Abstract

Background

Alexander disease (AxD) is a rare neurological disease, especially in adults. It shows variable clinical and radiological features.

Case presentation

We diagnosed a female with AxD presenting with paroxysmal numbness of the limbs at the onset age of 28-year-old, progressing gradually to spastic paraparesis at age 30. One year later, she had ataxia, bulbar paralysis, bowel and bladder urgency. Her mother had a similar neurological symptoms and died within 2 years after onset (at the age of 47), and her maternal aunt also had similar but mild symptoms at the onset age of 54-year-old. Her brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed abnormal signals in periventricular white matter with severe atrophy in the medulla oblongata and thoracic spinal cord, and mild atrophy in cervical spinal cord, which is unusual in the adult form of AxD. She and her daughter’s glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) gene analysis revealed the same heterozygous missense mutation, c.1246C > T, p.R416W, despite of no neurological symptoms in her daughter.

Conclusions

Our case report enriches the understanding of the familial adult AxD. Genetic analysis is necessary when patients have the above mentioned symptoms and signs, MRI findings, especially with family history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alexander disease (AxD, OMIM 203450) is a rare but fatal central nervous system disease. Three subtypes are distinguished upon the onset age: infantile (under age 2), juvenile (age 2 to 12) and adult (over age 12). The infantile form is the most common subtype while the adult onset the least. All subtypes have been described and present with different clinical manifestations. However, the pathological hallmark of the disease is the accumulation of ubiquitinated intracytoplasmic inclusions in astrocytes, called rosenthal fibers, which are composed of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), the main intermediate filament of astrocytes [1].

The adult cases can be distinguished in familial or sporadic form. Here, we present a case of adult onset AxD with family pedigree.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old female was evaluated at our hospital with a 6-year history of progressive neurological symptoms. At age 28, she developed paroxysmal numbness in the left limbs, and two years later she had unilateral limb weakness. She was misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis at the other hospital 2 years after onset. After high-dose pulse methylprednisolone therapy, the illness had no mitigation. The above mentioned symptoms progressively worsened. At age 31, she subsequently developed ataxia, dysarthria, depression, and bowel and bladder urgency with occasional incontinence. And her hands became mild muscle atrophy one year later.

She denied any medical history before. Her mother had a similar neurological symptoms and died within 2 years after onset (at the age of 47), and her maternal aunt also had similar but mild symptoms at the onset age of 54 years old. Her 8-year-old daughter didn’t present with any neurological symptoms but had brain lesions. Other family members were healthy (Fig. 1).

Family pedigree. Black filled symbols represent patients. Grey filled symbols refer to patient’s daughter who had GFAP mutations but without neurological signs or symptoms. Empty symbols represent healthy subjects. Half-filled symbols refer to presumably affected ancestor. Question marks mean subjects potentially affected without neurological signs or symptoms, not examined nor tested for GFAP mutations. Oblique slash means the deceased. Black arrow mark represents the propositus (our patient). Patient III-3 and her daughter (patient IV-4) performed the molecular diagnosis. Although the family member (II-1) had similar psychological manifestations, the detailed medical record was not obtained and not examined for GFAP mutations

Her general medical examination was unremarkable. In neurological examination, she had normal mental status and language testing. The mixed spastic-ataxic dysarthria and horizontal gaze nystagmus were noted. Myokymia was observed in lingualis with weakness of bulbar muscles. Her hands showed mild muscular atrophy. The muscles strength of the bilateral upper-extremities, the left lower-extremity, the right lower-extremity were grade 4, 2, 1, respectively. The increased tendon reflexes and the positive Babinski signs were observed bilaterally. Ataxia was observed in bilateral upper limbs. There was no apparent sensory deficit or extrapyramidal signs. The latest score of modified Rankin scale is 4.

Serum laboratory studies showed unremarkable (complete blood count, routine chemistry test, clotting studies, electrolyte panel, creatinine, glucose, liver and renal function tests, vitamin B12, vitamin E, folic acid, autoimmune antibodies, and infection including hepatitis virus antibodies, Treponema serology, HIV antibodies). Cerebrospinal fluid examination showed a normal opening pressure, the cell count, protein, glucose, IgG index, anti-aquaporin-4 antibody, and intrathecal IgG synthesis rate without oligoclonal bands.

Electroencephalogram, electrophysiological, visual evoked potential, as well as all of the autonomic nervous system testing were all normal 2 years after onset except aural conduction in their brainstem evoked potential.

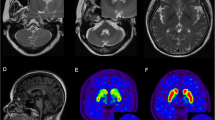

Her brain MRI demonstrated bilateral and symmetric abnormal signals without gadolinium enhancement, which were predominantly distributed in the periventricular, and subcortical white matter. Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) revealed slightly hyperintensity in the periventricular areas. Magnetic resonance angiography was normal [Fig. 2]. The marked atrophy of the medullary oblongata and thoracic spinal cord was seen, while the atrophy of cervical spinal cord was relatively mild. Abnormal T2 hyperintensity was noted in the pyramidal tract of spine. With symptoms progressively worsening, medullary and cerebellar atrophy accelerated [Fig. 3]. Her daughter brain MRI showed abnormality in the periventricular white matter [Fig. 4].

Axial spinal MRI showed hyperintensity involving the corticospinal tracts extends from the carotid 2 (a arrowhead) to carotid 7 cord (b arrowhead) in T2WI image, mild atrophy of cervical spinal cord in sagittal T1WI image (c), severe atrophy of whole thoracic segments in sagittal T2WI image, which is similar to the typical “tadpole” (d), medullary atrophy at 3 years after onset (e, f), and severe medulla and cerebellar atrophy 1 years later (g, h)

Her genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral leucocytes when an informed consent was obtained from the patient and her husband. A heterogeneous missense mutation was detected in exon 8 (c.1246C > T) of the GFAP gene, causing a change of arginine to tryptophan at amino acid position 416 (p.R416W). Her daughter’s genomic DNA showed the same heterozygous mutation but without any neurological symptoms [Fig. 5]. Upon clinical, family history, MRI finding and gene analysis, she was confirmed as adult AxD.

This case with AxD is characterized by typical clinical and MRI findings, especially with family history and adult onset. The heterozygous missense mutation in the GFAP gene, c.1246C > T, p.R416W was identified, which was already shown to be pathogenic in adult onset AxD [2, 3]. It has been reported that adult AxD has various clinical courses. Most cases have a subacute onset and gradually progressive course [2], but some present an acute onset [4]. There is no gender difference. About half of the cases is familial, consistent with autosomal dominant transmission. The mean age of onset is usually in the late thirties. Our patient had pseudobulbar, spastic paresis and ataxia, which are acknowledged as the cardinal triad of the clinical presentations and appear in approximately 70 % of cases [2, 4, 5]. Palatal myoclonus, which is specific and essential for AxD diagnosis, is only observed in one third, especially in hereditary cases [6], not seen in our patient. Nearly 45 % of reported patients had autonomic dysfunction including bowel/bladder dysfunction and orthostatic hypotension [7], which was found in our patient.

Typical MRI findings included marked signal periventricular changes, atrophy of the bulbar region and upper cervical spinal cord in adult AxD [2, 7]. Approximately 90 % cases showed marked medullary atrophy and 50 % had deep white matter lesions or periventricular changes [5]. Farina et al. reported that patients under 40 years old were easier to have periventricular white matter abnormalities and postcontrast enhancement than patients over 40, which showed different levels of abnormal diffusivity On DWI, but some cases were normal [8]. In our case, MRI findings showed the severe atrophy in bulbar region and thoracic spinal cord, but mild atrophy in cervical spinal cord, which is rare in the adult AxD. On DWI, our patient had slightly hyperintensity of extensive periventricular white matter. The lesions without gadolinium enhancement might be related to the decreased amounts and limited distribution of rosenthal fibers [8]. It should be stressed that MRI findings in our case was atypical despite of the lesion locating in the typical regions.

In the radiologic differential diagnosis of adult AxD, several disorders need to be considered [9]. Diseases like degenerative disorders, particularly progressive supranuclear palsy, multisystem atrophy with cerebellar predominance, and various spinocerebellar ataxias often have brain stem and cerebellum atrophy but without lesions in periventricular white matter [8]. Besiedes, some leukodystrophies which are similar to adult AxD were described below (see Table 1) [5, 10–17].

Beside, asymptomatic carriers with MRI abnormalities have been described in some reports [2, 6, 8, 18–23]. Here we listed several asymptomatic carriers similar to our patient’s daughter who had abnormal brain MRI and carrying the gene mutation (see Table 2).

Mutations in the GFAP gene, which lead to the accumulation of ubiquitinated intracytoplasmic inclusions in rosenthal fibers in association with the small heat shock proteins, HSP27 and aB-crystallin [1], are thought to account for more than 95 % of AxD cases [24]. In infantile [3, 25, 26], juvenile [20, 27] and sporadic adult AxD [28–30], the heterozygous missense mutation of the GFAP gene, c.1246C > T, p.R416W, has been reported to be one of the causes of AxD. While In familial adult onset AxD it has been rarely reported. Thyagarajan described a woman and her son with adult onset AxD and the above mutation [31]. They had different clinical manifestations but strikingly similar MRI abnormalities and the same GFAP mutation. It means that molecularly characterized inherited AxD is a cause of symptoms. The same GFAP mutation can cause both early and late onset AxD, and vertical transmission occurs in adult onset AxD with GFAP mutations. Our patient, her mother and maternal aunt had similar neurological manifestations but the latter two had a relative later onset. Nevertheless, her mother’s clinical manifestations deteriorated rapidly, her maternal aunt has mild symptoms with comparatively slow progress. She and her daughter had the same heterozygous missense mutation. All these findings suggest that the familial Adult AxD members can possibly show either similar or different manifestations. The molecular genetic evidence of our AxD family favors that AxD is an autosomal dominant inheritance [32], but further long-term follow-up is needed.

Conclusions

In summary, our case report enriches the understanding of the familial adult AxD. Genetic analysis is necessary when patients have the above mentioned symptoms and signs, MRI findings, especially with family history.

Abbreviations

- AxD:

-

Alexander disease

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DWI:

-

Diffusion Weighted Imaging

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid attenuated inversion recovery

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance angiography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- T1WI:

-

T1-weighted imaging

- T2WI:

-

T2-weighted imaging

References

Iwaki T, Iwaki A, Tateishi J, Sakaki Y, Goldman JE. Alpha B-crystallin and 27-kd heat shock protein are regulated by stress conditions in the central nervous system and accumulate in Rosenthal fibers. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:487–95.

Pareyson D, Fancellu R, Mariotti C, Romano S, Salmaggi A, Carella F, et al. Adult-onset Alexander disease: a series of eleven unrelated cases with review of the literature. Brain. 2008;131:2321–31.

Brenner M, Johnson AB, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Rodriguez D, Goldman JE, Messing A. Mutations in GFAP, encoding glial fibrillary acidic protein, are associated with Alexander disease. Nat Genet. 2001;27:117–20.

Ayaki T, Shinohara M, Tatsumi S, Namekawa M, Yamamoto T. A case of sporadic adult Alexander disease presenting with acute onset, remission and relapse. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:1292–3.

Namekawa M, Takiyama Y, Honda J, Shimazaki H, Sakoe K, Nakano I. Adult-onset Alexander disease with typical “tadpole” brainstem atrophy and unusual bilateral basal ganglia involvement: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:21.

Okamoto Y, Mitsuyama H, Jonosono M, Hirata K, Arimura K, Osame M, et al. Autosomal dominant palatal myoclonus and spinal cord atrophy. J Neurol Sci. 2002;195:71–6.

Balbi P, Salvini S, Fundaro C, Frazzitta G, Maestri R, Mosah D, et al. The clinical spectrum of late-onset Alexander disease: a systematic literature review. J Neurol. 2010;257:1955–62.

Farina L, Pareyson D, Minati L, Ceccherini I, Chiapparini L, Romano S, et al. Can MR imaging diagnose adult-onset Alexander disease? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1190–6.

Romano S, Salvetti M, Ceccherini I, et al. Brainstem signs with progressing atrophy of the medulla oblongata and upper cervical spinal cord. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:562–70.

Rodriguez D. Leukodystrophies with astrocytic dysfunction. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;113:1619–28.

Leite CC, Lucato LT, Santos GT, Kok F, Brandão AR, Castillo M. Imaging of adult leukodystrophies. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72:625–32.

van Rappard DF, Boelens JJ, Wolf NI. Metachromatic leukodystrophy: disease spectrum and approaches for treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29:261–73.

Graff-Radford J, Schwartz K, Gavrilova RH, Lachance DH, Kumar N. Neuroimaging and clinical features in type II (late-onset) Alexander disease. Neurology. 2014;82:49–56.

Kinoshita M, Kondo Y, Yoshida K, Fukushima K, Hoshi K, Ishizawa K, et al. Corpus callosum atrophy in patients with hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with neuroaxonal spheroids: an MRI-based study. Intern Med. 2014;53:21–7.

Lynch DS, Jaunmuktane Z, Sheerin UM, Phadke R, Brandner S, Milonas I, et al. Hereditary leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids: a spectrum of phenotypes from CNS vasculitis to parkinsonism in an adult onset leukodystrophy series. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:512–9.

Kinoshita M, Yoshida K, Oyanagi K, Hashimoto T, Ikeda S. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids caused by R782H mutation in CSF1R: case report. J Neurol Sci. 2012;318:115–8.

van der Knaap MS, van der Voorn P, Barkhof F, Van Coster R, Krägeloh-Mann I, Feigenbaum A, et al. A new leukoencephalopathy with brainstem and spinal cord involvement and high lactate. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:252–8.

Wada Y, Yanagihara C, Nishimura Y, Namekawa M. Familial adult-onset Alexander disease with a novel mutation (D78N) in the glial fibrillary acidic protein gene with unusual bilateral basal ganglia involvement. J Neurol Sci. 2013;331:161–4.

Yoshida T, Sasayama H, Mizuta I, Okamoto Y, Yoshida M, Riku Y, et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein mutations in adult-onset Alexander disease: clinical features observed in 12 Japanese patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124:104–8.

Gorospe JR, Naidu S, Johnson AB, Puri V, Raymond GV, Jenkins SD, et al. Molecular findings in symptomatic and pre-symptomatic Alexander disease patients. Neurology. 2002;58:1494–500.

Balbi P, Seri M, Ceccherini I, Uggetti C, Casale R, Fundarò C, et al. Adult-onset Alexander disease : report on a family. J Neurol. 2008;255:24–30.

Shiihara T, Sawaishi Y, Adachi M, Kato M, Hayasaka K. Asymptomatic hereditary Alexander’s disease caused by a novel mutation in GFAP. J Neurol Sci. 2004;225:125–7.

Sugiyama A, Sawai S, Ito S, Mukai H, Beppu M, Yoshida T, et al. Incidental diagnosis of an asymptomatic adult-onset Alexander disease by brain magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative evaluation. J Neurol Sci. 2015;354:131–2.

Messing A, Brenner M, Feany MB, Nedergaard M, Goldman JE. Alexander disease. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5017–23.

Iwaki A, Iwaki T, Goldman JE, Ogomori K, Tateishi J, Sakaki Y. Accumulation of alpha B-crystallin in brains of patients with Alexander’s disease is not due to an abnormality of the 5′-flanking and coding sequence of the genomic DNA. Neurosci Lett. 1992;140:89–92.

Reichard EA, Ball Jr WS, Bove KE. Alexander disease: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1996;16:327–43.

Li R, Johnson AB, Salomons G, Goldman JE, Naidu S, Quinlan R, et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein mutations in infantile, juvenile, and adult forms of Alexander disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:310–26.

Caroli F, Biancheri R, Seri M, Rossi A, Pessagno A, Bugiani M, et al. GFAP mutations and polymorphisms in 13 unrelated Italian patients affected by Alexander disease. Clin Genet. 2007;72:427–33.

van der Knaap MS, Ramesh V, Schiffmann R, Blaser S, Kyllerman M, Gholkar A, et al. Alexander disease: ventricular garlands and abnormalities of the medulla and spinal cord. Neurology. 2006;66:494–8.

Kinoshita T, Imaizumi T, Miura Y, Fujimoto H, Ayabe M, Shoji H, et al. A case of adult-onset Alexander disease with Arg416Trp human glial fibrillary acidic protein gene mutation. Neurosci Lett. 2003;350:169–72.

Thyagarajan D, Chataway T, Li R, Gai WP, Brenner M. Dominantly-inherited adult-onset leukodystrophy with palatal tremor caused by a mutation in the glial fibrillary acidic protein gene. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1244–8.

Wohlwill FJ, Bernstein J, Yakovlev PI. Dysmyelinogenic leukodystrophy; report of a case of a new, presumably familial type of leukodystrophy with megalobarencephaly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1959;18:359–83.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient’s family and the Beijing JinZhun Gene Technology Co., Ltd. The work couldn’t be done without their participation and help.

Funding

We receive no funding support.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable. For protecting patient privacy.

Authors’ contributions

Study design and drafting of manuscript: YL, XZ. Clinical study perform: YL, XZ, HZ. Genetic analysis: HZ, HW. Acquisition and interpretation of data: YL, XG, AZ, LZ, XL. Critical revision of the manuscript: XH, HW, YL. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consents were obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report has been approved by the Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University’s Research Ethics Board. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her families for genetic analysis and publication of this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Zhou, H., Wang, H. et al. Atypical MRI features in familial adult onset Alexander disease: case report. BMC Neurol 16, 211 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0734-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0734-9