Abstract

Background

Non-adherence to medication is a common and complex issue faced by individuals undergoing hemodialysis (HD). However, more knowledge is needed about modifiable factors influence on non-adherence. This study investigated the prevalence of non-adherence, medication beliefs and symptom burden and severity among patients receiving HD in Denmark. Associations between non-adherence, medications beliefs and symptom burden and severity were also explored.

Method

A cross-sectional questionnaire-based multisite study, including 385 participants. We involved patient research consultants in the study design process and the following instruments were included: Medication Adherence Report Scale, Beliefs about Medication Questionnaire and Dialysis Symptom Index. Logistic regression analysis was performed.

Results

The prevalence of non-adherence was 32% (95% CI 27–37%) using a 23-point-cut-off. Just over one third reported being concerned about medication One third also believed physicians to overprescribe medication, which was associated with 18% increased odds of non-adherence. Symptom burden and severity were high, with the most common symptoms being tiredness/ lack of energy, itching, dry mouth, trouble sleeping and difficulties concentrating. A high symptom burden and/or symptom severity score was associated with an increased odd of non-adherence.

Conclusion

The study found significant associations between non-adherence and, beliefs about overuse, symptom burden and symptom severity. Our results suggest health care professionals (HCP) should prioritize discussion about medication adherence with patients with focus on addressing patient-HCP relationship, and patients’ symptom experience. Future research is recommended to explore the effects of systematically using validated adherence measures in clinical practice on medication adherence, patient-HCP communication and trust. Additionally, studies are warranted to further investigate the relationship between symptom experience and adherence in this population.

Trial registration

NCT03897231.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medication adherence is: “the extent to which a person’s behavior of taking medication corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider” [1]. Patients with End Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) undergoing hemodialysis (HD) cope with a demanding medication regime, that includes multiple medications, health care appointments with medication regulation, renewal of prescriptions and continuously having to adapt their medication behavior to the prescribed regime [2, 3]. Not surprisingly, non-adherence to medication is prevalent among this patient population, with estimates ranging from 12–98% [4, 5]. Non-adherence increases the risk of disease progression, rising health care costs due to hospitalization, and premature death [5,6,7].

The issue of non-adherence among patients in HD is multifaceted and several demographic factors have been suggested to be associated with non-adherence including young age, non-Caucasian ethnicity, female gender, living alone and low educational level. Clinical factors include longevity of HD, concurrent diseases and high pill burden [5]. Other factors are modifiable, meaning they can be changed or addressed to improve adherence. A recent metanalysis found that negative beliefs about medication among a wide range of chronic conditions, were associated with non-adherence [8]. This indicates that the motivation of patients to initiate and adhere to treatment is shaped by their own beliefs and preferences [3]. Cultural variations have been found across countries. Nevertheless, non-adherence among patients undergoing HD in Scandinavia is sparsely researched [8]. The UCSF Symptom Management Model describes a complex and two-way connection between symptom experience, patients’ beliefs and adherence [9,10,11]. Patient-reported symptoms have been consistently associated to medication adherence in patients living with HIV [12]. Thus, studies have found that a high quantity of symptoms, also called symptom burden, was associated with poorer medication adherence [9, 12]. Patients in HD report a high prevalence of physical and emotional symptoms throughout the literature [13,14,15,16]. It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that symptom burden also impacts adherence in the HD population. However, research investigating association between symptom burden and non-adherence in HD settings is limited.

Aims

The aims of this study were therefore to investigate 1) the prevalence of non-adherence 2) patients’ beliefs about medication 3) symptom burden and severity and 4) associations between beliefs about medication, symptom burden and severity and non-adherence in patients receiving HD.

Materials and methods

A multi-site cross-sectional study was conducted from April 2019 – December 2020 at four University Hospitals in the Capital Region of Denmark, involving patients with ESKD receiving HD treatment in a hospital-based outpatient center.

Patient involvement

We involved patients in the study design process to increase patient recruitment and obtain relevant knowledge applicable to the HD population. We built on an already well-established collaboration with one patient research consultant (PRC) [17]. Three additional PRCs were recruited by this consultant. All had current or previous experience with HD treatment and represented diverse ages, gender and education.

We held two workshops. In the first workshop TMN introduced a sample of possible instruments related to medication adherence and questions for collecting basic demographic data. The PRCs were asked to identify the variables that mattered the most to them in relation to medicine taking. This resulted in removal of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life questionnaire (KDQOL) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and to the inclusion of the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS), Beliefs about Medication Questionnaire (BMQ) and the Dialysis Symptom Index (DSI). In the following workshop, the PRCs commented on the study information leaflet. Additionally, they pilot-tested and evaluated the clarity, difficulty, and appropriateness of the Danish translation of MARS and DSI. The preliminary version of the entire survey was subsequently discussed via phone and email, and the final version of the questionnaire prepared.

Procedure

Participants who were ≥ 18 years of age, who had been undergoing HD treatment ≥ 3 month at a hospital-based outpatient HD Center were approached by their allocated nurses during dialysis and informed about the study. Participants who were judged by the health care professional (HCP) as not able to answer questions due to cognitive impairment, psychiatric disorder or not being able to understand or speak Danish were excluded. Those who wished to participate provided informed consent and completed a paper-based questionnaire. Patients who had visual or physical impairments or difficulty reading Danish were interviewed using a structured interview approach.

Sample size

Sample size was determined based on the precision of the non-adherence prevalence estimate. With an expected 50% prevalence of non- adherence and a 95% confidence interval (CI) with a 5% ± margin of error, 385 participants were required.

Data collection

The questionnaire consisted of demographic and clinical data and the following instruments; MARS to assess medicine taking behavior [18], BMQ to assess medication beliefs [19] and DSI to measure physical and emotional symptoms and their severity [13]. Please refer to Table 1 to get a full overview of the instruments applied. Before collecting data MARS and DSI underwent translation from English into Danish followed a three-step process inspired by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORCT) translation procedure [20].

Demographic and clinical data included social security number, gender, age, country of birth, living arrangements, marital status, education, occupation, comorbidities, type of dialysis, longevity of HD, kidney transplantation history and daily pill burden. Daily pill burden was calculated based on the daily pill count and applied exclusively to oral medications, excluding medications prescribed pro nececsitate.

All data were entered into REDCap by a project nurse. Followed by a screening for typing errors and missing values. Based on the screening, our assumption was, that the missing values occurred randomly. Therefore, if more than two items were missing in MARS, BMQ and DSI, the missing items were replaced with the average of the other items.

Confounders

Potential confounders included gender, age, country of birth, living arrangements, marital status, comorbidities, longevity of HD and daily pill burden. The confounders were selected based on previous research indicating their significant association with non-adherence [5]. Due to symptoms being associated to medication adherence in other patient populations [12] both symptom burden and symptoms severity were selected as potential confounders to necessity, concern, harm and overuse in the BMQ.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as means with standard deviations (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on distribution of data. Categorical data are presented as count with percentages. The results for individual BMQ sub-scales are presented as percentages over midscale scores and as medians with IQRs. The DSI scores are presented as medians and IQRs. Prevalence estimates are presented as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Associations between independent variables (necessity, concern, harm, overuse, symptom severity score, symptom burden score) and our dependent variable (non-adherence), were analyzed using logistic regression modelling. Each variable was fitted into an unadjusted model and models controlling for possible effects of confounders. Confounders were evaluated individually, by comparison of the unadjusted independent variable estimate with the independent variable estimate in the models adjusting for each confounder separately. The final adjusted regression model included the three confounders that had the greatest change on the independent variable estimate (please see supplementary material for an overview of the analyses conducted). Model estimates were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) and P-values. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. We used Hosmer–Lemeshow test to evaluate goodness-of-fit and the Bonferroni correction to account for multiple testing by upscaling p-values with the number of tests performed. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.25.0

Results

A total of 385 patients were enrolled in the study (Fig. 1). The majority (two thirds) were male patients, elderly of age, and had attended HD treatment for > 2 years. Nearly one third had a level of education equivalent to university. Please see Table 2 for patient characteristics.

Prevalence of non-adherence

Based on a cut-off score < 23 points in the MARS assessment, 32% (95% CI 27–37%) were identified as non-adherent to their prescribed medications. However, when the cut-off score was altered to < 25 points, the number of non-adherent participants increased to 73% (CI 69–77%). Forgetfulness was the most frequent reason for non-adherence, cited by 62% of participants. Altering the dose was the second most frequent reason, with 36% of participants reporting doing so rarely or often (Table 3).

Patients’ beliefs about medication

The BMQ revealed that while most participants believed medication to be necessary, a large proportion expressed concern about taking them. Although the majority did not consider medication to be harmful, 35% believed physicians overuse medication in general. The necessity and concern differential were 7, with 86% scoring positively, indicating a belief that the benefits of medication outweighed their concern. However, 14% of participants (n = 53) scored zero or below, suggesting a higher concern for medication than a sense of necessity (Table 4).

Prevalence and severity of physical and emotional symptoms

The median symptom burden score was 10 (IQR 5–16) with a minimum score of 0 (n = 20) and maximum score of 30 (n = 1). Similarly, the median score for total symptom severity score was 30 (IQR 14–53), with the lowest reported score being 0 (n = 20) and the highest reported score being 106 (n = 1). The most prominent symptoms were feeling tired/lack of energy (77%), itching (54%), dry mouth (52%), lightheadedness/dizziness (42%), trouble falling asleep/staying asleep (46%) and difficulty concentrating (39%) (Fig. 2).

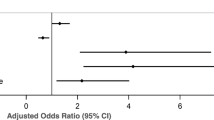

Non-adherence and patients’ beliefs about medication

After adjusting for confounding variables, only beliefs about overuse (OR = 1.18, CI = 1.09–1.27) were significantly associated with non-adherence (Table 5).

Non-adherence and patient experienced symptoms burden and severity

Symptom severity (OR = 1.02, CI = 1.01–1.03) and symptom burden score (OR = 1.09, CI = 1.05–1.13) were significantly associated with non-adherence (Table 5).

Discussion

This study investigated the prevalence of non-adherence, patients’ beliefs about medication and the prevalence and severity of physical and emotional symptoms among Danish patients receiving HD. Potential associations between beliefs about medications, symptom burden- and severity and non-adherence were also investigated.

The prevalence of non-adherence was assessed to 32% using a 23-point cut-off in the MARS. However, when adjusting the cut-off to 25-points, non-adherence increased to 73%. Both results fall within the range of previously reported rates observed in other HD settings (ranging from 12 to 98%) [5]. The results also underscore the challenge posed by inconsistent definitions of non-adherence, contributing to the substantial variation in prevalence rates across studies. Surprisingly, 27% of participants reported in MARS that they never missed a dose, suggesting possible challenges with recall bias and over/under estimation when using self-report questionnaires to assess non-adherence [26, 27]. Nevertheless, self-report measures are valuable tools for evaluating medication adherence as they capture subjective experiences and perceptions [27]. Accordingly, our study emphasizes the relevance of using PROMs routinely in clinical practice, both to monitor adherence and as a starting point for HCPs to discuss and support patients in their medication taking efforts.

Most participants believed medication to be necessary, although over one third reported concerns about taking them. The majority did not consider medication to be harmful, but one third believed that physicians in general overused medication. These findings resonate with previous research [8, 26, 28]. Drangsholt et al. similarly found a high necessity score of 98% and a low concern score of 34% in a Norwegian HD population [28]. This similarity may be explained by shared cultural values [8]. Nevertheless, the findings illustrate the complex interplay between patients having to struggle with being dependent on medication and at the same time harboring concerns about taking them and the belief that medication is overprescribed by physicians.

Notably, our results revealed 18% increased odds when harboring the belief that physicians overuse medications. This aligns with a recent study among patients with asthma, showing a 40% decrease in adherence when believing physicians to overuse medication [29]. It has been suggested that the nature of the patient-HCP relationship, particularly in relation to miscommunication and mistrust, may be linked to this association [30]. Both miscommunication and mistrust have previously been reported by patients as barriers to adherence [31]. The absence of systematic screening of adherence and standardized approaches among physicians and nurses to supporting adherence may also contribute. Time and resource limitations may also challenge comprehensive alignment of medication and treatments goals with patients [17]. Thus, it can be difficult to meet patients where they are in relation to beliefs, wishes and values, moreover, involve patients actively in decisions about medication. In contrast, our study did not find an association between non-adherence and beliefs about necessity, concern,and harm, as reported in other studies. This might relate to differences across countries, languages and cultures, as described by Horne et al. [8].

Participants reported a high symptom burden and severity score consistent with previous HD studies [15, 32]. Higher symptom burden and severity were found to be significantly associated with non-adherence. Thus, similar to studies of patients living with HIV [9, 33]. Considering the impact of the symptom’s patient reported, it is perhaps not surprising that 32% of the participants exhibited non-adherent behavior. Difficulty concentrating, trouble sleeping and feeling tired are all symptoms that inadvertently could affect an individual’s ability to remember and adhere to complex dosing instructions. Additionally, dry mouth could easily hinder one’s ability to swallow pills, particularly for individuals’ who must adhere to strict fluid restrictions and at the same time take a substantial daily number of pills. Research has shown that patients with ESKD often experience symptom clusters that can impact related symptoms negatively [9, 16]. Zhou et al. describe five independent symptom clusters: gastro-intestinal discomfort, sleep disorder, skin discomfort and mood [16]. Nevertheless, regular symptom assessment lack standardization in dialysis settings, with limited treatment choices due to scarce evidence [32]. Moreover, research has identified a substantial discordance between patients experience of symptoms and those that are recognized by the HCP [32, 34]. Our results underscore the existing knowledge of the importance of HCPs to prioritize symptom management in this patient population. We propose incorporating validated patient reported outcome measures for routine screening and improving patient centered communication and care, aligning with recent KDIGO recommendation [32]. Exploring the potential of mobile applications to monitor and direct attention to symptoms during consultations has demonstrated promise in improving both symptom management and adherence to oral anticancer treatment [35]. Therefore, this area may be worth investigating in future research.

The strengths of this study include the multi-site design, the involvement of PRCs, the use of validated questionnaires and the relatively large sample size. However, a key limitation include the use of a cross-sectional design, which captures a moment, lack causality, thus affecting the generalizability of our study [36,37,38]. The choice of not including an assessment of depression and anxiety can also be seen as a limitation. Furthermore, the participants in our study were characterized by being older and having a higher degree of education, than those included in similar studies. Lastly, we did not conduct any analysis of patients who declined to participate.

In conclusion, the prevalence of non-adherence was 32% (95% CI = 27–37%). Patients’ beliefs about overuse were significantly associated with non-adherence, while patients’ beliefs about necessity, concern and harm were not. Moreover, symptom burden and severity were significantly associated with non-adherence with some of the most prominent symptoms being feeling tired/lack of energy, itching, dry mouth, lightheadedness/dizziness, trouble falling asleep/staying asleep and difficulties concentrating. Our results suggest HCP should prioritize discussions about medication adherence with patients, focus on addressing the patient-HCP relationship and patients’ symptom experience. Our results suggest HCPs should prioritize discussions about medication adherence with patients, focus on addressing the patient-HCP relationship and patients’ symptom experience. Future research is recommended to explore the effects on systematically using validated adherence measures in clinical practice on medication adherence, patient-HCP communication and trust. Furthermore, studies are warranted to delve deeper into the relationship between symptom burden and adherence in this population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMQ:

-

Beliefs about medicine questionnaire

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DSI:

-

Dialysis symptom index

- EORCT:

-

European organization for research and treatment of cancer

- ESKD:

-

End stage kidney disease

- HADS:

-

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

- HD:

-

Hemodialysis

- HCP:

-

Health care professional

- IBM SPSS:

-

International business machine cooperation statistical package for the social sciences

- IQR:

-

Interquartile ranges

- KDQOL:

-

Kidney disease quality of life

- MARS:

-

Medication adherence report scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PRC:

-

Patient research consultant

- SD:

-

Standard diviation

References

World Health O. Adherence to long-term therapies : evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

Clark S, Farrington K, Chilcot J. Nonadherence in dialysis patients: prevalence, measurement, outcome, and psychological determinants. Semin Dial. 2014;27(1):42–9.

Mechta Nielsen T, Frøjk Juhl M, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Thomsen T. Adherence to medication in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of qualitative research. Clin Kidney J. 2018;11(4):513–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfx140.

Cukor D, Rosenthal DS, Jindal RM, Brown CD, Kimmel PL. Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2009;75(11):1223–9.

Ghimire S, Castelino RL, Lioufas NM, Peterson GM, Zaidi ST. Nonadherence to medication therapy in haemodialysis patients: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144119.

Denhaerynck K, Manhaeve D, Dobbels F, Garzoni D, Nolte C, De Geest S. Prevalence and consequences of nonadherence to hemodialysis regimens. Am J Crit Care. 2007;16(3):222–35 quiz 36.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97.

Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the necessity-concerns framework. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12): e80633.

Gay C, Portillo CJ, Kelly R, Coggins T, Davis H, Aouizerat BE, et al. Self-reported medication adherence and symptom experience in adults with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22(4):257–68.

Bender MS, Janson S, Franck LS, Lee K. Theory of symptom management. In: Smith MJ, editor. Middle Range Theory for Nursing. Fourth ed. New York; Springer Publishing Company; 2018. p. 147–77.

Dodd M, Janson S, Facione N, Faucett J, Froelicher ES, Humphreys J, et al. Advancing the science of symptom management. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(5):668–76.

Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, Castelli F, Narciso P, Noto P, et al. Correlates and predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: overview of published literature. JAIDS J Acqu Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31:S123–7.

Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Rotondi AJ, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, et al. Development of a symptom assessment instrument for chronic hemodialysis patients: the dialysis symptom index. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2004;27(3):226–40.

Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2009;4(6):1057–64.

You AS, Kalantar SS, Norris KC, Peralta RA, Narasaki Y, Fischman R, et al. Dialysis symptom index burden and symptom clusters in a prospective cohort of dialysis patients. J Nephrol. 2022;35(5):1427–36.

Zhou M, Gu X, Cheng K, Wang Y, Zhang N. Exploration of symptom clusters during hemodialysis and symptom network analysis of older maintenance hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2023;24(1):115.

Mechta Nielsen T, Schjerning N, Kaldan G, Hornum M, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Thomsen T. Practices and pitfalls in medication adherence in hemodialysis settings – a focus-group study of health care professionals. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):315.

Horne R, Weinman J. Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):17–32.

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14(1):1–24.

Dagmara Kuliś AB, Galina Velikova, Eva Greimel, Michael Koller. Eortc quality of life group translation procedure. 2017;1-26

Vluggen S, Hoving C, Schaper NC, De Vries H. Psychological predictors of adherence to oral hypoglycaemic agents: an application of the ProMAS questionnaire. Psychol Health. 2020;35(4):387–404.

Lee CS, Tan JHM, Sankari U, Koh YLE, Tan NC. Assessing oral medication adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with polytherapy in a developed Asian community: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9): e016317.

Kang GCY, Koh EYL, Tan NC. Prevalence and factors associated with adherence to anti-hypertensives among adults with hypertension in a developed Asian community: a cross-sectional study. Proc Singapore Healthc. 2020;29(3):167–75.

Koster ES, Philbert D, Winters NA, Bouvy ML. Adolescents’ inhaled corticosteroid adherence: the importance of treatment perceptions and medication knowledge. J Asthma. 2015;52(4):431–6.

Sjölander M, Eriksson M, Glader E-L. The association between patients’ beliefs about medicines and adherence to drug treatment after stroke: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003551.

Wileman V, Farrington K, Wellsted D, Almond M, Davenport A, Chilcot J. Medication beliefs are associated with phosphate binder non-adherence in hyperphosphatemic haemodialysis patients. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;20(3):563–78.

Stirratt MJ, Dunbar-Jacob J, Crane HM, Simoni JM, Czajkowski S, Hilliard ME, et al. Self-report measures of medication adherence behavior: recommendations on optimal use. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5(4):470–82.

Drangsholt SH, Cappelen UW, von der Lippe N, Høieggen A, Os I, Brekke FB. Beliefs about medicines in dialysis patients and after renal transplantation. Hemodial Int. 2019;23(1):117–25.

Brandstetter S, Finger T, Fischer W, Brandl M, Böhmer M, Pfeifer M, et al. Differences in medication adherence are associated with beliefs about medicines in asthma and COPD. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;7:39.

Shahin W, Kennedy GA, Stupans I. The consequences of general medication beliefs measured by the beliefs about medicine questionnaire on medication adherence: a systematic review. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020;8(3):147.

Mechta Nielsen T, Frøjk Juhl M, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Thomsen T. Adherence to medication in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of qualitative research. Clin Kidney J. 2018;11(4):513–27.

Mehrotra R, Davison SN, Farrington K, Flythe JE, Foo M, Madero M, et al. Managing the symptom burden associated with maintenance dialysis: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2023;104(3):441–54.

Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Llabre MM, Durán RE, Antoni MH, Schneiderman N, et al. Physical symptoms, beliefs about medications, negative mood, and long-term HIV medication adherence. Ann Behav Med : Publ Society Behav Med. 2007;34(1):46–55.

Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Unruh ML, Palevsky PM, et al. Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2007;2(5):960–7.

Karaaslan-Eşer A, Ayaz-Alkaya S. The effect of a mobile application on treatment adherence and symptom management in patients using oral anticancer agents: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;52:101969.

Wang X, Cheng Z. Cross-Sectional Studies: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Recommendations. Chest. 2020;158(Supplement 1):S65–71.

Jager KJ, Tripepi G, Chesnaye NC, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, Stel VS. Where to look for the most frequent biases? Nephrology (Carlton). 2020;25(6):435–41.

Sedgwick P. Bias in observational study designs: cross sectional studies. BMJ. 2015;350:h1286.

Danish law on ethics in health care research. https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2020/1338. Accessed 26 Oct 2023.

Editorial TL. Should protocols for observational research be registered? The Lancet. 2010;375(9712):348.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the patient research consultants for their valuable contributions in conducting this study and University Hospital Rigshospitalet, University Hospital Herlev and University Hospital Hillerød for their valuable help with recruiting patients.

Thank you also to Ingrid Egerod RN, PhD, Professor Emerita Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. Copenhagen, Denmark and Mary Jarden RN, PhD, Professor, Head of Research Nursing at Center for Cancer and Organ Diseases, Copenhagen University Hospital—Rigshospitalet. Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. Copenhagen, Denmark for their valuable contributions regarding translation in our study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Library, Copenhagen University Library Research reported in this article was funded through the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF17OC0029778) (NNF18OC0052951). The views presented are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content. This participation includes Writing protocol: Trine Mechta Nielsen, Bo Feldt-Rasmussen, Mads Hornum, Thordis Thomsen. Collection of data: Trine Mechta Nielsen, Trine Marott. Analysis and interpretation of data: Trine Mechta Nielsen, Bo Feldt-Rasmussen, Mads Hornum, Thomas Kallemose, Thordis Thomsen. Drafting the manuscript: Trine Mechta Nielsen, Thordis Thomsen. Critical appraisal and approval of the final manuscript: Trine Mechta Nielsen, Trine Marott, Bo Feldt-Rasmussen, Mads Hornum, Thomas Kallemose, Thordis Thomsen.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and content to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Danish Regional Ethics Committee on Health Research deemed the study exempt from formal ethical approval (19017580). According to Danish legislation, cross sectional studies, do not require formal ethic approval [39]. The study also underwent evaluation by the Danish Regional Data Protection Agency and obtained formal data approval (VD-2019–89). According to Danish legislations, all studies handling patient data, require formal data approval. The study protocol was registered at WHO compatible study register platform (Clin.Trail.Gov: NCT03897231) [40]. All participants gave informed consent, after receiving written and verbal information about confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the right to withdraw.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary material. Overview of analysis with variables and confounders.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mechta Nielsen, T., Marott, T., Hornum, M. et al. Non-adherence, medication beliefs and symptom burden among patients receiving hemodialysis -a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 24, 321 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-023-03371-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-023-03371-3