Abstract

Background

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE) is a rare encephalopathy characterized by multiple symmetrical brain lesions, mainly involving thalami. Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a rare systemic inflammatory condition of unknown cause characterized by fever, sore throat, rash and joint pain. Both entities are considered to be triggered by infections and associated with hypercytokinemia.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old male was diagnosed with AOSD at local hospital because of 3-week-long high fever, sore throat, arthralgia, transient skin rash, lymphadenopathy, leukocytosis, hyperferritinemia, and absence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor (RF). Corticosteroids were not used because of delayed diagnosis. Three weeks after the onset, the patient suddenly fell unconscious and was transferred to our hospital. Brain CT and MRI revealed symmetrical lesions involving thalami, striatum and brain stem, consistent with ANE. One day after admission, his condition aggravated and brain CT revealed hemorrhage in the lesions. He died 3 days after admission.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of ANE preceded by AOSD. The underlying mechanism is still unclear. Early recognizing of the two conditions is difficult but prognostically important.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE) is a rare type of encephalopathy characterized by symmetrical brain lesions involving thalami, putamina, cerebral and cerebellar white matter, and brain stem tegmentum [1]. Though the pathogenesis of ANE is unclear, it is generally considered to be a parainfectious encepalopathy [1] and “cytokine storm” may play a role in the development of ANE [2]. Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a rare systemic inflammatory condition of unknown etiology characterized by high fever, transient skin rash, arthralgia/arthritis, sore throat, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, leukocytosis, abnormal liver function tests, hyperferritinemia and absence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) [3]. AOSD is also associated with infections and hypercytokinemia [4]. Here, we report a case of ANE accompanied with AOSD. To the best of knowledge, this is the first case of AOSD complicated with ANE in the literature.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old male developed fever of 37.8℃, sore throat, and pain and swelling in elbows, wrists, knees and ankles 3 weeks before admission. Physical examination found grade 1 tonsils and laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis of 15.79 × 10^9/L (85.5% neutrophils) at the onset. He was treated for acute pharyngitis with cephalosporin and penicillin for 11 days but symptoms did not resolve. He was admitted to the local hospital 10 days ago because of fever of up to 40.1℃, accompanied with skin rash which was more conspicuous during febrile episodes. Blood tests showed elevated inflammatory markers but did not find clues of infections or autoimmune diseases (Table 1). Tumor markers, vitamins levels and thyroid function were normal. Bone marrow aspiration showed no findings of phagocytosis. CT scans of the thorax and abdomen were unremarkable. During admission, he was treated on an empirical basis with piperacillin/tazobactam, moxifloxacin, imipenem/cilastatin, teicoplanin, tigecycline and meropenem sequentially but were all of no avail. AOSD was thus suspected. However, he suddenly fell unconscious 14 h ago and was transferred to our hospital. Glucosteroids was not used as planned because of delayed diagnosis of AOSD.

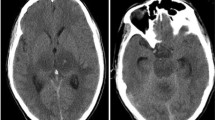

On admission, vital signs were as follows: T: 38℃, HR: 87 bpm, R: 18 bpm, BP:117/86 mmHg, SPO2: 98%. Physical examination found patchy salmon-colored skin rash in the trunk and thighs (Fig. 1A). Enlarged axillary lymphadenopathy was detected but with no hepatosplenomegaly. Glasgow coma scale was graded 4 (E1V1M2). Pupils were symmetric in size but unreactive to light. Neck was stiff. Babinski signs were positive bilaterally. Laboratory tests results were listed in Table 1. Lumbar puncture revealed opening pressure of 130mmH2O. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed elevated erythrocyte count to 120 × 10^6/L with normal leukocyte count. CSF glucose, protein and chloride levels were normal. Cultures, cytology and next generation sequencing (NGS) of CSF were negative. Brain CT and MRI revealed lesions involving bilateral striatum, thalamus, and brain stem, typical for ANE (Fig. 1B-F). Brain digital subtracted angiography (DSA) was conducted to rule out venous thrombosis and other cerebral vascular diseases. His condition deteriorated rapidly and was intubated on hospital day 2. A repeat brain CT revealed hemorrhage in the lesions (Fig. 1G). ANE accompanied with AOSD was considered. However, his relatives gave up treatment and the patient passed away on hospital day 3.

Picture of the patient (A) showing salmon-colored rash in the trunk (black arrows). On hospital day (HD) 1, brain CT (B), T1 weighted (C), and T2-FLAIR (D, E) MRI demonstrating symmetric lesions involving thalami, striatum and brain stem, consistent with acute necrotizing encephalopathy (white arrows). Diffusion weighted images (F) showing typical “concentric/laminar structure”. Brain CT on HD 2 revealing hemorrhage in the lesions (G, white arrows)

Discussion and conclusion

ANE is a rare form of encephalopathy which was first reported by Mizuguchi et al. in 1995 [1]. It is more commonly seen in children than in adults without racial predilection. Most cases of ANE are sporadic but familial ANE which is caused by the missense mutations in the RANBP2 gene has been reported [5]. Infection is a common trigger for ANE. Viral prodrome usually precedes neurological deficits, but pathologically, the lesions show edema, hemorrhage, necrosis with few inflammatory cells, suggesting blood–brain barrier breakdown rather than direct viral invasion or parainfectious demyelination. Because clinical manifestations lack specificity, the diagnosis of ANE is mainly based on characteristic neuroradiologic findings, that is, multifocal and symmetric brain lesions, mainly involving bilateral thalami. The pathogenesis of ANE has not been fully elucidated. The most prevalent hypothesis is “cytokine storm”, involving interleukin- (IL-) 6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-10, IL-15, IL-1β, and soluble TNF receptor [2]. IL-6 was neurotoxic at high concentrations and TNF-α could damage the endothelium of the central nervous system [2]. The differentials include Leigh syndrome, thrombosis of the internal cerebral veins or straight sinus, Wernicke encephalopathy and Japanese encephalitis. In the present case, vitamins, glucose, lactate and ammonia levels were all normal. Cerebral veins thrombosis was ruled out by DSA. Infections were excluded by many laboratory methods and unsuccessful empirical antibiotics treatment. Treatment of ANE is mainly supportive. Intravenous glucocorticoids, immunoglobulin, and plasmapheresis were tried in previous cases but prognosis is still very poor [2]. Steroid within 24 h after the onset was related to better outcome in children with ANE without brainstem lesions [6], so steroid treatment should be initiated as early as possible.

AOSD is an uncommon systemic auto-inflammatory disease. In our case, the presentations and laboratory findings supported the diagnosis of AOSD according to criteria proposed by Yamaguchi et al. [3]. Similar to ANE, AOSD may also be triggered by viral or bacterial infection and pathogenesis also involves “cytokine storm”. Relevant proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-18 [7] largely overlap with those found in ANE [2]. Despite the theorical possibility of concurrence of ANE and AOSD, similar literature is few. Zhao M, et al.reported neurological complications occurred in 7.5% patients with AOSD and aseptic meningitis was the most common presentation [8]. It is believed that in the hyperinflammatory state, activated neutrophils in peripheral blood can cross the blood–brain barrier and induce meningitis [8]. Cerebral infarction [8], cerebral hemorrhage [9], encephalitis [8], demyelinating encephalopathy [10], and reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome [11] were anecdotally reported. Up to our knowledge, this is the first case report of coexistence of AOSD and ANE. We assume the rarity in clinical practice may be due to the diagnostic challenges in both conditions. The diagnosis of AOSD is highly dependent on the physician's judgment and is generally an exclusive one. The median interval between onset of symptoms and a definite diagnosis of AOSD ranged between 1 and 4.1 months [12]. As for ANE, it typically develops in children younger than 5 years of age; very few case reports have been published in adults [13], so it is an under-recognized syndrome. Delayed diagnosis of AOSD in our case hampered timely immunotherapy and cytokine storm became so severe that ANE followed.

There were two limitations in this case report. AOSD is an exclusive diagnosis that needs to exclude infections, tumors, and rheumatic diseases. In the present case, laboratory studies and failure of empirical biotics treatment did not support infections or other rheumatic diseases, but underlying tumors were difficult to be ruled out. Lymphoma [14], leukemia [15], breast cancer [16], ovarian cancer [17], and thyroid cancer [18] can give rise to AOSD-like symptoms. Although bone marrow aspiration and CT scans of thorax and abdomen were performed in this case, a total-body PET-CT scan was indicated. The other pitfall is macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) could not be completely excluded in this case. MAS is a severe inflammatory systemic abnormality with lethal potential characterized by pancytopenia, coagulopathy, hepatopathy, neurological disorders and hemophagocytosis [19]. It develops in 10.2% patients with AOSD and has an association with an increasing risk of neurological manifestations [8]. ANE has been reported in cases with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) [20, 21]. Although our patient had no fulfilment of criteria for the diagnosis of HLH [22] due to the absense of splenomegaly, cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hemophagocytosis initially, HLH was still possible in the late stage and a repeat bone marrow aspiration was necessary. However, the illness progressed so rapidly that scheduled PET-CT and bone marrow aspiration were not able to be performed.

In conclusion, we report a case of ANE associated with AOSD. Physicians should be aware of this uncommon but life-threatening complication when patients with AOSD developed conscious disturbance. More observations are warranted and the underlying mechanism needs to be elucidated.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ANE:

-

Acute necrotizing encephalitis

- AOSD:

-

Adult-onset Still’s disease

- ANA:

-

Antinuclear antibodies

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- DSA:

-

Digital subtracted angiography

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- MAS:

-

Macrophage activation syndrome

- HLH:

-

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

References

Mizuguchi M, Abe J, Mikkaichi K, et al. Acute necrotising encephalopathy of childhood: a new syndrome presenting with multifocal, symmetric brain lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:555–61.

Wu X, Wu W, Pan W, Wu L, Liu K, Zhang HL. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy: an underrecognized clinicoradiologic disorder. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:792578.

Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424–30.

Mavragani CP, Spyridakis EG, Koutsilieris M. Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: From Pathophysiology to Targeted Therapies. Int J Inflam. 2012;2012:879020.

Neilson DE, Adams MD, Orr CM, et al. Infection-triggered familial or recurrent cases of acute necrotizing encephalopathy caused by mutations in a component of the nuclear pore, RANBP2. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:44–51.

Okumura A, Mizuguchi M, Kidokoro H, et al. Outcome of acute necrotizing encephalopathy in relation to treatment with corticosteroids and gammaglobulin. Brain Dev. 2009;31:221–7.

Kadavath S, Efthimiou P. Adult-onset Still’s disease-pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and new treatment options. Ann Med. 2015;47:6–14.

Zhao M, Wu D, Shen M. Adult-onset Still’s disease with neurological involvement: a single-centre report. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:4152–7.

Kurabayashi H, Kubota K, Tamura K, Shirakura T. Cerebral haemorrhage complicating adult-onset Still’s disease: a case report. J Int Med Res. 1996;24:492–4.

Jie W, Miao L, Yankun S, Hong Y, Zhongxin X. Demyelinating encephalopathy in adult onset Still’s disease: case report and review of the literatures. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:2213–6.

Khobragade AK, Chogle AR, Ram RP, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome in a case of adult onset Still’s disease with concurrent thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: response to high dose immunoglobulin infusions. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:59–62.

Efthimiou P, Kontzias A, Hur P, Rodha K, Ramakrishna GS, Nakasato P. Adult-onset Still’s disease in focus: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and unmet needs in the era of targeted therapies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51:858–74.

Kidokoro H. Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy: A Disease Meriting Greater Recognition. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:2255–6.

Dudziec E, Pawlak-Bus K, Leszczynski P. Adult-onset Still’s disease as a mask of Hodgkin lymphoma. Reumatologia. 2015;53:106–10.

Sugawara T, Tsukada T, Wakita Y, et al. A case of myelodysplastic syndrome progressing to acute myelocytic leukemia in which adult-onset Still’s disease had occurred 6 years before. Int J Hematol. 1993;59:53–7.

Fukuoka K, Miyamoto A, Ozawa Y, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease-like manifestation accompanied by the cancer recurrence after long-term resting state. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:704–7.

Schade L, Fritsch S, Gentili AC, de Noronha L, Azevedo VF, Paiva ES. Adult Still’s disease associated with ovarian cancer: case report. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2013;53:532–4.

Tirri R, Capocotta D. Incidental papillary thyroid cancer diagnosis in patient with adult-onset Still’s disease-like manifestations. Reumatismo. 2019;71:42–5.

Bojan A, Parvu A, Zsoldos IA, Torok T, Farcas AD. Macrophage activation syndrome: A diagnostic challenge (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:904.

Radmanesh F, Rodriguez-Pla A, Pincus MD, Burns JD. Severe cerebral involvement in adult-onset hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;76:236–7.

Akiyoshi K, Hamada Y, Yamada H, Kojo M, Izumi T. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy associated with hemophagocytic syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;34:315–8.

Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–31.

Acknowledgements

Dr Abhijeet Kumar Bhekharee kindly help us with language modification.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871277). The funding covered the fee of next generation sequencing of CSF, the fee of inviting a radiologist to interpret the data, and the fee of publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y.: initial manuscript preparing; M.L.W.: patient managing, initial manuscript preparing; S.G.C: image editing, literature review; Y.Z.: reviewing and revising manuscript, final approval of the manuscript to be submitted. M.L.W., X.Y., and S.G.C. contribute equally to the work. All authors have read and approved the manuscript of “Adult-onset Still’s disease with concurrent acute necrotizing encephalopathy: a case report”.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is approved by ethics committee of Donglei brain hospital.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Wei, M., Chu, S. et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease with concurrent acute necrotizing encephalopathy: a case report. BMC Neurol 22, 329 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02844-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02844-6