Abstract

Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) complexity poses challenges for individuals with Parkinson’s, providers, and researchers. A recent multisite randomized trial of a proactive, telephone-based, nurse-led care management intervention - Care Coordination for Health Promotion and Activities in Parkinson’s Disease (CHAPS) - demonstrated improved PD care quality. Implementation details and supportive stakeholder feedback were subsequently published. To inform decisions on dissemination, CHAPS Model components require evaluations of their fidelity to the Chronic Care Model and to their implementation. Additionally, assessment is needed on whether CHAPS addresses care challenges cited in recent literature.

Methods

These analyses are based on data from a subset of 140 intervention arm participants and other CHAPS data. To examine CHAPS Model fidelity, we identified CHAPS components corresponding to the Chronic Care Model’s six essential elements. To assess implementation fidelity of these components, we examined data corresponding to Hasson’s modified implementation fidelity framework. Finally, we identified challenges cited in current Parkinson’s care management literature, grouped these into themes using open card sorting techniques, and examined CHAPS data for evidence that CHAPS met these challenges.

Results

All Chronic Care Model essential elements were addressed by 17 CHAPS components, thus achieving CHAPS Model fidelity. CHAPS implementation fidelity was demonstrated by adherence to content, frequency, and duration with partial fidelity to telephone encounter frequency. We identified potential fidelity moderators for all six of Hasson’s moderator types. Through card sorting, four Parkinson’s care management challenge themes emerged: unmet needs and suggestions for providers (by patient and/or care partner), patient characteristics needing consideration, and standardizing models for Parkinson’s care management. CHAPS activities and stakeholder perceptions addressed all these themes.

Conclusions

CHAPS, a supportive nurse-led proactive Parkinson’s care management program, improved care quality and is designed to be reproducible and supportive to clinicians. Findings indicated CHAPS Model fidelity occurred to the Chronic Care Model and fidelity to implementation of the CHAPS components was demonstrated. Current Parkinson’s care management challenges were met through CHAPS activities. Thus, dissemination of CHAPS merits consideration by those responsible for implementing changes in clinical practice and reaching people in need.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT01532986, registered on January 13, 2012.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The complexity of health care delivery in Parkinson’s disease (PD)Footnote 1 poses challenges for individuals with Parkinson’s, providers, and researchers; thus, health service and implementation researchers are examining new Parkinson’s care models to address gaps in care and delivery system problems [1, 2]. These include multi-component interventions involving many disciplines addressing patients’ needs while supporting providers [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. For example, prevention and treatment of fall risks/falls is a priority concern for patients with enduring (chronic) conditions like Parkinson’s [14], requiring communication, collaboration, and coordination among patients, care partners, and health care team members. Specific responsibilities require: (1) identifying fall risks/falls as a problem (by physicians and nurses), (2) considering medication changes (by physicians), (3) assessing and managing unsafe behaviors (by mental health and care team), (4) assessing ways to make daily activities safer (by patients, care partners, nurses, physical and occupational therapists), and (5) providing care partner education and support (by nurses, occupational and physical therapists, and social services).

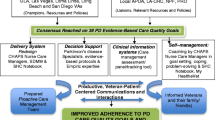

Our new Parkinson’s care model is the proactive nurse-led telephone-based care management intervention, Care Coordination for Health Promotion and Activities in Parkinson’s Disease (CHAPS). CHAPS evolved from prior health services research on a dementia care management program, Alzheimer’s Disease Coordinated Care for San Diego Seniors (ACCESS), that was based on the Chronic Care Model [15], a widely used framework with strategies to facilitate productive, patient-centered communications and interactions for providing high quality chronic disease care. The Chronic Care Model is comprised of six essential elements: (1) health system resources and policies, (2) community resources and policies, (3) delivery system redesign, (4) decision support, (5) clinical information systems, and (6) self-management support. ACCESS achieved higher care quality on 21 of 23 (p < 0.013 for all) dementia guideline recommendations [16]. For CHAPS, health services researchers designed the CHAPS intervention with input from direct-care nurses and providers to meet a set of 38 PD quality indicators.

To choose the set of indicators, the researchers pulled 106 PD indicators and guidelines from multiple sources: Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE), the American Academy of Neurology, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, European Federation of Neurological Societies, and the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Centers (PADRECC) Quality Indicator Project [EMC, KIC, BGV, PD Rating Booklet 2009, unpublished]. Then a Task Force of Parkinson’s disease specialists, nurse educators, representatives from community organizations committed to Parkinson’s, and a nurse working in a movement disorder clinic rated these 106 indicators and guidelines on validity and their room for improvement. The result was a set of 38 indicators used to guide the design of the CHAPS intervention [7]. CHAPS was then implemented and compared to usual care in a randomized controlled trial, by measuring adherence to 18 indicators, of the 38, that were likely sensitive to care management.

Parent study

In brief, we conducted the CHAPS trial between 2012 and 2017 at five Veterans Health Administration medical centers in the Southwest United States. Patient/participants were community-dwelling men and women who had been in the United States military (i.e., veterans) in the care of one of the five sites and were the unit of randomization. Potential participants had at least 2 International Classification of Disease − 9 (ICD 9) diagnostic codes over 12 months prior to the study and were not already enrolled in an existing care management program (e.g., congestive heart failure, diabetes). Of note, these study participants had more disability compared to another community-based population (Health Utilities Index 3 mean 0.46 versus 0.61) [17].

The intervention commenced with the CHAPS Initial Assessment tool administered by the CHAPS nurse care manager. The Assessment’s embedded algorithms identified 31 standard problems/topics. A 3-ringed binder, the Siebens Health Care Notebook (Notebook), a self-care, communication, and navigational tool, was personalized by the CHAPS nurse care manager and mailed to each participant [18]. This Notebook was a single location to keep an individual’s health care information. This included (1) a sheet with the nurse care manager’s photograph and contact information (telephone number and mailing address), (2) an updated medication list, (3) personalized next steps in “My Action Plan”, (4) tailored education sheets, and (5) a copy of the individual’s CHAPS Assessment to show other providers. Nurse care managers scheduled a specific time to teach Notebook use and included care partners at participants’ request. Nurse care managers also provided routine follow-up calls to coach participants on problems/topics identified - guided by problem/topic-specific intervention protocols - at 6 months, at annual reassessment, and at 18 months [7]. Interim follow-up calls occurred as needed. The Siebens Domain Management Model™ (I Medical/Surgical Issues, II Mental Status/Emotions/Coping, III Physical Function, and IV Living Environment) served as CHAPS’ person/patient-centered Organizing Framework to guide and document holistic care [14, 19].

Decision support occurred through the problem/topic-specific intervention protocols, huddles between the CHAPS nurse care managers and Parkinson’s disease specialists, and through meetings among the nurse care managers. These nurse care managers interacted with other health care professionals (e.g., primary care providers and medical specialists, social workers, speech language pathologists, physical and occupational therapists) through routine medical record documentation and warm hand-offs (e.g., in person, by telephone, by secure email, and/or co-signature requests of medical record notes).

The CHAPS intervention improved care quality through increased adherence to the 18 PD quality of care indicators [17] relative to usual care. We subsequently published details of the CHAPS implementation [14] and the overall positive feedback provided by stakeholders (CHAPS nurse care managers, Parkinson’s disease specialists, and patients/participants) [20].

The first goal of the study reported here is to evaluate the fidelity of the CHAPS Model to the Chronic Care Model as this establishes six essential model elements have, in fact, been applied in the new CHAPS intervention. The second goal is to evaluate fidelity to implementation of the CHAPS components. Examining implementation fidelity contributes towards understanding an intervention and whether its components were operating as intended. This then increases reproducibility, confidence in attributing outcomes to these components, and potential for dissemination [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Several published frameworks for measuring fidelity vary slightly in scope and detail [23] yet have common core concepts of adherence and potential moderators [21, 22]. Because CHAPS was designed in 2011, the third goal of this study was to identify recently published challenges in Parkinson’s care management from 2012 to 2020 and assess if these challenges were addressed in the CHAPS implementation.

Methods

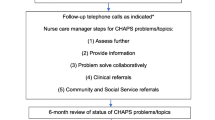

Aims of this descriptive study were to evaluate: (1) fidelity of the CHAPS Model to the Chronic Care Model’s six elements (i.e., were model components created for each element) [7, 15]; (2) fidelity of CHAPS Model implementation (i.e., were components used and protocols followed (adherence)); (3) evaluation of potential fidelity implementation moderators; and (4) if and how CHAPS addressed challenges in Parkinson’s care management cited recently in the literature. Implementation fidelity was based on the modified conceptual framework by Hasson [21] (Fig. 1).

The modified conceptual framework for implementation fidelity (originally from Carroll et al). Legend: Fig. 1 is from Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. BioMed Central Implementation Science 2010;5: 67, page 3

Setting and eligible participants

Participant recruitment in the CHAPS trial [17] was from a total of 452 candidates identified on chart review. The final number of trial participants was 328 (73% of the 452). A total of 166 were randomly assigned to usual care (control) and 162 to the CHAPS intervention [17]. The intervention subgroup for this fidelity study was 140 participants that received at minimum the CHAPS Initial Assessment administered by the CHAPS nurse care manager [14]. This subgroup had a mean age of 69.4 years (standard deviation (SD) 10.3 years), was 95% male, and had a mean Health Utilities Index 3 of 0.45 (SD 0.31) (range: − 0.36 (worst) to 1 (best)), a patient-reported outcome assessment of health-related quality of life [27]. These values did not differ significantly from the 22 intervention participants who did not receive CHAPS nurse care management for various reasons [14]. A total of 52% (n = 73/140) of the intervention subgroup received care from providers both within and outside the Veterans Affairs Medical Centers [14].

Data

To assess fidelity to the Chronic Care Model [15], CHAPS’ theoretical model, two researchers (KIC, HCS) created a table of the Chronic Care Model’s six essential elements designed to encourage high quality care (Table 1). CHAPS Model components that corresponded to these elements were added to the table [7, 14]. To assess implementation fidelity to these CHAPS components, findings from a prior CHAPS publication [14] were reviewed for examples of adherence variables (Fig. 1) and entered in the table. Next, the six fidelity potential moderator types from Hasson’s model (Fig. 1) [21] were entered into another table (Table 2). Examples for these six types were identified from published CHAPS data [14, 17, 20], quantified where feasible, and added to the table. An additional data source was the Principal Investigator (nurse researcher, KIC) performing on site observation of care delivery and having discussions with CHAPS nurse care managers.

A literature review of research articles published between 2012 and 2020 using search terms Parkinson’s disease, patient-centered care, and care coordination yielded articles enumerating challenges in Parkinson’s care delivery and research [6, 9,10,11,12,13, 28, 29]. Challenges likely to be addressed through nurse-led care management were identified.

Analyses

Open card sorting methodology was used to organize Parkinson’s care challenges identified in the literature. Two researchers (KIC, HCS) together examined care challenges for word similarities (generalizations in semantics, analogies, and metaphors). They sorted these challenges into groups that were not pre-specified [30, 31]. They used their knowledge of healthcare and language to refine the sorts. For items on which they disagreed, they came to a collaborative decision for placement in a group. These groups were given names and all data (themes and associated items) were entered into a table (Table 3). Then these researchers examined CHAPS nurse care manager activities [14] and stakeholder perception survey responses [20] for examples addressing each challenge item and these were added to Table 3.

Results

Fidelity to the chronic care model

Table 1 lists CHAPS components, in column 2, for each of the six Chronic Care Model elements; thus, the CHAPS Model achieved fidelity to this theoretical model. For the elements of Delivery System Redesign, Decision Support, and Self-management Support, there were multiple components for supporting CHAPS nurse care managers, Parkinson’s disease specialists, and participants.

Fidelity to CHAPS implementation

Adherence

CHAPS Model components, listed in Table 1, were implemented as demonstrated by content, frequency, and duration results (column 3 of Table 1), achieving full implementation fidelity for all components except for partial fidelity to telephone encounter frequency. Adherence coverage, as defined by the Hasson model, was the proportion of a target group that received the intervention [21]. For CHAPS, this was defined post-hoc as, at minimum, receipt of the CHAPS Initial Assessment. Adherence coverage was 86% (n = 140 of the 162 intervention arm participants).

Potential moderators

Potential moderators during the CHAPS implementation were identified (Table 2) for each of the six conceptional framework categories [21] (Fig. 1). First, concerning participant responsiveness, survey results at study end indicated engagement by all three stakeholder groups (i.e., patient/participants, CHAPS nurse care managers, and Parkinson’s disease specialists). Their feedback was overall positive [20]. CHAPS nurse care manager usability responses included facilitators for both the Siebens Domain Management Model and the Notebook and the three attributes: user-friendly, person/patient-centered, and organized. Second, comprehensiveness of policy (protocol) description consisted of already published data describing the study protocol [7] and details of the CHAPS implementation [14]. Third, strategies to facilitate implementation included educational materials, practice with CHAPS tools, and scheduled communications for decision support. Fourth, quality of delivery modes included multiple care management components for proactive holistic Parkinson’s care and nurse care managers’ attention to participants’ self-care actions [14]. Fifth, recruitment and maintaining participant involvement was effective [14]. Sixth, some aspects of the CHAPS implementation’s context provided support for the randomized controlled trial while other aspects were barriers to full implementation. For example, a hiring freeze resulted in CHAPS nurse care manager availability for only 68% median CHAPS nurse care manager days of coverage, interquartile range, 47–100% [17].

Control group

In examining implementation fidelity, Hasson recommended a description of the control group. In the CHAPS parent study, both intervention and control (usual care) groups had access to Veterans Affairs PADRECCs present at all five sites to provide medical, educational, and support services to patients with movement disorders [39]. All participants received a brief educational handout on Parkinson’s [40] and had similar numbers of patient/participant interactions by visit and provider types from baseline to 18 months [17].

The control group (usual care) received no CHAPS Initial Assessments. Of note, they were assessed significantly less frequently for excessive daytime sleepiness (14% vs 85%, p < 0.0001) and orthostatic hypotension (41% vs 86%, p < 0.0001), psychosis/hallucinations/delirium (60% vs 94%, p < 0.0001), cognition (70% vs 93%, p < 0.0001), depression (80% vs 94%, p = 0.0002), and falls (74% vs 96%, p < 0.0001) [17]. These participants did not receive the CHAPS self-care Notebook and they received significantly fewer telephone calls (0.11 SD 0.2 versus 3.02 SD 2.2).

Parkinson’s care challenges from the literature and the CHAPS implementation

Four themes emerged for grouping related Parkinson’s care challenges through open card sorting after three iterations: (1) Unmet Needs Identified by Patient and/or Care Partner (six items) [28, 32,33,34,35], (2) Suggestions for Providers Identified by Patient and/or Care Partner (four items) [10, 28, 32, 34], (3) Patient Characteristics Needing Consideration (two items) [6, 33, 36, 37], and (4) Standardizing Models for Parkinson’s Care Management (three items) [6, 9,10,11,12,13, 29, 38] (Table 3). These challenges were addressed in the CHAPS implementation through a defined CHAPS nurse care manager role and standardized CHAPS components. These nurse care managers tailored activities using problem/topic intervention protocol steps: (1) assess further, (2) provide information, (3) problem solve collaboratively, (4) clinical referrals, and (5) community and social services referrals [7, 14]. We also identified examples of stakeholder perceptions related to the challenges (Table 3) [20].

Discussion

The CHAPS Model and its multiple components reflected all six essential elements of the Chronic Care Model, thus achieving fidelity to this model. The CHAPS Model components were delivered as intended, thus achieving full implementation fidelity. This was demonstrated by adherence to content, frequency, and duration except for partial fidelity to telephone encounter frequency. We identified potential fidelity moderators for all six of Hasson’s moderator types. Stakeholders’ (participants, CHAPS nurse care managers, Parkinson’s disease specialists) responsiveness indicated CHAPS relevancy to patient care. Additionally, the CHAPS implementation addressed recently cited challenges in Parkinson’s care management.

Limitations

The subgroup studied (n = 140) was mostly male, all veterans, and they were receiving care within the Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. These characteristics may limit generalizability of findings in future implementations. However, over half of the participants received care from other health systems like other individuals with Parkinson’s who are receiving care from multiple sources. The literature abstraction of challenges in Parkinson’s care was not exhaustive and additional challenges may be identified by others.

The association of CHAPS components to the clinical outcome of fewer depressive symptoms on a depression screener [17] was not analyzed as is recommended for evaluating fidelity (Fig. 1). The importance of this type of analysis was demonstrated in the ACCESS study when one of many activities, a home assessment, was associated with improved caregiver mastery at 18 months [41]. Future CHAPS implementations could assess component and clinical outcome relationships.

Implications

Simplification of care delivery

Given the complexity of Parkinson’s care, a strength of CHAPS is the simplification of care delivery through discrete, defined, and transparent structured components for reproduceable dissemination. Quality of delivery was evidenced by meeting PD quality of care indicators and garnering positive stakeholder feedback.

Organized and relevant documentation

The 4-domain Siebens Domain Management Model, as the Organizing Framework, applied in documentation, allows clinicians to find information about areas of greatest concern. For example, if pneumonia prevention is a concern for Parkinson’s disease specialists or primary care providers, they can review Domain I to learn about a patient’s swallowing status. If psychiatrists are concerned about hallucinations or delirium, they can focus on acute medical issues in Domain I that could be contributory to cognitive issues documented under Domain II. Any provider with concerns about function (Domain III) or the home situation (Domain IV) can quickly review these sections.

The CHAPS structured documentation by CHAPS nurse care managers may initially appear as a documentation burden, a known contributor to clinician burnout [38]; however, these nurse care managers obtained and documented information that both they and Parkinson’s disease specialists appreciated and found relevant [20]. For example, motor and non-motor signs and symptoms were assessed, and managed, significantly more frequently than in the usual care group [17]. The process of assessing Parkinson’s disease signs and symptoms - per the PD quality indicators - are not clinical or patient-reported outcomes [38], yet we believe they are necessary precursors to managing these problems if participants’ outcomes are to be improved.

Comparisons with nursing roles in other Parkinson’s models of care

CHAPS addresses nursing assessments, care coordination, and care management similar to published information on the Dutch nursing guidelines in ParkinsonNet [14, 42, 43] and the Integrated Parkinson’s Care Network [44, 45]. All three programs utilize nurses with specialized knowledge in Parkinson’s and address self-management support needs of individuals with Parkinson’s. All have a network approach. CHAPS was administered in one of 6 regional Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence for Parkinson’s disease, called PADRECCs, in the United States with building blocks for networked care [46]. The PADRECCs expanded care of Parkinson’s through a national Veterans Affairs consortium of providers with movement disorder expertise.

ParkinsonNet proposes 1:370 full-time employee equivalent (FTEE) nurse to individual with Parkinson’s with additional help from a care coordinator, not necessarily a nurse [42]. CHAPS achieved a ratio of 1:125 FTEE nurse care manager to individuals with Parkinson’s without any coordinator assistance. CHAPS contact time and frequency [17] are like those proposed for ParkinsonNet nurses [43].

To the best of our knowledge, the proactive CHAPS intervention is the first to document improved Parkinson’s care quality through nurse care managers oriented to Parkinson’s using a set of specific tools. These tools included (1) a standardized CHAPS Assessment regardless of disease stage, with algorithms to trigger problems/topics and their severity for care management, (2) an evidence-based, interdisciplinary person/patient-centered Organizing Framework (the Siebens Domain Management Model), (3) 5-step problem/topic intervention protocols for decision support for nurse care managers, (4) a personalized self-care plan, “My Action Plan”, with coaching by the CHAPS nurse care managers, and (5) an individualized self-care Notebook with teaching in its use. The overall contact frequency approach was flexible with contacts every 6 months and more frequently if needed.

Contributing insights to care management of enduring health conditions

CHAPS, as a care management program, includes communication, collaboration, and coordination like other successful non-Parkinson’s care delivery studies. The Advanced Illness Coordinated Care Program [47] provided health counseling, education, and care coordination in a 6-session intervention focused on individuals’ disease status and long-term planning. This intervention was based on a 3-domain biopsychosocial model. However, CHAPS used the 4-domain Siebens Domain Management Model [19], including function, which is consistent with the biopsycho-ecological model. CHAPS nurse care managers assessed participants’ understanding of their Parkinson’s and planning for future needs (e.g., discussion about surrogate decision-maker, which occurred more frequently than in usual care group [17]). In collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illness [48], nurses received decision-support from physicians, worked collaboratively with them, and followed guideline-based protocols, as occurred similarly in CHAPS. In the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration [49], six activities were identified across four programs that reduced hospitalizations in high-risk patients. These activities occurred in CHAPS through nurse care managers who: (1) were a single point of contact, (2) met regularly with Parkinson’s disease specialists, (3) delivered evidence-based education to patients, (4) provided tailored medication management, and (5) addressed transitional care (e.g., medication review, discharge instructions) via telephone. Finally, (6) in-person meetings to supplement telephone calls were used a few times in CHAPS (n = 23 (3.5%) of 656 notes) [14]. Given these care management components common to prior studies and CHAPS, health systems and providers may wish to examine their Parkinson’s care management delivery and determine if they can use the CHAPS Model, and its components, building on their current strengths.

Importance of stakeholder feedback in research

The Care and Learn model for improving care quality in health care delivery highlights the importance of people involved (patients and clinicians) and a holistic approach to patients and their context. The model advocates for gaining evidence about the caring provided and on stakeholder learning including program acceptability [50]. CHAPS followed these considerations. The caring provided was described in detail using documentation review [14]. The focus on individuals is reflected in the CHAPS stakeholder feedback. Patients reported helpfulness of the CHAPS nurse care manager, acceptability of the CHAPS Initial Assessment, overall knowledge about Parkinson’s disease care, and Notebook benefits and features liked. CHAPS nurse care manager and Parkinson’s disease specialist surveys addressed knowledge/understanding, self-confidence, clinical appropriateness, participant’s self-management improvement, and program endorsement. Overall, these surveys provided positive feedback and some suggestions for refinements. Additionally, surveys on usability of new tools (i.e., Siebens Domain Management Model, CHAPS Assessment, and Siebens Health Care Notebook) provided evidence of their acceptability [20].

Telehealth

The literature supports providing Parkinson’s care remotely (telehealth via telephone and/or home video or clinical video telehealth) in both rural and urban areas. Telehealth is advantageous when access to specialists is limited, patients have trouble keeping appointments, specialists have inadequate time per patient, and coronavirus disease (COVID 19) precludes some in-person visits [51,52,53,54,55]. These findings add support to CHAPS as a telephone-based program. In the future, CHAPS could be augmented with clinical video telehealth when clarity in assessment or face-to-face teaching are needed. Other telehealth applications could include zoom/virtual classes for individuals’ education and support (e.g., introductory class to the self-care Notebook tool) by CHAPS nurse care managers organized by support staff. Future digital technologies like wearable sensors (e.g., detection of sleep disturbances, on/off phenomena) and their data could also be integrated into proactive CHAPS care management [56].

Safety

Among the multiple dimensions of safety [57, 58], CHAPS addressed four directly: care integration, patient engagement, meaningful work for providers, and broader interdisciplinary approaches [59,60,61]. First, care integration started with CHAPS nurse care managers proactively identifying participants’ safety risks through a structured CHAPS Assessment with embedded algorithms. Assessment Summary reports were shared through electronic medical record documentation, available to inpatient and outpatient Veterans Affairs providers, and through paper copies in participants’ personalized Notebooks. Structured team communications were designed for care integration through collaboration and coordination (e.g., clinical huddles, orderly documentation format/template using the Siebens Domain Management Model). The self-care Notebook served as a care integration tool, portable to any venue (inpatient, outpatient, residential), especially important for urgent care and emergencies [62]. Second, CHAPS fostered patient/participant engagement through nurse care manager coaching in specific actions and, at times, including the care partner (e.g., when to call Parkinson’s disease specialist, using electronic and/or hard copy self-care tools based on participants’ preferences [14, 20, 63, 64]). Third, the CHAPS Program facilitated meaningful work for the nurse care managers and Parkinson’s disease specialists (e.g., CHAPS Assessment provided information that would improve their patient care, their patients had a better understanding of how to manage their Parkinson’s). Furthermore, nurse care managers and Parkinson’s disease specialists endorsed CHAPS (81% would refer other patients to CHAPS) [20]. Fourth, broad interdisciplinary approaches occurred in CHAPS through referrals (n = 501) to providers, Veterans Affairs services, and community services. Warm hand-offs (n = 358) between nurse care managers and other health care professionals occurred frequently through live telephone discussions, concurrent co-signatures on specific notes, secure email, and face-to-face discussions [14].

Conclusion

CHAPS, a supportive nurse-led proactive Parkinson’s care management program, improved care quality and is designed to be reproducible and supportive to clinicians. Findings indicated CHAPS Model fidelity occurred to the Chronic Care Model and to implementation of the CHAPS components. Current Parkinson’s care management challenges were met through CHAPS activities. Thus, dissemination of CHAPS merits consideration by those responsible for implementing changes in clinical practice and reaching people in need.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as, by the time we deidentify data to the degree acceptable, too many key variables are taken out given that veterans can be re-identified with enough social and/or personal demographic and area information. Additionally, the small pool of intervention nurse care managers and Parkinson’s disease specialists would potentially allow tracing qualitative survey data back to them. The data that support the findings of this study are from the Veterans Affairs, USA; thus, restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data are however available upon reasonable request from and with permission from the Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy, Veterans Affairs, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Notes

Terminology is evolving for the name “Parkinson’s disease”. We refer to it as Parkinson’s, de-emphasizing the “disease” label in this paper except when it is a proper name in a title, as in Care Coordination and Health Activities in Parkinson’s Disease (CHAPS), the original intervention’s title and in referring to Parkinson’s disease specialists. As CHAPS is disseminated after this implementation, its title will be Care Management and Health Activities in Parkinson’s as care coordination is only one component of the comprehensive care management provided by this intervention.

Abbreviations

- CHAPS:

-

Care Coordination for Health Promotion and Activities in Parkinson’s Disease

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- ACCESS:

-

Alzheimer’s Disease Coordinated Care for San Diego Seniors

- ACOVE:

-

Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders

- PADRECC:

-

Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Centers

- ICD 9:

-

International Classification of Disease − 9

- Notebook:

-

Siebens Health Care Notebook

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- FTEE:

-

Full-time employee equivalent

- COVID 19:

-

Coronavirus disease

- VA HSR&D-NRI:

-

Veteran Affairs Health Services Research and Development – Nursing Research Initiative

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Cheng EM, Siderowf A, Swarztrauber K, Eisa M, Lee M, Vickrey BG. Development of quality of care indicators for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disorders. 2004;19:136–50.

Cheng EM, Swarztrauber K, Siderowf AD, Eisa MS, Lee M, Vassar S, et al. Association of specialist involvement and quality of care for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disorders. 2007;22:515–22.

Prizer LP, Browner N. The integrative care of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. J Parkinsons Dis. 2012;2:79–86.

Parashos SA. Challenges of multidisciplinary care in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;2013(10):932–3.

van der Marck MA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, Overeem S, Munneke M, Guttman M. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Mov Disorders. 2013;26:605–11.

van der Marck BBR. How to organize multispecialty care for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20S1:S167–S173.

Connor K, Cheng E, Siebens HC, Lee ML, Mittman BS, Ganz DA, et al. Study protocol of "CHAPS": a randomized controlled trial protocol of care coordination for health promotion and activities in Parkinson’s disease to improve the quality of care for individuals with Parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:258–67.

Gray BH, Sarnak DO, Tanke M. ParkinsonNet: an innovative Dutch approach to patient-centered care for a degenerative disease. Commonwealth Fund. 2016:1–11. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/case-study/2016/dec/parkinsonnet-innovative-dutch-approach-patient-centered-care. Posted Dec 23, 2016. Accessed 16 Nov 2021.

Bloem BR, Rompen L, deVries NM, Klink A, Munneke M, Jeurissen P. ParkinsonNet: a low-cost health care innovation with a systems approach from the Netherlands. Health Aff. 2017;36:1987–96.

Radder DLM, de Vries NM, Riksen NP, Diamond SJ, Gross D, Gold DR, et al. Multidisciplinary care for people with Parkinson’s disease: the new kids on the block! Expert Rev Neurotherapeutics. 2019;19:145–57.

Tenison E, Smink A, Redwood S, Darweesh S, Cottle H, van Halteren A, et al. Proactive and integrated management and empowerment in Parkinson’s disease: designing a new model of care. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020;8673087:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8673087 Posted March 30, 2020, Accessed January 5, 2021.

Prell T, Siebecker F, Lorrain M, Tönges L, Warnecke T, Klucken J, et al. Specialized staff for the care of people with Parkinson’s disease in Germany: an overview. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2581 (12 pages).

Rajan R, Brennan L, Bloem BR, Dahodwala N, Gardner J, Goldman JG, et al. Integrated care in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disorders. 2020;35:1509–31.

Connor KI, Siebens HC, Mittman BS, Ganz DA, Barry F, Ernst EJ, et al. Quality and extent of implementation of a nurse-led care management intervention: care coordination for health promotion and activities in Parkinson’s disease (CHAPS). BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:732–49.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–44.

Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, Pearson MO, Della Penna RD, Ganiats TG, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:713–26.

Connor KI, Cheng EM, Barry F, Siebens HC, Lee ML, Ganz DA, et al. Randomized trial of care management to improve Parkinson disease care quality. Neurology. 2019;92:e1831–42.

Siebens H (2008) Siebens Health Care Notebook Revised 2018. ISBN 978-164008829-0.

Siebens H. Proposing a practical clinical model. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18:60–5.

Connor KI, Siebens HC, Mittman BS, McNeese-Smith DK, Ganz DA, Barry F, et al. Stakeholder perceptions of components of a Parkinson disease care management intervention, care coordination for health promotion and activities in Parkinson’s disease (CHAPS). BMC Neurol. 2020;20:437–50.

Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci. 2010;5(67):9.

Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2(40):9.

Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350(h1258):14.

Morrison JD, Becker H, Stuifbergen AK. Evaluation of intervention fidelity in a multi-site clinical trial in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2017;49:344–8.

McGee D, Lorencatto F, Matvienko-Sikar K, Toomey E. Surveying knowledge, practice and attitudes towards intervention fidelity within trials of complex healthcare interventions. Trials. 2018;19(504):14.

Bragstad LK, Bronken BA, Sveen U, Hjelle EG, Kitzmüller G, Martinsen R, et al. Implementation fidelity in a complex intervention promoting psychsocial well-being following stroke: an explanatory sequential mixed methods study. BMC med research. Methodology. 2019;19(59):18.

Horsman J, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G. The health utilities index (HUI): concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:54.

van der Eijk M, Faber MJ, Ummels I, Aarts JWM, Munneke M, Bloem BR. Patient-centeredness in PD care: development and validation of a patient experience questionnaire. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:1011–6.

Radder DLM, Nonnekes J, van Minwegen M, Eggers C, Abbruzzese G, Alves G, et al. Recommendations for the Organization of Multidisciplinary Clinical Care Teams in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020:1087–98.

Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field. Methods. 2003;15:85–109.

Connor K, McNeese-Smith D, van Servellen G, Change B, Lee M, Cheng E, et al. Insight into dementia care management using social-behavioral theory and mixed methods. Nurs Res. 2009;58:348–58.

Hellqvist C, Berterö C. Support supplied by Parkinson’s disease specialist nurses to Parkinson’s disease patients and their spouses. App Nursing Res. 2015;28:86–91.

Plouvier AOA, Hartman TCO, van Litsenburg A, Bloem BR, van Weel C, Lagro-Janssen LM. Being in control of Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study of community-dwelling patients’ coping with changes in care. Euro J Gen Practice. 2018;24:138–45.

Vlaanderen FP, Rompen L, Munneke M, Stoffer M, Bloem BR, Faber MJ. The voice of the Parkinson customer. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019;9:197–201.

Zizzo N, Bell E, Lafontaine A. Examining chronic care patient preferences for involvement in health-care decision making: the case of Parkinson’s disease patients in a patient-centered clinic. Health Expect. 2017;20:655–64.

Chaudhuri KR, Rojo JM, Schapira AHV, Brooks DJ, Stocchi F, Odin P, et al. A proposal for a comprehensive grading of Parkinson’s disease severity combining motor and non-motor assessments: meeting an unmet need. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57221–8.

Titova N, Martinez-Martin P, Katunina E, Chaudhuri KR. Advanced Parkinson’s or “complex phase” Parkinson’s disease? Re-evaluation is needed. J Neural Transm. 2017;124:1529–37.

Calabresi P, Nitro P, Schwarz HB. A nurse-led model increases quality of care in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2019;92:1–2.

Pogoda TK, Cramer IE, Meterko M, Lin H, Hendricks A, Holloway RG, et al. Patient and organizational factors related to education and support use by veterans with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disorders. 2009;24:1916–24.

VA Healthcare. Healthwise for life: a self-care guide for veterans; 2011. p. 273.

Connor KI, Vickrey BG, Lee ML, Vassar SD. Determining care management activities associated with mastery and relationship strain for dementia caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:891–7.

Lennaerts H, Groot M, Rood B, Gilissen K, Tulp H, van Wense E, et al. A guideline for Parkinson’s disease nurse specialists, with recommendations for clinical practice. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7:749–54.

Radder DLM, Lennaerts HH, Vermeulen H, van Asseldonk T, Delnooz CSC, Hagen RH, et al. The cost-effectiveness of specialized nursing interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease: the NICE-PD study protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. Trials. 2020;21(88):11.

Kessler D, Hauteclocque J, Grimes D, Mestre T, Côté D, Liddy C. Development of the integrated Parkinson’s care network (IPCN): using co-design to plan collaborative care for people with Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1355–64.

Kessler D, Hatch S, Alexander L, Grimes D, Côté D, Liddy C, et al. The integrated Parkinson’s disease care network (IPCN): qualitative evaluation of a new approach to care for Parkinson’s disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104:136–42.

van de Warrenburg BP, Tiemessen M, Munneke M, Bloem BR. The architecture of contemporary care networks for rare movement disorders: leveraging the ParkinsonNet experience. Front Neurol. 2021;12(638853):8.

Engelhardt JB, Rizzo VM, Della Penna RD, Feigenbaum PA, Kirkland KA, Nicholson JS, et al. Effectiveness of care coordination and health counseling in advancing illness. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:817–25.

Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–20.

Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff. 2012;31:1156–66.

Montori VM, Hargraves I, McNeillis RJ, Ganiats TG, Genevro J, Miller T, et al. The care and learn model: a practice and research model for improving healthcare quality and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;34:154–8.

Venkataraman V, Donohue SJ, Biglan KM, Wicks P, Dorsey ER. Virtual visits for Parkinson disease – a case series. Neurol Clin Pract. 2014;4:146–52.

Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. NEJM. 2006;375:154–61.

Schreiber SS. Teleneurology for veterans in a major metropolitan area. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:698–701.

Cilia R, Bonvegna S, Straccia G, Andreasi NG, Elia AE, Romito LM, et al. Effects of COVID-19 on Parkinson’s disease clinical features: a community-based case-control study. Mov Disorders. 2020;35:1287–92.

Helmich RC, Bloem BR. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson’s disease: hidden sorrows and emerging opportunities. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10:351–4.

Espay AJ, Hausdorff JM, Sanchez-Ferro Á, Klucken J, Merola A, Bonato P, et al. A roadmap for implementation of patient-centered digital outcome measures in Parkinson’s disease obtained using mobile health technologies. Mov Disord. 2019;34:657–63.

Carayon P, Wooldridge A, Hose BZ, Salwei M, Benneyan J. Challenges and opportunities for improving patient safety through human factors and system engineering. Health Aff. 2018;37:1862–9.

Bates DW, Singh H. Two decades since to err is human: an assessment of progress and emerging priorities in patient safety. Health Aff. 2018;37:1736–43.

Leape L, Berwick D, Clancy C, Conway J, Gluck P, Guest J, et al. Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:424–8.

Macken L, Hyrkas K. Contemporary issues in nursing: patient safety, decision-making, and social support in challenging economic times. J Nurs Manage. 2013;21:987–8.

Patient Engagement Action Team. Engaging Patients in Patient Safety – a Canadian Guide. Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Last modified December 2019. 2017. http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/engagingpatients. Accessed 16 Nov 2021.

Rogers K. What you need to prepare for the COVID-19 surge this season. https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/27/health/how-to-prepare-for-covid-surge-wellness/index.html, Posted October 27, 2020, Accessed October 27, 2020.

Jabr F. Why the brain prefers paper. Sci Am. 2013;309:48–53.

Klucken J, Krüger R, Schmidt P, Bloem BR. Management of Parkinson’s disease 20 years from now: towards digital health pathways. J Parkinsons Dis. 2018;8(Suppl 1):S85–94.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Erik J. Ernst NP for assistance in intervention design, and Megan K Connor, Lisa K Edwards, and Michael G McGowan for prior data collection.

Funding

This work was funded by the Veteran Affairs Health Services Research and Development – Nursing Research Initiative (VA HSR&D-NRI) 11–126. Supplemental funding was received from the Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation Implementation and Policy, Veterans Affairs, Los Angeles, California, USA as a LIP funding supplement to VA HSR&D-NRI 11–126. Funders were not involved in designing the study; collecting, analyzing, or interpreting the data; or in writing or submitting the manuscript for publication. Where authors are identified as personnel of the Veterans Affairs, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the Veterans Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows: KIC and BSM conceived and designed the research. KIC and HCS conducted card sorting analyses. HCS, BSM, DAG, FB, DKM, EMC, and BGV provided advice on study design, analyses, and interpretation of results. KIC and HCS were responsible for drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Boards of the five participating Veterans Affairs Healthcare Systems (Greater Los Angeles, Long Beach, Loma Linda, and San Diego, California; and Las Vegas, Nevada) waived the requirement for documentation of written consent, allowed verbal consent for the participants (veterans), and gave permission for the study on November 9, 2011. The Clinical Trial Registration, NCT01532986, was listed on January 13, 2012. CHAPS nurse care managers and Parkinson’s disease specialists surveyed for their perceptions were not considered subjects per Veterans Health Administration Institutional Review Boards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests except Hilary C Siebens, MD who uses the 4-domain clinical organizing framework she designed, Siebens Domain Management Model™, in consulting work with health care organizations and others. Also, she is the author of the Siebens Health Care Notebook, a self-care tool.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Connor, K.I., Siebens, H.C., Mittman, B.S. et al. Implementation fidelity of a nurse-led RCT-tested complex intervention, care coordination for health promotion and activities in Parkinson’s disease (CHAPS) in meeting challenges in care management. BMC Neurol 22, 36 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02481-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02481-5