Abstract

Background

Delta neutrophil index (DNI), representing an elevated fraction of circulating immature granulocytes in acute infection, has been reported as a useful marker for predicting mortality in patients with sepsis. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognostic value of DNI in predicting mortality in septic acute kidney injury (S-AKI) patients treated with continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT).

Method

This is a retrospective analysis of consecutively CRRT treated patients. We enrolled 286 S-AKI patients who underwent CRRT and divided them into three groups based on the tertiles of DNI at CRRT initiation (high, DNI > 12.0%; intermediate, 3.6–12.0%; low, < 3.6%). Patient survival was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards models to determine the effect of DNI on the mortality of S-AKI patients.

Results

Patients in the highest tertile of DNI showed higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score (highest tertile, 27.9 ± 7.0; lowest tertile, 24.6 ± 8.3; P = 0.003) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (highest tertile, 14.1 ± 3.0; lowest tertile, 12.1 ± 4.0; P = 0.001). The 28-day mortality rate was significantly higher in the highest tertile group than in the lower two tertile groups (P < 0.001). In the multiple Cox proportional hazard model, DNI was an independent predictor for mortality after adjusting multiple confounding factors (hazard ratio, 1.010; 95% confidence interval, 1.001–1.019; P = 0.036).

Conclusion

This study suggests that DNI is independently associated with mortality of S-AKI patients on CRRT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common and serious complication in critically ill patients [1, 2]. Septic AKI (S-AKI) accounts for close to 50% of all cases of AKI in the intensive care unit (ICU), and affects between 15 and 20% of patients in the ICU [3]. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) is an established treatment modality in critically ill patients with AKI in the ICU [4]. CRRT has several advantages in regard with the hemodynamic stability in patients with sepsis compared to intermittent renal replacement therapy including traditional dialysis and ultrafiltration therapy [5, 6].

In spite of potential advantages of CRRT in the management of S-AKI, the mortality rate in this patient group remains extremely high [7, 8]. To identify the predictors of mortality rate in S-AKI patients on CRRT treatment, several observational studies have been described [9, 10]. Previous studies focused on not only variable clinical factors but also sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) related inflammatory mediators. Circulating pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-8, play an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of S-AKI and have been introduced as potential biomarkers of S-AKI. C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin were used to help predict mortality risk in patients with sepsis [11–13]. However, these biomarkers have not been found to be easily applicable due to limitations of timeliness and cost-effectiveness in critically ill S-AKI patients [12, 14].

Delta neutrophil index (DNI), calculated by subtracting the fraction of mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes from myeloperoxidase (MPO) reactive cells, represents proportion of circulating immature granulocytes (IGs). DNI is provided by an automatic hematologic analyzer ADVIA2120 (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Forchheim, Germany) using MPO and nuclear lobularity channels [15]. A previous study demonstrated that, compared with white blood cells (WBCs) or CRP levels, DNI is a more useful marker for predicting mortality in patients with sepsis [16]. DNI has several advantages: it is simple, automatically reported, and rapidly recognized. However, little is known about the prognostic role of DNI in S-AKI patients, especially those treated with CRRT. Therefore, in this study, we explored whether high DNI is associated with high mortality rates in S-AKI patients receiving CRRT treatment at a single ICU center in Republic of Korea.

Methods

Study subjects

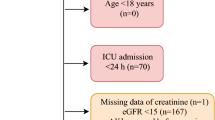

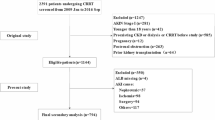

All data from patients were retrieved from CRRT Database at Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System (YUHS) in Seoul, Republic of Korea. YUHS operates a specialized CRRT team (SCT), which includes physicians and nurses who are especially trained and educated in performing CRRT. Related details have been previously described [8]. Through a retrospective review of the consecutively registered CRRT Database, 628 patients who started CRRT from August 2011 to September 2013 were considered eligible for the present study. We excluded 121 patients who were younger than 18 years and/or the presence of a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order. Because DNI values do not adequately work in immunocompromised individuals [17], the subject seems like has the components of immune suppression such as individuals those who have previously experienced chronic dialysis, or diagnosed with advanced stage IV malignancies, liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh C), or higher than 40 points with Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score at enrollment were also excluded. The survival analysis according to the DNI groups was only performed with S-AKI populations (n = 286, Fig. 1).

To define the sepsis, we followed the consensus conference criteria from the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine [18]. The individual those who had clinical findings supposed infection and simultaneously had 2 consecutive factors agree with SIRS, they diagnosed as the presence of sepsis. In SIRS, at least 2 of the following criteria were required: 1) core temperature > 38 °C or < 36 °C, 2) heart rate > 90 beats per minute, 3) respiratory rate > 20 breaths per minute, 4) arterial partial pressure of CO2 < 32 mmHg, 5) peripheral leukocyte count > 12,000/mm3 or < 4,000/mm3 [19]. To define SIRS, we used the results of vital signs and biochemical tests that were measured just before beginning of CRRT.

We included AKI patients with injury or failure stage of Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease (RIFLE) criteria at the time of CRRT initiation [20]. S-AKI was defined as SIRS combined with an infectious episode and renal dysfunction.

Data collection

Depending on the protocol performed by SCT, all patients receiving CRRT were recorded with demographic and biochemical data including DNI at the beginning of CRRT, and these information were collected retrospectively for present analyses. Actually, blood samples comprising resource for DNI calculation was retrieved at the time immediately before the initiation of CRRT. Data of complete blood cell (CBC) counts were collected from an automated hematology analyzer (ADVIA 2120). DNI was calculated using the following formula: DNI (%) = (the leukocyte subfraction assayed in the MPO channel by cytochemical reaction) − (leukocyte subfraction counted in the nuclear lobularity channel by reflected light beam) [15]. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was defined as diastolic pressure plus a third of the pulse pressure, and recorded at the time of initiating CRRT. For the assessment of disease severity, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, APACHE II score, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were evaluated at the start of CRRT treatment. Comorbidities were defined by diagnosis codes based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision. Subjects who were taking antihypertensive or antidiabetic medications were also considered hypertensive or having diabetes, respectively. The following biochemical laboratory test result data were collected: hemoglobin, WBCs, platelet, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, serum albumin, high sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP), total bilirubin, prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by using the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equation [21], and hs-CRP levels were determined by a latex-enhanced immunonephelometric method using a BNII analyzer (Dade Behring, Newark, DE, USA).

ICU setting and CRRT protocol

The investigation site was a self-contained, 99-bed medical and surgical ICU in a 2076-bed teaching hospital in Seoul, Republic of Korea, equipped with 15 CRRT machines. CRRT initiation criteria include medically intractable and persistent electrolyte imbalance and/or metabolic acidosis, as well as decreased urine volume with overhydrated status and/or progressive azotemia. Hemodynamic instability was also considered an important factor in decision-making. However, the final decision to start CRRT was based on comprehensive judgment of various indications. Specifically, decisions to determine CRRT settings, which included target removal, blood flow, dialysate and replacement fluid rates, and the use of anticoagulant, were finalized by the nephrologist after close consultations and discussions between nephrologists, physicians, and ICU practitioners. Vascular accesses for CRRT have been selected among via the femoral, internal, or subclavian veins according to their availability and combined comorbidities. In most patients, continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) was performed using the PRISMA platform (Gambro, Hechingen, Germany). CRRT was initiated with a blood flow rate of 100 mL/min, which was gradually increased to 150 mL/min. The ultrafiltration dose was targeted to 40 mL/kg/h, and Hemosol (Gambro) was replaced using a predilution method. In addition, CRRT circuits were exchanged regularly every 48 h or when the blood pump was stopped. The patients were weighted every morning using an in-bed scale, and the ultratfiltration dose was adjusted [22].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software for Windows version 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were presented as means as standard deviation, and categorical variables as numbers and percentages. Patients were divided into three groups based on tertiles of DNI values at CRRT initiation: high, intermediate, and low DNI groups. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to analyze the normality of the distribution of parameters. Baseline characteristics according the trichotomized DNI groups were compared using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Nonparametric variables were expressed as median and interquartile range and compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. To compare differences of continuous parameters between survivors and non-survivors, Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test were used for parametric or non-parametric variables, respectively. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess the relationship between DNI and variable selected clinical parameters. In the present study, we evaluated 28-day all-cause mortality as an end point. Survival curves were generated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and between-group survival was compared by the log-rank test. We conducted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to compare the predictive accuracy of DNI and SOFA scores, and area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. In addition, we graded by DNI on a scale of 1–3 (DNI < 3.6%, 1; 3.6% ≤ DNI ≤ 12.0%, 2; DNI > 12.0%, 3) and added to the baseline SOFA score. The independent prognostic values of clinical parameters for the study outcome were analyzed by multiple Cox regression analysis. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with the use of the estimated regression coefficients and standard errors in the Cox regression analysis. The independent association of DNI levels for the 28-day all-cause mortality was confirmed by multiple logistic regression analysis. All probabilities were two-tailed and the level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Population characteristics

The demographic and biochemical characteristics of the study population with S-AKI are shown in Table 1. At the time of ICU admission, 129 (45.1%), 82 (28.7%), and 75 (26.2%) patients were classified as RIFLE-R, −I, and -F, respectively. Meanwhile, 177 (61.9%) patients were classified as RIFLE-I, and the remaining 109 (38.1%) patients were classified as RIFLE-F at the time of CRRT. DNI values ranged from 0 to 73.40%, with a median of 6.10%. When the patients were divided into three groups based on the tertiles of DNI level at CRRT initiation (high, DNI > 12.0%; intermediate, 3.6–12.0%; low, < 3.6%), patients with the highest tertile of DNI had higher APACHE II scores (27.9 ± 7.0 vs. 24.6 ± 8.3, P = 0.003) and SOFA scores (14.1 ± 3.0 vs. 12.1 ± 4.0, P = 0.001) compared to the lowest tertile group. Patients with the highest tertile of DNI had lower MAP, WBCs, platelet, and total cholesterol levels. In addition, they had more prolonged PT and aPTT. However, there were no significant differences in age, gender, CCI score, hemoglobin, eGFR, and hs-CRP among three groups.

When the study population divided into two groups according to their mortality events, non-survivor group showed significantly higher APACHE II (28.1 ± 7.3 vs. 24.0 ± 7.5, P < 0.001) and SOFA (14.2 ± 3.1 vs. 10.8 ± 3.7, P < 0.001) score, higher DNI [8.35 (3.23–24.73) vs. 3.95 (2.35–9.10) %, P < 0.001], PT (1.7 ± 0.8 vs. 1.5 ± 0.6 INR, P = 0.007), and aPTT (53.1 ± 31.9 vs. 40.4 ± 14.6 s, P < 0.001) levels compared with survivor group, while MAP (73.1 ± 12.8 vs. 81.7 ± 13.9 mmHg, P < 0.001), history of hypertension [65 (33.9%) vs. 46 (48.9%), P = 0.014] and diabetes [58 (30.2%) vs. 40 (42.6%), P = 0.039], WBCs [10.6 (4.0–17.5) vs. 13.9 (8.9–20.3) 103/mm3, P = 0.009], platelet counts [80 (44–129) vs. 114 (57–204) 103/mm3, P = 0.002], and serum albumin concentrations (2.6 ± 0.6 vs. 2.8 ± 0.7 g/dL, P = 0.013) were significantly lower in non-survivor group (Table 2).

Associations between DNI values and other parameters

There were significant negative correlations between baseline DNI values and MAP (r = −0.159, P = 0.007), platelets (r = −0.219, P < 0.001), and albumin (r = −0.150, P = 0.012). In contrast, there were positive correlations between baseline DNI values and APACHE II score (r = 0.119, P = 0.045), SOFA score (r = 0.166, P = 0.005), PT (r = 0.160, P = 0.008), and aPTT (r = 0.268, P < 0.001). There was no correlation in DNI levels with WBC, eGFR, and hs-CRP (Table 3).

Risk analysis for all-cause mortality

During the study period, 192 (67.1%) patients died. Twenty-eight-day mortality rate was significantly higher in the highest DNI group compared with intermediate and lowest DNI groups (80.2 vs. 64.6 vs. 56.4%, P < 0.001, Fig. 2). In Cox regression analysis in which DNI levels were treated as a continuous variable, DNI level was significantly associated with 28-day mortality (per 1% increase of DNI; HR 1.014; 95% CI, 1.007–1.022; P < 0.001) (Table 4, Model 1). After adjustment for age, gender, MAP, and SOFA score were included in a multivariate model, DNI remained an independent predictor of 28-day mortality (HR 1.011; 95% CI, 1.003–1.019; P = 0.010) (Table 4, Model 3). In addition, the significance was remained even more adjustment for platelet, albumin, PT, and aPTT (HR 1.010; 95% CI, 1.001–1.019; P = 0.036) (Table 4, Model 4). Meanwhile, we did not find any significant differences according to DNI levels in patients with non-S-AKI (data not shown, Model 4, P = 0.638).

The relationship between the 28-day mortality rates and DNI values was confirmed by multiple logistic regression analyses with adjustments for multiple confounding factors (Table 4). In the fully adjusted model, increased DNI levels were still independently associated with the risk of 28-day mortality event in S-AKI patients [DNI, 1% increase, odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.024 (1.002–1.046), P = 0.031]. The ROC curves using variables (DNI value, hs-CRP, and WBC counts) are plotted in Fig. 3. The AUCs of DNI value and hs-CRP for 28-day all-cause mortality were 0.635 and 0.526, respectively (P < 0.001, Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that DNI value is closely related to severity of disease in patients with S-AKI. In addition, baseline DNI level is independently associated with mortality in S-AKI patients treated with CRRT, even after adjusting for other established prognostic variables such as SOFA score.

DNI is the difference between the leukocyte differential assayed in the MPO channel and that measured in the nuclear lobularity channel, and was initially designed as a reliable and reproducible method to reflect IGs in circulating blood. The shift to the left of neutrophils, which reflects elevated IGs, has been characterized in sepsis and SIRS. Leukocyte count could be variable according to severity of sepsis in patients in the ICU. WBC count can increase in response to bacterial infection. Meanwhile, sepsis-associated leukopenia has been explained by impaired bone marrow production and peripheral overconsumption and/or destruction in response to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Several studies reported that DNI was closely related to sepsis severity [23], detection rate of blood cultures [24], DIC scores [15], and mortality in patients with suspected sepsis [16]. Moreover, another study showed that DNI may serve as a more useful diagnostic and prognostic marker than lactate for early diagnosis of disease severity in patients with septic shock [25]. More recently, leaving the usefulness of DNI on the field of critical medicine aside, DNI showed the association with several inflammatory status which could be overlooked by clinicians such as acute appendicitis, low-grade community-acquired pneumonia, or pyelonephritis in transplanted subjects [26–28]. There were no significant differences in WBC counts or neutrophil proportion among the groups categorized using DNI values. In addition, WBC counts alone did not predict patient outcomes. However, there were significant relationships between DNI and DIC-related parameters, including platelet count, PT, and aPTT. These findings added to the evidence that baseline DNI is a significant determinant of mortality in AKI patients requiring CRRT. In addition, DNI is routinely performed and automatically calculated without additional costs. DNI values can be rapidly recognized in the CBC report. Taken together, we surmised that DNI could be an early and potent prognostic indicator in patients with S-AKI.

Although DNI as a prognostic marker for sepsis might be comparable to other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as CRP and procalcitonin, DNI can change in conditions of ineffective leukocyte production. Since the production of IGs and DNI values could be suppressed in immunocompromised patients, DNI value alone could not discriminate between bacteremia and non-bacteremia in these patients. In addition, the production of IGs may be altered in neonates, pregnant women, and patients with other hematologic diseases or bone marrow alterations. Under these conditions, DNI should be interpreted with caution, and other biomarkers, such as CRP and procalcitonin, might be included to assess the severity of SIRS or sepsis.

Even though the present study measured IGs using the ADVIA automatic analyzer, several other hematology analyzers can obtain IG counts. The Cell-Dyn series analyzer counts the IG fraction using a 4-dimensional optical scanner and multi-parameter flow cytometry, and the Sysmex analyzer also enumerates IG counts using the difference of fluorescence between mature and immature granulocytes, similar to the ADVIA analyzer. Further comparative analyses among these techniques might be conducted to validate the clinical usefulness in sepsis patients including S-AKI patients.

Predictive scoring systems have been developed to measure the severity of disease and the prognosis of patients with sepsis in the ICU [29, 30]. However, these scoring systems have important limitations, such as inaccuracy according to the type of disease [31–33], lead time bias [34], and need for updating [35]. The accuracy of prediction of mortality with severity scoring indices alone is relatively poor. Therefore, other factors such as serologic makers related to sepsis must be considered together to predict the outcome in severe sepsis. A recent study demonstrated that pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1ß, and IL-6 are important clinical prognostic markers in patients with systemic sepsis. There is a strong correlation between serum concentration of pro-inflammatory mediators and mortality in septic patients [36]. In spite of this advantage, most of these mediators are not established for clinical decision-making due to their short half-life. In addition, the same goal could be achieved more easily and cheaply by the estimation of blood lactate level.

AKI has long been considered primarily as a hemodynamic condition characterized by a reduction of renal blood flow, induced by either cardiogenic or septic shock [37]. However, Bellomo et al. produced new and interesting data in animal models of S-AKI that undermined existing concepts. They observed that medullary and cortical renal blood flow were both maintained and even increased in septic shock, underscoring that S-AKI was a totally different physiological phenomenon than non-S-AKI [38]. Inflammation is now believed to play a major role in the pathophysiology of S-AKI [39]. In fact, it is known that TNF-α can induce AKI [40], and Benes et al. found an early increase in TNF-α in animals developing S-AKI [41]. In addition, recent work highlighted the fact that inflammatory apoptosis could play a more important role in sepsis and septic shock than pure necrosis [42]. Interestingly, Simmons et al. suggested that an increase in plasma pro-inflammatory cytokine levels could predict mortality in patients with AKI. However, unlike other sepsis studies which showed that pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1ß and TNF-α could predict mortality, this study did not confirm such a relationship. Instead, IL-6 and IL-8, which were often considered secondary in the inflammatory cascades involving IL-1ß or TNF-α, were proven to be significant predictors of mortality. The authors suggested that renal failure may in and of itself confer an altered cytokine profile even in the context of critical illness. Another potential explanation for this discrepancy may be the timing of cytokine determination in the overall course of illness [43]. Therefore, the extent to which inflammatory mediators affect the prognosis in patients with S-AKI remains uncertain.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not evaluate follow-up data for DNI levels and thus could not account for possible variation over time. Since DNI levels can change according to the response to optimal treatment such as antibiotics, repeated measurement of DNI can serve as a helpful predictor of prognosis in patients with sepsis or SIRS. Further study to clarify the relationship of changes in DNI levels over time with prognosis might be valuable. Second, there was no investigation of pro-inflammatory cytokines related to sepsis in patients with S-AKI. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1ß, and IL-6 play a more important role in the pathogenesis of sepsis and septic shock. In addition, there is a strong correlation between serum concentration of pro-inflammatory mediators and mortality in septic patients. The investigation of pro-inflammatory cytokines compared with DNI might be helpful in predicting outcomes in patients with S-AKI in the future. Third, DNI values have limitations for assessing bacteremia in immunocompromised individuals, thus there might be inadequate estimation in patients with severe immune suppression [17]. To mitigate these bias we initially excluded subjects those who considered immunocompromised. Lastly, in a group with high risk of death, clinical significance of the statistically significant relationship between DNI and mortality is limited. In this study, AUC of DNI was higher than that of WBC or CRP; however, its absolute value was still low. Future development of prediction models, including DNI through various approaches, will be helpful for such high-risk patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study revealed that a greater increase in DNI levels is significantly associated with severity of disease and high mortality rates in S-AKI patients treated with CRRT. DNI is an early identifiable and reliable serologic maker to predict outcomes in patients with S-AKI requiring CRRT. Patients with high DNI levels should be cautiously monitored and treatment strategies should be appropriately adapted for their future needs.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- aPTT:

-

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CBC:

-

Complete blood cell

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- CRRT:

-

Continuous renal replacement therapy

- CVVHDF:

-

Continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration

- DIC:

-

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- DNI:

-

Delta neutrophil index

- DNR:

-

Do-not-resuscitate

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- hs-CRP:

-

High sensitivity C-reactive protein

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IGs:

-

Immature granulocytes

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- MPO:

-

Myeloperoxidase

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- RIFLE:

-

Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- S-AKI:

-

Septic acute kidney injury

- SCT:

-

Specialized continuous renal replacement therapy team

- SIRS:

-

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- WBCs:

-

White blood cells

References

Mehta RL, Pascual MT, Soroko S, Savage BR, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, Paganini EP, Chertow GM. Spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit: the PICARD experience. Kidney Int. 2004;66(4):1613–21.

Choi HM, Kim SC, Kim MG, Jo SK, Cho WY, Kim HK. Etiology and outcomes of anuria in acute kidney injury: a single center study. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2015;34(1):13–9.

Wan L, Bagshaw SM, Langenberg C, Saotome T, May C, Bellomo R. Pathophysiology of septic acute kidney injury: what do we really know? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4 Suppl):S198–203.

Lins RL, Elseviers MM, Van der Niepen P, Hoste E, Malbrain ML, Damas P, Devriendt J. Intermittent versus continuous renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury patients admitted to the intensive care unit: results of a randomized clinical trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(2):512–8.

Forni LG, Hilton PJ. Continuous hemofiltration in the treatment of acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(18):1303–9.

Joannidis M. Continuous renal replacement therapy in sepsis and multisystem organ failure. Semin Dial. 2009;22(2):160–4.

Oh HJ, Park JT, Kim JK, Yoo DE, Kim SJ, Han SH, Kang SW, Choi KH, Yoo TH. Red blood cell distribution width is an independent predictor of mortality in acute kidney injury patients treated with continuous renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(2):589–94.

Oh HJ, Lee MJ, Kim CH, Kim DY, Lee HS, Park JT, Na S, Han SH, Kang SW, Koh SO, et al. The benefit of specialized team approaches in patients with acute kidney injury undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy: propensity score matched analysis. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):454.

Sasaki S, Gando S, Kobayashi S, Nanzaki S, Ushitani T, Morimoto Y, Demmotsu O. Predictors of mortality in patients treated with continuous hemodiafiltration for acute renal failure in an intensive care setting. ASAIO J. 2001;47(1):86–91.

Wald R, Deshpande R, Bell CM, Bargman JM. Survival to discharge among patients treated with continuous renal replacement therapy. Hemodial Int. 2006;10(1):82–7.

Harbarth S, Holeckova K, Froidevaux C, Pittet D, Ricou B, Grau GE, Vadas L, Pugin J. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(3):396–402.

Herzum I, Renz H. Inflammatory markers in SIRS, sepsis and septic shock. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(6):581–7.

Phua J, Koay ES, Lee KH. Lactate, procalcitonin, and amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide versus cytokine measurements and clinical severity scores for prognostication in septic shock. Shock. 2008;29(3):328–33.

Kibe S, Adams K, Barlow G. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of sepsis in critical care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66 Suppl 2:ii33–40.

Nahm CH, Choi JW, Lee J. Delta neutrophil index in automated immature granulocyte counts for assessing disease severity of patients with sepsis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;38(3):241–6.

Seok Y, Choi JR, Kim J, Kim YK, Lee J, Song J, Kim SJ, Lee KA. Delta neutrophil index: a promising diagnostic and prognostic marker for sepsis. Shock. 2012;37(3):242–6.

Ahn JG, Choi SY, Kim DS, Kim KH. Limitation of the delta neutrophil index for assessing bacteraemia in immunocompromised children. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;436:319–22.

Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–55.

Zahar JR, Timsit JF, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Francais A, Vesin A, Descorps-Declere A, Dubois Y, Souweine B, Haouache H, Goldgran-Toledano D, et al. Outcomes in severe sepsis and patients with septic shock: pathogen species and infection sites are not associated with mortality. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(8):1886–95.

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8(4):R204–12.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro 3rd AF, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12.

Oh HJ, Shin DH, Lee MJ, Koo HM, Doh FM, Kim HR, Han JH, Park JT, Han SH, Yoo TH, et al. Early initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy improves patient survival in severe progressive septic acute kidney injury. J Crit Care. 2012;27(6):743.e749–718.

Park BH, Kang YA, Park MS, Jung WJ, Lee SH, Lee SK, Kim SY, Kim SK, Chang J, Jung JY, et al. Delta neutrophil index as an early marker of disease severity in critically ill patients with sepsis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:299.

Lee CH, Kim J, Park Y, Park YC, Kim Y, Yoon KJ, Uh Y, Lee KA. Delta neutrophil index discriminates true bacteremia from blood culture contamination. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;427:11–4.

Zanaty OM, Megahed M, Demerdash H, Swelem R. Delta neutrophil index versus lactate clearance: Early markers for outcome prediction in septic shock patients. Alexandria J Med. 2012;48(4):327–33.

Kim H, Kim Y, Kim KH, Yeo CD, Kim JW, Lee HK. Use of delta neutrophil index for differentiating low-grade community-acquired pneumonia from upper respiratory infection. Ann Lab Med. 2015;35(6):647–50.

Kim OH, Cha YS, Hwang SO, Jang JY, Choi EH, Kim HI, Cha K, Kim H, Lee KH. The use of delta neutrophil index and myeloperoxidase index for predicting acute complicated appendicitis in children. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148799.

Shin DH, Kim EJ, Kim SJ, Park JY, Oh J. Delta neutrophil index as a marker for differential diagnosis between acute graft pyelonephritis and acute graft rejection. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135819.

Ho KM, Dobb GJ, Knuiman M, Finn J, Lee KY, Webb SA. A comparison of admission and worst 24-h Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores in predicting hospital mortality: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2006;10(1):R4.

Vincent JL, de Mendonca A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, Sprung CL, Colardyn F, Blecher S. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1793–800.

Barie PS, Hydo LJ, Fischer E. Comparison of APACHE II and III scoring systems for mortality prediction in critical surgical illness. Arch Surg. 1995;130(1):77–82.

Brown MC, Crede WB. Predictive ability of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II scoring applied to human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. Crit Care Med. 1995;23(5):848–53.

Lewinsohn G, Herman A, Leonov Y, Klinowski E. Critically ill obstetrical patients: outcome and predictability. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(9):1412–4.

Escarce JJ, Kelley MA. Admission source to the medical intensive care unit predicts hospital death independent of APACHE II score. JAMA. 1990;264(18):2389–94.

Nassar Jr AP, Mocelin AO, Nunes AL, Giannini FP, Brauer L, Andrade FM, Dias CA. Caution when using prognostic models: a prospective comparison of 3 recent prognostic models. J Crit Care. 2012;27(4):423.e421–427.

Casey LC, Balk RA, Bone RC. Plasma cytokine and endotoxin levels correlate with survival in patients with the sepsis syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(8):771–8.

Schrier RW, Wang W. Acute renal failure and sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(2):159–69.

Bellomo R, Wan L, Langenberg C, May C. Septic acute kidney injury: new concepts. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2008;109(4):e95–100.

Akcay A, Nguyen Q, Edelstein CL. Mediators of inflammation in acute kidney injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:137072.

Tracey KJ, Beutler B, Lowry SF, Merryweather J, Wolpe S, Milsark IW, Hariri RJ, Fahey 3rd TJ, Zentella A, Albert JD, et al. Shock and tissue injury induced by recombinant human cachectin. Science. 1986;234(4775):470–4.

Benes J, Chvojka J, Sykora R, Radej J, Krouzecky A, Novak I, Matejovic M. Searching for mechanisms that matter in early septic acute kidney injury: an experimental study. Crit Care. 2011;15(5):R256.

Jacobs R, Honore PM, Joannes-Boyau O, Boer W, De Regt J, De Waele E, Collin V, Spapen HD. Septic acute kidney injury: the culprit is inflammatory apoptosis rather than ischemic necrosis. Blood Purif. 2011;32(4):262–5.

Simmons EM, Himmelfarb J, Sezer MT, Chertow GM, Mehta RL, Paganini EP, Soroko S, Freedman S, Becker K, Spratt D, et al. Plasma cytokine levels predict mortality in patients with acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2004;65(4):1357–65.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Brain Korea 21 PLUS Project for Medical Science, Yonsei University College of Medicine, and a grant of the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI10C2020).

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the study is presented in the manuscript or available upon request from the corresponding author of this manuscript, Tae-Hyun Yoo.

Authors’ contributions

IMH, CYY, DHS, and THY are responsible for the study concept and design, and was assisted by YKK, SGH, YEK, KSP, MJL, HJO, JTP, SHH, and SWK. IMH acquired the data. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data. IMH, DHS, and THY drafted the manuscript. CYY and THY critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. IMH, CYY, and THY were responsible for the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. THY supervised the study and is guarantors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System Clinical Trial Center. Written informed consent from all participants or their relatives was obtained before start of CRRT after explanation of CRRT-related possible complications.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, I.M., Yoon, CY., Shin, D.H. et al. Delta neutrophil index is an independent predictor of mortality in septic acute kidney injury patients treated with continuous renal replacement therapy. BMC Nephrol 18, 94 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-017-0507-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-017-0507-8