Abstract

Background

Hypercalcemic hyperparathyroidism has been associated with poor outcomes after kidney transplantation (KTx). However, the clinical implications of normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism after KTx are unclear. This retrospective cohort study attempted to identify these implications.

Methods

Normocalcemic recipients who underwent KTx between 2000 and 2016 without a history of parathyroidectomy were included in the study. Those who lost their graft within 1 year posttransplant were excluded. Normocalcemia was defined as total serum calcium levels of 8.5–10.5 mg/dL, while hyperparathyroidism was defined as when intact parathyroid hormone levels exceeded 80 pg/mL. The patients were divided into two groups based on the presence of hyperparathyroidism 1 year after KTx. The primary outcome was the risk of graft loss.

Results

Among the 892 consecutive patients, 493 did not have hyperparathyroidism (HPT-free group), and 399 had normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism (NC-HPT group). Ninety-five patients lost their grafts. Death-censored graft survival after KTx was significantly lower in the NC-HPT group than in the HPT-free group (96.7% vs. 99.6% after 5 years, respectively, P < 0.001). Cox hazard analysis revealed that normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism was an independent risk factor for graft loss (P = 0.002; hazard ratio, 1.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.27–2.98).

Conclusions

Normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism 1 year after KTx was an independent risk factor for death-censored graft loss. Early intervention of elevated parathyroid hormone levels may lead to better graft outcomes, even without overt hypercalcemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is a frequent complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and increases the risk of mortality and various other complications [1]. Although successful kidney transplantation (KTx) can alleviate secondary hyperparathyroidism to some extent [2, 3], hyperparathyroidism often persists and adversely affects clinical outcomes despite improved kidney function [2,3,4,5,6]. Elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels promote bone resorption, calcium (Ca) reabsorption from the tubular tubes, and Ca absorption from the intestinal tract by increasing the production of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, often causing hypercalcemia [7]. Concerning the management of hyperparathyroidism after KTx, persistent hypercalcemia has been internationally recognized as the most common therapeutic indication [8,9,10,11], as hypercalcemia has been associated with poor outcomes. Egbuna et al. indicated in a retrospective study of 422 kidney transplant patients that hypercalcemia adversely affected mortality and graft prognosis [10]. Moore et al. also demonstrated the mortality risk of hypercalcemia in their study of 303 kidney transplant patients [11]. However, a high level of PTH alone is not generally a factor in making therapeutic decisions because it is not known whether high PTH levels without hypercalcemia may adversely affect kidney-graft function after KTx [12]. Therefore, this retrospective cohort study of 892 kidney transplant patients aimed to identify the impact of elevated PTH levels without hypercalcemia on kidney-graft outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports focusing on the clinical implications of high PTH levels without hypercalcemia after KTx.

Methods

Study design and subjects

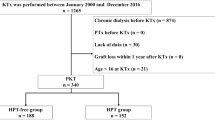

Consecutive patients who underwent KTx between January 2000 and December 2016 at the Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital (Nagoya, Japan) were included in the study. Data were collected on December 31, 2020. Our patient-exclusion criteria were as follows: those for whom data were lacking; those who had hypercalcemia or hypocalcemia within 1 year of KTx; those who were undergoing treatment with calcimimetics; those who had lost their kidney graft within 1 year of KTx; or those who were under 16 years of age at KTx. Furthermore, those who underwent parathyroidectomy (PTx) were also excluded because their PTH values were affected by the autografted parathyroid function. Hypercalcemia was defined as total serum Ca levels > 10.5 mg/dL. Hypocalcemia was defined as total serum Ca levels < 8.5 mg/dL. Normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism was defined as intact PTH levels of > 80 pg/mL without hypo/hypercalcemia 1 year after KTx. Intact PTH level has been reported to be ≤80 pg/mL in over 98% of healthy individuals irrespective of vitamin D status in both PTH assays used in this study [13].

Patients who met the inclusion criteria were divided into two groups based on the presence (or absence) of hyperparathyroidism: the HPT-free group, comprising patients without hyperparathyroidism and the NC-HPT group, comprising patients with normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism 1 year after successful KTx. Each patients’ sex, age, body mass index (BMI), dialysis vintage, number of HLA mismatches, positivity of donor-specific HLA antibody (DSA), laboratory data, mean blood pressure (MBP) 1 year after KTx, and graft survival were documented. The primary outcome was the risk of death-censored graft loss. Blood sample analyses were performed on all patients every month for 1 year following transplantation and every second month thereafter. The values of serum Ca and intact PTH obtained from blood samples 1 year after KTx were used for patient enrollment and classification. This study is reported according to Strengthening The Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology guidelines.

Measurements

Serum Ca and phosphorus (P) levels were measured using standard methods. Intact PTH levels were measured using second-generation immunoassays: an electrochemical luminescence immunoassay (SRL, Tokyo, Japan, www.srl-group.co.jp, reference range [10–65 pg/mL]), or an enzyme immunoassay (TOSOH Company, Tokyo, Japan, www.tosoh.co.jp, reference range [9–80 pg/mL]). When serum albumin values were < 4.0 g/dL, all serum Ca values were corrected with serum albumin values as follows [14].

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was evaluated using the creatinine equation provided by the Japanese Society of Nephrology [15].

Immunosuppression

According to protocols conducted at the Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital, the main immunosuppressive regimens were calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine or tacrolimus), mycophenolic acid, mizoribine, everolimus, and glucocorticoids. Basiliximab was used as induction therapy. Furthermore, rituximab administration or splenectomy was used as induction therapy in anti-donor antibody-positive patients with KTx, except in those with low antibody titers.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to analyze nominal variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables. All results are presented as median (interquartile range) because of their non-normal distribution, confirmed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the correlations among the variables (Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM 1)). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and logrank tests were used to estimate the graft survival rates. The Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to evaluate the risk of death-censored graft loss. Donor age [16], BMI [17], diabetes mellitus [18], preformed DSA [19], ABO blood type incompatibility [20], serum P [21], and eGFR [22] 1 year post KTx were included as covariates in the multivariate analysis; these factors have been reported as renal prognostic factors after KTx in previous studies [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. To reduce selection bias and potential confounding effects, propensity score (PS)-based methods were also employed. A logistic regression model involving 11 covariates was used to derive PSs. These covariates included eight continuous variables (recipient age, BMI, dialysis vintage, donor age, serum P, serum Ca, eGFR, and MBP 1 year post KTx) and three nominal variables (ABO blood type incompatibility, diabetes mellitus, and preformed DSA). Inverse probability of treatment weighting for NC-HPT was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) for death-censored graft loss by the Cox proportional hazards model (ESM 2). In addition, PS matching in a 1:1 raio between the NC-HPT and HPT-free groups was also performed to confirm the robustness of the results of other analyses (ESM 3, ESM 4). The crude and multivariable-adjusted risk for death-censored graft loss with intact PTH levels categorized by quartiles were also examined. SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and EZR version 1.40 [23] were used for statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

A total of 892 patients met the inclusion criteria for the study (median observation period: 129 [interquartile range, 93–174] months). Of the 892 patients, 493 were assigned to the HPT-free group, and 399 were assigned to the NC-HPT group (Fig. 1). The number and proportion of patients in the NC-HPT group tended to increase over the years (Fig. 2). The intact PTH levels of the NC-HPT group were consistently higher than those of the HPT-free group from the time of KTx to 1 year after KTx (ESM 5). Patient baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were significant differences between the HPT-free and the NC-HPT groups in recipient age, donor age, BMI, dialysis vintage, serum Ca, serum P, intact PTH, eGFR and MBP 1 year after KTx. Other characteristics did not differ between the two groups (Table 1). Although no patients were treated with calcimimetics during the follow-up period, oral vitamin D supplementation was introduced in 9.9% (49/493) of patients in the HPT-free group 97 (65–133) months after KTx, and 11.3% (45/399) of patients in the NC-HPT group 82 (45–114) months after KTx, mainly for the treatment of osteoporosis (P = 0.591). There was a weak correlation between intact PTH and age, dialysis vintage, BMI, serum Ca, serum P, and eGFR, with an absolute correlation coefficient of less than 0.2 (ESM 1).

Graft survival

Graft loss was observed in 95 patients, with a more frequent occurrence in the NC-HPT group than in the HPT-free group (13.3% vs 8.5%, respectively, P = 0.022) despite the shorter follow-up period in the NC-HPT group (116 months vs 146 months, respectively, P < 0.001) (Table 1). The death-censored graft survival in the NC-HPT group was significantly lower than that in the HPT-free group (96.7% vs. 99.6% at 5 years and 88.5% vs 95.7% at 10 years, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). Even after PS matching of 306 recipients from each group, death-censored graft survival of NC-HPT recipients was still inferior to that of HPT-free recipients (98.7% vs 99.5% at 5 years, and 89.3% vs 94.9% at 10 years, P = 0.007) (Fig. 3B). The proportion of graft loss due to chronic allograft nephropathy was significantly higher in the NC-HPT group than in the HPT-free group (5.8% vs. 1.9%, P = 0.002) (Table 1).

Risk of death-censored graft loss

The univariate Cox proportional hazards revealed that the independent risk factors for death-censored graft loss were donor age (P = 0.020; HR, 1.025; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.004–1.048), BMI (P = 0.005; HR, 1.075; 95% CI, 1.022–1.130), diabetes mellitus (P = 0.028; HR, 1.719; 95% CI, 1.061–2.785), DSA positivity (P = 0.003; HR, 3.117; 95% CI, 1.485–6.546), serum P 1 year post-KTx (P < 0.001; HR, 1.705; 95% CI, 1.298–2.241), eGFR 1 year post-KTx (P < 0.001; HR, 0.953; 95% CI, 0.935–0.972), and normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism (P < 0.001; HR, 2.290; 95% CI, 1.518–3.457) (Table 2). The multivariate Cox proportional hazards model confirmed a significantly increased risk of death-censored graft loss in normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism (P = 0.002; HR, 1.944; 95% CI, 1.268–2.980) (Table 2). In addition, the Cox proportional hazards model adjusted by PS-based methods also revealed significantly higher risk of death-censored graft loss in the NC-HPT group than in the HPT-free group (Table 3). Figure 4 shows crude (unadjusted) and multivariable-adjusted HRs for death-censored graft loss with categories of intact PTH levels at 1 year after KTx. There was a trend to an increase in the multivariate-adjusted HR of death-censored graft loss with intact PTH levels of 77–100 pg/mL (P = 0.067, HR, 1.688; 95% CI: 0.963–2.958) and > 100 pg/mL (P = 0.020, HR, 2.017; 95% CI: 1.117–3.644) (Fig. 4).

HRs for graft loss according to categories of PTH using Cox proportional hazard model. The multivariable-adjusted analysis included donor age, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, preformed donor-specific HLA antibody, ABO blood type incompatible KTx, phosphorus, and eGFR at one year post-KTx. *P < 0.05. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; PTH, parathyroid hormone; KTx, kidney transplantation

Discussion

The multivariate analyses in this study demonstrated that BMI, DSA, serum P, and eGFR 1 year post-KTx were risk factors for graft loss, which is consistent with previous reports [17, 19, 21, 22]. Even with adjustment for these risk factors, normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism 1 year after KTx was shown to be an independent risk factor for death-censored graft loss. In addition, the multivariable-adjusted HRs of graft loss with category levels of PTH showed that graft prognosis could become worse as PTH values increase. The increasing trend of normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism shown in this study may be due to an increase of elderly patients or a drastic decrease of pretransplant PTx accompanied by the recent developments of medical treatments [24]. Taken together with its increasing tendency, normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism after KTx could be a non-negligible disease entity. Our results are consistent with other studies indicating that PTH may be a risk factor for graft loss [4, 25]. These results suggest the need for active management of elevated PTH levels after KTx, even in the absence of hypercalcemia. Furthermore, for the prevention of post-KTx hyperparathyroidism, active intervention for elevated PTH prior to KTx should be considered.

Since GFR reduction is a direct cause of PTH elevation, it is difficult to determine whether high PTH after KTx is mainly due to low GFR or to parathyroid gland hyperplasia [26]. In addition, hyperparathyroidism is also associated with hypertension [27]. Therefore, although adjusted by mulitivariate analysis and PS-based methods in this study, the inferior graft survival in the NC-HPT group may have been influenced by low GFR or hypertension. However, there are several possible mechanisms by which elevated PTH levels can worsen graft outcomes. Normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism in non-CKD patients reportedly increases nephrolithiasis [28,29,30,31] and cardiovascular risk [32,33,34]. Furthermore, some observational studies in cases of secondary hyperparathyroidism have demonstrated the association of PTH with renal anemia [35] or immunodeficiency [36]. In addition, it has been recently reported that PTH increases energy consumption by transforming adipocytes to brown adipocytes, leading to cachexia-like pathology seen in patients with malignancy [37]. More importantly, PTH can induce various effects by promoting the secretion of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) [38]. FGF23 is a humoral factor produced by osteocytes and has been recognized as a significant predictor of life prognosis in patients undergoing dialysis [39], in whom it can induce cardiac hypertrophy [40], renal anemia [41], immunodeficiency [42], and chronic inflammation [43]. Additionally, both PTH and FGF23 increase pathological fibrosis in CKD [44], a condition known to adversely affect kidney grafts. The various pathologies mentioned above may explain the association between normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism and inferior graft outcome in the present study.

The optimal management of normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism in kidney transplant patients is controversial due to a lack of consensus. However, aggressive treatment for elevated PTH after KTx may improve clinical outcomes, as several reports have demonstrated that therapeutic intervention for normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism in non-CKD patients can reduce complication risks, including bone lesions [45, 46], nephrolithiasis [47, 48], cardiovascular disease [34], and reduced quality of life [49].

Although the “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” guidelines recommend active vitamin D and bisphosphonates as medical treatments for hyperparathyroidism in the first year after KTx, these treatments are often difficult to implement because of concerns about hypercalcemia, insufficient kidney function, and/or low bone turnover [50]. Therefore, interventions and therapeutic options for hyperparathyroidism with normocalcemia should be tailored to individual cases in actual clinical practice. PTx or medical treatments such as calcimimetics, vitamin D, or bisphosphonate should be prescribed according to underlying CKD conditions, including levels of Ca and PTH, degree of enlargement of parathyroid glands, kidney function, bone loss, and cardiovascular risk in the patient.

This study has several limitations, most of which are due to its retrospective nature, its confinement to a single center, the inherent possibility of unmeasured confounders, selection bias, and absence of data regarding endogenic vitamin D levels, FGF23, other bone biomarkers, and renal lithiasis. Hence, further studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to validate the findings of this study.

Conclusions

Hyperparathyroidism 1 year after KTx was found to be an independent risk factor for death-censored graft loss, even without overt hypercalcemia. Early management and intervention of elevated PTH levels may contribute to better graft outcomes after kidney transplantation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DSA:

-

Donor-specific HLA antibody

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FGF23:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 23

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IPTW:

-

Inverse probability of treatment weighting

- KTx:

-

Kidney transplantation

- MBP:

-

Mean blood pressure

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- PTH:

-

Parathyroid hormone

- PS:

-

Propensity score

- PTx:

-

Parathyroidectomy

References

Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, Ofsthun N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2208–18.

Reinhardt W, Bartelworth H, Jockenhövel F, Schmidt-Gayk H, Witzke O, Wagner K, et al. Sequential changes of biochemical bone parameters after kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:436–42.

Lee HH, Kim AJ, Ro H, Jung JY, Chang JH, Chung W, et al. Sequential changes of vitamin D level and parathyroid hormone after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:897–9.

Pihlstrøm H, Dahle DO, Mjøen G, Pilz S, März W, Abedini S, et al. Increased risk of all-cause mortality and renal graft loss in stable renal transplant recipients with hyperparathyroidism. Transplantation. 2015;99:351–9.

Araujo MJCLN, Ramalho JAM, Elias RM, Jorgetti V, Nahas W, Custodio M, et al. Persistent hyperparathyroidism as a risk factor for long-term graft failure: the need to discuss indication for parathyroidectomy. Surgery. 2018;163:1144–50.

Lou I, Foley D, Odorico SK, Leverson G, Schneider DF, Sippel R, et al. How well does renal transplantation cure hyperparathyroidism? Ann Surg. 2015;262:653–9.

Talmage RV, Mobley HT. Calcium homeostasis: reassessment of the actions of parathyroid hormone. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2008;156:1–8.

Tang JA, Friedman J, Hwang MS, Salapatas AM, Bonzelaar LB, Friedman M. Parathyroidectomy for tertiary hyperparathyroidism: a systematic review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38:630–5.

Fukagawa M, Yokoyama K, Koiwa F, Taniguchi M, Shoji T, Kazama JJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder. Ther Apher Dial. 2013;17:247–88.

Egbuna OI, Taylor JG, Bushinsky DA, Zand MS. Elevated calcium phosphate product after renal transplantation is a risk factor for graft failure. Clin Transpl. 2007;21:558–66.

Moore J, Tomson CR, Tessa Savage M, Borrows R, Ferro CJ. Serum phosphate and calcium concentrations are associated with reduced patient survival following kidney transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2011;25:406–16.

Tominaga Y. Surgical Management of Secondary and Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism. In: Randolph G, editor. Surgery of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2020. p. 564–75.

Yalla N, Bobba G, Guo G, Stankiewicz A, Ostlund R. Parathyroid hormone reference ranges in healthy individuals classified by vitamin d status. J Endocrinol Investig. 2019;42:1353–60.

Anonymous. Correcting the calcium. Br Med J. 1977;1:598.

Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, et al. Collaborators developing the Japanese equation for estimated GFR. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982–92.

Iordanous Y, Seymour N, Young A, Johnson J, Iansavichus AV, Cuerden MS, et al. Recipient outcomes for expanded criteria living kidney donors: the disconnect between current evidence and practice. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1558–73.

Liese J, Bottner N, Büttner S, Reinisch A, Woeste G, Wortmann M, et al. Influence of the recipient body mass index on the outcomes after kidney transplantation. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2018;403:73–82.

Lim WH, Wong G, Pilmore HL, McDonald S, Chadban SJ. Long-term outcomes of kidney transplantation in people with type 2 diabetes a population cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:26–33.

Gloor JM, Winters JL, Cornell LD, Fix LA, DeGoey SR, Knauer RM, et al. Baseline donor-specific antibody levels and outcomes in positive crossmatch kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:582–9.

Scurt FG, Ewert L, Mertens PR, Haller H, Schmidt BM, Chatzikyrkou C. Clinical outcomes after ABO-incompatible renal transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;393:2059–72.

Merhi B, Shireman T, Carpenter MA, Kusek JW, Jacques P, Pfeffer M, et al. Serum phosphorus and risk of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, or graft failure in kidney transplant recipients an ancillary study of the FAVORIT trial cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70:377–85.

Salvadori M, Rosati A, Bock A, Chapman J, Dussol B, Fritsche L, et al. Estimated one-year glomerular filtration rate is the best predictor of long-term graft function following renal transplant. Transplantation. 2006;81:202–6.

Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–8.

Tominaga Y, Kakuta T, Yasunaga C, Makamura M, Kadokura Y, Tahara H. Evaluation of parathyroidectomy for secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism by the parathyroid surgeons’ society of Japan. Ther Apher Dial. 2016;20:6–11.

Bleskestad IH, Bergrem H, Leivestad T, Hartmann A, Gøransson LG. Parathyroid hormone and clinical outcome in kidney transplant patients with optimal transplant function. Clin Transpl. 2014;28:479–86.

Nakano C, Hamano T, Fujii N, Matsui I, Tomida K, Mikami S, et al. Combined use of vitamin D status and FGF23 for risk stratification of renal outcome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:810–9.

Simeoni M, Perna AF, Fuiano G. Secondary hyperparathyroidism and hypertension: an intriguing couple. J Clin Med. 2020;9:629.

Marques TF, Vasconcelos R, Diniz E, Rêgo D, Griz L, Bandeira F. Normocalcemic primary hyperparathyroidism in clinical practice: an indolent condition or a silent threat? Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2011;55:314–7.

Šiprová H, Fryšák Z, Souček M. Primary hyperparathyroidism, with a focus on management of the normocalcemic form: to treat or not to treat? Endocr Pract. 2016;22:294–301.

Tordjman KM, Greenman Y, Osher E, Shenkerman G, Stern N. Characterization of normocalcemic primary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Med. 2004;117:861–3.

Amaral LM, Queiroz DC, Marques TF, Mendes M, Bandeira F. Normocalcemic versus hypercalcemic primary hyperparathyroidism: more stone than bone? J Osteoporos. 2012;2012:128352.

Pepe J, Cipriani C, Sonato C, Raimo O, Biamonte F, Minisola S. Cardiovascular manifestations of primary hyperparathyroidism: a narrative review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177:R297–308.

Koubaity O, Mandry D, Nguyen-Thi P-L, Kobayashi T, Iwaki M, Honda Y, et al. Coronary artery disease is more severe in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery. 2020;167:149–54.

Beysel S, Caliskan M, Kizilgul M, Apaydin M, Kan S, Ozbek M, et al. Parathyroidectomy improves cardiovascular risk factors in normocalcemic and hypercalcemic primary hyperparathyroidism. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19:106.

Trunzo JA, McHenry CR, Schulak JA, Wilhelm SM. Effect of parathyroidectomy on anemia and erythropoietin dosing in end-stage renal disease patients with hyperparathyroidism. Surgery. 2008;144:915–9.

Yasunaga C, Nakamoto M, Matsuo K, Nishihara G, Yoshida T, Goya T. Effects of a parathyroidectomy on the immune system and nutritional condition in chronic dialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Surg. 1999;178:332–6.

Kir S, Komaba H, Garcia AP, Economopoulos KP, Liu W, Lanske B, et al. PTH/PTHrP receptor mediates cachexia in models of kidney failure and cancer. Cell Metab. 2016;23:315–23.

Meir T, Durlacher K, Pan Z, Amir G, Richards WG, Silver J, et al. Parathyroid hormone activates the orphan nuclear receptor Nurr1 to induce FGF23 transcription. Kidney Int. 2014;86:1106–15.

Gutiérrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–92.

Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B, Hu MC, Sloan A, Isakova T, et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4393–408.

Coe LM, Madathil SV, Casu C, Lanske B, Rivella S, Sitara D. FGF-23 is a negative regulator of prenatal and postnatal erythropoiesis. J Bio Chem. 2014;289:9795–810.

Rossaint J, Oehmichen J, Van Aken H, Reuter S, Pavenstädt HJ, Meersch M, et al. FGF23 signaling impairs neutrophil recruitment and host defense during CKD. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:962–74.

Singh S, Grabner A, Yanucil C, Schramm K, Czaya B, Krick S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 directly targets hepatocytes to promote inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016;90:985–96.

Panizo S, Martínez-Arias L, Alonso-Montes C, Cannata P, Martín-Carro B, Fernández-Martín JL, et al. Fibrosis in chronic kidney disease: pathogenesis and consequences. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:408.

Sho S, Kuo EJ, Chen AC, Li N, Yeh MW, Livhits MJ. Biochemical and skeletal outcomes of parathyroidectomy for normocalcemic (incipient) primary hyperparathyroidism. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:539–46.

Koumakis E, Souberbielle J-C, Sarfati E, Meunier M, Maury E, Gallimard E, et al. Bone mineral density evolution after successful parathyroidectomy in patients with normocalcemic primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3213–20.

Traini E, Bellantone R, Tempera SE, Russo S, De Crea C, Lombardi CP, et al. Is parathyroidectomy safe and effective in patients with normocalcemic primary hyperparathyroidism? Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. 2018;403:317–23.

Grimelius L, Ejerblad S, Johansson H. Parathyroid adenomas and glands in normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism. A light microscopic study. Am J Pathol. 1976;83:475–84.

Bannani S, Christou N, Guérin C, Hamy A, Sebag F, Mathonnet M, et al. Effect of parathyroidectomy on quality of life and non-specific symptoms in normocalcaemic primary hyperparathyroidism. Br J Surg. 2018;105:223–9.

Chapman JR. The KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2010;89:644–5.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Momo Kamiya and Taiki Yamanaka of the Division of Medical Statistics at Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital for valuable data collection and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This study received no funding or financial support from the industry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Manabu Okada: conception, design, and drafting the article; Yoshihiro Tominaga and Tetsuhiko Sato: conception and drafting the article; Toshihide Tomosugi, Kenta Futamura, Takahisa Hiramitsu, Toshihiro Ichimori, and Norihiko Goto: acquisition and interpretation of data; Shunji Narumi, Takaaki Kobayashi, and Kazuharu Uchida: critical revision of the article for important intellectual content; Yoshihiko Watarai: giving final approval of the manuscript to be published. All authors consented to the publication of this study. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital (approval number: 1409) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The informed consent waiver was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital. Details regarding the study and opt-out were provided in full on our institutional website.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Okada, M., Tominaga, Y., Sato, T. et al. Elevated parathyroid hormone one year after kidney transplantation is an independent risk factor for graft loss even without hypercalcemia. BMC Nephrol 23, 212 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-02840-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-02840-5