Abstract

Background

Progressive haemorrhagic injury after surgery in patients with traumatic brain injury often results in poor patient outcomes. This study aimed to develop and validate a practical predictive tool that can reliably estimate the risk of postoperative progressive haemorrhagic injury (PHI) in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Methods

Data from 645 patients who underwent surgery for TBI between March 2018 and December 2020 were collected. The outcome was postoperative intracranial PHI, which was assessed on postoperative computed tomography. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression model, univariate analysis, and Delphi method were applied to select the most relevant prognostic predictors. We combined conventional coagulation test (CCT) data, thromboelastography (TEG) variables, and several predictors to develop a predictive model using binary logistic regression and then presented the results as a nomogram. The predictive performance of the model was assessed with calibration and discrimination. Internal validation was assessed.

Results

The signature, which consisted of 11 selected features, was significantly associated with intracranial PHI (p < 0.05, for both primary and validation cohorts). Predictors in the prediction nomogram included age, S-pressure, D-pressure, pulse, temperature, reaction time, PLT, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, FIB, and kinetics values. The model showed good discrimination, with an area under the curve of 0.8694 (95% CI, 0.8083–0.9304), and good calibration.

Conclusion

This model is based on a nomogram incorporating CCT and TEG variables, which can be conveniently derived at hospital admission. It allows determination of this individual risk for postoperative intracranial PHI and will facilitate a timely intervention to improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nearly 50 million people worldwide suffer from traumatic brain injury (TBI) each year [1]. According to a study by the Global Burden of Disease, the prevalence of TBI increased by 8.4% between 1990 and 2016 [2].C,oagulopathy is a common complication of TBI and is associated with an increased morbidity and mortality [3]; it has an estimated incidence of 7–63% [4, 5]. Coagulopathy is often the main cause of postoperative progressive haemorrhagic injury (PHI) [6, 7]. For patients who have undergone surgery after TBI, intracranial PHI often leads to increased intracranial pressure and cerebral herniation, further threatening the patients’ lives. Studies have shown that the mortality rate of patients with PHI is nine times higher that of patients without PHI [8]. The incidence of PHI in patients with craniocerebral trauma is approximately 23% [9, 10].

Predicting the outcome of this condition is challenging because of the complex mechanism of coagulopathy and the lack of uniform diagnostic and evaluation criteria. Routine laboratory indicators for clinical detection of coagulopathy mainly include prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), international normalised ratio (INR), and platelet count, jointly called conventional coagulation test (CCT) findings. Although widely used, CCTs have several limitations. First, the determination of platelet count and fibrinogen can only reflect quantity, not function. Second, PT, APTT, and INR can reflect the disturbance of a single pathway but cannot be used to assess the complex interaction between multiple pathways and the overall coagulation function [11].Many hospitals also use thromboelastography (TEG) for the clinical detection of coagulation diseases; the measures used in TEG include reaction time (R), kinetics time (K), α angle, maximum amplitude (MA), percent lysis 30 min after MA, and coagulation index. As a measure of clot strength, TEG does not rely on biochemical pathways affecting coagulation [12]. Windelov et al. showed that TEG was more effective than CCT in predicting poor prognosis in patients with craniocerebral trauma [13]. Other studies have shown that TEG can provide information on coagulation function faster than CCT can, thus enabling timely correction of coagulation dysfunction in patients with craniocerebral trauma [14, 15].

Therefore, CCT together with TEG can effectively reflect the quantity and quality of coagulation factors and platelets, reflect the speed and intensity of clot formation, and, thus, reflect the overall coagulation function. A clinical prediction model based on CCT and TEG could enable clinicians to intuitively understand the coagulation function of patients with craniocerebral trauma, provide a basis for component blood transfusion, reduce occurrence of postoperative PHI, and improve the prognosis of patients. To this end, we developed and validated a clinical prediction model to support the management of postoperative coagulopathy in patients with TBI.

Methods

Patients

We collected the clinical medical records and imaging data of 645 TBI patients admitted to the Department of Neurosurgery, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University from March 2018 to December 2020 who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) a clear history of head trauma, (2) age ≥ 18 years, (3) hospital admission within 72 h after injury, and (4) need for surgical treatment. The exclusion criteria were: (1) use of antiplatelet (such as aspirin and clopidogrel) or anticoagulant drugs (such as warfarin); (2) severe multiple organ failure; (3) associated hematologic system diseases; (4) hemodynamic instability during admission to the intensive care unit (heart rate < 50 beats/min or systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or mean arterial pressure < 65 mmHg); (5) severe multiple injuries (ISS ≥ 25 points); (6) previous central nervous system diseases (such as stroke and brain tumour); (7) pregnancy; and (8) incomplete clinical data.

Data extraction

The clinical data, including demographic characteristics, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score upon admission, pupil diameter, light reflex, and postoperative CCTs and TEG findings, were extracted from the hospital’s case management system.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the R software (version 4.0.3; https://www.Rproject.org). Demographic data of the patients were evaluated by T test and X2 test. For continuous variables, t-test is used for comparison, and for categorical variables, X2 test is used. The reported statistical significance levels were all two-sided, with statistical significance set at 0.05.

Outcome measures

All patients underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan within 6 h postoperatively to determine if there was any bleeding in the surgical area. Subsequently, CT scans were performed from 6 h after surgery to the time of discharge as needed to determine whether PHI had occurred.

Our outcome was postoperative intracranial PHI, which was defined as a intracranial haemorrhage on any subsequent postoperative computed tomography (CT) scan that was not seen in the initial scan or the amount of bleeding in the original site was 25% higher than that in the previous CT scan [16, 17]. We divided the patients into two groups according to the above criteria, namely PHI group and non-PHI group.

Predictor variables

We screened several features from 16 candidate predictors (i.e. age, gender, S-pressure, D-pressure, pulse, temperature, GCS score, R, K, αangel, MA, PLT, PT, APTT, FIB), which were consistently associated with the outcome of PHI, using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) binary logistic regression model, univariate analysis, and the Delphi method for inclusion in the prediction models [18]. We log transformed values for continuous variables, such as temperature and K.

Model development

The association between predictor variables and outcomes was analysed using logistic regression models. Prognostic strength was quantified as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In order to facilitate clinical application, we established a nomogram based on binary logic analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were drawn to evaluate the predictive value of the model.

Model performance

An ROC curve was plotted using R software, and the ability of the model to discriminate between patients with PHI and without PHI was assessed using an area under the receiver operator characteristics (AUC) curve analysis. A perfect model would have an AUC of 1.

Model validation

Internal validation evaluates the stability of a prediction model against random changes in sample composition. Due to limitation of samples, external validation is not appropriate in our study. Internal validation was performed using the bootstrap resampling technique, where regression models were fitted in 100 bootstrap replicates drawn with replacement from the development sample. The model was refitted in each bootstrap replicate and tested on the original sample to estimate optimism in model performance.

All methods were performed in accordance with the TRIPOD statement published in 2015 [19].

Results

Clinical characteristics

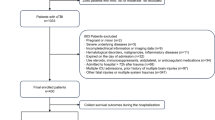

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. We collected data of 645 patients treated in the Neurosurgical intensive care unit of Xiangya Hospital. A total of 153 patients and 247 patients were excluded because of lack of TEG, PT, APTT tests data information, respectively. One patient was excluded because outcome data was not available (Fig. 1). In total, 203 patients did not suffer intracranial PHI after surgery, but it was observed in 41 patients. There was no statistical difference in the distributions of age, sex, D-pressure, pulse, temperature, GCS score, R value, K value, angle, and MA between the two groups (PHI group and non-PHI group). S-pressure (p = 0.04), PLT (p < 0.001), APTT (p < 0.001), and FIB (p = 0.003) were significantly associated with postoperative intracranial PHI.

Feature selection

In total, 16 candidate features were extracted from TEG and CCT variables. Of these, 11 potential predictors were selected on the basis of 244 patients in the cohort (Fig. 2). The predictors were selected by the LASSO logistic regression model were non-zero coefficients (Fig. 3). Based on the advice of experienced professor of neurosurgeries and researchers at our institution, 16 variables were evaluated using the Delphi method; from these, the most relevant clinical predictors were selected.

Feature selection using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) binary logistic regression model. A Tuning parameter (λ) selection in the LASSO model using 10-fold cross-validation via minimum criteria. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUC) curve was plotted against log (λ). Vertical lines were drawn at the optimal values using the minimum criteria and one standard error of the minimum criteria (the 1-SE criteria). A value of 0.004 with log (λ) of − 5.324 was chosen (1-SE criteria) according to the 10-fold cross-validation. B LASSO coefficient profiles of 16 texture features. A coefficient profile plot was plotted against the log (λ) sequence. Using 10-fold cross-validation, the optimal λ resulted in 11 non-zero coefficients

Based on the univariate analysis, Delphi method and Lasso technique results, 11 final predictors were identified: age, S-pressure, D-pressure, pulse, temperature, R, PLT, PT, APTT, FIB and K value (Table 2).

Model development

A model incorporating age, S-pressure, D-pressure, pulse, temperature, R, PLT, PT, APTT, FIB, and K value was developed and presented as a nomogram (Fig. 4).

Performance assessment

Good discrimination (Fig. 5A) and good calibration (Fig. 5B) were observed in the validation set. The AUC of the nomogram was 0.8694 (95% CI, 0.8083–0.9304), and since it was > 0.75, it was considered to have excellent discrimination. In addition, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test also produced a nonsignificant p-value of 0.7233, which can prove the same thing [20].

A Receiver operating characteristic curves of the nomogram. B Calibration curves of the nomogram. Illustration of the agreement between the predicted risk of postoperative intracranial PHI(progressive haemorrhagic injury) and the observed outcomes of postoperative PHI in patients with traumatic brain injury

Clinical usefulness of the model

The decision curve analysis (DCA) constructed by our data provided a net benefit over the “treat-all” or “treat-none” strategy at a high-risk threshold probability > 2.0% (Fig. 6), which show that the model is clinically useful. For instance, with a high-risk threshold probability of 40%, use of the model could provide an added net benefit of 0.268 compared to the “treat-all” or “treat-none” strategy.

Discussion

To our knowledge, various of predictive models have been used to help clinician to evaluate the outcome of TBI patients [21]. However, this is the first study to develop and internally validate a tool to predict postoperative intracranial PHI in patients with TBI using CCTTEG-based clinically relevant predictors.

By intuitively predicting the risk of postoperative coagulation dysfunction in patients with TBI, this predictive model can identify patients with poor prognosis at early stages and allows timely clinical intervention, thus improving patient prognosis. We empirically define patient who gets a score in our model over 0.5 as high risk man and effective measures should been taken to prevent the intracranial PHI after surgery.

Our predictive model predicted the risk of postoperative intracranial PHI in TBI, which can facilitate early clinical interventions. There are two main measures to been taken to intervene the disorder of blood coagulation. The first one is component blood transfusion, including fresh frozen plasma, prothrombin complex concentrate, concentrated blood platelets, fibrinogen and reprogramming factors VII, which could supply the absence materials of blood and address the severe coagulopathy [22]. Another way is drug intervention. Many studies have suggested that TXA, desmopressin and other drugs can be used to improve coagulation dysfunction in patients with TBI [23, 24].

This study had some limitations. First, as till date, not enough TBI cases have been tested by TEG at our institution, there was no external validation of the model to examine its portability and generalizability. External validation can preclude the possibility of overfitting during modelling [25]. Therefore, a multicentre prospective clinical trial to validate or optimise this predictive model is warranted. Second, the retrospective nature of the study limited access to clinical data such as Abbreviated Injury Scale and illness severity scoring findings, which are used to comprehensively assess the severity of multiple injuries in the body that have an impact on the severity craniocerebral trauma. Third, the TBI patients included in this study were only treated with trepanation and drainage, which meant that patients with complex TBI requiring craniectomy were missing from this sample. Therefore, clinical data related to these patients were not included among the predictive variables in this study, which may limit the application of this model to complex TBI. Fourth, our conclusion is different with some published studies results that K-value and alpha angle were significant predictors,which is associated with severity of TBI [26, 27]. Finally, in this study, preoperative data on coagulation function status of patients were lacking and most of the patients underwent TEG only once after surgery, which may have led to individual differences having a negative impact on the development of our model.

Conclusion

Our prediction model included a developmental set of 244 patients and achieved good performance in internal validation. As the predictor items, which have been previously identified as powerful prognostic indicators, in this prediction model are readily available at hospital admission, our model has potential for timely intervention.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APTT:

-

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- CCT:

-

Conventional coagulation test

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- INR:

-

International normalised ratio

- K:

-

Kinetics time

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- MA:

-

Maximum amplitude

- PHI:

-

Progressive haemorrhagic injury

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- R:

-

Reaction time

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

- TEG:

-

Thromboelastography

- PLT:

-

Platelets

- FIB:

-

Fibrinogen

- ISS:

-

Injury severity score

References

Maas AIR, Menon DK, Adelson PD, et al. Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(12):987–1048. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30371-x [published Online First: 2017/11/11].

Collaborators GN. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30499-x published Online First: 2019/03/19.

de Oliveira Manoel AL, Neto AC, Veigas PV, et al. Traumatic brain injury associated coagulopathy. Neurocrit Care. 2015;22(1):34–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-014-0026-4 published Online First: 2014/07/24.

Epstein DS, Mitra B, Cameron PA, et al. Acute traumatic coagulopathy in the setting of isolated traumatic brain injury: definition, incidence and outcomes. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29(1):118–22. https://doi.org/10.3109/02688697.2014.950632 published Online First: 2014/08/26.

Shrestha A, Joshi RM, Devkota UP. Contributing factors for coagulopathy in traumatic brain injury. Asian J Neurosurg. 2017;12(4):648–52. https://doi.org/10.4103/ajns.AJNS_192_14 published Online First: 2017/11/09.

Stein SC, Young GS, Talucci RC, et al. Delayed brain injury after head trauma: significance of coagulopathy. Neurosurgery. 1992;30(2):160–5. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-199202000-00002 published Online First: 1992/02/01.

Allard CB, Scarpelini S, Rhind SG, et al. Abnormal coagulation tests are associated with progression of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2009;67(5):959–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181ad5d37 published Online First: 2009/11/11.

Schnüriger B, Inaba K, Abdelsayed GA, et al. The impact of platelets on the progression of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2010;68(4):881–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d3cc58 published Online First: 2010/04/14.

Yuan F, Ding J, Chen H, et al. Predicting progressive hemorrhagic injury after traumatic brain injury: derivation and validation of a risk score based on admission characteristics. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(12):2137–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2011.2233 published Online First: 2012/05/10.

Cepeda S, Gómez PA, Castaño-Leon AM, et al. Traumatic Intracerebral hemorrhage: risk factors associated with progression. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(16):1246–53. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2014.3808 published Online First: 2015/03/11.

Haas T, Fries D, Tanaka KA, et al. Usefulness of standard plasma coagulation tests in the management of perioperative coagulopathic bleeding: is there any evidence? Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(2):217–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu303 published Online First: 2014/09/11.

Rugeri L, Levrat A, David JS, et al. Diagnosis of early coagulation abnormalities in trauma patients by rotation thrombelastography. J Thrombos Haemostas. 2007;5(2):289–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02319.x published Online First: 2006/11/18.

Windeløv NA, Welling KL, Ostrowski SR, et al. The prognostic value of thrombelastography in identifying neurosurgical patients with worse prognosis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolys. 2011;22(5):416–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MBC.0b013e3283464f53 published Online First: 2011/04/07.

Cotton BA, Faz G, Hatch QM, et al. Rapid thrombelastography delivers real-time results that predict transfusion within 1 hour of admission. J Trauma. 2011;71(2):407–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e31821e1bf0 [published Online First: 2011/08/10]. discussion 14–7.

Davenport R, Manson J, De'Ath H, et al. Functional definition and characterization of acute traumatic coagulopathy. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(12):2652–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182281af5 published Online First: 2011/07/19.

Liu J, Tian HL. Relationship between trauma-induced coagulopathy and progressive hemorrhagic injury in patients with traumatic brain injury. Chin J Traumatol= Zhonghua chuang shang za zhi. 2016;19(3):172–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.01.011 published Online First: 2016/06/21.

Oertel M, Kelly DF, McArthur D, et al. Progressive hemorrhage after head trauma: predictors and consequences of the evolving injury. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(1):109–16. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2002.96.1.0109 published Online First: 2002/01/17.

McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):655–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x published Online First: 2016/02/06.

Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;350:g7594. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7594 published Online First: 2015/01/09.

Alba AC, Agoritsas T, Walsh M, et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: Users' guides to the medical literature. Jama. 2017;318(14):1377–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.12126 published Online First: 2017/10/20.

Anderson TN, Hwang J, Munar M, et al. Blood-based biomarkers for prediction of intracranial hemorrhage and outcome in patients with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(1):80–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000002706 published Online First: 2020/04/07.

Zhang LM, Li R, Sun WB, et al. Low-dose, early fresh frozen plasma transfusion therapy after severe trauma brain injury: a clinical, prospective, randomized, controlled study. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:e21–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.024 published Online First: 2019/09/16.

Yutthakasemsunt S, Kittiwatanagul W, Piyavechvirat P, et al. Tranexamic acid for patients with traumatic brain injury: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Emerg Med. 2013;13:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-227x-13-20 published Online First: 2013/11/26.

Naidech AM, Maas MB, Levasseur-Franklin KE, et al. Desmopressin improves platelet activity in acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2451–3. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.114.006061 published Online First: 2014/07/10.

Bleeker SE, Moll HA, Steyerberg EW, et al. External validation is necessary in prediction research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(9):826–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00207-5 published Online First: 2003/09/25.

Webb AJ, Brown CS, Naylor RM, et al. Thromboelastography is a marker for clinically significant progressive hemorrhagic injury in severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-021-01217-0 published Online First: 2021/04/14.

Harhangi BS, Kompanje EJ, Leebeek FW, et al. Coagulation disorders after traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir. 2008;150(2):165–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-007-1475-8 discussion 75. [published Online First: 2008/01/02].

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients whose anonymised data were used for this research.

Funding

This project was supported by the Xiangya Medical Big Data Foundation, the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (Grant No.2018JJ2649), and Health and Family Planning Commission of Hunan Province (Grant No. B2019191).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TC and SC are the co-first authors of the work. TC contributed to the study design, data collection, analysis of data, writing, literature search, and revision of the work. SC contributed to the study design, interpretation of data, writing, and literature search. YC, LW and YW contribute to the acquisition of data and revision of the work. JL contributed to the study design, collection and interpretation of data, and critical revision. TC, SC, YC, LW, YW and JL contributed to the approval of the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital Central South University. The data are anonymous, and the requirement for informed consent was therefore waived by Medical Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital Central South University. All methods were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests or personal financial interests to declare. They have no personal relations with organizations, publishers or any individual that may jeopardize the integrity of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, T., Chen, S., Wu, Y. et al. A predictive model for postoperative progressive haemorrhagic injury in traumatic brain injuries. BMC Neurol 22, 16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02541-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02541-w