Abstract

Background

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disorder and can affect any organ; however, ureteric involvement is extremely rare with only four cases reported in the literature to date, all of which were diagnosed with surgical ureteral resection including a nephroureterectomy. This study reports the first case of ureteric sarcoidosis controlled with medical therapy where a differential diagnosis was performed based on the diagnostic clue of hypercalcemia. A definitive diagnosis was established without surgical resection of the ureter.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old man presented with anorexia and weight loss. Blood tests showed renal dysfunction and hypercalcemia. Computed tomography revealed left hydronephrosis associated with left lower ureteral wall thickening, which showed high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Similarly, we detected a bladder tumor on cystoscopy, and a 2-cm-long stenosis was revealed by retrograde ureterography; therefore, ureteral cancer was suspected. Meanwhile, considering the clinical implication of hypercalcemia, a differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established based on elevated levels of sarcoidosis markers. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation in the left lower ureter, skin, and muscles, suggestive of ureteric sarcoidosis with systemic sarcoid nodules. For a definitive diagnosis, transurethral resection of the bladder tumor and ureteroscopic biopsy were performed. Histopathological examination revealed ureteric sarcoidosis with bladder urothelial carcinoma. Following an oral administration of prednisolone, hypercalcemia instantly resolved, the renal function immediately improved, and the left ureteral lesion showed complete resolution with no recurrence.

Conclusions

In this case, the co-occurrence of ureteral lesion with bladder tumor evoked a diagnosis of ureteral cancer. However, considering a case of ureteral lesion complicated with hypercalcemia, assessment for differential diagnosis was performed based on the calcium metabolism and sarcoidosis markers. In cases of suspected ureteric sarcoidosis from the assessment, pathological evaluation with ureteroscopic biopsy should be performed to avoid nephroureterectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disorder characterized by the formation of non-caseating granulomas and can affect any organ [1]. However, ureteric involvement is extremely rare, with only four cases reported in the literature to date, all of which were diagnosed with surgical ureteral resection including a nephroureterectomy [2,3,4,5]. To our knowledge, this is the first case of ureteric sarcoidosis controlled with medical therapy, where differential diagnosis was performed based on the diagnostic clue of hypercalcemia, and a definitive diagnosis was established without surgical resection.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old man with no medical history or comorbidities presented with anorexia and weight loss (from 59.4 kg before admission to 55.9 kg on admission). No findings were observed on physical examination. Blood tests showed renal dysfunction (creatinine, 2.27 mg/dL) and hypercalcemia (total serum calcium corrected for albumin, 12.2 mg/dL). A urine test revealed hypercalciuria without proteinuria (Table 1).

The hypercalcemia was treated with the administration of elcatonin and normal saline infusion for fluid replacement. Computed tomography (CT) revealed left hydronephrosis associated with left lower ureteral wall thickening, which showed high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (Figs. 1a, b, 4a). Although the voided urinary cytology result was negative, a 5-mm papillary pedunculated tumor was detected on the left lateral wall of the bladder on cystoscopy; in addition, a 2-cm-long stenosis in the left lower ureter was revealed by retrograde ureterography. Therefore, a ureteral cancerous lesion was suspected.

CT, MRI, and FDG-PET findings for the left lower ureteral lesion and whole-body FDG accumulation. a. Abdominal plain CT shows left hydronephrosis associated with left lower ureteral wall thickening (white arrow). b Diffusion-weighted MRI shows high signal intensity for the ureteral lesion (white arrow). c FDG-PET reveals FDG accumulation in the left lower ureter (white arrow), skin, and muscles (white arrowhead). d. The black striae formed by FDG accumulation represent sarcoid nodules in the skin and muscles. The black arrows illustrate representative sites of the sarcoid nodules. CT: computed tomography, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, FDG: fluorodeoxyglucose, FDG-PET: fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

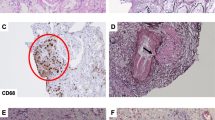

Meanwhile, considering the clinical implication of hypercalcemia, a differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established based on elevated levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2D3, 151.0 ng/L, normal range: 20.0–60.0 ng/L) and sarcoidosis markers: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE, 39.7 U/L, normal range: 7.0–25.0 U/L), lysozyme (37.9 mg/L, normal range: 5.0–10.2 mg/L), and soluble interleukin-2 receptor (SIL-2R, 3190 U/ml, normal range: 145–519 U/ml). Neither 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), parathyroid hormone (PTH), nor parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) was elevated: levels of 25(OH)D, PTH and PTHrP were 23.3 (normal range: > 20.0 ng/mL) ng/mL, 15.0 (normal range: 15.0–65.0 pg/mL) pg/mL and < 1.1 (normal range: < 1.1 pmol/L) pmol/L, respectively (Table 1). Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) showed FDG accumulation not only in the left lower ureter but also in the skin and muscles, suggestive of ureteric sarcoidosis with systemic sarcoid nodules (Fig. 1c, d). Among the sites of FDG accumulation in the skin and muscles, the nodules were palpated at the right side chest, right thigh, and right lumbar region. For a definitive diagnosis, transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) and ureteroscopy were performed. Histopathological examination of TURBT specimens revealed pTa high-grade bladder urothelial carcinoma, with ureteroscopic evaluation showing circumferential stenosis in the left lower ureter without an obvious mass lesion. Furthermore, we selectively collected samples of left ureteral urine for cytology, performed a biopsy at the stenosis site, and subsequently placed a double -J stent (DJS). Left hydronephrosis resolved after the alleviation of the left upper urinary tract obstruction by the DJS; however, no improvement in renal function was observed. The ureteral urinary cytology result was negative, and the histopathological examination of ureteral biopsy specimens revealed non-caseating granulomas without cancerous tissue (Fig. 2), thereby confirming the diagnosis of ureteric sarcoidosis. Hypercalcemia instantly resolved, and the renal function immediately improved following an oral administration of prednisolone (PSL) (Fig. 3). Moreover, hypercalciuria diminished, and both 1,25-(OH)2D3 and sarcoidosis markers were normalized (Table 1). Eighteen days after the initiation of PSL treatment, CT showed complete resolution of the left ureteral lesion (Fig. 4b), and subsequently, the DJS was removed. Sixty-three days after the initiation of PSL, CT revealed no recurrence of the left ureteral lesion (Fig. 4c). To date, there has been no recurrence of the left ureteral lesion, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction in the patient who is presently on tapered PSL dose.

CT findings for the ureteral lesion. The white arrows indicate the left ureteral lesion. a. Before administration of PSL. b. Eighteen days after the initiation of PSL, complete resolution of the left ureteral lesion was recognized. c. Sixty-three days after the initiation of PSL, there was no recurrence after the removal of DJS. CT: computed tomography, PSL: prednisolone, DJS: double J stent

Discussion and conclusions

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology, characterized by the formation of non-caseating granulomas. Exaggerated immune response to an undefined antigen (e.g., environmental factors, microbes, or degraded antigen) has been implicated as a potential cause of sarcoidosis [1]. Sarcoidosis can affect any organ: the most commonly affected organ is the lungs [1]. In addition, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, which was not recognized in the present case, is the most common radiological finding in sarcoidosis [6]. On the contrary, ureteric involvement is extremely rare, and diagnosis of ureteric sarcoidosis before surgical resection is challenging [2,3,4,5]. In this case, clarifying the cause of hypercalcemia served as a helpful clue to the diagnosis of ureteric sarcoidosis without the need for surgical ureteral resection.

Calcium metabolism disorder, characterized by hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, which were recognized in this case, is a clinical feature in sarcoidosis. Hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria occur in approximately 5% and 40–62% of sarcoidosis patients, respectively [7]. An increase in the production of 1,25-(OH)2D3 by non-caseating granulomas has been implicated in calcium metabolism disorder. An elevated level of 1,25-(OH)2D3 enhances intestinal calcium absorption and promotes osteoclastic activity and bone resorption, resulting in hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria [8,9,10].

Calcium metabolism disorder is the most important cause of renal dysfunction. Several different mechanisms, including vasoconstriction of arterioles, acute tubular necrosis, impairment of urinary concentrating ability caused by decreased sensitivity to antidiuretic hormone, and nephrocalcinosis, have been implicated in renal dysfunction [10]. In the present case, improvement in renal function was not observed after the resolution of the left upper urinary tract obstruction with DJS placement; however, renal function improved after amelioration of hypercalcemia by PSL administration. These findings suggested that sarcoidosis-related calcium metabolism disorder was the main cause of renal dysfunction, although renal biopsy was not performed.

The present case met the diagnostic criteria of sarcoidosis: a compatible clinical and/or radiological image, histopathologic evidence of non-caseating granulomas, and exclusion of other diseases with similar findings, such as infections or malignancy [11]. The indications for the treatment of sarcoidosis have been shown to be disease-related symptoms in patients or organ dysfunction [12]. In the present case, since the patient had anorexia, weight loss and renal dysfunction, which were consistent with the indications for treatment, PSL, a corticosteroid, was orally administered. Oral corticosteroids are considered the first-line treatment in the management of sarcoidosis, and the effectiveness of PSL has been reported in sarcoidosis-related hypercalcemia [7, 10, 13]. In fact, PSL was an effective treatment for ureteric sarcoidosis with hypercalcemia in this case.

In the present case, the co-occurrence of ureteral lesion with bladder tumor evoked a diagnosis of ureteral cancer. Meanwhile, the clinical manifestation of hypercalcemia served as a clue to the differential diagnosis of ureteric sarcoidosis through the elevated levels of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and sarcoidosis markers (ACE, lysozyme, and SIL-2R). However, it should be noted that urothelial carcinoma is rarely complicated by hypercalcemia as paraneoplastic syndrome [14,15,16]. In this case, no increase was observed in the PTHrP level, which has been most commonly associated with paraneoplastic hypercalcemia in various malignancies [15]. In ureteral cancer, 1,25-(OH)2D3 is similarly reported to be one of the inducers of paraneoplastic hypercalcemia [16]. Therefore, the measurement of sarcoidosis markers in addition to that of calcium metabolism markers, such as PTHrP and 1,25-(OH)2D3, would be needed to clarify the cause of hypercalcemia. Finally, ureteroscopy is a useful tool, which can facilitate more precise pathological diagnosis [17]. In the present case, ureteroscopic biopsy contributed to the definitive diagnosis of ureteric sarcoidosis, avoiding surgical resection.

In conclusion, in the cases of ureteral lesions complicated with hypercalcemia, assessments for differential diagnosis based not only on calcium metabolism markers but also on sarcoidosis markers should be performed as a first step. This can help decide whether subsequent examinations for ureteric sarcoidosis are necessary. In the event ureteric sarcoidosis is suspected after the initial assessments, pathological evaluation with ureteroscopic biopsy should be performed, as ureteric sarcoidosis with hypercalcemia can be controlled with medical therapy, thus avoiding nephroureterectomy.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- 1,25-(OH)2D3 :

-

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- SIL-2R:

-

Soluble interleukin-2 receptor

- 25(OH)D:

-

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- PTH:

-

Parathyroid hormone

- PTHrP:

-

Parathyroid hormone-related peptide

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- FDG-PET:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- TURBT:

-

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor

- DJS:

-

Double J stent

- PSL:

-

Prednisolone

References

Soto-Gomez N, Peters JI, Nambiar AM. Diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:840–8.

Hashimoto Y, Kudoh S, Yamamoto H, Hatakeyama S, Yoneyama T, Koie T, et al. Sarcoidosis of the ureter. Urology. 2012;79:e81–2.

Kalia V, Vishal K, Gill JS, Gill A. Ureteric sarcoidosis-a rare entity. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:e247–8.

Mariano RT, Sussman SK. Sarcoidosis of the ureter. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1431.

Perimenis P, Athanasopoulos A, Barbalias G. Sarcoidosis of the ureter. Eur Urol. 1990;18:307–8.

Park HJ, Jung JI, Chung MH, Song SW, Kim HL, Balk JH, et al. Typical and atypical manifestations of intrathoracic sarcoidosis. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:623–31.

Conron M, Young C, Beynon HL. Calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis and its clinical implication. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:707–13.

Kato Y, Taniguchi N, Okuyama M, Kakizaki H. Three cases of urolithiasis associated with sarcoidosis: a review of Japanese cases. Int J Urol. 2007;14:954–6.

Hishida E, Masuda T, Akimoto T, Sato R, Wakabayashi N, Miki A, et al. Renal failure found during the follow-up of sarcoidosis: the relevance of a delay in the diagnosis of concurrent hypercalcemia. Intern Med. 2016;55:1893–8.

Hilderson I, Van Laecke S, Wauters A, Donck J. Treatment of renal sarcoidosis: is there a guideline? Overview of the different treatment options. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:1841–7.

Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736–55.

Prasse A. The diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment of sarcoidosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:565–74.

Grutters JC, Van den Bosch JM. Corticosteroid treatment in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:627–36.

Sullivan EO, Plant W. A rare complication of transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis: parathyroid hormone-related peptide-induced by hypercalcemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-202796.

Patel AB, Wilson L, Blick C, Meffan P. Paraneoplastic hypercalcemia associated with TCC of bladder. Sci World J. 2004;4:1069–70.

Asao K, McHugh JB, Miller DC, Esfandiari NH. Hypercalcemia in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2013;2013:470890. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/470890.

Rouprêt M, Babjuk M, Compérat E, Zigeuner R, Sylvester RJ, Burger M, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on upper urinary tract Urothelial carcinoma: 2017 update. Eur Urol. 2018;73:111–22.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Drafting of the manuscript: MH. Revision of the manuscript: KH, SN, KO, KS, NS, and AY. Supervision: SU, and TO. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors obtained written informed consent from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashida, M., Yano, A., Hagiwara, K. et al. Relevance of concurrent hypercalcemia in ureteric sarcoidosis complicated with bladder urothelial carcinoma: a case report. BMC Nephrol 21, 235 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01893-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01893-8