Abstract

Background

Cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) are small, rounded, dark-signal lesions on brain MRI that represent cerebral hemosiderin deposits resulting from prior microhemorrhages and are neuroimaging biomarkers of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Here, we report a case of innumerable CMBs in a patient with hepatic encephalopathy underlying decompensated liver cirrhosis.

Case presentation

An 83-year-old woman diagnosed with hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis 40 years before was referred to our neurology clinic for progressive disorientation of time and place, personality changes, and confusion with somnolence over 2 weeks. Based on the laboratory, neuroimaging, and electrophysiological findings, we diagnosed the patient with hepatic encephalopathy, and her symptoms recovered within 12 h after proper medical management. Brain MRI showed innumerable CMBs in the bilateral frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes. Since the distribution of CMBs in the patient was mainly corticosubcortical and predominantly in the posterior cortical regions, and the apolipoprotein E genotype was ε4/ε4, we speculated that CAA and hepatic encephalopathy coexisted in this patient.

Conclusions

We suggest that severe liver dysfunction associated with long-term decompensated liver cirrhosis may be related to an increased number of CMBs in the brain. Our findings indicate that decompensated liver cirrhosis may be a risk factor for the development of CMBs and corroborate a link between the liver and the brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) are small, rounded, dark-signal lesions on brain MRI that represent cerebral hemosiderin deposits that result from prior microhemorrhages and are neuroimaging biomarkers of cerebral small vessel disease, such as arteriosclerosis and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Growing evidence suggests that CMBs are associated with an increased risk of hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, cognitive decline, and dementia [1]. Recently, a few studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between the severity of chronic liver disease and the number of CMBs [2, 3]. We report a case of innumerable CMBs in a patient with hepatic encephalopathy underlying decompensated liver cirrhosis.

Case presentation

An 83-year-old woman was referred to the neurology clinic for progressive disorientation of time and place, personality changes such as apathy and irritability, and a confusion with somnolence over 2 weeks. Forty years earlier, the patient was diagnosed with hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis. After diagnosis, she was repeatedly hospitalized and managed for recurrent esophageal variceal bleeding, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy. The patient’s daughter reported that the patient had developed progressive memory decline over 2 years; however, cognitive decline was not evaluated because of changes in her medical condition. She also had a history of diabetes, dilated cardiomyopathy, and atrial fibrillation. No familial history of stroke or dementia was noted. On neurological examination, the cranial nerves were intact; she had normal movements of the extraocular muscles. Motor examination revealed normal muscle strength and tone; however, she had diminished deep tendon reflexes, bradykinesia, and hypomimia. The Babinski sign was not elicited, and the sensory examination results were normal. Hepatic encephalopathy was suspected, and a laboratory and imaging diagnostic workup was performed.

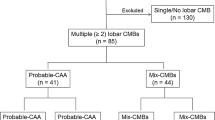

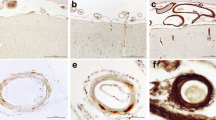

The results of laboratory tests were as follows: total bilirubin, 1.95 mg/dL (0.3 ~ 1.2 mg/dL); albumin, 2.2 d/dL (3.5 ~ 5.2 d/dL); PT INR, 2.25 (0.9 ~ 1.2); ammonia, 349 ug/dL (27 ~ 90 μg/dL). The patient’s kidney function was within the normal range, and she did not have proteinuria or albuminuria. There were no symptoms or signs of systemic amyloidosis. Brain MRI revealed bilateral symmetric high signal intensity at the globus pallidus and substantia nigra on T1-weighted images (Fig. 1). In addition, electroencephalography showed triphasic waves and bursts of intermittent rhythmic delta activity. Considering the laboratory, neuroimaging, and electrophysiological findings, we diagnosed the patient with hepatic encephalopathy grade 3 based on the West Haven criteria. Treatment with lactulose enema and intravenous hydration with branched-chain amino acids was immediately initiated, and her symptoms recovered within 12 h. The patient scored 22/30, after losing 1, 4, and 3 points on the temporal orientation, attention and calculation, and recall of three items tasks, respectively, in the Mini-Mental State Examination. However, we found innumerable CMBs in the bilateral frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes on the susceptibility-weighted imaging sequence (Fig. 2). Since the distribution of CMBs in the patient were mainly corticosubcortical (grey-white matter junction) and predominantly in the posterior cortical regions, with no family history suggesting hereditary CAA, and the apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype was ε4/ε4, we speculated that sporadic CAA and hepatic encephalopathy coexisted in this patient.

Discussion and conclusions

CAA is a cerebrovascular disease caused by the accumulation of β-amyloid in the tunica media and adventitia of cortical and leptomeningeal small vessels [1]. The clinical presentation of CAA includes spontaneous lobar intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), cognitive impairment and dementia, and transient focal neurological episodes. The only known genetic risk factors for sporadic CAA are APOE alleles, the ɛ4 allele for CAA, and the ɛ2 allele for CAA-related ICH and hematoma expansion [1]. Definite diagnosis of CAA can only be made after a postmortem pathologic examination of the brain. However, multiple lobar CMBs on brain MRI have been successfully validated as a diagnostic marker for CAA, and 90% of neuroimaging-diagnosed CAA patients had moderate to severe CAA on neuropathology [1].

The CMBs in the present case were uncountable, and this unique neuroimaging finding has never been reported. To the best of our knowledge, the observed number of CMBs was a distinct feature of this patient, being greater than that in typical CAA [4, 5]. We suggest that, along with the patient’s APOE genotype, severe liver dysfunction associated with long-term decompensated liver cirrhosis may be related to an increased number of CMBs in the brain. Previous studies demonstrated that chronic liver diseases are associated with endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and arterial stiffness in other organs, which are also related to the development of CMBs [2, 3]. In addition, we speculate that the severe liver dysfunction and underlying CAA in this case caused an increase in the number of CMBs through the breakdown of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), since increased BBB permeability is known to underlie hepatic encephalopathy [6]. However, we could not rule out the possibility that the patient’s impaired coagulation function contributed to the number of CMBs, since a greater variability in INR is associated with a higher prevalence of CMBs [7].

To our knowledge, this is the first neuroimaging report of a patient with innumerable CMBs and hepatic encephalopathy. Our findings indicate that decompensated liver cirrhosis may be a risk factor for the development of CMBs and corroborate a link between the liver and the brain. Further studies are needed to evaluate the pathophysiological mechanisms of CAA in patients with chronic liver disease.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- CMBs:

-

Cerebral microbleeds

- CAA:

-

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- APOE :

-

Apolipoprotein E

- ICH:

-

Intracranial hemorrhage

- BBB:

-

Blood–brain barrier

References

Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Gurol ME, Ayata C, Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP, Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM. Emerging concepts in sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain J Neurol. 2017;140(7):1829–50.

Kim YD, Song D, Heo JH, Kim SU, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Kim KJ, Han KH. Relationship between cerebral microbleeds and liver stiffness determined by transient elastography. PloS one. 2015;10(9):e0139227.

Jang H, Kang D, Chang Y, Kim Y, Lee JS, Kim KW, Jang YK, Kim HJ, Na DL, Shin HY, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cerebral small vessel disease in Korean cognitively normal individuals. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1814.

Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the elderly. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(6):871–80.

Greenberg SM, Nandigam RN, Delgado P, Betensky RA, Rosand J, Viswanathan A, Frosch MP, Smith EE. Microbleeds versus macrobleeds: evidence for distinct entities. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2382–6.

Ferenci P. Hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology Rep. 2017;5(2):138–47.

Akoudad S, Darweesh SK, Leening MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, Stricker BH, Ikram MA, Vernooij MW. Use of coumarin anticoagulants and cerebral microbleeds in the general population. Stroke. 2014;45(11):3436–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (NRF-2021R1C1C1012429). The role of the funding body was in collection and analysis of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CHO and JSL contributed to the conception, acquisition of data, drafting, and reporting of the case. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kyung Hee University Hospital. Written consent was obtained from the patient’s husband.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s husband for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Oh, C., Lee, J. Innumerable cerebral microbleeds in hepatitis B virus-related decompensated liver cirrhosis: a case report. BMC Neurol 21, 245 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02291-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02291-9