Abstract

Background

Initial presentation of peritoneal dialysis associated infectious peritonitis can be clinically indistinguishable from Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) and both may demonstrate a cloudy dialysate. Empiric treatment of the former entails use of 3rd-generation cephalosporins, which could worsen CDI. We present a logical management approach of this clinical scenario providing examples of two cases with CDI associated peritonitis of varying severity where the initial picture was concerning for peritonitis and treatment for CDI resulted in successful cure.

Case presentation

A 73-year-old male with ESRD managed with PD presented with fever, abdominal pain, leukocytosis and significant diarrhea. Cell count of the peritoneal dialysis effluent revealed 1050 WBCs/mm3 with 71% neutrophils. C. difficile PCR on the stool was positive. Patient was started on intra-peritoneal (IP) cefepime and vancomycin for treatment of the peritonitis and intravenous (IV) metronidazole and oral vancomycin for treatment of the C. difficile colitis but worsened. PD fluid culture showed no growth. He responded well to IV tigecycline, oral vancomycin and vancomycin enemas. Similarly, a 55-year-old male with ESRD with PD developed acute diarrhea and on the third day noted a cloudy effluent from his dialysis catheter. PD fluid analysis showed 1450 WBCs/mm3 with 49% neutrophils. IP cefepime and vancomycin were initiated. CT of the abdomen showed rectosigmoid colitis. C. difficile PCR on the stool was positive. IP cefepime and vancomycin were promptly discontinued. Treatment with oral vancomycin 125 mg every six hours and IV Tigecycline was initiated. PD fluid culture produced no growth. PD catheter was retained.

Conclusions

In patients presenting with diarrhea with risk factors for CDI, traditional empiric treatment of PD peritonitis may need to be reexamined as they could have detrimental effects on CDI course and patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) peritonitis is a dominant cause of PD failure among patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD). These individuals present largely with a gastrointestinal (GI) syndrome with or without accompanying systemic features e.g. fever; and a cloudy PD effluent secondary to elevated white blood cell (WBC) counts with predominance of neutrophils. Current management guidelines recommend early institution of empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy triggered by PD fluid cytology [1]. However, even with the current recommended protocols for microbiology, 15–20% of the PD peritonitis are culture negative [2]. Concerns for atypical infections or non-infectious peritonitis are higher in culture negative peritonitis. Neutrophilic reaction can also occur with peri-peritoneal infection or inflammation as in pancreatitis and colitis [3, 4].

Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) infection (CDI) presents with GI symptoms and has significant adverse outcomes including mortality, for both hospitalized and ambulatory patient populations [5,6,7]. Chronically ill and immunocompromised individuals, including those with end stage renal disease (ESRD), are at higher risk for developing CDI [8, 9]. These statistics along with the similar presenting syndromes, pose two unique challenges in the routine clinical care of ESRD patients on PD: GI presentation with cloudy PD effluent can detract from the timely diagnosis of CDI and empirical management of PD peritonitis with routinely recommended antimicrobials including cephalosporins negatively impacts CDI. Together, these could lead to inappropriate early management, prolonged disease course, and adverse patient outcomes [10]. A strategy that allows greater vigilance for diagnosing CDI, and appropriate antimicrobial administration without potential for worsening CDI may improve patient care in this population [11]. We present a potentially novel strategy for the empiric management of PD peritonitis through discussion of two such cases who received care in our medical center within a 12-month period.

Case presentation

Case #1

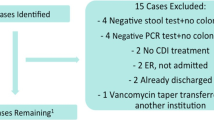

A 73-year-old male with Type II diabetes, ESRD managed with PD, and urethral stenosis managed by suprapubic catheter, presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with fever, abdominal pain, leukocytosis and significant diarrhea. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen demonstrated pan-colitis. Cell count of the peritoneal dialysis effluent revealed 1050 WBCs/mm3 with 71% neutrophils, 1% lymphocytes, and 28% monocytes. Clostridioides difficile PCR on the stool was positive. Patient was started on intra-peritoneal cefepime and vancomycin for treatment of the peritonitis and intravenous (IV) metronidazole and oral vancomycin for treatment of the C. difficile colitis. On day 3, due to development of ileus and worsening clinical status, oral vancomycin dose was increased to 500 mg every 6 h, vancomycin enemas were initiated along with IV tigecycline, and intra-peritoneal cefepime and vancomycin were discontinued. Peritoneal dialysate effluent culture produced no growth. IV metronidazole and vancomycin enemas were discontinued once the ileus resolved. Serial monitoring of the PD fluid with cell count was performed through day 11 and showed continued improvement in the WBC count. [Table 1] PD catheter was retained. Patient was discharged from the hospital on oral vancomycin taper after receiving 14 days of IV tigecycline.

Case #2

A 55-year-old male with ESRD secondary to polycystic kidney disease managed with PD developed acute diarrhea ranging from ten to twenty watery bowel movements per day. He became febrile on the second day of symptoms, and on the third day he noted a cloudy effluent from his dialysis catheter and presented to the ED. He denied pain at the site of the PD catheter, and no drainage was noted at the catheter exit site. Analysis of the peritoneal dialysate effluent found 1450 WBCs/mm3with 49% neutrophils, 49% monocytes, and 2% lymphocytes. Intra-peritoneal cefepime and vancomycin were initiated. CT of the abdomen identified “inflammatory changes of the rectosigmoid colon compatible with an infectious or inflammatory process.” C. difficile PCR of the stool was positive. Intra-peritoneal cefepime and vancomycin were promptly discontinued. Treatment with oral vancomycin 125 mg every 6 h and IV Tigecycline was initiated. Serial monitoring of the PD fluid with cell count was continued. By day 3, the WBC count in effluent fluid decreased to 25 cells/mm3. [Table 1] PD fluid culture produced no growth. PD catheter was retained. Tigecycline was discontinued after 5 days, and the patient was discharged on oral vancomycin to complete a 14-day course. At his 2-month follow-up clinic appointment, he had fully recovered.

Discussion and conclusions

CDI is a growing concern worldwide in both hospitalized and ambulatory patient populations. In the United States, one retrospective analysis found the incidence of CDI among hospitalized adults nearly doubled between 2001 and 2010 [12]. Further, there is worry that community-acquired CDI may be overlooked by the predominance of hospital-based studies. A population-based study in Minnesota found that community-acquired CDI accounted for 41% of all reported cases, which led the group to conclude the reported burden of disease is likely underestimated [13]. Additionally, CDI has a proclivity towards affecting those with chronic illness and immune-compromised state. As such ESRD patients with PD form a high-risk group for CDI [14].

CDI presents several unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in ESRD patients on PD. Although diarrhea remains the commonest symptom for CDI, overall clinical presentation of CDI can often be indistinguishable from PD peritonitis as many of these patients also present with sepsis, abdominal pain, tenderness, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Laroche et al. described the first case of C. difficile peritonitis in a patient undergoing chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) with a fatal outcome. PD fluid culture inoculated in blood culture bottles yielded Candida albicans and C. difficile. Interestingly, 3 weeks prior, the patient had received treatment for Bacteroides fragilis and Streptococcus spp peritonitis. Autopsy revealed no perforation or pseudomembranous colitis [15]. In another instance, Bharti et al. reported successful resolution of polymicrobial peritonitis in a 72-year-old man on CAPD. In this case, the PD fluid cultures using blood culture bottles revealed E. coli, B. fragilis, C. albicans and C. difficile. The identification of organisms was performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and treatment included antibiotics and PD catheter removal. As these cases demonstrate, isolation of C. difficile in PD peritonitis is uncommon and these are typically found in polymicrobial infections [16]. In contrast, Arikan et al. reported a 63-year-old male on PD who had previously been treated for pneumonia with piperacillin-tazobactam [17]. He presented with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and cloudy dialysate and was found to have CDI, with positive stool toxin B assay, and peritonitis, with effluent white blood cell count 1160/mm3 with neutrophil predominance and negative fluid culture. Similarly, Ribes-Cruz et al., reported a patient with watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and cloudy peritoneal effluent that failed to respond to IP ceftazidime and vancomycin [18]. Stool was positive for C. difficile toxin. Peritoneal dialysate was negative for C. difficile toxin or antigen however, clinical improvement was noted only after the initiation of oral vancomycin. Some studies have hypothesized the concerns for transmigration of bacteria as well as bacteremia and secondary peritoneal seeding as the pathophysiology of infectious peritonitis, whereas others have suggested the upregulation of ICAM-1 receptors causing chemoattraction and transmigration of leukocytes through the intestinal epithelium causing non-infectious peritonitis [19, 20]. Fulminant CDI with perforation and peritonitis has also been demonstrated [21, 22].

Taken together, these reports highlight a clinical conundrum when a PD patient presents with cloudy effluent, abdominal pain, and diarrhea likely secondary to CDI (Fig. 1). On one hand these patients may have a non-infectious neutrophilic reaction due to the presence of peri-peritoneal inflammation/colitis while on the other, the possibilities exist for a true bacterial peritonitis either with C. difficile itself or related to the other more conventional bacteria [4, 17, 18, 23]. Findings of cloudy effluent in these situations do not assist in establishing the diagnosis of either, and the current guidelines trigger empiric initiation of broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including third generation cephalosporins for the management of PD peritonitis. Unfortunately, these may worsen CDI. A strategy that allows for appropriate antimicrobial administration without potential for worsening CDI may improve patient care in this population [11].

Tigecycline, an intravenously administered glycylcycline, may provide an effective alternative to cephalosporins in this clinical scenario. It has antimicrobial activity covering gram-positive organisms including MRSA and VRE, gram-negative organisms as well as anaerobic bacteria and is an approved treatment of complex intra-abdominal infections including peritonitis [24, 25]. While not standard therapy for CDI, tigecycline has also been shown to have efficacy against C. difficile and has been reported as an effective adjunct for CDI in recent reports [26]. Herpers et al., in a case series demonstrated successful eradication of C. difficile in four severe refractory cases after the addition of IV tigecycline [27]. Duration of tigecycline therapy ranged between 7 to 24 days. Another retrospective cohort evaluating severe complicated, non-operative CDI showed similar outcomes in patients who received tigecycline compared to those who did not. Although, the study had a small sample size and was not powered to adjust for comorbidities and severity of illness [28]. Common side effects include nausea and vomiting while rare adverse effects of tigecycline are pancreatitis [29], hepatic dysfunction, hypersensitivity reactions with potential for low cross-reactivity to tetracyclines, photosensitivity, and pseudotumor cerebri. A black box warning exists for its use. A meta-analysis of Phase 3 and 4 clinical trials demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in tigecycline versus comparator treated patients, but the cause for this has not been determined, and use has been recommended to be reserved for specific indications [30].

In our report, Case 1 had an admission for pneumonia requiring antibiotics 1 month prior to presentation and Case 2 had a history of CDI. We used IV tigecycline as empiric treatment of possible PD associated infectious peritonitis while also providing adjunctive CDI treatment. We do not believe that tigecycline alone led to a positive treatment response but, our use of tigecycline was primarily to prevent worsening of C. difficile colitis. This enabled the treating physicians to avoid systemic administration of third generation cephalosporins while culture results on the dialysate fluid were awaited. The difference in duration of tigecycline between the two cases (14 days v/s 5 days) was because Case 1 had severe C. difficile disease and the peritoneal fluid cell count responded at a much slower rate as displayed in Table 1. Both our cases were eventually PD culture negative and thus were successfully managed with IV tigecycline and oral vancomycin without evidence for slowly responsive or refractory peritonitis. While we do not recommend combination therapy in every such patient, we feel that the empiric use of tigecycline could be considered in patients presenting with the diagnosis of CDI, or at high risk for CDI until the cause for their cloudy dialysate can be determined. This may allow appropriate coverage for the possible infectious agents without adversely impacting the CDI in those with neutrophilic reaction. In the latter cases, once PD fluid analysis shows improvement, tigecycline may be discontinued (Fig. 1).

In conclusion, the diagnosis of CDI is challenging and could be delayed or missed in PD patients presenting with diarrhea and cloudy peritoneal effluent with positive fluid cytology suggestive of PD peritonitis. CDI associated peritonitis may be inflammatory and not necessarily infectious. In patients presenting with diarrhea with risk factors for CDI, traditional empiric treatment of PD peritonitis may need to be reexamined as it could have detrimental effects on CDI course and patient outcomes. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate the ideal treatment strategy.

Availability of data and materials

All available data has been shared in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CDI:

-

Clostridioides difficile infection

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- ESRD:

-

End stage renal disease

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- PD:

-

Peritoneal dialysis

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

References

Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, de Arteaga J, Fan S, Figueiredo AE, Fish DN, Goffin E, Kim YL, Salzer W, et al. ISPD peritonitis recommendations: 2016 update on prevention and treatment. Perit Dial Int : J Int Soc Perit Dial. 2016;36(5):481–508.

Port FK, Held PJ, Nolph KD, Turenne MN, Wolfe RA. Risk of peritonitis and technique failure by CAPD connection technique: a national study. Kidney Int. 1992;42(4):967–74.

Teitelbaum I. Cloudy peritoneal dialysate: it's not always infection. Contrib Nephrol. 2006;150:187–94.

Rocklin MA, Teitelbaum I. Noninfectious causes of cloudy peritoneal dialysate. Semin Dial. 2001;14(1):37–40.

Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, McDonald LC, Pepin J, Wilcox MH. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431–55.

Frequently asked questions about Clostridium difficile for healthcare providers [https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cdiff/cdiff_clinicians.html]. Accessed 06/16/2019.

Gupta A, Khanna S. Community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: an increasing public health threat. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:63–72.

Phatharacharukul P, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Edmonds PJ, Mahaparn P, Bruminhent J. The risks of incident and recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):2913–22.

Tirath A, Tadros S, Coffin SL, Kintziger KW, Waller JL, Baer SL, Colombo RE, Huber LY, Kheda MF, Nahman NS Jr. Clostridium difficile infection in dialysis patients. J Invest Med : Official Publ Am Fed Clini Res. 2017;65(2):353–7.

Barbut F, Surgers L, Eckert C, Visseaux B, Cuingnet M, Mesquita C, Pradier N, Thiriez A, Ait-Ammar N, Aifaoui A, et al. Does a rapid diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection impact on quality of patient management? Clin Microbiol Infect : Official Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;20(2):136–44.

Bharti S, Malhotra P, Juretschko S. Successful treatment of peritoneal Dialysis catheter-related Polymicrobial peritonitis involving <span class="named-content genus-species" id="named-content-1">Clostridium difficile</span>. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(12):3945–6.

Reveles KR, Lee GC, Boyd NK, Frei CR. The rise in Clostridium difficile infection incidence among hospitalized adults in the United States: 2001-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(10):1028–32.

Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson SL, Kammer PP, Orenstein R, St Sauver JL, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. The epidemiology of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(1):89–95.

Eddi R, Malik MN, Shakov R, Baddoura WJ, Chandran C, Debari VA. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for Clostridium difficile infection. Nephrology (Carlton, Vic). 2010;15(4):471–5.

Laroche MC, Alfa MJ, Harding GKM. Isolation of toxigenic Clostridium difficile from dialysate fluid in a fatal case of chronic ambulatory peritoneal Dialysis-related peritonitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(5):1248.

Brook I, Walker RI. Pathogenicity of Clostridium species with other bacteria in mixed infections. J Infect. 1986;13(3):245–53.

Arikan T, Unal A, Kocyigit I, Yurci A, Oymak O. Peritoneal Dialysis-related peritonitis triggered by Clostridium difficile-associated colitis. Perit Dial Int : J Int Soc Perit Dial. 2014;34(1):139–40.

Ribes-Cruz JJ, Gonzalez-Rico M, Juan-Garcia I, Puchades-Montesa MJ, Torregrosa-Maicas I, Ramos-Tomas C, Solis-Salguero MA, Tomas-Simo P, Tejedor-Alonso S, Zambrano-Esteves P, et al. Cloudy peritoneal effluent and diarrhoea due to Clostridium difficile. Nefrol : Publ oficial de la Soc Esp Nefrol. 2014;34(1):130–1.

Canny G, Drudy D, Macmathuna P, O'Farrelly C, Baird AW. Toxigenic C. difficile induced inflammatory marker expression by human intestinal epithelial cells is asymmetrical. Life Sci. 2006;78(9):920–5.

Liberek T, Chmielewski M, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Lewandowski K, Rutkowski B. Transmigration of blood leukocytes into the peritoneal cavity is related to the upregulation of ICAM-1 (CD54) and mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) adhesion molecules. Perit Dial Int : J Int Soc Perit Dial. 2004;24(2):139–46.

Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ, van Dissel JT. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID): treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Clin Microbiol Infect : Official Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;15(12):1067–79.

Sartelli M, Di Bella S, McFarland LV, Khanna S, Furuya-Kanamori L, Abuzeid N, Abu-Zidan FM, Ansaloni L, Augustin G, Bala M, et al. 2019 update of the WSES guidelines for management of Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection in surgical patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14(1):8.

Sakao Y, Kato A, Sugiura T, Fujikura T, Misaki T, Tsuji T, Sakakima M, Yasuda H, Fujigaki Y, Hishida A. Cloudy dialysate and pseudomembranous colitis in a patient on CAPD. Perit Dial Int : J Int Soc Perit Dial. 2008;28(5):562–3.

Eckmann C, Montravers P, Bassetti M, Bodmann KF, Heizmann WR, Sanchez Garcia M, Guirao X, Capparella MR, Simoneau D, Dupont H. Efficacy of tigecycline for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections in real-life clinical practice from five European observational studies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(Suppl 2):ii25–35.

Oliva ME, Rekha A, Yellin A, Pasternak J, Campos M, Rose GM, Babinchak T, Ellis-Grosse EJ, Loh E. A multicenter trial of the efficacy and safety of tigecycline versus imipenem/cilastatin in patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections [Study ID Numbers: 3074A1–301-WW; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00081744]. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:88.

El-Herte RI, Baban TA, Kanj SS. Recurrent refractory Clostridium difficile colitis treated successfully with rifaximin and tigecycline: a case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44(3):228–30.

Herpers BL, Vlaminckx B, Burkhardt O, Blom H, Biemond-Moeniralam HS, Hornef M, Welte T, Kuijper EJ. Intravenous tigecycline as adjunctive or alternative therapy for severe refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis : Official Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2009;48(12):1732–5.

MT LS, Branch-Elliman W, Snyder GM, Mahoney MV, Alonso CD, Gold HS, Wright SB. Does Adjunctive Tigecycline Improve Outcomes in Severe-Complicated, Nonoperative Clostridium difficile Infection? Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(1):ofw264.

Lin J, Wang R, Chen J. Tigecycline-induced acute pancreatitis in a renal transplant patient: a case report and literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):201.

Tygacil (tigecycline) iv injection label – FDA [https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021821s026s031lbl.pdf]. Accessed 16 June 2019.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

AMS reports the following ongoing grant supports: I01HX002639 HSR&D, Department of Veterans Affairs and I01CX001661, CSR&D, Department of Veteran Affairs. The funding agency did not have any role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of data or in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS wrote the initial manuscript, edited and reviewed the manuscript, KC, KBP, KLW and AMS contributed, edited and performed literature review. All authors contributed significantly, have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was required for this case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review.

Competing interests

All authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, K.J., Cherabuddi, K., Pressly, K.B. et al. Clostridioides difficile associated peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients – a case series based review of an under-recognized entity with therapeutic challenges. BMC Nephrol 21, 76 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01734-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01734-8