Abstract

Background

Following the strong recommendation for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) vaccination, many patients with medical comorbidities are being immunized. However, the safety of vaccination in patients with autoimmune diseases has not been well established. We report a new case of biopsy-proven IgA vasculitis with nephritis presenting as a nephrotic syndrome after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in a patient with a history of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Case presentation

A 76-year-old man with a history of cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis presented with purpura in both lower limbs, followed by nephrotic syndrome after the second dose of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Skin and renal biopsy revealed IgA vasculitis with nephritis. The patient’s past medical history of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and features of chronicity in renal pathology suggest an acute exacerbation of preexisting IgA vasculitis after COVID-19 vaccination. After the steroid and renin-angiotensin system inhibitor use, purpura and acute kidney injury recovered within a month. Subnephrotic proteinuria with microscopic hematuria remained upon follow-up.

Conclusion

Physicians should keep in mind the potential (re)activation of IgA vasculitis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. It is important to closely monitor COVID-19 vaccinated patients, particularly those with autoimmune diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global COVID-19 vaccine campaign has been actively underway to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. mRNA COVID-19 vaccines deliver lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA, which encodes the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein and triggers robust innate and adaptive immune responses [1,2,3]. The efficacy and safety of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 have been demonstrated in clinical trials and real-world studies [4,5,6,7]. However, the safety of vaccination in patients with autoimmune diseases has not been well established.

Recently, de novo or relapsing glomerulonephritis (GN) following mRNA COVID-19 vaccines has been reported. IgA nephropathy was the most common GN among them, where most cases presented with gross hematuria shortly after the first or second dose of vaccination [8,9,10].

There is no diagnostic tool to prove the causality between GN and mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. However, the consistency of case reports may be related to its pathogenesis and will help to make a hypothesis to prove the causality, which will also help manage kidney disease properly. Herein, we report a new case of biopsy-proven IgA vasculitis with nephritis presenting as a nephrotic syndrome following the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a patient with a history of cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Case presentation

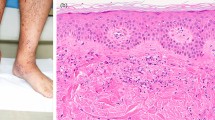

The patient is a 76-year-old man with a history of leukocytoclastic vasculitis treated with immunosuppression therapy ten years ago and has been in remission with no medication. At that time, he presented with palpable purpuric rash on both lower limbs and had no other systemic signs of vasculitis such as abdominal pain, arthralgia, proteinuria, or decreased renal function. Skin biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis, even though immunofluorescence staining was not performed. He was treated with oral prednisolone (20 mg per day) for two weeks, followed by oral azathioprine (25 mg per day) for six months since his skin lesions were severe and progressive. He visited the dermatology outpatient clinic with a sudden-onset purpuric rash on both lower extremities. Ten days prior to his visit, he received the second dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (BioNTech-Pfizer). He had no history of COVID-19 infection or other recent respiratory, urinary or gastrointestinal disease and denied any symptoms between the first dose and the second dose of the mRNA vaccine. He was afebrile, and other vital signs were unremarkable. On physical examination, hemorrhagic papulovesicular lesions distributed on both lower legs were observed (Fig. 1a). The serum creatinine level was 1.06 mg/dL (eGFR 60 mL/min/1.73 m²), and urinalysis was not performed at that time. Skin biopsy was performed and revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 1b). Oral prednisolone 20 mg per day for two weeks was prescribed, and the skin lesions began to be gradually relieved.

However, on day 30 after vaccination (second dose), diffuse abdominal pain and diarrhea were reported. On day 45 after vaccination (second dose), he was referred to the Department of Nephrology for worsening peripheral edema and was hospitalized. Vital signs were unremarkable except for a blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg. Physical examination revealed 3 + pretibial pitting edema with multiple purpuric rashes on both lower limbs.

Serum creatinine increased from 1.06 to 1.42 mg/dL (eGFR decreased from 60 to 48 mL/min/1.73 m²), and serum albumin decreased from 3.8 to 2.7 g/dl. Nephrotic-range proteinuria was observed; urinalysis showed 4 + protein, 10–19 red blood cells (RBCs)/high power field (HPF), and 10–19 white blood cells (WBCs)/HPF, and the spot urine protein/creatinine ratio (UPCR) was 9.01 mg/mg. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen and antibodies to hepatitis C virus were negative; C3 and C4 were within normal reference ranges; tests for anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies, and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies were negative. The polymerase chain reaction test for COVID-19 (nasopharyngeal swab) was negative. Renal sonography revealed normal-sized kidneys with normal parenchymal echogenicity. Table 1 summarizes clinical information.

A kidney biopsy was performed 45 days after the second dose of vaccine. In total, 27 glomeruli were identified, 4 of which showed global sclerosis, 10 glomeruli showed cellular or fibrocellular crescents, and 2 glomeruli showed segmental sclerosis. Focal severe tubular atrophy with infiltration of mononuclear cells and fibrosis in the interstitium were observed in approximately less than 10% of the cortical area. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed predominant mesangial IgA staining with partial peripheral staining, which is compatible with IgA nephritis (Fig. 2a). Electron microscopy revealed moderate amounts of mesangial deposits with podocytes, which showed focal foot process effacement (Fig. 2b).

Renal biopsy findings. a Immunofluorescence images captured on an Axioplan2 microscope (Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany) equipped with HXP 120 V lamp, a 12 bit Axiocam CCD camera (Zeiss), a motorized object desk and filter changer were controlled by SFM software (3DHistech Ltd, Budapest, Hungary) shows predominant mesangial IgA staining with partial peripheral staining (original magnification x400); b Electron microscopy (Hitachi H-7100, Tokyo, Japan) shows moderate amounts of mesangial deposits and focal moderate effacement of epithelial cell foot processes (original magnification x8000)

With the diagnosis of IgA vasculitis with nephritis presenting as nephrotic syndrome, intravenous methylprednisolone 250 mg was given for three consecutive days, followed by oral prednisolone 50 mg per day with olmesartan 40 mg daily. One week later, serum creatinine decreased to 1.04 mg/dL, the UPCR was 8.07 mg/mg, and he was discharged with continued prednisolone and olmesartan. At the 2-month follow-up, the rash and edema were much improved. Serum creatinine level was 1.03 mg/dL, and the UPCR was reduced to 1.97 mg/mg. After that, prednisolone was tapered gradually over four months. Six months after the start of the patient’s treatment, his serum creatinine level was 1.0 mg/dL, the UPCR had decreased to 1 mg/mg, and the microscopic hematuria remained. The drugs were well tolerated, with no significant adverse effects.

Discussion and conclusions

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, de novo or relapsing glomerulonephritis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination has been reported. IgA nephropathy is the most common GN after receiving the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, followed by minimal change disease [8,9,10]. In the literature, 47 cases of IgA nephropathy following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination have been reported (30 de novo and 17 flare-ups) thus far [3, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Gross hematuria within 1–2 days after vaccination was the most common initial presentation, followed by acute kidney injury. Symptoms tended to appear after the second dose of the vaccine instead of after the first dose of the vaccine. Most cases spontaneously resolved with supportive care, such as renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, but in a few cases, immunosuppressive therapy was applied.

Compared to previous cases, our patient initially presented with palpable purpura on the lower limbs followed by nephrotic syndrome, not gross hematuria, and it occurred relatively late after the second dose of vaccine. In addition, skin and renal biopsy revealed IgA vasculitis with nephritis. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that IgA vasculitis coincidently occurred after the COVID-19 vaccination in our case, the past medical history of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and the features of chronicity in renal pathology suggest the possibility that the COVID-19 vaccination triggered an acute exacerbation of preexisting IgA vasculitis. However, it is impossible to confirm whether IgA deposits were present in the kidney tissue before the COVID-19 vaccination since the patient had never performed a renal biopsy before the COVID-19 vaccination.

Nephrotic syndrome is a rare presentation of IgA nephropathy [41]. Indeed, to our knowledge, only three previous cases [22, 36] described biopsy-proven IgA vasculitis with severe glomerulonephritis after Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination, which presented with nephrotic syndrome. Histopathologically, two cases [36] were IgA nephropathy with glomerular capillary IgA deposition, a rare subtype of IgA nephropathy, and one case [22] showed necrotizing cellular crescent formation. Despite intensive initial immunosuppressive treatment, its severe glomerulonephritis took a long time to recover.

The safety and efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs in treating adult-onset IgA vasculitis with renal involvement are not well established. Almost all data come from studies carried out in children or patients with IgA nephropathy or IgA-crescentic glomerulonephritis [42]. Usually, immunosuppressive therapy is not recommended as the initial treatment of choice for patients with IgA nephropathy in adults. It is recommended only for those at high risk of progressive chronic kidney disease despite maximal supportive care or some special situations [43].

In our case, we treated the patient with glucocorticoids immediately since he presented with nephrotic syndrome. Indeed, recent KDIGO guidelines recommend using glucocorticoids in some patients with IgA nephropathy presented with nephrotic syndrome (including edema, both hypoalbuminemia and nephrotic-range proteinuria > 3.5 g/day) as this condition resembles podocytopathy such as minimal change disease [43]. In our case, AKI and the nephrotic syndrome were recovered after one week and two months of high-dose glucocorticoid treatment, respectively. Moreover, complete remission has been sustained with a low dose of glucocorticoids for the subsequent four months.

The causality between mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and IgA vasculitis is unclear. However, several pieces of evidence support possible mechanisms of how mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may induce autoimmunity. Evidence includes hypotheses related to the antigen-specific trigger by molecular mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and human tissue and to the antigen-nonspecific trigger by dysregulation of cytokine [1, 2, 44, 45]. In particular, IgA vasculitis with nephritis and IgA nephropathy share a four-hit hypothesis for pathogenesis; in this process, various cytokines are associated with autoimmunity [46]. Previous case reports have suggested that upper respiratory tract infection by SARS-CoV-2 can trigger IgA vasculitis [47,48,49,50]. IgA vasculitis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may share some occurrence mechanisms with IgA vasculitis in the COVID-19 infection setting. Further case reports and studies are required to understand the pathogenesis.

It is reasonable to advise patients to receive COVID-19 vaccination despite having prior or current IgA vasculitis, considering that most previous cases already reported were with a favorable prognosis. However, they need to be followed up more closely, especially if they are in remission and without any treatment.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- GN:

-

Glomerulonephritis

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration

- UPCR:

-

Urine protein/creatinine ratio

- RBCs:

-

Red blood cells

- WBCs:

-

White blood cells

- HPF:

-

High power field

References

Teijaro JR, Farber DL. COVID-19 vaccines: modes of immune activation and future challenges. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(4):195–7.

Sahin U, Muik A, Derhovanessian E, Vogler I, Kranz LM, Vormehr M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and T. Nature. 2020;586(7830):594–9.

Martinez Valenzuela L, Oliveras L, Gomà M, et al. Th1 cytokines signature in 2 cases of IgA nephropathy flare after mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: exploring the pathophysiology. Nephron. 2022;146(6):564–72. https://doi.org/10.1159/000524619.

Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–15.

Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–16.

Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, Tyner H, Yoon SK, Meece J, et al. Prevention and Attenuation of Covid-19 with the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(4):320–9.

Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, Miron O, Perchik S, Katz MA, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1412–23.

Li NL, Coates PT, Rovin BH. COVID-19 vaccination followed by activation of glomerular diseases: does association equal causation? Kidney Int. 2021;100(5):959–65.

Klomjit N, Alexander MP, Fervenza FC, Zoghby Z, Garg A, Hogan MC, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(12):2969–78.

Ma Y, Xu G. New-onset IgA nephropathy following COVID-19 vaccination [published online ahead of print, 2022 Aug 3] [published correction appears in QJM. 2022 Oct 22;:]. QJM. 2022;hcac185. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcac185.

Negrea L, Rovin BH. Gross hematuria following vaccination for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in 2 patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2021;99(6):1487.

Rahim SEG, Lin JT, Wang JC. A case of gross hematuria and IgA nephropathy flare-up following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Kidney Int. 2021;100(1):238.

Perrin P, Bassand X, Benotmane I, Bouvier N. Gross hematuria following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2021;100(2):466–8.

Tan HZ, Tan RY, Choo JCJ, Lim CC, Tan CS, Loh AHL, et al. Is COVID-19 vaccination unmasking glomerulonephritis? Kidney Int. 2021;100(2):469–71.

Kudose S, Friedmann P, Albajrami O, D’Agati VD. Histologic correlates of gross hematuria following Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2021;100(2):468–9.

Anderegg MA, Liu M, Saganas C, Montani M, Vogt B, Huynh-Do U, et al. De novo vasculitis after mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccination. Kidney Int. 2021;100(2):474–6.

Hanna C, Herrera Hernandez LP, Bu L, Kizilbash S, Najera L, Rheault MN, et al. IgA nephropathy presenting as macroscopic hematuria in 2 pediatric patients after receiving the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine. Kidney Int. 2021;100(3):705–6.

Plasse R, Nee R, Gao S, Olson S. Acute kidney injury with gross hematuria and IgA nephropathy after COVID-19 vaccination. Kidney Int. 2021;100(4):944–5.

Park K, Miyake S, Tai C, Tseng M, Andeen NK, Kung VL. “A case of Gross Hematuria and IgA Nephropathy Flare-Up following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination”. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(8):2246–7.

Abramson M, Mon-Wei Yu S, Campbell KN, Chung M, Salem F. IgA Nephropathy after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Kidney Med. 2021;3(5):860–3.

Horino T. IgA nephropathy flare-up following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. QJM. 2021;114(10):735–6.

Sugita K, Kaneko S, Hisada R, Harano M, Anno E, Hagiwara S, et al. Development of IgA vasculitis with severe glomerulonephritis after COVID-19 vaccination: a case report and literature review. CEN Case Rep. 2022;11(4):436–41.

Nakatani S, Mori K, Morioka F, Hirata C, Tsuda A, Uedono H, et al. New-onset kidney biopsy-proven IgA vasculitis after receiving mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine: case report. CEN Case Rep. 2022;11(3):358–62.

Horino T, Sawamura D, Inotani S, Ishihara M, Komori M, Ichii O. Newly diagnosed IgA nephropathy with gross haematuria following COVID-19 vaccination. QJM. 2022;115(1):28–9.

Park JS, Lee EY. Renal side effects of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2022;41(1):124–7.

Niel O, Florescu C. IgA nephropathy presenting as rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis following first dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37(2):461–2.

Abdel-Qader DH, Hazza Alkhatatbeh I, Hayajneh W, Annab H, Al Meslamani AZ, Elmusa RA. IgA nephropathy in a pediatric patient after receiving the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccine. 2022;40(18):2528–30.

Okada M, Kikuchi E, Nagasawa M, Oshiba A, Shimoda M. An adolescent girl diagnosed with IgA nephropathy following the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. CEN Case Rep. 2022;11(3):376–9.

Fujita Y, Yoshida K, Ichikawa D, Shibagaki Y, Yazawa M. Abrupt worsening of occult IgA nephropathy after the first dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. CEN Case Rep. 2022;11(3):302–8.

Lo WK, Chan KW. Gross haematuria after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in two patients with histological and clinical diagnosis of IgA nephropathy. Nephrol (Carlton). 2022;27(1):110–1.

Leong LC, Hong WZ, Khatri P. Reactivation of minimal change disease and IgA nephropathy after COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(3):569–70.

Lim JH, Kim MS, Kim YJ, Han MH, Jung HY, Choi JY, et al. New-onset kidney diseases after COVID-19 vaccination: a case series. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(2):302.

Srinivasan V, Geara AS, Han S, Hogan JJ, Coppock G. Need for symptom monitoring in IgA nephropathy patients post COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Nephrol. 2022;97(3):193–4.

Morisawa K, Honda M. Two patients presenting IgA nephropathy after COVID-19 vaccination during a follow-up for asymptomatic hematuria. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37(7):1695–6.

Nihei Y, Kishi M, Suzuki H, Koizumi A, Yoshida M, Hamaguchi S, et al. IgA Nephropathy with Gross Hematuria following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Intern Med. 2022;61(7):1033–7.

Yokote S, Ueda H, Shimizu A, Okabe M, Yamamoto K, Tsuboi N, et al. IgA nephropathy with glomerular capillary IgA deposition following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination: a report of three cases. CEN Case Rep. 2022;11(4):499–505.

Uchiyama Y, Fukasawa H, Ishino Y, Nakagami D, Kaneko M, Yasuda H, et al. Sibling cases of gross hematuria and newly diagnosed IgA nephropathy following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):216.

Watanabe S, Zheng S, Rashidi A. IgA nephropathy relapse following COVID-19 vaccination treated with corticosteroid therapy: case report. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):135.

Udagawa T, Motoyoshi Y. Macroscopic hematuria in two children with IgA nephropathy remission following Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37(7):1693–4.

Schaubschlager T, Rajora N, Diep S, Kirtek T, Cai Q, Hendricks AR, et al. De novo or recurrent glomerulonephritis and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of six cases from a single center. Clin Nephrol. 2022;97(5):289–97.

Barratt J, Feehally J. Treatment of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2006;69(11):1934–8.

Maritati F, Canzian A, Fenaroli P, Vaglio A. Adult-onset IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein): update on therapy. Presse Med. 2020;49(3):104035.

Group KDIGOKGDW. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int. 2021;100(4S):1–276.

Vojdani A, Kharrazian D. Potential antigenic cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and human tissue with a possible link to an increase in autoimmune diseases. Clin Immunol. 2020;217:108480.

Vojdani A, Vojdani E, Kharrazian D. Reaction of human monoclonal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 proteins with tissue antigens: implications for Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2020;11:617089.

Hastings MC, Rizk DV, Kiryluk K, Nelson R, Zahr RS, Novak J, et al. IgA vasculitis with nephritis: update of pathogenesis with clinical implications. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37(4):719–33.

Suso AS, Mon C, Oñate Alonso I, Galindo Romo K, Juarez RC, Ramírez CL, et al. IgA Vasculitis with Nephritis (Henoch-Schönlein Purpura) in a COVID-19 patient. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(11):2074–8.

Sandhu S, Chand S, Bhatnagar A, Dabas R, Bhat S, Kumar H, et al. Possible association between IgA vasculitis and COVID-19. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(1):e14551.

Barbetta L, Filocamo G, Passoni E, Boggio F, Folli C, Monzani V. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with renal and gastrointestinal involvement in course of COVID-19: a case report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(Suppl 129(2):191–2.

AlGhoozi DA, AlKhayyat HM. A child with Henoch-Schonlein purpura secondary to a COVID-19 infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(1):e239910.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There was no funding support for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SGK, JK, and IC were involved in diagnosis, management, and follow-up for this patient. SGK contributed to the conception of the work. JK, IC contributed to the interpretation of data. IC contributed to the acquisition of data and manuscript writing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient approved of publishing this manuscript and signed a written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, I., Kim, JK. & Kim, S.G. IgA vasculitis presenting as nephrotic syndrome following COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. BMC Nephrol 23, 403 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-03028-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-03028-7