [11C]PK11195. Neurology. 2000;55:1052–4.

Price CJS, Wang D, Menon DK, et al. Intrinsic Activated Microglia Map to the Peri-infarct Zone in the Subacute Phase of Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:1749–53.

Radlinska BA, Ghinani SA, Lyon P, et al. Multimodal microglia imaging of fiber tracts in acute subcortical stroke. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:825–32.

Zinnhardt B, Wiesmann M, Honold L, et al. In vivo imaging biomarkers of neuroinflammation in the development and assessment of stroke therapies - towards clinical translation. Theranostics. 2018;8:2603–20.

Rorden C, Brett M. Stereotaxic display of brain lesions. Behav Neurol. 2000;12:191–200.

Grabner G, Janke AL, Budge MM, et al. Symmetric Atlasing and Model Based Segmentation: An Application to the Hippocampus in Older Adults. 2006. p. 58–66.

Gulyás B, Tóth M, Schain M, et al. Evolution of microglial activation in ischaemic core and peri-infarct regions after stroke: A PET study with the TSPO molecular imaging biomarker [C]vinpocetine. J Neurol Sci. 2012;320:110–7.

Imaizumi M, Kim H-J, Zoghbi SS, et al. PET imaging with [11C]PBR28 can localize and quantify upregulated peripheral benzodiazepine receptors associated with cerebral ischemia in rat. Neurosci Lett. 2007;411:200–5.

Kreisl WC, Mbeo G, Fujita M, et al. Stroke Incidentally Identified Using Improved Positron Emission Tomography for Microglial Activation. Arch Neurol. 66. Epub ahead of print 1 October 2009. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2009.208.

Owen DR, Narayan N, Wells L, et al. Pro-inflammatory activation of primary microglia and macrophages increases 18 kDa translocator protein expression in rodents but not humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:2679–90.

Nutma E, Stephenson JA, Gorter RP, et al. A quantitative neuropathological assessment of translocator protein expression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2019;142:3440–55.

Thiel A, Radlinska BA, Paquette C, et al. The temporal dynamics of poststroke neuroinflammation: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging-guided PET study with 11 C-PK11195 in acute subcortical stroke. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1404–12.

Thiel A, Heiss W-D. Imaging of Microglia Activation in Stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:507–12.

Sun M, Deng B, Zhao X, et al. Isoflurane preconditioning provides neuroprotection against stroke by regulating the expression of the TLR4 signalling pathway to alleviate microglial activation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11445.

Jeong H-K, Ji K, Min K, et al. Brain inflammation and microglia: facts and misconceptions. Exp Neurobiol. 2013;22:59–67.

Parada E, Egea J, Buendia I, et al. The Microglial α7-Acetylcholine Nicotinic Receptor Is a Key Element in Promoting Neuroprotection by Inducing Heme Oxygenase-1 via Nuclear Factor Erythroid-2-Related Factor 2. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1135–48.

Ponomarev ED, Veremeyko T, Weiner HL. MicroRNAs are universal regulators of differentiation, activation, and polarization of microglia and macrophages in normal and diseased CNS. Glia. 2013;61:91–103.

Matejuk A, Ransohoff RM. Crosstalk Between Astrocytes and Microglia: An Overview. Front Immunol. 11. Epub ahead of print 16 July 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01416.

Liesz A, Suri-Payer E, Veltkamp C, et al. Regulatory T cells are key cerebroprotective immunomodulators in acute experimental stroke. Nat Med. 2009;15:192–9.

Harberts E, Datta D, Chen S, et al. Translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) expression in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:51–7.

Albrecht DS, Forsberg A, Sandström A, et al. Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia – A multi-site positron emission tomography investigation. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;75:72–83.

Albrecht DS, Normandin MD, Shcherbinin S, et al. Pseudoreference Regions for Glial Imaging with 11 C-PBR28: Investigation in 2 Clinical Cohorts. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:107–14.

Acknowledgements

During the peer review process, Biogen had the opportunity to review the manuscript. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval on all content. We thank Imperial College Healthcare Trust National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Clinical Research Facility (CRF) for infrastructure support contributing to the study. PMM acknowledges generous personal support from the Edmond J Safra Foundation and Lily Safra and an NIHR Senior Investigator Award. His personal work is supported by the UK Dementia Research Institute, which receives its funding from UK DRI Ltd., funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Alzheimer’s Society and Alzheimer’s Research UK.

Funding

The “TSPO-PET in stroke” study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Biogen to Imperial College London (PI: Roland Veltkamp). RV, KH, EK are investigators of the Imperial BRC and partially funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 754517.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LD, RV analysed and interpreted the patient data. GS performed the data analysis, LD, RV, KH, PM writing up the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (London – Surrey Borders Research Ethics Committee 17/LO/1041). To be included, patients had to be able to understand the purpose and risks of the study and provide informed consent and authorisation to use protected health information in accordance with national and local subject privacy regulations and according to the local institutional review board’s (IRB’s)/ethics committee’s (EC’s) guidelines.

Consent for publication

Patients have signed a written informed consent for the publication.

Competing interests

Lucio D’Anna, Graham Searle, Kirsten Harvey report no disclosures. Roland Veltkamp has received fees for consulting and speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Pfizer, Daich Sankyo, Portola, Biogen, Medtronic, Morphosys, Amgen as well as research support from Bayer, Boehringer, BMS, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic outside of the present work. Paul M. Matthews has received consultancy fees from Roche, Adelphi Communications, Celgene, Neurodiem and Medscape. He has received honoraria or speakers’ fees from Novartis and Biogen and has received research or educational funds from Biogen, Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1.

Patient Clinical Summary including Age, Vascular Territory, NIHSS on admission, and Time points of combined MRI and PET scans. Supplemental Table 2. Regional Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) values in different brain regions at session 1 and session 2. Supplemental Table 3. Regional Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) values in different brain regions at session 2. Supplemental Table 4. Patient data including specific activity and mass of [11C]PBR28 administered and Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) time.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

D’Anna, L., Searle, G., Harvey, K. et al. Time course of neuroinflammation after human stroke – a pilot study using co-registered PET and MRI. BMC Neurol 23, 193 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-023-03178-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-023-03178-7