Abstract

Background

Care for People with Multiple Sclerosis (PwMS) is increasingly complex, requiring innovations in care. Canada has high rates of MS; it is challenging for general neurologists to optimally care for PwMS with busy office practices. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of add-on Nurse Practitioner (NP)-led care for PwMS on depression and anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS), compared to usual care (community neurologist, family physician).

Methods

PwMS followed by community neurologists were randomized to add-on NP-led or Usual care for 6 months. Primary outcome was the change in HADS at 3 months. Secondary outcomes were HADS (6 months), EQ5D, MSIF, CAREQOL-MS, at 3 and 6 months, and Consultant Satisfaction Survey (6 months).

Results

We recruited 248 participants; 228 completed the trial (NP-led care arm n = 120, Usual care arm n = 108). There were no significant baseline differences between groups. Study subjects were highly educated (71.05%), working full-time (41.23%), living independently (68.86%), with mean age of 47.32 (11.09), mean EDSS 2.53 (SD 2.06), mean duration since MS diagnosis 12.18 years (SD 8.82) and 85% had relapsing remitting MS. Mean change in HADS depression (3 months) was: -0.41 (SD 2.81) NP-led care group vs 1.11 (2.98) Usual care group p = 0.001, sustained at 6 months; for anxiety, − 0.32 (2.73) NP-led care group vs 0.42 (2.82) Usual care group, p = 0.059. Other secondary outcomes were not significantly different. There was no difference in satisfaction of care in the NP-led care arm (63.83 (5.63)) vs Usual care (62.82 (5.45)), p = 0.194).

Conclusion

Add-on NP-led care improved depression compared to usual neurologist care and 3 and 6 months in PwMS, and there was no difference in satisfaction with care. Further research is needed to explore how NPs could enrich care provided for PwMS in healthcare settings.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered on clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04388592, 14/05/2020).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is the leading cause of non-traumatic disability in young adults [1]. It is most commonly diagnosed in early to mid-adulthood, causing visible symptoms such as vision difficulties, gait troubles, weakness, coordination difficulties, and/or invisible symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive decline, depression, anxiety, bladder and bowel issues, sexual impairment, and pain [2, 3]. MS most commonly follows a relapsing-remitting course, ultimately transitioning into secondary progression MS as progression of disability advances, or following a progressive course from onset, identified as primary progressive MS. [4]. There is no cure for MS, and disability usually progresses over a person’s lifetime [2,3,4]. MS prevalence is increasing over time, with Canada having one of the highest incidence rates of MS in the world [1, 3]. Within Canada, Alberta has the highest prevalence of MS (340 per 100,000 population) [2], with 14,000 Albertans living with MS in 2013 [2].

Being diagnosed and living with MS is challenging, stressful, and unique for every person with MS and their caregivers; this requires individualized and ongoing support from healthcare providers and multi-disciplinary teams [5,6,7]. Timely access to specialized care is essential in diagnosing MS, monitoring disease, and managing people with MS (PwMS), as identified by an international expert group consensus around international quality standards of care for PwMS in 2019 [8]. Delays and difficulties in making appointments with neurologists have been identified as key barriers interfering with optimized care delivery to PwMS [9]. Indeed, in Canada, a recent online survey of Canadians living with MS (n = 324 responders) reported that 70% experienced challenges in obtaining appointments with their neurologists [10]. Even when meeting with healthcare providers, multiple studies reported that PwMS do not receive enough education or support from their health-care providers in order to meet their needs [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. This may be evolving in Canada, as suggested by Petrin et al. in 2021, where survey respondents expressed high levels of satisfaction with their healthcare providers around respectful communication and in shared decision making [25].

PwMS require decades of specialized neurologic care, with average life expectancy of one large Canadian cohort estimated to be approximately 6 years less than the general population [26]. A cross-sectional questionnaire study of 1205 PwMS identified unmet needs for PwMS as changing and evolving as their disability progresses [18]. Therefore, MS experts have emphasized that healthcare providers and services need to adapt to the different stages and health needs of PwMS – from early diagnosis to elderly patients [5, 8, 9, 18, 19]. This might be difficult to achieve in the current model of care where community general neurologists have very busy office practices [7, 27]. Specialized care within multi-disciplinary “MS Units”, including a specialized MS nurse as a key player within the team, has been suggested to fill these types of gaps [7].

A systematic review published in 2015 compared NP-led care to usual care for people with chronic diseases. Limited evidence inferred that NP involvement improved patient outcomes [27]. Some NP-led care trials utilized the NP instead of a physician specialist as a specialized, independent healthcare provider, backed up by a physician specialist [28,29,30]. In other trials, the NP worked as an add-on provider to the multi-disciplinary ambulatory care setting [31,32,33,34]. One randomized trial involving 122 participants with Parkinson’s disease compared outcomes of care delivered by a multi-disciplinary team (including a specialized nurse) to general neurologists over an eight-month period. Patients receiving care from the multi-disciplinary team reported improved scores on quality of life (QoL) and Parkinson’s scale outcomes [35].

Private-practice, community general neurologists and family physicians provide care for approximately 2000 PwMS outside of a multidisciplinary MS specialized clinic in northern Alberta, Canada. Usual care involves biannual to annual office visits, with variable referral to rehabilitation services and therapies, as determined by clinical judgement. Pressures on general neurologists and family physicians in busy office practices, combined with the treatment gaps and unmet needs of PwMS, underline the need for alternative ways to provide care. Adding a specialized MS NP as an additional healthcare provider to generalist neurology and primary care could potentially improve care for PwMS. Alternate specialized healthcare providers such as nurse practitioners (NPs) could be helpful in delivering care to PwMS in the Canadian healthcare setting. Further information about the NP model is available in the study protocol paper [36].

The primary objective was to evaluate the impact of an add-on NP-led care for PwMS and their caregivers on depression and anxiety levels.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a prospective parallel randomized controlled trial (RCT) with patients as the unit of randomization, with allocation ratio 1:1. The rationale and protocol for this RCT have been reported previously [36].

Setting

We included 7 community neurologist (CN) practices across Edmonton, Alberta, Canada and the tertiary MS Clinic at the University of Alberta Hospital.

Ethics approval

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Health Research Ethics Boards of the University of Alberta (approval number Pro00069595). This trial was registered retrospectively on clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04388592, 14/05/2020).

New clinical tools and procedures

The introduction of the NP into community general neurologist care for PwMS is novel. However, NP care for PwMS is standard at tertiary care centres and MS Clinics in optimizing care for PwMS.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants to participate in the study, prior to being randomized to participate within the study, and before completing baseline measures.

Population

Patients were included in the study if they were adults (≥ 18 years) who had a diagnosis of MS as per the McDonald 2010 criteria [37], were followed by a private-practice general neurologist and/or family doctor, willing to give consent, able to complete questionnaires and to attend outpatient visits with NP, English-speaking, and able to use a computer.

We excluded patients if they were unable to provide consent, unable or unwilling to attend appointments, referred to, or followed by neurologists within the tertiary setting, or had other central nervous system inflammation disorders.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through advertisements and computer tablets were placed in the waiting rooms of the seven CN practices. Interested patients completed the EQ5D [38] on a tablet and were encouraged to self-register for the study and discuss their results with their CN. We also accepted direct referrals from family physicians to the NP. Details about the recruitment process are available elsewhere [36]. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the trial.

Randomization and blinding

After being enrolled in the study, patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention or control groups [36]. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of providers or patients was not possible. The EPICORE Centre randomly randomized and allocated consented participants using a centralized secure website. Further details can be found in the study protocol publication [36].

Intervention

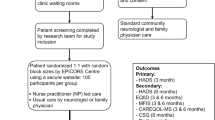

Patients in the intervention group received a comprehensive NP consultation. This included 1) patient history, 2) physical examination, 3) individualized symptomatic strategies (e.g., lifestyle strategies, mobility issues, fatigue, spasticity, bladder and bowel concerns, depression or anxiety, and medications) [39, 40], 4) exploration of the MS patient’s local community, 5) discussion of resources to optimize mood and QoL, and 6) regular follow up visits at 3, 6 months either in-person, via telehealth, or via phone call (Fig. 1). The NP carrying out the study intervention was mentored and trained by the experiences tertiary MS clinic NP, who has over 6 years of experience in MS, and the MS clinic subspecialist neurologists for a 3 month duration before the study was initiated, and 1 month after the study NP had worked in the community setting. In addition, the MS clinic NP and MS clinic subspecialist neurologists continued to be a resource for the study NP to contact with questions throughout the study duration. Please see the study protocol publication for further details [36].

Control

Patients randomized to the control group received usual care from CN practices, which included limited access to MS registered nurses (part of the tertiary MS clinic setting but going to community neurologists’ offices as outreach). This care was delivered according to standard practices. Some general neurologists participating in our study, did have the option of having registered nurses aid them on a designated day once per week. These registered nurses had limited scope of practice in the community neurologists’ offices of rooming patients with MS, updating medication lists, and helping the neurologists with disease-modifying therapy initiation and renewals. Due to the limited scope of support, the registered nurses did not have the resources or time to support the community neurologists in targeted symptom management strategies and lifestyle strategies such as bladder and bowel management, relapse management, delivery of comprehensive education to PwMS. Follow-up visits were conducted according to the individual standard care practices (Fig. 1). Patients in the control group were offered the NP intervention after 6 months.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference in change in HADS-D and HADS-A scores between intervention (NP-led care) and control (Usual care) groups at 3 months [38, 41, 42]. Secondary outcomes included difference in change in a) HADS-D and HADS-A scores at 6 months, b) EQ5D at 3 and 6 months [38], and c) Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) score at 3 and 6 months [43, 44], and patient satisfaction with care as measured by the validated Consultation Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) [45,46,47,48].

Sample size calculation

Using the information from Honarmand and Feinstein [41], [Baseline scores and standard deviation (SD)] and the following assumptions 80% power and a two-sided alpha of 0.025, a total sample size of 200 (100 in each group) was required to detect 1.5 difference [41] between the intervention and the control groups. We calculated the same size for both HADS-A and HADS-D and used the sample size for HADS-A, as it required a larger sample size and to ensure there was sufficient power for both HADS-A and HADS-D. This sample size was inflated to 220 to account for possible dropouts, losses to follow-up and withdrawals of consent.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using R 3.4.0 computer software (Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org/) and SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were reported using frequency and percentage and continuous variables were reported using mean (SD) or median [Interquartile range (IQR)] as appropriate. The primary outcome of difference in change of HADS-D and HADS-A from baseline to 3 months was analyzed using independent T-test. An independent T-test was also used to assess the difference in change between HADS-D and HADS-A between baseline and 6 months as well as the other questionnaires - EQ5D and MFIS. The CSQ Likert scales were analyzed as continuous variables, with the overall satisfaction score being calculated as a sum of the scales of each question and analyzed using an independent t-test to determine a difference between the intervention and control groups.

Data were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principles. Trial and Data Management was completed by EPICORE Centre (www.epicore.ualberta.ca).

Results

A total of 248 subjects were screened, of those, 234 were eligible to take part. All eligible patients provided informed consent and were enrolled in the study. Of those, 8 patients did not attend their baseline visit, and 226 patients completed the study and were included in the analysis (Fig. 2). Of note, although the study was open to PwMS followed primarily by either a community general neurologist, or a family physician, all participants in the study were followed by a general neurologist. Recruitment began on July 28, 2017 and was completed on March 3, 2019. The last participant in the study completed their surveys on Sept 25, 2019.

The 2 treatment groups were well balanced in baseline demographic and clinical parameters (Table 1). The mean age was 47.47 ± 11.02 years, 82.89% were female and 92.54% were white. More than two thirds of the participants were highly educated (71.05%) and living independently (68.86%), and less than half were working full time (41.23%).

Primary outcome

The mean difference in the change in HADS-D at 3 months was: -0.41 (SD 2.81) for the NP-led group vs 1.11 (2.98) Usual care group, p = 0.001 (Fig. 3); and for HADS-A, − 0.32 (2.73) NP-led group vs 0.42 (2.82) Usual care group, p = 0.059 (Fig. 4).

Secondary outcomes

At 6 months, the mean change in HADS-D was − 0.81 (SD 3.18) for the NP-led group vs 0.57 (SD 3.11) Usual care group, p = 0.003 (Fig. 4); and for HADS-A -0.46 (3.18) NP-led group vs 0.36 (2.55) Usual care group, p = 0.04 (Fig. 4).

The difference in mean change for MFIS and EQ5D were not statistically significant (Table 2). The mean change for MFIS at 3 months was − 0.31 (9.77) for the NP group vs 0.97 (10.6) for UC group, p = 0.54. The mean change for the EQ5D score at 3 months was 1.58 (14.5) for the NP group vs − 0.02 (14.99) for UC group, p = 0.54. The mean change at 6 months for the MFIS and EQ5D showed a similar trend but was also not statistically significant.

There was no difference in satisfaction with care between the NP and Usual care groups. The mean overall satisfaction score for the NP-led group was 63.83 (5.63) and for the Usual care group was 62.82 (5.45), with a p value of 0.194. No statistical differences were noted on any of the sub-scales between the two groups (Additional file 1: Appendix A).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of an “add-on” specialized MS NP-led care to PwMS in comparison to usual care through community neurologist and family physicians’ practices. We found that NP-led care was associated with improved depression levels for PwMS at 3 months, sustained at 6 months, compared to usual physician care. At 6 months, an improvement in anxiety was observed. This study suggests that NPs could address many of the unmet needs identified by PwMS [22, 23]: improved education, coping strategies, more timely and effective interventions, urgent relapse management, in addition to helping PwMS optimize their functioning.

We looked at depression and anxiety levels for PwMS as primary and secondary outcome measures over the short-term intervention of 3 and 6 months. We felt depression and anxiety levels might be the most responsive factors over the short-term in relation to participants’ quality of life (QoL). Depression has been reported to influence PwMS’ QoL in multiple studies [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Overall, PwMS have reported a lower QoL compared to the general population [49, 53, 54, 56]. Initiating interventions to depression and anxiety fit within the MS-specialized NP scope of practice [6, 59,60,61,62]; depression and possibly anxiety in PwMS can respond to pharmacologic, and non-pharmacologic strategies [63,64,65,66,67]. Our study showed that PwMS reported statistically improved depression scores at 3 months, sustained at 6 months, when an NP was added. Depression is common in PwMS with an estimated prevalence between 14 to 54%, and a pooled mean prevalence of 30.5% (95%CI 26.3–35.1%) of depression, and 22.1% (95% CI 15.2–31.9%) in one systematic review and meta-analysis [68]. There are mixed findings amongst researchers as to whether there is increased depression with increased disability [50, 69], or not [68, 70,71,72], but it is common even at the time of diagnosis [72]. Furthermore, both anxiety and depression have been shown to be under-recognized and undertreated in PwMS in Canada [58, 73]. Despite statistically significant improvements in depression and anxiety scores in our study, further research on the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) score for PwMS is needed before conclusions can be drawn about the clinical significance of these findings.

It has been suggested that NPs might be easier to access and less costly to see than physician health providers for PwMS [6, 74,75,76]. The use of specialized MS NPs in general neurology outpatient settings could potentially address some of these unmet needs that various researchers have identified including healthcare access [10, 11, 22, 77,78,79], education, counseling and support [13, 79], and support to informal caregivers of PwMS [13, 79,80,81]. The need for more specialized MS nursing care has been identified as integral to improving patient care delivery for PwMS [6, 82].

There was no difference in level of satisfaction by PwMS in being cared for by a specialized NP compared to usual care received from community neurologists. This is in line with what has reported in the literature where the MS nurse was identified as the preferred medical contact [24, 83, 84]. An audit of PwMS around MS specialized nurse care and impact upon QoL (55% response rate from 1350 questionnaires), revealed that 83% of respondents preferred the care of their MS related issues from the MS nurse over other health professionals [84]. When people with early stage MS were surveyed as to whom they received the best education about their illness and coping strategies, despite an overall identified deficiency of education, the closest to ideal amount of education was received from MS specialist nurses [16]. For those with progressive MS, the MS specialized nurse was identified as a key person and coordinator of care in meeting an identified need to provide a more comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to care, focusing on symptoms and QoL [6, 13, 61]. In 2015, a MS study found the establishment of proactive MS specialized nurse management in a primary-case based model with individualized care resulted in less emergency room visits and inpatient admissions over a 10 year period [85]. One prospective, randomized, controlled study assessed combined appointments with a multi-disciplinary MS Clinic team care, including a MS specialist nurse, vs standard care of referral to various specialists and allied health professionals as needed over a 6 month period for fifty moderately-disabled PwMS. They did not find differences in QoL measures, acknowledging that the overall care likely did not differ between arms, just in timing of visits [86].

This study provides an alternate and possibly cost-saving management strategy to complex management of symptoms and QoL measures for PwMS. These findings corroborate other studies identifying the benefits of NP patient care [27, 74, 75, 85], however, despite the magnitude of change in depression levels being statistically significant, it may not be to clinically meaningful levels. It is possible that there would have been greater change seen if participants had been primarily cared for by family physicians; 12.3% of 324 respondents in a recent survey of Canadians living with MS indicated that they received the majority of their care from general practitioners, 4% received no care for their MS, while 8% received their MS care primarily from walk-in clinics, after-hours clinics and emergencies [25].

Limitations

The patients involved in this study self-reported their data which could be susceptible to subjective bias. Participants presumably participated in the study if they were open to being treated by an NP in addition to their CN, likely viewing NP positively, which could impact the finding of similar consultant satisfaction between arms. However, despite the potential bias, the findings of our study are consistent with what has been reported in the literature. Even though we opened the study to PwMS followed by general community neurologists or family physicians, all of the study participants were followed by a general neurologist. This is likely due to the methods of recruitment, primarily based within community neurologists’ office. Future studies could examine the value of an MS specialized NP in specialist and primary care settings. The control arm for our study included limited support to community neurologists by registered nurses who also work within a tertiary MS clinic setting. Due to the limited resources and time that the registered nurses could provide to the community neurologists, the registered nursing support consisted only of rooming patients, updating medication lists, and aiding in disease-modifying therapy access and renewals. Therefore, the registered nurses did not provide interventions provided by the nurse practitioner in the active arm of symptomatic strategies, lifestyle strategies etc. It is likely that a trained registered nurse could perform some of the duties performed by the NP in our study. However, as outlined in the study protocol paper in Trials, the NP provided an independent and holistic approach to study participants, including independent referrals to community resources, independent ordering of investigations and prescription of symptomatic medications [36]. Time was a limitation of this study, as 6 months may not be adequate time to see a significant change in a patient’s HADS, MFIS, or EQ5D. However, despite the short duration, this study showed an encouraging trend that NP-led care can positively influence or delay the decline of QoL measures such as depression for PwMS.

Generalizability of study findings

Our study is generalizable to other healthcare settings, where generalists such as family doctors and general neurologists care for PwMS outside of a tertiary MS-subspecialty clinic. We did not examine the add-on aspects to NP-led care in the MS subspecialty clinic settings. We carried out our study with PwMS in a public healthcare system in Canada. However, there are similar challenges in meeting care needs of other chronic diseases in any healthcare system.

Sex and gender

Our study did not select for participants, considering their sex and gender. Consecutive prospective participants visiting their community neurologists’ offices were approached to participate in the study. Prospective participants consented and were randomized after consent to participate in either arm. However, 82% of the participants were of female sex; this reflects the female preponderance to getting MS in comparison to males, and is consistent with other studies examining MS within populations. Gender was not collected in our study, and is a limitation of our study. Going forward, future clinical trials examining NP involvement in care for PwMS should examine if there are differences in consultant satisfaction by gender in receiving care from an NP.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that adding a specialized NP to the care of PwMS improved depression over three and 6 months. There were no differences seen in satisfaction of care received by an NP as participants’ usual care. Examining the effect of a NP in a CN setting, delivering care to PwMS through multi-disciplinary means, such as through a patient advocacy management model [87], holds potential to improve symptoms for PwMS, improving healthcare access and satisfaction, and QoL for PwMS and their caregivers. In pressured public healthcare systems, alternate ways of supporting and treating PwMS need to be explored and supported to optimize the experience and functioning of PwMS.

Availability of data and materials

All data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Due to regulations from our Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta around confidentiality and storage of the data obtained from the study, we are unable to share raw data in a public forum. Requests for raw data access will be reviewed for approval by the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board before release (Ethics approval number Pro00069595).

Abbreviations

- HADS-A:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety score

- HADS-D:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Depression score

- MS:

-

Multiple Sclerosis

- NP:

-

Nurse practitioner

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- PwMS:

-

People with MS

- CSQ:

-

Consultation Satisfaction Questionnaire

- CN:

-

Community neurologists

References

Browne P, Chandraratna D, Angood C, Tremlett H, Baker C, et al. Atlas of multiple sclerosis 2013: a growing global problem with widespread inequity. Neurology. 2014;83(11):1022–4.

The way forward: Alberta's multiple sclerosis partnership: [https://open.alberta.ca/publications/9781460108574] 2013. Accessed on 11 Apr 2022.

Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, Kaye W, Leray E, Marrie RA, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler. 2020;26(14):1816–1821.2020.

Oh J, Vidal-Jordana A, Montalban X. Multiple sclerosis: clinical aspects. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018;31(6):752–9.

Members of the MS in the 21st Century Steering Group, Rieckmann P, Centonze D, Elovaara I, Giovannoni G, Havrdova E, et al. Unmet needs, burden of treatment, and patient engagement in multiple sclerosis: A combined perspective from the MS in the 21st Century Steering Group. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;19:153–60.

Meehan M, Doody O. The role of the clinical nurse specialist multiple sclerosis, the patients' and families' and carers' perspective: an integrative review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;39:101918.

Soelberg Sorensen P, Giovannoni G, Montalban X, Thalheim C, Zaratin P, Comi G. The multiple sclerosis care unit. Mult Scler. 2019;25(5):627–36.

Hobart J, Bowen A, Pepper G, Crofts H, Eberhard L, Berger T, et al. International consensus on quality standards for brain health-focused care in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019;25(13):1809–18.

Giovannoni G, Butzkueven H, Dhib-Jalbut S, Hobart J, Kobelt G, Pepper G, et al. Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9(Suppl 1):S5–S48.

Petrin J, McColl MA, Donnelly C, French S, Finlayson M. Prioritizing the healthcare access concerns of Canadians with MS. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2021;7(3):20552173211029672.

Borreani C, Bianchi E, Pietrolongo E, Rossi I, Cilia S, Giuntoli M, et al. Unmet needs of people with severe multiple sclerosis and their carers: qualitative findings for a home-based intervention. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109679.

Buchanan RJ, Huang C. Informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis: factors associated with the strength of the caregiver/care recipient relationship. Int J MS Care. 2011;13(4):177–87.

Holland NJ, Schneider DM, Rapp R, Kalb RC. Meeting the needs of people with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, their families, and the health-care community. Int J MS Care. 2011;13(2):65–74.

Le Fort M, Wiertlewski S, Bernard I, Bernier C, Bonnemain B, Moreau C, et al. Multiple sclerosis and access to healthcare in the pays de la Loire region: preliminary study based on 130 self-applied double questionnaires. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;54(3):156–71.

Lorefice L, Mura G, Coni G, Fenu G, Sardu C, Frau J, et al. What do multiple sclerosis patients and their caregivers perceive as unmet needs? BMC Neurol. 2013;13:177.

Matti AI, McCarl H, Klaer P, Keane MC, Chen CS. Multiple sclerosis: patients' information sources and needs on disease symptoms and management. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010;4:157–61.

Mehr SR, Zimmerman MP. Reviewing the unmet needs of patients with multiple sclerosis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(8):426–31.

Ponzio M, Tacchino A, Zaratin P, Vaccaro C, Battalglia MA. Unmet care needs of people with a neurological chronic disease: a cross-sectional study in Italy on multiple sclerosis. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25(5):775–80.

Solaro C, Ponzio M, Moran E, Tanganelli P, Pizio R, Ribizzi G, et al. The changing face of multiple sclerosis: prevalence and incidence in an aging population. Mult Scler. 2015;21(10):1244–50.

Strupp J, Romotzky V, Galushko M, Golla H, Voltz R. Palliative care for severely affected patients with multiple sclerosis: when and why? Results of a Delphi survey of health care professionals. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(10):1128–36.

Young L, Healey K, Charlton M, Schmid K, Zabad R, Wester R. A home-based comprehensive care model in patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A study pre-protocol. F1000Res. 2015;4:872.

Ponzio M, Tacchino A, Vaccaro C, Brichetto G, Battaglia MA, Messmer UM. Disparity between perceived needs and service provision: a cross-sectional study of Italians with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(6):1137–44.

Ponzio M, Tacchino A, Vaccaro C, Traversa S, Brichetto G, Battaglia MA, et al. Unmet needs influence health-related quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;38:101877.

Forbes A, While A, Taylor M. What people with multiple sclerosis perceive to be important to meeting their needs. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(1):11–22.

Petrin J, Finlayson M, Donnelly C, McColl MA. Healthcare access experiences of persons with MS explored through the candidacy framework. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29(3):789–99.

Kingwell E, van der Kop M, Zhao Y, Shirani A, Zhu F, Oger J, et al. Relative mortality and survival in multiple sclerosis: findings from British Columbia. Canada J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(1):61–6.

Martin-Misener R, Harbman P, Donald F, Reid K, Kilpatrick K, Carter N, et al. Cost-effectiveness of nurse practitioners in primary and specialised ambulatory care: systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007167.

Schuttelaar ML, Vermeulen KM, Drukker N, et al. A randomized controlled trial in children with eczema: nurse practitioner vs. dermatologist. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(1):162–70.

Schuttelaar ML, Vermeulen KM, Coenraads PJ. Costs and cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment in children with eczema by nurse practitioner vs. dermatologist: results of a randomized, controlled trial and a review of international costs. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(3):600–11.

Limoges-Gonzalez M, Mann NS, Al-Juburi A, Tseng D, Inadomi J, Rossaro L. Comparisons of screening colonoscopy performed by a nurse practitioner and gastroenterologists: a single-center randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2011;34(3):210–6.

Allen JK, Blumenthal RS, Margolis S, Young DR, Millier ER 3rd, Kelly K. Nurse case management of hypercholesterolemia in patients with coronary heart disease: results of a randomized clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2002;144(4):678–86.

Paez KA, Allen JK. Cost-effectiveness of nurse practitioner management of hypercholesterolemia following coronary revascularization. J Amer Acad of Nurs Pract. 2006;18(9):436–44.

Krein SL, Klamerus ML, Vijan S, Lee JL, Fitzgerald JT, Pawlow A, et al. Case management for patients with poorly controlled diabetes: a randomized trial. Am J Med. 2004;116(11):732–9.

Litaker D, Mion L, Planavsky L, Kippes C, Mehta N, Frolkis J. Physician - nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: the impact on costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients' perception of care. J Interprof Care. 2003;17(3):223–37.

van der Marck MA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, Overeem S, Munneke M, Guttman M. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for Parkinson's disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2013;28(5):605–11.

Smyth P, Watson KE, Tsuyuki RT. Measuring the effects of nurse practitioner (NP)-led care on depression and anxiety levels in people with multiple sclerosis: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):785.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):292–302.

Kuspinar A, Mayo NE. A review of the psychometric properties of generic utility measures in multiple sclerosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(8):759–73.

Ziemssen T. Symptom management in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2011;311(Suppl 1):S48–52.

Crabtree-Hartman E. Advanced symptom Management in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2018;36(1):197–218.

Honarmand K, Feinstein A. Validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale for use with multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2009;15(12):1518–24.

Puhan MA, Frey M, Büchi S, Schunemann HJ. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:46.

Fisk JD, Ritvo PG, Ross L, Haase DA, Marrie TJ, Schlech WF. Measuring the functional impact of fatigue: initial validation of the fatigue impact scale. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(Suppl 1):S79–83.

Fisk JD, Pontefract A, Ritvo PG, Archibald CJ, Murray TJ. The impact of fatigue on patients with multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 1994;21(1):9–14.

Shaida N, Jones C, Ravindranath N, Das T, Wilmott K, Jones A, et al. Patient satisfaction with nurse-led telephone consultation for the follow-up of patients with prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10(4):369–73.

Baker R. Development of a questionnaire to assess patients' satisfaction with consultations in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(341):487–90.

Baker R, Whitfield M. Measuring patient satisfaction: a test of construct validity. Qual Health Care. 1992;1(2):104–9.

Smigorowsky MJ, Norris CM, McMurtry MS, Tsuyuki RT. Measuring the effect of nurse practitioner (NP)-led care on health-related quality of life in adult patients with atrial fibrillation: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):364.

Kuspinar A, Rodriguez AM, Mayo NE. The effects of clinical interventions on health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2012;18(12):1686–704.

Janssens AC, van Doorn PA, de Boer JB, Kalkers NF, van der Meche FG, Passchier J, et al. Anxiety and depression influence the relation between disability status and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003;9(4):397–403.

Brenner P, Piehl F. Fatigue and depression in multiple sclerosis: pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;134(Suppl 200):47–54.

McKay KA, Tremlett H, Fisk JD, Zhang T, Patten SB, Kastrukoff L, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2018;90(15):e1316–23.

McKay KA, Ernstsson O, Manouchehrinia A, Olsson T, Hillert J. Determinants of quality of life in pediatric- and adult-onset multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2020;94(9):e932–41.

Biernacki T, Sandi D, Kincses ZT, Fuvesi J, Rozsa C, Matyas K, et al. Contributing factors to health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav. 2019;9(12):e01466.

Pugliatti M, Riise T, Nortvedt MW, Carpentras G, Sotgiu MA, Sotgui S, et al. Self-perceived physical functioning and health status among fully ambulatory multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol. 2008;255(2):157–62.

Rudick RA, Miller D, Clough JD, Gragg LA, Farmer RG. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Comparison with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 1992;49(12):1237–42.

Marrie RA, Walld R, Bolton JM, Sareen J, Patten SB, Singer A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity increases mortality in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;53:65–72.

Marrie RA, Patten SB, Berrigan LI, Tremlett H, Wolfson C, Warren S, et al. Diagnoses of depression and anxiety versus current symptoms and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(2):76–84.

Forbes A, While A, Dyson L, Grocott T, Griffiths P. Impact of clinical nurse specialists in multiple sclerosis--synthesis of the evidence. J Adv Nurs 2003;42(5):442–462.

Maloni HW. Multiple sclerosis: managing patients in primary care. Nurse Pract. 2013;38(4):24–35 quiz 35-26.

Maloni H, Hillman L. Multidisciplinary Management of a Patient with Multiple Sclerosis: part 2. Nurses’ Perspective Fed Pract. 2015;32(Suppl 3):17S–9S.

Roman C, Menning K. Treatment and disease management of multiple sclerosis patients: a review for nurse practitioners. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29(10):629–38.

Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, Otero-Romero S, Amato MP, Chandraratna D, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96–120.

Patten SB, Marrie RA, Carta MG. Depression in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):463–72.

Fiest KM, Walker JR, Bernstein CN, Graff LA, Zarychanski R, Abou-Setta AM, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions for depression and anxiety in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;5:12–26.

Hind D, Cotter J, Thake A, Bradburn M, Cooper C, Isaac C, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of depression in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:5.

Kidd T, Carey N, Mold F, Westwood S, Miklaucich M, Konstantara E, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of self-management interventions in people with multiple sclerosis at improving depression, anxiety and quality of life. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185931.

Boeschoten RE, Braamse AMJ, Beekman ATF, Cuijpers P, van Oppen P, Dekker J, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2017;372:331–41.

Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Sullivan M, Bowen JD, Kraft GH. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1862–8.

Zabad RK, Patten SB, Metz LM. The association of depression with disease course in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(2):359–60.

Koch MW, Patten S, Berzins S, Zhornitsky S, Greenfield J, Wall W, et al. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a long-term longitudinal study. Mult Scler. 2015;21(1):76–82.

Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J, Stuve O, Trojano M, Sorensen PS, et al. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2015;21(3):305–17.

Raissi A, Bulloch AG, Fiest KM, McDonald K, Jette N, Patten SB. Exploration of Undertreatment and patterns of treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(6):292–300.

Trilla F, DeCastro T, Harrison N, Mowry D, Croke A, Bicket M, et al. Nurse practitioner home-based primary care program improves patient outcomes. J Nurse Pract. 2018;14:e185–8.

Melnick G, Green L, Rich J. House calls: California program for homebound patients reduces monthly spending, delivers meaningful care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):28–35.

Buerhaus P. Nurse practitioners: a solution to America’s primary care crisis. American Enterprise Institute 2018 [https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/nurse-practitioners-asolution-to-americas-primary-care-crisis/] Accessed on 2 Mar 2022.

Lonergan R, Kinsella K, Fitzpatrick P, Duggan M, Jordan S, Bradley D, et al. Unmet needs of multiple sclerosis patients in the community. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(2):144–50.

Pétrin J, Donnelly C, McColl MA, Finlayson M. Is it worth it?: the experiences of persons with multiple sclerosis as they access health care to manage their condition. Health Expect. 2020;23(5):1269–79.

McCabe MP, Ebacioni KJ, Simmons R, McDonald E, Melton L. Unmet education, psychological and peer support needs of people with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(1):82–7.

Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Huang C. Caregiver burden among informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011;13(2):76–83.

Buchanan R, Huang C. Health-related quality of life among informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(2):113–21.

Mynors G, Suppiah J, Bowen A. Evidence for MS specialist services: findings from the GEMSS MS specialist nurse evaluation project 2015. Multiple Sclerosis Trust Website [https://mstrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/GEMSS%20final%20report.pdf] Accessed on 2 Mar 2022.

Somerset M, Campbell R, Sharp DJ, Peters TJ. What do people with MS want and expect from health-care services? Health Expect. 2001;4(1):29–37.

Ward-Abel N, Mutch K, Huseyin H. Demonstrating that multiple sclerosis specialist nurses make a difference to patient care. British J Neurosci Nurs. 6(7):319–24 [https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/bjnn.2010.6.7.79225] Accessed on 2 Mar 2022.

Leary A, Quinn D, Bowen A. Impact of proactive case management by multiple sclerosis specialist nurses on use of unscheduled care and emergency presentation in multiple sclerosis: a case study. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(4):159–63.

Papeix C, Gambotti L, Assouad R, Ewencyck C, Tanguy ML, Pineau F, et al. Evaluation of an integrated multidisciplinary approach in multiple sclerosis care: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Mult Scler J. 2015;1:2055217315608864.

Wynia K, Annema C, Nissen H, De Keyser J, Middel B. Design of a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) on the effectiveness of a Dutch patient advocacy case management intervention among severely disabled multiple sclerosis patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:142.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Shantha George and Margaret Prociuk for their expertise and contributions as nurse practitioners with contribution to study design. Additionally, we wish to thank the community neurologists who participated in the study, and gave input to study design: Dr. Mary Lou Myles, Dr. Ken Makus, Dr. Jodi Kashmere, Dr. Rob Pokroy, Dr. Bert Witt, Dr. Adam Witt, and Dr. Bradley Stewart, in addition to their office staff who coordinated NP visits. We thank the EPICORE Centre research team in contributing greatly to study design, data management, and biostatistical analyses. We thank the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) through Alberta Innovates and CIHR for funding in addition to the University Hospital Foundation. We thank Alberta Health Services for supporting the clinical trial in the clinical setting.

New clinical tools and procedures

The introduction of the NP into community general neurologist care for PwMS is novel. However, NP care for PwMS is standard at tertiary care centres and MS Clinics in optimizing care for PwMS.

Funding

Funding was provided through the University Hospital Foundation (RES0013590) and partially matched by the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research, Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS – co-principal investigator, created the study protocol, ethics submission, lead author on paper, edited and revised manuscript. KW – study protocol, ethics re-submission with study extension, wrote manuscript first draft, edited and revised manuscript. YA – contributed to study protocol, creation and maintenance of study database, interpretation of study findings, edited and revised manuscript. RT – co-principal investigator on the study, created the study protocol, database management, edited and revised manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Health Research Ethics Boards of the University of Alberta (approval number Pro00069595). This trial was registered retrospectively on clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04388592, 14/05/2020).

Informed consent was obtained from all participants to participate in the study, prior to being randomized to participate within the study, and before completing baseline measures.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

P. Smyth has received grant support through CIHR and the MS Society of Canada and is a co-investigator in a study funded by an unrestricted research grant from Biogen pharmaceuticals. She has consulted on advisory boards for Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Roche Canada, Biogen Idec Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Genzyme Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers-Squibb Pharmaceuticals, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Alberta Blue Cross and the Short-Term Exceptional Drug Therapy Program for Alberta Health Services.

K. Watson has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Y. Hamarneh has no conflicts of interest to declare.

R. Tsuyuki has done consulting for Emergent BioSolutions and Shoppers Drug Mart and has received investigator-initiated research grants from Sanofi, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Smyth, P., Watson, K.E., Al Hamarneh, Y.N. et al. The effect of nurse practitioner (NP-led) care on health-related quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis – a randomized trial. BMC Neurol 22, 275 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02809-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02809-9