Abstract

Background

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has substantial physical, psychological, social and economic impacts, with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Considering its high incidence, the aim of this study was to identify epidemiological and clinical characteristics that predict mortality in patients hospitalized for TBI in intensive care units (ICUs).

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was carried out with patients over 18 years old with TBI admitted to an ICU of a Brazilian trauma referral hospital between January 2012 and August 2019. TBI was compared with other traumas in terms of clinical characteristics of ICU admission and outcome. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to estimate the odds ratio for mortality.

Results

Of the 4816 patients included, 1114 had TBI, with a predominance of males (85.1%). Compared with patients with other traumas, patients with TBI had a lower mean age (45.3 ± 19.1 versus 57.1 ± 24.1 years, p < 0.001), higher median APACHE II (19 versus 15, p < 0.001) and SOFA (6 versus 3, p < 0.001) scores, lower median Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score (10 versus 15, p < 0.001), higher median length of stay (7 days versus 4 days, p < 0.001) and higher mortality (27.6% versus 13.3%, p < 0.001). In the multivariate analysis, the predictors of mortality were older age (OR: 1.008 [1.002–1.015], p = 0.016), higher APACHE II score (OR: 1.180 [1.155–1.204], p < 0.001), lower GCS score for the first 24 h (OR: 0.730 [0.700–0.760], p < 0.001), greater number of brain injuries and presence of associated chest trauma (OR: 1.727 [1.192–2.501], p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Patients admitted to the ICU for TBI were younger and had worse prognostic scores, longer hospital stays and higher mortality than those admitted to the ICU for other traumas. The independent predictors of mortality were older age, high APACHE II score, low GCS score, number of brain injuries and association with chest trauma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among traumatic injuries, traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality among adults worldwide, leading often disabling to physical and psychological consequences [1,2,3]. According to data from the Global Burden of Disease [4], the overall incidence of TBI in 2016 was 369 per 100,000 inhabitants, with a 4% increase in the incidence rate between 1990 and 2016. In comparison, in Brazil, the incidence of TBI in 2016 was similar to the global incidence, with 383 per 100,000 inhabitants, with a percentage increase of 5.6 [4]. Furthermore, between 2008 and 2012, TBI accounted for 9,700 hospital deaths per year, overwhelming the public health system [5].

In addition to the high incidence, a European study revealed that almost half of hospitalized patients with TBI require admission to an intensive care unit duo to the risks of secondary brain injuries and complications [6]. These patients evolve to death on average in 15% of cases or require prolonged periods of hospitalization [7].

Detailed and contextualized epidemiological and clinical information on individuals with TBI admitted to the ICU are important for understanding the risks associated with morbidity and mortality. In addition, such information can contribute to the development of therapeutic and preventive measures that can be applied during hospitalization.

Despite the consequences of TBI on public health, in Brazil, there are still few studies detailing clinical and epidemiological characteristics that predict outcomes for these patients in the ICUs [1, 8,9,10]. Thus, the aim of this study was to identify epidemiological and clinical characteristics predictive of ICU mortality among patients admitted for TBI in a trauma referral hospital.

Materials and methods

This retrospective cohort study consecutively included patients with TBI over 18 years of age treated in the ICU between January 1, 2012, and August 31, 2019, in a trauma referral hospital in the city of Curitiba/PR, Brazil. The Complexo Hospitalar do Trabalhador is a level 1 trauma center according to the American Trauma Society classification, with a tertiary care facility available to the public health system and capable of providing comprehensive care for all aspects of injuries [11]. Patients are referred by the public health system center and the hospital follows the recommendations of the Brain Trauma Foundation [12]. All patients with an altered Glasgow Coma Scale or any acute abnormality on CT and who had an indication of full support at hospital admission were admitted to the ICU.

Patients who were hospitalized for late sequelae of TBI and those for whom there ware no data on age, sex, and type of TBI on the CT or ICU outcome recorded in the electronic medical record and in the daily medical follow-up sheets at the bedside were excluded.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Instituto de Neurologia de Curitiba under protocol number 5.663.561 (Project title: Factors associated with mortality and hospital time in patients with traumatic brain (TBI) in intensive care units (ICU) in a trauma reference hospital in the city of Curitiba/PR, Brazil between 2012 and 2019; CAAE:61409122.9.0000.5227) and the need for informed consent was waived given the noninterventional study design and data collection was performed only in clinical records, without contact with the participants. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde - CNS). The STROBE guidelines were used to ensure the reporting of this study.

Using electronic medical records and daily bedside medical tracking forms, data were collected on the sex and age of the patient and on the mechanism of trauma (e.g., gunshot wound (GSW); stab wound (SW); physical aggression; being run over; bicycle accident; collisions; motorcycle accident; and falling from the same level (SLF) and/or falling from a height (OLF). In addition, information was collected on the presence of polytrauma and/or skull trauma, and injuries identified on cranial CT were recorded as follows: subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), subdural haematoma (SDH), epidural haematoma (EDH), diffuse axonal injury (DAI), intraparenchymal haemorrhage (IPH), cerebral contusion, skull depression, skull fracture, intraventricular haemorrhage, ischaemia, cerebral oedema and/or pneumocephalus.

Data were also collected on the type and number of TBI-associated injuries, which may present as injuries to chest, abdomen, pelvis, spine, limbs and/or face and neck. The types of interventions ware recorded: conservative treatment, intracranial pressure monitoring (ICPm), craniectomy, hematoma drainage, external ventricular shunt(EVD) and correction of depression and/or fracture correction. Last, the following data for ICU admission were collected: SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment) score, APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) score and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores and outcome (length of hospitalization, discharge or death, reason for death and GCS score at discharge).

Statistical analysis

The results for categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies, and the results for quantitative variables are presented as the mean and standard deviation, median and minimum and maximum values.

For quantitative variables, comparisons between 2 groups were performed using Student’s t test or the nonparametric Mann‒Whitney test for data with a nonnormal distribution. The association between 2 categorical variables was performed using the chi-square test, and when both were dichotomous, Fisher’s exact test was applied.

Simple and multiple binary logistic regression models of the following factors alone and/or adjusted were used to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for mortality: age, trauma mechanisms, APACHE II score, GCS score, SOFA score in the first 24 h, associated injuries, number of injuries on cranial CT and presence of each brain injury on CT, compared with the absence of any injury. The significance of each of the variables in the models was evaluated using the Wald test.

The level of statistical significance was set at 5%, and the data were analysed using the statistical analysis software IBM SPSS, version 28.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Imputation of missing data was not performed.

Results

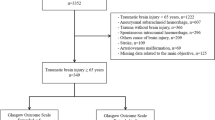

Between January 2012 and August 2019, 5,072 trauma victims were admitted to the ICU. Of these, 4816 patients older than 18 years at the time of ICU admission were screened for TBI, of which 23.5% were diagnosed with a TBI (n = 1132). We excluded 17 patients hospitalized for late sequelae of TBI and 1 who was transferred to the ICU of another hospital, making it impossible to determine the outcome. Thus, 1,114 patients made up the cohort of this study (Fig. 1).

Comparing the profile of the 1,114 individuals with TBI with that of the 3,684 individuals with other traumas (Table 1) indicated that those admitted to the ICU for TBI were significantly younger and had worse prognostic scores on admission (APACHE II, SOFA and GCS scores); they remained hospitalized longer, and there was a higher proportion of deaths in this group.

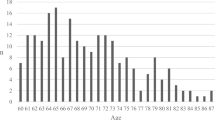

The 1114 individuals with TBI accounted for 23.2% of trauma patients admitted to the ICU from 2012 to August 2019. The annual incidence of ICU admission by TBI ranged from 32.9 to 17.9%, with the lowest incidence recorded in 2017 (Fig. 2A). The overall mortality rate for the individuals with TBI was 27.6%, with no significant difference between the rates in the years evaluated (Fig. 2B).

Of the 1,114 patients admitted to the ICU due to TBI, 27.6% died. Among them, the mean age was 47.6 ± 19.7 years, higher than those who progressed to discharge. Among those with TBI, there was a predominance of males, with no difference in the proportion of deaths between the sexes (Table 2).

The most common trauma mechanisms were falls from the same level followed by motorcycle accidents, corresponding to 39.6% of all TBIs. However, the TBI mechanism with the highest mortality rate was GSW/SW, followed by bicycle accidents and being run over. There was a significant difference in the proportion of deaths between the trauma mechanisms (Table 2).

More than 60% of patients had only one injury on cranial CT, and the increase in the number of associated injuries was directly related to mortality. The most frequent injuries evidenced on tomography were SDH and SAH. Patients with ischaemia, cerebral oedema and intraventricular haemorrhage had the highest mortality rates. In addition, compared toother injuries, a significantly higher proportion of patients with brain contusions, skull fractures, SAH, SDH, IPH, intraventricular haemorrhage, cerebral oedema and ischaemia died (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

The majority, 46.6%, were characterized as severe TBI (GCS 3 to 8), 18.4% as moderate (GCS 9 to 12) and 35% as mild (GCS 13 to 15). The presence of severe TBI was significantly associated with mortality. Furthermore, patients who died had significantly lower GCS scores and higher APACHE II and SOFA scores in the first 24 h in ICU. The presence of trauma in other areas, except chest trauma was not significantly related to death. (Table 2).

Most TBIs were treated surgically, with no difference in the mortality rate between surgical and conservative treatment. Among the surgical procedures, the most frequent was ICPm, and the approach associated with higher mortality was decompressive craniectomy. The median length of stay in the ICU was 7 days, which was significantly longer among those who died. At the time of ICU outcome, the majority (74.1%) of the patients were classified as life-sustaining treatments (LST) level A i.e., all necessary, possible, and available LST measures to save life and restore health, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation if cardiopulmonary arrest. (Table 2).

Of the 807 survivors, 781 (96.8%) had the Glasgow Coma Scale recorded at ICU discharge. The mean score was 13.2, and the median was 14, ranging from 3 to 15. Among the 307 patients who died, the direct cause of death was noted in the discharge summary of 262 (85.3%) patients. Brain death was the most frequent, accounting for 42.7% of deaths, followed by infection (40.8%), hemorrhagic shock (4.6%), unidentified cause (3.4%), pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) (1.9%), sepsis plus acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (1.5%), ARDS alone (1.1%), acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (1.1%), cardiac arrest (CA) duo toventricular fibrillation (VF) (1.1%), and others (1.5%).

Variables that were significantly different between discharge and death were analysed as prognostic factors for mortality using univariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3). Older age, higher APACHE II and SOFA scores and lower GCS scores at admission were associated with higher mortality. Regarding TBI mechanisms, less lethal trauma (physical aggression), GSW/SW, being run over and bicycle accidents were associated with a higher risk of mortality (Table 3).

The greater the number of injuries on cranial CT, the greater the risk of mortality when compared with the absence of brain lesion; patients with 3 injuries on cranial CT were 10 times more likely to die. The presentation of ischaemia, intraventricular haemorrhage, cerebral oedema, cerebral contusions, skull fractures, SAH, SDH and/or IPH increased the odds of death of patients with TBI. Cerebral ischaemia and oedema increased the odds by 29 and 21 times, respectively (Table 3). Polytrauma was not associated with a worse outcome; however, the presence of associated chest injury increased the odds of death (Table 3).

Finally, older age, a higher APACHE II score, a lower GCS score in the first 24 h, a greater number of brain injuries identified on CT, and the presence of associated chest trauma remained risk factors for mortality in patients with TBI after adjusting for each in a multiple regression model (Table 4).

Discussion

Compared with other severe traumas, TBI is the most prevalent and, among traumas, has the highest morbidity and mortality [13, 14]. In trauma, injuries to the central nervous system are the main causes of death, followed by hemorrhagic shock and sepsis [14,15,16]. Individuals with TBI are younger and mostly men [17,18,19] and have worse prognostic score values at admission and longer ICU stays. As observed in Europe, patients with neurological injuries admitted to the ICU had higher SOFA scores, lower GCS scores on admission, longer ICU stays and higher mortality rates [20].

In this study, the mortality rate for patients with TBI was 27.6%. Older age, a higher APACHE II score, a lower Glasgow score in the first 24 h, a higher number of brain injuries identified on CT, and the presence of associated chest trauma were independent predictors of mortality.

The findings corroborate previous studies that identified older age and lower GCS scores as predictors of mortality in patients with severe TBI [7, 17, 21,22,23,24,25]. A population based study conducted in Rwanda, Africa, showed that age over 50 years and GCS score lower than 13 were significantly associated with death [23]. In previous studies, younger patients had higher GCS scores at ICU admission and discharge [26], and mortality increased with increasing age [14, 27]. One explanation for the increased mortality in patients with advanced age is the increased use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs, leading to greater bleeding complications in patients with severe trauma [13].

Falls from the same level and traffic accidents were the main trauma mechanisms identified, similar to those reported in European studies [18, 28]. Falls from the same level are more common in the elderly population, while traffic accidents are more common in the young population [17, 18, 29]. The higher incidence of falls in the elderly population can be explained by their increased in life expectancy accompanied by the increase in comorbidities [13]. For TBIs caused by traffic accidents, the most common mechanism among our cohort was motorcycle accidents, a finding that is different from observations in Europe, where bicycle accidents were more frequent [28,29,30].

Subdural and subarachnoid haemorrhages were the most frequent findings on CT of the head of patients with TBI, a finding consistent with the results of a European study [6]. The increase in the occurrence of intracranial haemorrhages is associated with olderage and a decrease in GCS score [31]. The presence of SAH due to trauma is often accompanied by other intracranial haemorrhages [32]. When SAH is concomitant with 2 other intracranial haemorrhage, there is a 9-fold increase in mortality, and when associated with SDH, there is a 16-fold increase in the chance of death [25, 32]. Thus, a greater number of brain injuries, especially haemorrhagic ones, is associated with a greater chance of death.

The association of thoracic trauma with TBI significantly increased the mortality of patient in our study. These findings are corroborated by other studies, also demonstrating higher mortality among patients with pulmonary contusions [33], and that the presence of TBI and concomitant chest trauma significantly increased mortality and prolonged ICU stay and duration of mechanical ventilation [34].

Higher APACHE II scores are a risk factor for mortality in patients admitted to ICUs [35, 36]. In the present study, individuals with TBI admitted to the ICU had a mean APACHE score of 20 points, and among the patients who died, the mean score was 29 points. These data are very similar to those reported in a study conducted in Turkey [37], in which the mean APACHE II score was 30 points for patients with TBI who died. This scale has shown good performance in terms of discrimination, calibration, accuracy and satisfactory results in the prediction of ICU mortality in patients with TBI [35, 38].

In the univariate analysis, the SOFA score was significantly related to mortality, with higher scores for patients who died [38]. Zygun D et al. [39] demonstrated that the increased mortality of patients with TBI is related to higher scores on the cardiovascular component of the SOFA.

Regarding therapeutic management, no differences were observed in mortality between conservative or surgical intervention. However, in 2020, Gao et al. [21] showed that decompressive craniotomy and craniectomy reduced mortality in patients with severe TBI and no pupillary light reflex.

At the time of ICU outcome, the majority (74.1%) of the patients were classified as life-sustaining treatments (LST) level A. In our institutional protocol, in view of the brain trauma foundation protocols and focus on rehabilitation, it is recommended to wait 6 months for support limitation. These data are in agreement with the results of other authors who suggest caution in considering the withdrawal of care in patients with TBI duo to the delay in the recovery of the level of consciousness [40].

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, not all data were available, such as: Injury Severity Score (ISS), regional AIS (Abbreviated injury score), Marshal Score, morbidity, incidence of ARDS and pneumonia. Since data were collected exclusively from electronic medical records, information on prehospital care, pupil assessment, functional outcome, and haemostasis disorders was not available. Data collection was performed only at the time of hospitalization, it was not possible to control confounding factors regarding the evolution of each patient during hospitalization. However, the findings of our study, derived from the analysis of a large TBI patients in a trauma referral hospital, allow a broad understanding of the epidemiological profile of TBI patients.

In conclusion, individuals with TBI have higher chances of mortality and longer hospital stay, are younger, have higher APACHE II and SOFA scores and have lower GCS scores on ICU admission. Significantly associated predictors of ICU mortality include older age, higher APACHE II score, lower GCS score in the first 24 h, higher number of brain injuries, and concomitant chest trauma. TBI results in extensive consequences for patients’ quality of life and represents a substantial burden on health services. Therefore, understanding the risk factors and predictors of mortality is necessary for the development of more effective preventive and therapeutic measures and for better planning of the management of patients with TBI, in order to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Zenodo repository, DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7054506 and hyperlink to dataset is https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7054506.

Abbreviations

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

- ICUs:

-

Intensive care units

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- SOFA:

-

Sequential organ failure assessment

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GSW:

-

Gunshot wound

- SW:

-

Stab wound

- SAH:

-

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

- SDH:

-

Subdural haematoma

- EDH:

-

Epidural haematoma

- DAI:

-

Diffuse axonal injury

- IPH:

-

Intraparenchymal haemorrhage

- ICPm:

-

Intra cranial pressure monitoring

- EVD:

-

External ventricular derivation

- PTE:

-

Pulmonary thromboembolism

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- CA:

-

Cardiac arrest

- VF:

-

Ventricular fibrillation

- SLF:

-

Same-level fall

- OLF:

-

Fall from other level

- SCI:

-

Spinal cord injure

References

Gaudêncio TG, Leão G. De M. A Epidemiologia do Traumatismo Crânio- Encefálico. Rev Neurociências. 2013;21(3):427–34.

de Oliveira CO, Ikuta N, Regner A. Biomarcadores prognósticos no traumatismo crânio-encefálico grave. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2008;20(4):411–21.

Bruns J, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia. 2003;44(s10):2–10.

Feigin VL, Nichols E, Alam T, Bannick MS, Beghi E, Blake N, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459–80.

De Almeida CER, De Sousa Filho JL, Dourado JC, Gontijo PAM, Dellaretti MA, Costa BS. Traumatic brain Injury Epidemiology in Brazil. World Neurosurg. 2016;87:540–7.

Steyerberg EW, Wiegers E, Sewalt C, Buki A, Citerio G, De Keyser V, et al. Case-mix, care pathways, and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury in CENTER-TBI: a european prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(10):923–34.

Chelly H, Bahloul M, Ammar R, Dhouib A, Mahfoudh K, Ben, Boudawara MZ, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of traumatic head injury following road traffic accidents admitted in ICU “analysis of 694 cases. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2017;45(2):245–53.

Magalhães ALG, de Souza LC, Faleiro RM, Teixeira AL. Miranda AS de. EPIDEMIOLOGIA DO TRAUMATISMO CRANIOENCEFÁLICO NO BRASIL.Rev Bras Neurol. 2017;53(2).

Xenofonte MR, Penha C, Marques C. Perfil epidemiológico do traumatismo cranioencefálico no Nordeste do Brasil. Rev Bras Neurol. 2021;57(1):17–21.

Pogorzelski GF, Silva TAAL, Piazza T, Lacerda TM, Netto FACS, Jorge AC, et al. Epidemiology, prognostic factors, and outcome of trauma patients admitted in a brazilian intensive care unit. Open Access Emerg Med. 2018;10:81.

Southern AP, Celik DH, EMS, Trauma CD. [Updated 2022 Jul 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560553/

Carney N, Totten AM, O’Reilly C, Ullman JS, Hawryluk GWJ, Bell MJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(1):6–15.

Alberdi F, García I, Atutxa L, Zabarte M. Epidemiología del trauma grave. Med Intensiva. 2014;38(9):580–8.

Dutton RP, Stansbury LG, Leone S, Kramer E, Hess JR, Scalea TM. Trauma mortality in mature trauma systems: are we doing better? An analysis of trauma mortality patterns, 1997–2008. J Trauma - Inj Infect Crit Care. 2010;69(3):620–6.

Søreide K, Krüger AJ, Vårdal AL, Ellingsen CL, Søreide E, Lossius HM. Epidemiology and contemporary patterns of trauma deaths: changing place, similar pace, older face. World J Surg. 2007;31(11):2092–103.

Trajano AD, Pereira BM, Fraga GP. Epidemiology of in-hospital trauma deaths in a brazilian university hospital. BMC Emerg Med. 2014;14(1):1–9.

Perel PA, Olldashi F, Muzha I, Filipi N, Lede R, Copertari P, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2008;336(7641):425–9.

Peeters W, van den Brande R, Polinder S, Brazinova A, Steyerberg EW, Lingsma HF, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in Europe. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015;157(10):1683–96.

Capizzi A, Woo J, Verduzco-Gutierrez M. Traumatic Brain Injury: an overview of Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Medical Management. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(2):213–38.

Mascia L, Sakr Y, Pasero D, Payen D, Reinhart K, Vincent JL. Extracranial complications in patients with acute brain injury: a post-hoc analysis of the SOAP study. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(4):720–7.

Gao G, Wu X, Feng J, Hui J, Mao Q, Lecky F, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury in China: a prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):670–7.

Kokkinou M, Kyprianou TC, Kyriakides E, Constantinidou F. A population study on the epidemiology and outcome of brain injuries in intensive care. NeuroRehabilitation. 2020;47(2):143–52.

Krebs E, Gerardo CJ, Park LP, Nickenig Vissoci JR, Byiringiro JC, Byiringiro F, et al. Mortality-Associated characteristics of patients with traumatic Brain Injury at the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali, Rwanda. World Neurosurg. 2017;102:571–82.

Hemphill JC, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32(4):891–6.

Wu E, Marthi S, Asaad WF. Predictors of mortality in traumatic intracranial hemorrhage: a National Trauma Data Bank Study. Front Neurol. 2020;11:587587.

Leitgeb J, Mauritz W, Brazinova A, Majdan M, Janciak I, Wilbacher I, et al. Glasgow Coma Scale score at intensive care unit discharge predicts the 1-year outcome of patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2013;39(3):285–92.

Hukkelhoven CWPM, Steyerberg EW, Rampen AJJ, Farace E, Habbema JDF, Marshall LF, et al. Patient age and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury: an analysis of 5600 patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(4):666–73.

Schwenkreis P, Gonschorek A, Berg F, Meier U, Rogge W, Schmehl I et al. Prospective observational cohort study on epidemiology, treatment and outcome of patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in German BG hospitals.BMJ Open. 2021;11(6).

Lawrence T, Helmy A, Bouamra O, Woodford M, Lecky F, Hutchinson PJ. Traumatic brain injury in England and Wales: prospective audit of epidemiology, complications and standardised mortality. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012197.

Walder B, Haller G, Rebetez MML, Delhumeau C, Bottequin E, Schoettker P, et al. Severe traumatic brain Injury in a high-income country: an epidemiological study. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(23):1934–42.

Styrke J, Stålnacke BM, Sojka P, Björnstig U. Traumatic Brain Injuries in a Well-Defined Population: Epidemiological Aspects and Severity. 2007;24(9):1425–36. https://home.liebertpub.com/neu

Rau CS, Wu SC, Hsu SY, Liu HT, Huang CY, Hsieh TM, et al. Concurrent types of Intracranial Hemorrhage are Associated with a higher mortality rate in adult patients with traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage: a cross-sectional retrospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):47–87.

Balci AE, Balci TA, Eren Ş, Ülkü R, Çakir O, Eren N. Unilateral post-traumatic pulmonary contusion: findings of a review. Surg Today. 2005;35(3):205–10.

Schieren M, Wappler F, Wafaisade A, Lefering R, Sakka SG, Kaufmann J et al. Impact of blunt chest trauma on outcome after traumatic brain injury- a matched-pair analysis of the TraumaRegister DGU®.Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28(1).

Rowe M, Brown J, Marsh A, Thompson J. Predicting Mortality Following Traumatic Brain Injury or Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: An Analysis of the Validity of Standardized Mortality Ratios Obtained From the APACHE II and ICNARCH-2018 Models.J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2022

Anderson D, Kutsogiannis DJ, Sligl WI. Sepsis in traumatic Brain Injury: Epidemiology and Outcomes. Can J Neurol Sci. 2020;47(2):197–201.

Gürsoy G, Gürsoy C, Kuşcu Y, Demirbilek SG. APACHE II or INCNS to predict mortality in traumatic brain injury: a retrospective cohort study. Ulus Travma ve Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2020;26(6):893–8.

Dübendorfer C, Billeter AT, Seifert B, Keel M, Turina M. Serial lactate and admission SOFA scores in trauma: an analysis of predictive value in 724 patients with and without traumatic brain injury. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2013;39(1):25–34.

Zygun D, Berthiaume L, Laupland K, Kortbeek J, Doig C. SOFA is superior to MOD score for the determination of non-neurologic organ dysfunction in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2006;10(4):1–10.

Kowalski RG, Hammond FM, Weintraub AH, Nakase-Richardson R, Zafonte RD, Whyte J, et al. Recovery of consciousness and functional outcome in moderate and severe traumatic brain Injury. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(5):548–57.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participating centers and Verônica Barros for the support, interventions in our study and all the collaboration.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ARN, EDSJ and GH; data curation, RSB and ARN; formal analysis, RSB, MMJ; investigation, VBS and MBC; methodology, ARN, EDSJ, GH, RSB, ACKN and MCO; project administration, ARN; supervision, ARN and MCO; visualization, ARN, HAGT, EDSJ, GH, VBS, RSB, ACKN, FBR, MBC and MCO; writing—original draft preparation, EDSJ, GH, RSB, ACKN, MCO; writing—review and editing, ARN, HAGT, EDSJ, GH, VBS, RSB, ACKN, MMJ, FBR, MBC and MCO.

All authors have approved the submitted version and agreed to be personally accountable its own contributions and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Instituto de Neurologia de Curitiba under protocol number 5.663.561 on September 17, 2018, and the need for informed consent was waived given the noninterventional study design and data collection was performed only in clinical records, without contact with the participants. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde - CNS). The STROBE guidelines were used to ensure the reporting of this study.

The ethics committee of the Instituto de Neurologia de Curitiba approved the waiver of informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Réa-Neto, Á., da Silva Júnior, E.D., Hassler, G. et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics predictive of ICU mortality of patients with traumatic brain injury treated at a trauma referral hospital – a cohort study. BMC Neurol 23, 101 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-023-03145-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-023-03145-2