Abstract

Background

It is common for people with persistent spasticity due to a stroke to receive an injection of botulinum toxin-A in the upper limb, however post-injection intervention varies.

Aim

To determine the long-term effect of additional upper limb rehabilitation following botulinum toxin-A in chronic stroke.

Method

An analysis of long-term outcomes from national, multicenter, Phase III randomised trial with concealed allocation, blinded measurement and intention-to-treat analysis was carried out. Participants were 140 stroke survivors who were scheduled to receive botulinum toxin-A in any muscle(s) that cross the wrist because of moderate to severe spasticity after a stroke greater than 3 months ago, who had completed formal rehabilitation and had no significant cognitive impairment. Experimental group received botulinum toxin-A plus 3 months of evidence-based movement training while the control group received botulinum toxin-A plus a handout of exercises. Primary outcomes were goal attainment (Goal Attainment Scale) and upper limb activity (Box and Block Test) at 12 months (ie, 9 months beyond the intervention). Secondary outcomes were spasticity, range of motion, strength, pain, burden of care, and health-related quality of life.

Results

By 12 months, the experimental group scored the same as the control group on the Goal Attainment Scale (MD 0 T-score, 95% CI -5 to 5) and on the Box and Block Test (MD 0.01 blocks/s, 95% CI -0.01 to 0.03). There were no differences between groups on any secondary outcome.

Conclusion

Additional intensive upper limb rehabilitation following botulinum toxin-A in chronic stroke survivors with a disabled upper limb is not more effective in the long-term.

Trial Registration

ACTRN12615000616572 (12/06/2015).

Similar content being viewed by others

Backgroud

Stroke represents a huge burden on the health care system. A meta-analysis has shown that botulinum toxin-A injections reduce spasticity compared to placebo [1], but that this reduction in spasticity does not carry over to an improvement in the ability to perform everyday activities [2, 3]. After formal rehabilitation ceases, it is common for people with persistent spasticity due to their stroke to attend a ‘Spasticity Clinic’ where they may receive an injection of botulinum toxin-A in the upper limb, particularly into muscles of the forearm and hand [4, 5]. Thereafter, post-injection intervention varies widely due to a lack of evidence, with around a third of Australian clinics only providing handouts or advice to encourage motor training [5] in the absence of supervised therapy. Therefore, we designed an intensive upper limb rehabilitation program based on evidence-based guidelines for stroke that was to be provided post-injection. The three-month program – InTENSE – included 2 weeks of serial casting aimed at decreasing any contracture [6] that was then followed by 10 weeks of movement training, aimed at decreasing weakness [7] and improving movement [8, 9]. The program was designed to be patient driven; it was mostly carried out at home supported by phone calls, home visits and occasional attendance at the clinic. We then conducted a Phase III randomised trial to determine the clinical effect of additional upper limb rehabilitation following botulinum toxin-A [10]. The findings suggested that, in stroke survivors attending a spasticity clinic who were scheduled to receive botulinum toxin-A to a muscle crossing the wrist, an additional 3 months of evidence-based movement training was no more effective than botulinum toxin-A plus usual care in terms of goal attainment and upper limb activity. We concluded that in chronic, severely disabled stroke survivors, it is not worthwhile spending resources on providing anything more than usual care after botulinum toxin-A. This paper presents the long-term outcomes of this Phase III clinical trial in order to see if anything had changed.

Method

Design

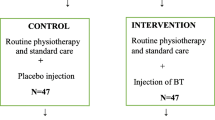

An analysis of the long-term (12 month) outcomes of the InTENSE trial was performed. The InTENSE trial was a national, multicentre, Phase III randomised trial with concealed allocation, blinded measurement and intention-to-treat analysis [11]. Stroke survivors were recruited from seven spasticity clinics across three states in Australia. Participants were randomly allocated to receive botulinum toxin-A plus evidence-based movement training or botulinum toxin-A plus usual care. Randomization was computer-generated, independent and concealed. For each clinic, allocation occurred in random permuted blocks so that after every block (of 4–8 participants), the experimental and control group contained equal numbers. Randomization occurred after injection of botulinum toxin-A. The schedule was stored off-site and group allocation was revealed online. Outcomes were measured at baseline, 3 months (end of intervention) and 12 months (9 months beyond the intervention). Measurements were collected at the clinic by researchers blind to group allocation; it was not possible to blind participants or therapists to group allocation. Data analyses were conducted by researchers blind to group allocation.

Patients, therapists, clinics

Patients were included if they were adults over 3 months post-stroke; were scheduled to receive a botulinum toxin-A injection to a muscle(s) that crosses the wrist (in accordance with the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme); and were not currently receiving upper limb rehabilitation [11]. They were excluded if they had had botulinum toxin-A injections and/or casting in the past 6 months; had contraindications to botulinum toxin-A injections; had other non-stroke related upper limb conditions (e.g., fracture, frozen shoulder, arthritis); had impaired cognition (≥ 5 errors on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire); or were unable to attend clinic ≥ 1/wk [11].

Intervention

After a standard injection program according to Australian practice recommendations [12] to a muscle(s) crossing the wrist, participants in the experimental group received the InTENSE program (see TIDIER checklist [10]). This program consisted of 2 weeks of serial casting in maximum wrist extension followed by 10 weeks of movement training aimed at decreasing weakness [6] and improving active movement [8, 9] and participants were encouraged to practice for 60 min per day, 7 days a week during the 10 weeks. Participants in the control group received a handout plus one follow-up telephone call to encourage independent practice. The handout was non-individualised and contained 7 stretches, and 8 arm and hand exercises. After the 3-month period of the intervention, there was no further intervention but any botulinum toxin-A injections were recorded.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes were goal attainment measured using the Goal Attainment Scale [13, 14] and reported as a T-score, and upper limb activity measured using the Box and Block Test [15] and reported as blocks/s.

Secondary outcomes were spasticity, wrist extension range of motion, grip strength, pain, burden of care and quality of life. Spasticity was measured using the Tardieu Scale and reported as a score 0–4, where 0 is no spasticity [16]. Passive range of wrist extension was measured using torque-controlled goniometry and reported in degrees [17]. Grip strength was measured as a maximum voluntary contraction using a Jamar dynamometer and reported as kg [18]. Pain was measured using a visual analogue scale and reported in cm from 0–10, where 0 is no pain. Burden of care was measured using the Carer Burden Scale and reported as a score 0–16, where 0 is no burden [19]. Health-related quality of life was measured using the EuroQol-5D [20] where overall health has a value between 0 and 100, where 0 is poor health.

Statistical analyses

Sample size was calculated to detect a between-group difference of 7 points on the Goal Attainment Scale T-score and 0.12 blocks/s on the Box and Block test with 80% power at a two-tailed significance level of 0.05. The calculation was based on the mean scores and standard deviations of the sample studied in our pilot trial [21]. On the basis of 10% attrition by 12 months, we planned to recruit a total of 136 participants, 68 per group.

An intention-to-treat analysis was conducted. Outcomes were analysed controlling for baseline values, and presented as mean between-group differences (95% CI).

Results

Flow of participants through the trial

140 people with stroke were recruited to the study from 03/07/2015 to 27/06/2018. Participants in both the experimental and control groups were similar in terms of their age, sex, level of education, previous living arrangements as well as chronicity, side of hemiplegia, cognition, sensation and neglect (Table 1).

The flow of participants through the trial is shown in Fig. 1. By Month 12, 7 participants (5%) were lost to follow-up – four from the experimental group and three from the control group. Therefore, 95% of the primary outcome – goal attainment – was collected. In addition, there was some missing data so that 93% of the other primary outcome – upper limb activity – was collected.

Compliance with trial method

During the intervention period, both the experimental and control group spent time each day practicing motor tasks to improve their upper limb activity. The control group did about half of the amount of practice as the experimental group both at the beginning of the intervention (28 vs 52 min/day) and at the end (20 vs 37 min/day). After the cessation of intervention, 35 (25%) participants went on to have at least one more injection of botulinum toxin-A to a muscle crossing the wrist.

Long-term effect of intervention between experimental and control groups

Group data for the two measurement occasions, within-group differences and between-group differences are presented in Table 2 for all outcome measures. In terms of goal attainment, by 12 months the experimental group scored the same (MD 0 T-score, 95% CI -5 to 5) as the control group on the Goal Attainment Scale. In terms of upper limb activity, the experimental group moved blocks at the same speed (MD 0.01 blocks/s, 95% CI -0.01 to 0.03) as the control group on the Box and Block Test. There was no difference between groups in any secondary measure. No trial-related adverse events were recorded.

Post-hoc analysis of long-term effect of intervention on all participants

When the experimental and control groups were combined into one group (Table 3), by 12 months there was a trend towards improvement in upper limb activity (MD 0.01 blocks/s, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.02), and a statistically significant improvement in spasticity (MD -0.4 out of 4, 95% CI -0.7 to -0.2), contracture (MD -10 deg, 95% CI -15 to -5), pain (MD -0.8 out of 10, 95% CI -1.2 to -0.3), and burden of care (MD -2.3 out of 16, 95% CI -3.1 to -1.4).

Post-hoc analysis of long-term effect of intervention between groups who did or did not receive further botulinum toxin-A

35 (25%) participants received a mean of 1.2 further botulinum toxin-A injection sessions beyond the intervention. By 12 months, they trended towards worse goal attainment (MD -5 T-score, 95% CI -10 to 1), had worse grip strength (MD -1.5 kg, 95% CI -3.0 to 0.0), but more range of motion (MD 14 deg, 95% CI 3 to 25) than those that did not receive further botulinum toxin-A (Table 4). There was no statistically significant difference between these groups in any other measure, including spasticity.

Discussion

This randomised trial found that, in chronic stroke survivors attending a spasticity clinic who received botulinum toxin-A to a muscle crossing the wrist, an additional 3 months of evidence-based movement training was no more effective in the long-term than botulinum toxin-A plus a handout of exercises in terms of goal attainment and upper limb activity. When the experimental and control groups were combined, overall, there were small improvements in spasticity, contracture, pain, and burden of care. When the cohort was divided according to further botulinum toxin-A injections, those that received further botulinum toxin-A had worse grip strength but better range of motion than those that did not receive it.

In terms of the effect of the intervention as an adjunct to botulinum toxin-A, immediately after the intervention at 3 months, there was no effect on any outcome except grip strength but this effect had disappeared by 12 months so that there was no between-group difference on any outcome. The lack of effect at 12 months is not surprising in light of the lack of effect at 3 months. In addition, the participants in this trial were representative of stroke survivors attending spasticity clinics in Australia in that they were chronic and severely disabled [10] and therefore may have had a limited potential for recovery [22]. There have been 3 systematic reviews of adjunct interventions for botulinum toxin-A published recently [2, 23, 24] but none have performed a meta-analysis and none of the randomized trials included in the reviews were published after our trial began. Our trial adds to the evidence that casting increases range of motion in the short-term [25] but that movement training does not enhance the effect of botulinum toxin-A in terms of activity.

When the cohort was considered together, immediately after the intervention at 3 months and beyond the intervention at 12 months, there was a half-point reduction in spasticity, small improvements in grip strength, pain and burden of care but no changes in upper limb activity or quality of life. However, at 3 months there was an increase in range of motion (8 deg) but this had changed to a decrease (10 deg) at 12 months. This is in line with two recent systematic reviews with meta-analyses investigating botulinum toxin-A after stroke [26, 27] which both found robust evidence for a decrease in spasticity and burden of care but no increase in upper limb activity, either in the short- [26, 27] or long-term [26]. Importantly, the review by Andringa [26] claims that the evidence is robust enough not to need further trials investigating the efficacy of botulinum toxin-A, but that fully powered trials of adjunct interventions are still needed.

The decrease in range of motion at the wrist from 3 to 12 months led us to perform a post-hoc analysis differentiating those who received further botulinum toxin-A injections from those that did not. On average, 25% of stroke survivors received further botulinum toxin-A over 1.1 sessions. At 12 months, while there was no difference in spasticity between these groups, those who received further botulinum toxin-A did demonstrate increased range of wrist extension but weaker muscle strength. This is in line with an observational study of multiple injections of botulinum toxin-A [28] which concluded that multiple injections of botulinum toxin formulation may be more effective in increasing range of motion than a single injection. Taken together these findings suggest that botulinum toxin-A needs to be ongoing to be of any benefit. However, further research is required to understand whether the improvement in range of motion is sufficient to balance out the potential reduction in grip strength.

This trial has both strengths and weaknesses. Its main strength was that it was fully powered; the confidence intervals for both the BBT and GAS did not cross any worthwhile effect. Its main weakness was that the participants, while representative of those attending spasticity clinics around Australia, were some 3 years after their stroke and very disabled [10], which means that they may not have been able to make improvements in upper limb activity. Also, there were missing data for the spasticity measure at 12 months, however, the missing data was random and the 12-month findings in line with the 3-month findings. Only a small number of participants continued botulinum toxin therapy after the 3-month assessment (25%), therefore we acknowledge that future clinical trials may provide more robust data regarding the effects of repeat injections.

Measurement of goal attainment using GAS may be considered both a strength and limitation. Using GAS offered an effective method for assessing changes in specific functional domains pertaining to upper limb motor training from the participant’s perspective of what was valued. These data are, however, based on participant report. Obtaining consumer reflections of the perceived impact of the InTENSE therapy program was critical, and while a strength, it should be acknowledged that these data are unblinded. To address this potential bias, the goal interviews were completed by an assessor blind to group allocation and interpreted alongside the blinded assessment of motor function (BBT).

The Australian, Canadian, and UK guidelines [29,30,31] all recommend that the use of botulinum toxin-A for spasticity management should be combined with concurrent rehabilitation. However, this recommendation is based on expert opinion rather than evidence. Our fully powered clinical trial taken together with recent evidence suggests clinicians who use botulinum toxin-A to manage spasticity in chronic, disabled patients can expect an improvement in secondary impairments but should not expect an improvement at the activity level even with training and can only expect improvements to last long-term if botulinum toxin-A is ongoing.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cardoso E, Rodrigues B, Lucena R, de Oliveira IR, Pedreira G, Melo A. Botulinum Toxin Type A for the Treatment of the Upper Limb Spasticity After Stroke. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005;63:30–3.

Mills PB, Finlayson H, Sudol M, O’Connor R. Systematic review of adjunct therapies to improve outcomes following botulinum toxin injection for treatment of limb spasticity. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(6):537–48.

Kinnear BZ, Lannin NA, Cusick A, Harvey LA, Rawicki B. Rehabilitation therapies after botulinum toxin-A injection to manage limb spasticity: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2014;94(11):1569–81.

Kwakkel G, Kollen B. Predicting improvement in the upper paretic limb after stroke: a longitudinal prospective study. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2007;25(5–6):453–60.

Cusick A, Lannin, N.A., Kinnear, B. Upper limb spasticity management for patients who have received Botulinum Toxin A injection: Australian therapy practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2014.

Scott H, Lannin NA, English C, Ada L, Levy T, Hart R, Crotty M. Addition of botulinum toxin type A to casting may improve wrist extension in people with chronic stroke and spasticity: A pilot double-blind randomized trial. Edorium J Disabil Rehabil. 2017;3:30–5.

Ada L, Dorsch S, Canning CG. Strengthening interventions increase strength and improve activity after stroke: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52(4):241–8.

Shaw L, Rodgers H, Price C, van Wijck F, Shackley P, Steen N, et al. BoTULS: a multicentre randomised controlled trial to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treating upper limb spasticity due to stroke with botulinum toxin type A. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(26):1–113, iii-iv.

Harris JE, Eng JJ, Miller WC, Dawson AS. A self-administered Graded Repetitive Arm Supplementary Program (GRASP) improves arm function during inpatient stroke rehabilitation: a multi-site randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2123–8.

Lannin NA, Ada L, English C, Ratcliffe J, Faux S, Palit M, Gonzalez S, Olver J, Cameron I. Effect of additional rehabilitation after botulinum toxin-A on upper limb activity in chronic stroke: the InTENSE trial. Stroke. 2020;51:556–62.

Lannin NA, Ada L, English C, Ratcliffe J, Crotty M. Effect of adding intensive upper limb rehabilitation to botulinum toxin-A on upper limb activity after stroke: protocol for the InTENSE trial. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(6):648–53.

Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. Position statement on the therapeutic use of botulinum toxin in rehabilitation medicine for spasticity and dystonia. Sydney: Australia; 2013.

Kiresuk TJ, Smith A, Cardillo JE. Goal Attainment Scaling: Applications, Theory, and Measurement: Taylor & Francis; 2014.

Turner-Stokes L, Baguley IJ, De Graaff S, Katrak P, Davies L, McCrory P, Hughes A. Goal attainment scaling in the evaluation of treatment of upper limb spasticity with botulinum toxin. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(1):81–9.

Mathiowetz V, Volland G, Kashman N, Weber K. Adult norms for the Box and Block Test of manual dexterity. Am J Occup Ther. 1985;39(6):386–91.

Patrick E, Ada L. The Tardieu Scale differentiates contracture from spasticity whereas the Ashworth Scale is confounded by it. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:173–82.

Ada L, Herbert R. Measurement of joint range of motion. Aust J Physiother. 1988;34:260–2.

Boissy P, Bourbonnais D, Carlotti MM, Gravel D, Arsenault BA. Maximal grip force in chronic stroke subjects and its relationship to global upper extremity function. Clin Rehabil. 1999;13(4):354–62.

Bhakta BB. Management of spasticity in stroke. Br Med Bull. 2000;56(2):476–85.

Golicki D, Niewada M, Karlinska A, et al. Comparing responsiveness of the EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L and EQ VAS in stroke patients. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(6):1555–63.

Lannin NA, Ada L, Levy T, English C, Ratcliffe J, Sindhusake D, Crotty M. Intensive therapy after botulinum toxin in adults with spasticity after stroke versus botulinum toxin alone or therapy alone: a feasibility randomised trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4:82.

Stinear CM, Byblow WD, Ackerley SJ, Smith MC, Borges VM, Barber PA. PREP2: A biomarker-based algorithm for predicting upper limb function after stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4(11):811–20.

Intiso D, Santamato A, Di Rienzo F. Effect of electrical stimulation as an adjunct to botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of adult spasticity: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:2123–33.

Picelli A, Santamato A, Chemell E, Cinone N, Cisari C, Gandolfi M, Ranieri M, Smania N, Baricich A. Adjuvant treatments associated with botulinum toxin injection for managing spasticity: An overview of the literature. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2019;62:291–6.

Farina S, Migliorini C, Gandolfi M, Bertolasi L, Casarotto M, Manganotti P. Combined effects of botulinum toxin and casting treatments on lower limb spasticity after stroke. Funct Neurol. 2008;23:87–91.

Andringa A, van de Port I, van Wegen E, Ket J, Meskers C, Kwakkel G. Effectiveness of Botulinum Toxin Treatment for Upper Limb Spasticity Poststroke Over Different ICF Domains: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:1703–25.

Sun L-C, Chen R, Fu C, Chen Y, Wu Q, Chen R-P, LinX-J, Luo S. Efficacy and Safety of Botulinum Toxin Type A for Limb Spasticity after Stroke: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Biomed Res Int. 2019;8329306

Ro T, Ota T, Saito T, Oikawa O. Spasticity and Range of Motion Over Time in Stroke Patients Who Received Multiple-Dose Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2020;29:104481.

Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for stroke management. Melbourne: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2017.

Teasell R, Foley N, Salter K, Bhogal S, Jutai J, Speechley M. Evidence-Based Review of Stroke 12th edition Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16(6):463–88.

Royal College of Physicians, British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine, The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Neurology and the Royal College of Occupational Therapists. Spasticity in adults: management using botulinum toxin. National guidelines. London: RCP, 2018.

Acknowledgements

InTENSE Trial Group: Natasha A. Lannin (Monash University, Alfred Health and La Trobe University), Julie Ratcliffe (Flinders University), Louise Ada (The University of Sydney), Coralie English (University of Newcastle), Maria Crotty (Flinders University), Ian D Cameron (The University of Sydney), Steven G. Faux (St Vincent's Health Australia), Mithu Palit (Alfred Health), John Olver (Monash University and Epworth Healthcare), Malcolm Bowman (St Vincent's Health Australia), Senen Gonzalez (Austin Health), Emma Schneider (Alfred Health), Rachel Milte (Flinders University), Angela Vratsistas-Curto (St Vincent's Health Australia), Annabel McNamara (Flinders University), Christine Shiner (University of New South Wales and St Vincent's Health Australia), Elizabeth Lynch (Flinders University), Louise Beaumont (Alfred Health), Maggie Killington (Flinders University and Central Adelaide Local Health Network), Megan Coulter (Alfred Health), Doungkamol Sindhusake (University of Sydney), Brian Anthonisz (Alfred Health), Hong Mei Khor (Flinders Medical Centre), Justin Tan (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Kwong Teo (Alfred Health), Lily Ng (Alfred Health), Lydia Huang (Flinders Medical Centre), Maria Paul (Hampstead Rehabilitation Centre), Neil Simon (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Nidhi Gupta (Westmead Hospital), Rebecca Martens (Westmead Hospital), Sam Bolitho (St Vincent's Health Australia), Shea Morrison (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Sue Hooper (Hampstead Rehabilitation Centre), Yan Chow (Alfred Health), Yuriko Watanabe (St Vincent's Health Australia), Adrian Cowling (Flinders Medical Centre), Clara Fu (Flinders Medical Centre), Emily Toma (Flinders Medical Centre), Genevieve Hendrey (Alfred Health), Jacinta Sheehan (La Trobe University), Josh Butler (Hampstead Rehabilitation Centre), Judith Hocking (Flinders University), Lauren Rutzou (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Megan White (Alfred Health), Michael Snigg (Central Adelaide Local Health Network), Rhiannon Hughes (Flinders Medical Centre), Sarah Sweeney (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Sophie Flint (Central Adelaide Local Health Network), Tamina Levy (Flinders University and Flinders Medical Centre), Val Bramah (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Cameron Lathlean (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Carrie McCallum (Alfred Health), Elaine Chui (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Frances Allan (Hills Medical Service), Heather Webber (Flinders Medical Centre), Jo Campbell (St Vincent's Health Network Sydney), Julie Lawson (Flinders University), Karen Borschmann (Florey Neurosciences), Katelyn Moloney (Alfred Health), Laura Jolliffe (Monash University), Lisa Cameron (Alfred Health), Owen Howlett (Bendigo Health), Rebecca Nicks (Eastern Health and Alfred Health), and Sophie O’Keefe (Monash University).

Funding

The study was supported by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; GNT1079542); NAL is supported by National Heart Foundation of Australia (GNT102055).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NL and MC conceived the study; NL, LA and JR designed the analysis; NL, LA, CE, JR, MC designed the study and procured funding; MC, SF, MP, SG, JO were site principal investigators and oversaw site recruitment and site data collection; ES was the national trial coordinator; IC oversaw data safety and monitoring; NL, LA and IC performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript; all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental protocol was established, according to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Alfred Health Human Research Ethics Committee on 11 December 2014, reference number 442/12. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants and/or their legal guardian(s) before data collection began. The study was registered in ACTRN on 12 June 2015, reference number ACTRN12615000616572.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

J Olver and S Gonzalez declare that they have received honoraria from Allergan; J Olver, M Palit and S Gonzalez declare that they have received honoraria from Ipsen; S Gonzalez declares that he has received honoraria from Merz. The other authors report no conflicts.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lannin, N.A., Ada, L., English, C. et al. Long-term effect of additional rehabilitation following botulinum toxin-A on upper limb activity in chronic stroke: the InTENSE randomised trial. BMC Neurol 22, 154 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02672-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02672-8