Abstract

Background

Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis is the most frequent autoimmune paraneoplastic encephalitis, and is primarily associated with ovarian teratomas. Here, we report the first case of a patient diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) during the recovery phase of anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Case presentation

The patient was admitted with fever, headache, and seizures. Brain MRI revealed a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-containing arachnoid cyst in the left temporal lobe with no other abnormal signals. EEG showed diffuse background slowing in the delta-theta range. The patient tested positive for anti-NMDAR antibodies in both the serum and CSF. One year after the onset of encephalitis, the patient was referred to the Department of Hematology for extreme leukocytosis. Karyotype analysis showed the presence of Philadelphia chromosome t(9;22)(q34;q11). Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR analysis further identified BCR/ABL1 fusion transcripts; thus, CML was diagnosed.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of anti-NMDAR encephalitis associated with CML. This report should alert clinicians to consider CML as a malignancy that is possibly associated with limbic encephalitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis is a type of autoimmune limbic encephalitis characterized by a variety of symptoms, including memory loss, seizures, movement abnormalities, autonomic instability, paranoia, delusions, and catatonia. Dalmau et al. first identified in 2007 that anti-NMDAR encephalitis was caused by autoantibodies targeting the NMDA receptor in the brain [1, 2]. Anti-NMDAR encephalitis can present as an independent non-paraneoplastic disorder, or a paraneoplastic syndrome [3]. As the most frequent autoimmune encephalitis, anti-NMDAR encephalitis is reported to be associated with ovarian teratomas and other malignancies [2, 4,5,6]. Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is a malignancy of the myeloid cell lineage genetically characterized by the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome [t(9;22)(q34;q11)], which generates the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene [7]. Here, we report the first case of a patient who was diagnosed with CML during the recovery phase from anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Case presentation

Here we present the case of a previously healthy, right-handed 23-year-old man. The chief complaints were fever and headache for two days, accompanied by vomiting. He developed one episode of generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS), for which he was admitted to our hospital.

On admission, he further exhibited focal seizures, anxiety symptoms, sweating, sleep disturbance, and amnesia. He was conscious and oriented toward time, place, and person. His vital signs were within the normal limits. Examination revealed neck stiffness, and his neurological status was normal. A general medical examination revealed no abnormal findings.

Lumbar puncture was performed after admission. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure was 220 mmH2O. Bacterial, tuberculosis, and fungal cultures were negative. IgM antibodies for cytomegalovirus, rubella virus, herpes simplex virus, parvovirus B19, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, varicella-zoster virus, and mumps virus were negative. The oligoclonal band was negative in both the CSF and serum. The CSF nucleated cell count was 10 × 106 cells/L (0–8 × 106/L). The red cell count was 3200 × 106 cells/L (< 0/L). The total protein level was 181 mg/L (150–450 mg/L) and the albumin level was 95 mg/L (100–300 mg/L). Glucose, electrolyte, and LDH levels were within the normal limits.

Extensive laboratory evaluation revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 16.31 × 109/L (3.5–9.5 × 109/L), myoglobin count of 160.9 ng/mL (< 154.9 ng/mL), creatine kinase level of 3447 U/L (< 190U/L) and C-reactive protein level of 10.5 mg/L (< 1 mg/L). The following tests showed no abnormalities: hemoglobin, platelet count, D-D dimer, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thyroid stimulating hormone, free T3, free T4, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies panel, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis.

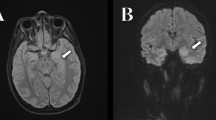

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence and enhanced scanning, revealed a CSF-containing arachnoid cyst in the left temporal lobe, while no other abnormal signals were observed (Fig. 1). EEG showed a diffuse background slowing in the delta-theta range. Chest CT did not reveal any abnormalities. Ultrasound examinations of the heart, liver, gallbladder, spleen, pancreas, kidneys, ureters, bladder, and testis were normal.

A profile of autoimmune encephalitis was obtained. The patient tested positive for anti-NMDAR antibodies both in serum and the CSF (titer 1:100 and 1:32, respectively; using a cell-based immunofluorescence assay), and a diagnosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis was considered.

He received high-dose intravenous corticosteroids, followed by intravenous immunoglobulin, after which symptoms, such as fever and insomnia, started to improve. Oral corticosteroids were subsequently introduced and gradually reduced; however, severe attention disturbance and amnesia persisted, and tacrolimus was added. Four months after the initial treatment, the patient was almost completely symptom-free. During the visit, his blood tacrolimus fluctuated from 4.1 to 11.37 ng/mL, and the white blood cell count ranged from 8.11 to 12.73 × 109/L (3.5–9.5 × 109/L). However, 1 year after the onset of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, routine blood examination revealed a markedly elevated white blood cell count of 119.18 × 109/L (3.5–9.5 × 109/L), confirmed on repeat test to be 124.69 × 109/L. He was then referred to our department of hematology for evaluation of extreme leukocytosis.

On admission, the patient denied fatigue, weakness, abdominal pain, digital pain, multiple arthralgia, or bleeding. A physical examination performed at the Department of Hematology revealed no abnormalities. The patient's abdomen was not distended, and the spleen was not palpable.

Besides hyperleukocytosis, the peripheral blood counts were as follows: hemoglobin level 151 g/L (130–175 g/L), platelets 166.0 × 109/L (125–350 × 109/L). Laboratory analyses of the blood were normal for ANA, ANCA, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, creatinine, urea, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, and total proteins. Serum ferritin levels were high at 1880.9 ng/mL (30–400 ng/mL), and lactate dehydrogenase was 1740 U/L (135–225 U/L). C-reactive protein level was positive at 5.2 mg/L (< 1 mg/L).

Six metaphases were assessed for karyotype analysis from the bone marrow specimen, all of which showed the classic Philadelphia chromosome resulting from t(9;22)(q34;q11) (Fig. 2). Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR analysis identified BCR/ABL1 fusion transcripts with a predominant p210 transcript at a BCR/ABL ratio of approximately 215.47%. CML was diagnosed, and treatment with hydroxyurea was initiated.

Discussion and conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of anti-NMDAR encephalitis associated with CML. The diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) include cancer that presents within the next 5 years, classical or non-classical neurological syndromes, and positive neuronal antibodies [8]. PLE is most commonly associated with small cell lung carcinomas and testicular germ cell tumors [9]. It may also be due to teratomas, thymomas, bladder cancers, and breast cancers [9]. Regarding hematological malignancies, Hodgkin’s lymphoma is the most common cause of PLE, while T-cell lymphoma, chronic lymphoid leukemia, and acute myelogenous leukemia have also been reported [9,10,11,12]. To the best of our knowledge, no case of CML with PLE has been reported to date.

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis is a form of limbic encephalitis that can be either paraneoplastic or nonparaneoplastic [13]. The NMDA receptor is a glutamate receptor primarily expressed in the cerebral cortex and hypothalamus [14]. As the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, glutamate is involved in cognitive functions such as learning and memory [15]. Infection, inflammation, and neoplasms can initiate molecular mimicry of the NMDA receptor, which in turn results in a mistaken attack on the healthy brain tissue [16,17,18]. Studies have suggested that viral infection can induce neuroinflammation, leading to anti-NMDAR antibody production [19]. Herpes simplex is the most commonly identified trigger of the encephalitic autoimmune response, and several studies have reported associations between anti-NMDAR encephalitis and other viruses or bacteria [20]. Despite extensive testing, no specific cause of antibody formation after infection has been identified. Approximately 20–40% of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis have an associated tumor, and the main tumor type is ovarian teratoma, which expresses NMDAR [21,22,23]. Testicular immature teratoma and lymphoma are also found to be associated with anti-NMDAR encephalitis [21, 24]. However, further investigation is required to determine the cause of NMDAR autoantibody formation and its correlation with malignancy.

The pathogenesis of CML is multifactorial, and genetic, metabolic, and immunological factors appear to play critical roles [25]. Autoimmune diseases are mainly characterized by T cell lymphocytes reactive with host antigens or B cell-forming autoantibodies against host antigens [16]. Studies have demonstrated that many autoimmune diseases are associated with CML, including Guillain–Barré syndrome, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis [26, 27]. Regarding the mechanisms involved, abnormally proliferating monocytes and further dysregulation of the T cell population are assumed to play an important role [28]. Further studies are required to explore the exact role of monocytes in patients with coexisting anti-NMDAR encephalitis and CML. In addition, accumulating evidence has suggested that autoimmune diseases might trigger hematological malignancies due to a common genetic predisposition. For example, human leukocyte antigen (HLA-B27) is associated with the etiology of autoimmune diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis and amyloidosis, and recent studies have suggested that HLA-B27 carriers may be predisposed to lymphoid malignancies [29, 30]. It is therefore possible that such a link may exist between anti-NMDAR encephalitis and CML. However, further studies are required to clarify this point.

Overall, we report the first case of a patient diagnosed with CML one year after the onset of anti-NMDAR encephalitis. It is still unclear as to whether CML is correlated with anti-NMDAR encephalitis, or developed simply by coincidence. Although more cases and studies are required to support a causal relationship, it may be prudent to consider the alternative explanation that the patient coincidentally developed anti-NMDAR encephalitis of unknown cause and CML within five years of disease symptom onset. Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor that can be used as a graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in hematological malignancies, such as CML. This treatment exerts adverse effects on the hematological system, including anemia, leukopenia, leukocytosis, and thrombocytopenia [31, 32]. To date, no CML attributed to tacrolimus has yet been reported. This report should alert clinicians to consider CML as a malignancy potentially associated with limbic encephalitis. For patients diagnosed with anti-NMDAR encephalitis, continuous routine blood tests should also be recommended. We look forward to developing studies to answer important questions regarding the mechanisms involved.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NMDAR:

-

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PLE:

-

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis

- CML:

-

Chronic myelogenous leukemia

- Ph:

-

Philadelphia

- GTCS:

-

Generalised tonic clonic seizures

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalogram

- ANA:

-

Antinuclear antibodies

- ANCA:

-

Anti-Neutrophil cytoplasm autoantibodies

- HLA:

-

Human leucocyte antigen

References

Ances BM, Vitaliani R, Taylor RA, Liebeskind DS, Voloschin A, Houghton DJ, et al. Treatment-responsive limbic encephalitis identified by neuropil antibodies: MRI and PET correlates. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 8):1764–77.

Dalmau J, Tuzun E, Wu HY, Masjuan J, Rossi JE, Voloschin A, et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(1):25–36.

Neyens RR, Gaskill GE, Chalela JA. Critical care management of Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor encephalitis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):1514–21.

Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, Armangue T, Glaser C, Iizuka T, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157–65.

Kayser MS, Titulaer MJ, Gresa-Arribas N, Dalmau J. Frequency and characteristics of isolated psychiatric episodes in anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(9):1133–9.

Lancaster E. The diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune encephalitis. J Clin Neurol. 2016;12(1):1–13.

Radich J, Yeung C, Wu D. New approaches to molecular monitoring in CML (and other diseases). Blood. 2019;134(19):1578–84.

Graus F, Delattre JY, Antoine JC, Dalmau J, Giometto B, Grisold W, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(8):1135–40.

Gultekin SH, Rosenfeld MR, Voltz R, Eichen J, Posner JB, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: neurological symptoms, immunological findings and tumour association in 50 patients. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 7):1481–94.

Dogel D, Beuing O, Koenigsmann M, Diete S. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis resulting from non-Hodgkin-lymphoma: two case reports. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2008;76(1):41–6.

Rajappa S, Digumarti R, Immaneni SR, Parage M. Primary renal lymphoma presenting with paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3783–5.

Arcani R, Jean E, Pozzo Di Borgo J, Lamarchi JF, Venton G, Veit V. Anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis associated with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;189:105618.

Scheer S, John RM. Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor encephalitis in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016;30(4):347–58.

Masghati S, Nosratian M, Dorigo O. Anti-N-methyl-aspartate receptor encephalitis in identical twin sisters: role for oophorectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 2 Suppl 2):433–5.

Lazar-Molnar E, Tebo AE. Autoimmune NMDA receptor encephalitis. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;438:90–7.

Levin MC, Lee SM, Kalume F, Morcos Y, Dohan FC Jr, Hasty KA, et al. Autoimmunity due to molecular mimicry as a cause of neurological disease. Nat Med. 2002;8(5):509–13.

Dalmau J, Armangué T, Planagumà J, Radosevic M, Mannara F, Leypoldt F, et al. An update on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis for neurologists and psychiatrists: mechanisms and models. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):1045–57.

Lynch DR, Rattelle A, Dong YN, Roslin K, Gleichman AJ, Panzer JA. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: clinical features and basic mechanisms. Adv Pharmacol. 2018;82:235–60.

Armangue T, Spatola M, Vlagea A, Mattozzi S, Carceles-Cordon M, Martinez-Heras E, et al. Frequency, symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes of autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: a prospective observational study and retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):760–72.

Makuch M, Wilson R, Al-Diwani A, Varley J, Kienzler AK, Taylor J, et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody production from germinal center reactions: therapeutic implications. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(3):553–61.

Leypoldt F, Wandinger KP. Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175(3):336–48.

Iorio R, Spagni G, Masi G. Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36(4):279–92.

Wu CY, Wu JD, Chen CC. The Association of Ovarian Teratoma and Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis: an updated integrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(20):10911.

Dabner M, McCluggage WG, Bundell C, Carr A, Leung Y, Sharma R, et al. Ovarian teratoma associated with anti-N-methyl D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: a report of 5 cases documenting prominent intratumoral lymphoid infiltrates. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2012;31(5):429–37.

Tefferi A, Hoagland HC, Therneau TM, Pierre RV. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: natural history and prognostic determinants. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64(10):1246–54.

Hemminki K, Liu X, Forsti A, Ji J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Subsequent leukaemia in autoimmune disease patients. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(5):677–87.

Gunnarsson N, Hoglund M, Stenke L, Wallberg-Jonsson S, Sandin F, Bjorkholm M, et al. Increased prevalence of prior malignancies and autoimmune diseases in patients diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(7):1562–7.

Peker D, Padron E, Bennett JM, Zhang X, Horna P, Epling-Burnette PK, et al. A close association of autoimmune-mediated processes and autoimmune disorders with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: observation from a single institution. Acta Haematol. 2015;133(2):249–56.

Au WY, Hawkins BR, Cheng N, Lie AK, Liang R, Kwong YL. Risk of haematological malignancies in HLA-B27 carriers. Br J Haematol. 2001;115(2):320–2.

Sheehan NJ. HLA-B27: what’s new? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(4):621–31.

Yoshikawa H, Kiuchi T, Saida T, Takamori M. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tacrolimus in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(9):970–7.

Wang L, Zhang S, Xi J, Li W, Zhou L, Lu J, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus for myasthenia gravis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2017;264(11):2191–200.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank our patient for allowing the publication of this case report.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY and DST carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. DST participated in its design. JLL participated in the acquisition and analysis or interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The patient provided his written informed consent to participate in this study and to the publication of this case report.

Consent for publication

We have obtained written informed consent from the patient for the publication of this case report and image.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Y., Liu, JL. & Tian, DS. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with chronic myelogenous leukemia, causality or coincidence? A case report. BMC Neurol 22, 153 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02675-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02675-5