Abstract

Background

Haemodialysis (HD) patients suffer from an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Skin autofluorescence (SAF) is a strong marker for CVD. SAF indirectly measures tissue advanced glycation end products (AGE) being cumulative metabolites of oxidative stress and cytokine-driven inflammatory reactions. The dialysates often contain glucose.

Methods

Autofluorescence of skin and plasma (PAF) were measured in patients on HD during standard treatment (ST) with a glucose-containing dialysate (n = 24). After that the patients were switched to a glucose-free dialysate (GFD) for a 2-week period. New measurements were performed on PAF and SAF after 1 week (M1) and 2 weeks (M2) using GFD. Nonparametric paired statistical analyses were performed between each two periods.

Results

SAF after HD increased non-significantly by 1.2% while when a GFD was used during HD at M1, a decrease of SAF by 5.2% (p = 0.002) was found. One week later (M2) the reduction of 1.6% after the HD was not significant (p = 0.33). PAF was significantly reduced during all HD sessions. Free and protein-bound PAF decreased similarly whether glucose containing or GFD was used. The HD resulted in a reduction of the total PAF of approximately 15%, the free compound of 20% and the protein bound of 10%. The protein bound part of PAF corresponded to approximately 56% of the total reduction. The protein bound concentrations after each HD showed the lowest value after 2 weeks using glucose-free dialysate (p < 0.05). The change in SAF could not be related to a change in PAF.

Conclusions

When changing to a GFD, SAF was reduced by HD indicating that such measure may hamper the accumulation and progression of deposits of AGEs to protein in tissue, and thereby also the development of CVD. Glucose-free dialysate needs further attention. Protein binding seems firm but not irreversible.

Trial registration

ISRCTN registry: ISRCTN13837553. Registered 16/11/2016 (retrospectively registered).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are increased in patients with decreasing kidney function [1, 2] and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). HD patients have a five-fold shorter life expectancy than age-related healthy persons [3, 4]. One factor to consider is glucose that binds to amino residues forming glycated Schiff bases, with later rearrangements forming a more stable but still reversible Amadori product. Over time, these products undergo rearrangements including crosslinking to become irreversible advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Thereby both circulating and tissue proteins, as well as lipids and nucleic acids, may be glycated and crosslinked with collagen in the skin and other tissues [5, 6].

AGEs are considered as uremic toxins and contribute to cardiovascular complications of HD patients [7, 8]. AGEs accumulate more in HD because of increased production by oxidative stress caused by the dialysis per se [9] and lowered elimination by the impaired kidneys [10]. Skin autofluorescence (SAF) is related to the accumulation of AGE and is one of the strongest prognostic markers of mortality in these patients [8]. SAF is an indirect marker for glucose degradation products [8], present not only in the skin but also in other tissues [11].

Consumption of specific foods is associated with increased AGEs [12–14]. Another source of exposure to glucose in HD patients might be the use of glucose-containing dialysate. The use of glucose in dialysate has changed several times in the history of dialysis. In the early days of HD treatment, the use of dialysates containing a high glucose concentration was important to achieve an effective osmotic ultrafiltration [15]. Later, the use of ultrafiltration by hydrostatic pressure was developed and found superior [16]. The use of glucose in the dialysate decreased and many dialysis units switched to a glucose free concentrate [17]. However, the disadvantage of non-glucose-containing dialysate was the increased risk for hypoglycemia in patients with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus and lack of a valuable addition to energy in malnourished HD patients [14, 18–21].

In previous studies, we were able to show that a single session of HD significantly reduced plasma autofluorescence (PAF) but not SAF [22]. The use of either high-flux versus low-flux dialyzers did not change SAF after HD as well [23]. Apparently, changes in plasma fluorescence did not influence SAF, marker of accumulated tissue AGEs.

Furthermore, our previous studies were performed using glucose containing dialysates. This raised the question if dialysate glucose per se could increase the load of AGE in the body.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate whether PAF and SAF, reflecting the current and accumulated amount of AGEs, respectively, were influenced by the use of either glucose free or glucose-containing dialysate.

Methods

Study design

A longitudinal interventional study was performed at the hemodialysis center at the University Hospital in Umeå.

Demography

During the observation period, 24 patients on chronic HD were included in the study (17 male/ 7 female). The median age was 70.5 years (range 42–85). The median vintage of HD was 52.5 months (range 11–121 months). The main reasons for HD were primary glomerular disorders (n = 5), diabetes nephropathy (n = 5, 2 with diabetes mellitus type 1, and 3 with type 2), polycystic kidney disease (n = 2), hypertension and/or renovascular disease (n = 5), postrenal cause (n = 2) and other or unknown diagnoses (n = 5). The comorbidity of the patients included hypertension (n = 20, 83%) and cardiovascular disease (n = 9, 38%). Five of these patients had suffered from myocardial infarction (21%) and 1 patient from stroke (4%). Lifestyle factors included current or previous tobacco use (15/23, 63% of whom 13% current users; missing information in 1) and alcohol consumption (wine and beer in 38%). All patients were on chronic HD with the median treatment duration/session of 4 h (range 3–5.5 h). Two patients had dialysis with low flux dialyzers (FX10), all others received dialysis with high flux dialyzers (FX80, Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany).

The study was performed as a longitudinal study. Patients were informed consecutively, and those who accepted to participate were included. Exclusion criteria were an ongoing infection and inability to understand information. Patients with diabetes mellitus prone to hypoglycemia would have been excluded if they would have considered participating in the study. No such patient was present. All patients were on chronic HD during standard treatment using a dialysate with a final glucose concentration of 5 mmol/L (Biosol A201.25 glucose 5 and Biosol A301.25 glucose 5, Meda AB, Solna, Sweden). After that, the patients were switched to a glucose-free dialysate (SK-F 209, K+ 2 mmol/l, Ca++ 1,5 mmol/l, Mg++ 0,5 mmol/l, no glucose, Fresenius, Bad Homburg, Germany) for 2 weeks (six sessions). The dialyses within the frame of the study were performed at the same time and same weekday each time (morning dialyses).

Measurements were performed on plasma autofluorescence (PAF) and skin autofluorescence (SAF) both before and after standard HD (ST) at the end of March or the first week of April. The glucose-free dialysate period that began at the first week in May with measurements after 1w of HD (M1) and 2w of HD (M2) with GFD.

Skin-AF was obtained as a median of three measurements along the same forearm at slightly different positions. Measurements were done in a semi-dark environment at room temperature on each occasion. Each patient was his/her own control with the same conditions throughout the study except the dialysate.

AGE reader

The AGE Reader (DiagnOptics Technologies BV, Groningen, The Netherlands) illuminates a skin surface of ~ 4 cm2, guarded against surrounding light, with a light source that mainly provides UV-A light between 350 and 420 nm (peak wavelength 370 nm). Autofluorescence and reflected light from the skin were measured simultaneously using a spectrometer within the instrument. Skin AF was measured in arbitrary units (AU). The arbitrary unit is based on the ratio of the average light intensity per nm in the range between 420 and 600 nm, and the average light intensity per nm in the range between 300 and 420 nm. Version 2.3 of the AGE Reader software was used. The AGE Reader had been validated and was more extensively described in previous studies [24, 25]. A good correlation between the skin AF and the tissue levels of pentosidine, N ε –carboxy-methyl-lysine (CML) and N ε-carboxy-ethyl-lysine (CEL) was found in DM patients and age-matched healthy controls [26].

Plasma autofluorescence (PAF)

Plasma samples were collected before and after HD for the analysis of PAF and albumin concentration. The samples were kept at −70 °C until analysis. Plasma AGEs were quantified using fluorescence with an excitation wavelength of 370 nm and an emission wavelength of 465 nm on a Tecan Genios microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland). Total PAF was measured according to a modified protocol of Schwedler et al. [27]. In brief, plasma samples were diluted 50 times in phosphate buffered saline before measuring fluorescence as described above. The non-protein-bound fluorescence or free plasma fluorescence was determined according to a modified protocol of Wrobel et al. [28]. Thereby, plasma samples were diluted 25 times in 0.15 M trichloroacetic acid, precipitating proteins. After eliminating the precipitate by centrifugation, the fluorescence of the supernatant was measured as above. The bound plasma fraction was calculated as the difference between total and free PAF.

When fluid is removed from the patient by ultrafiltration, cells and larger molecules such as albumin are not dialyzed out of the plasma, leading to hemoconcentration. For adjusting such effects on PAF, The ratio of change in serum albumin after versus before HD was used [29, 30] to adjust PAF after dialysis for such effects.

In this study, we did not investigate other effects of glucose-free dialysis such as potassium removal or levels of triglycerides. Individual dialysates were prescribed and prepared by each dialysis device. No central container for dialysis fluid was used. Bacterial growth and endotoxin content of dialysis water supply are regularly controlled according to European regulations.

Statistical analysis

Paired statistical analyses were performed with the Wilcoxon nonparametric test between the 3 sample periods. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Mean values and standard error of the mean (±) are given. Univariate correlation analyses were performed using the Spearman test (rho) to adjust for the effect of eventual outliers. SPSS statistical software (version 20 SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL) was used for the analyses.

Results

Plasma autofluorescence (PAF)

The various concentrations of PAF are given in Table 1.

There was a significant reduction of all three plasma compounds (Total, free and protein bound PAF) after each dialysis (p < 0.001). Comparing the reduction (Δ PAF after - Δ PAF before dialysis) of the total, free-, protein bound PAF there was no difference in reduction by dialysis at the first measurement (ST) versus M1 (period with glucose free dialysate) or 1 week later (M2).

For total PAF there was no difference between the predialysis values at ST versus M1 and M2 while the M2 values were lower than M1 (p = 0.019). The total- PAF values after HD, adjusted for the effect of ultrafiltration showed a higher value at M1 than at ST (p = 0.015) but a lower value than at M2 (p = 0.001). The value after HD at M2 was not significantly lower than the value at ST (p = 0.058).

For the protein bound PAF there was no difference between the pre-HD concentration at ST versus M1. The concentration at M2 was lower than at ST (p = 0.027). The M2 concentration was also lower than the M1 (p = 0.005). The protein bound non-adjusted and adjusted PAF values after each HD showed the lowest value after 2 weeks using glucose-free dialysate (p < 0.05). The findings can be interpreted that a reduction in protein-bound PAF occurs during the glucose-free dialysate period.

For the free PAF concentration, there was no difference between the ST, M1, and M2 neither the pre-HD values, the differences (before versus after HD) nor the post HD values.

Table 2 shows that the free PAF compound represents approximately 30% of the total PAF both before and after dialysis and the protein bound correspondingly about 70%. The dialysis resulted in a reduction of the total PAF of approximately 15%, the free compound of 20% and the protein bound of 10%. Since the protein bound part was more than twice as large as the free PAF, the reduction of the protein bound part of PAF represented at a median 56% of the overall reduction.

The SAF pre-dialysis values (ST, M1, M2) were not related to the pre-HD values of PAF neither to the total (rho = 0.395, p = 0.056), free (rho = 0.317, p = 0.13) or to the protein bound PAF (rho = 0.22, p = 0.30) nor to the change in PAF that appeared after HD (Total: rho = −0.26, p = 0.27; free: rho = −0.25, p = 0.24; rho = −0.07, p = 0.75).

There was a strong correlation between total, protein-bound and free -PAF values before and after HD and also at different sampling times, such that high values were maintained high and vice versa (rho ≥0.57, p ≤ 0.007). The changes in total, protein-bound and free PAF after dialysis were related to the start value (rho ≥ −0.60, p < 0.005) such that a high initial value resulted in a greater reduction after HD.

There were correlations between total PAF and protein bound PAF (rho >0.74, p < 0.01) and total versus free PAF during the ST and M1 series (rho >0.57, p < 0.005) but not M2 series. No correlation was found between protein-bound PAF and free PAF.

There was no correlation of PAF at the start of the study and age (rho = 0.016, p = 0.938).

Skin autofluorescence (SAF)

SAF was measured before and after HD for the various time points and the difference of SAF before and after dialysis (Table 3).

When the pre-dialysis SAF values at ST, M1 and M2 were compared, there was a significant increase in SAF from the first measurement (ST) to the investigation 1 month later (M2) by a median of 4.8% (p = 0.032). However, when comparing the value achieved after the standard HD (with glucose-containing dialysate) with the pre-dialysis SAF value at M1 (after the first period with glucose free dialysate), there was no significant difference between the values.

There was a nonsignificant (p = 0.61) increase of 1.2% in SAF after the HD with glucose-containing dialysate (ST) comparing with SAF before the same HD. At M1, using glucose-free dialysate, the SAF after HD was reduced by 5.2% (p = 0.002). One week later (M2) the reduction of 1.6% after HD was not significant (p = 0.33). There was no significant difference between the values comparing the reduction (Δ SAF end - SAF start) at M1 versus M2 on glucose free dialysis.

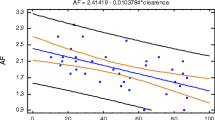

For all three series (ST, M1, M2) there was a strong correlation between SAF values before and after HD and also at different sampling times such as that high values were maintained high and vice versa (rho > 0.68, p < 0.001). The changes in SAF after a dialysis session were not related to the initial values. Skin AF measured at the start of the study (ST) did not correlate with age (rho = 0.255, p = 0.23).

The length of the hemodialysis sessions (at a mean 4.3 h, ±0.6, range 3–5.5) did not correlate with the change in SAF nor the change in any PAF.

Blood glucose was monitored if symptoms appeared. 2 patients, both with diabetes type 2 and insulin treatment developed a hypoglycemia. One of the patients got a bolus injection of glucose, the other was treated with oral dextrose. No patient received or required glucose infusion in parallel to dialysis.

Discussion

In the present investigation of hemodialysis with glucose free hemodialysis (GFD) there appeared a significant decrease, after dialysis, of SAF and total and protein bound PAF concentrations. PAF and SAF reflect the current and accumulated amount of AGEs. SAF is an indirect risk factor for CVD [8, 11], this indicates that the load of protein bound AGEs seems to decrease with a prolonged treatment period with a GFD. Notably, the free part of PAF was not influenced by the GFD. Thus, the difference in outcome in protein bound PAF using GFD versus glucose-containing dialysate may well be due to a fast transfer of the glucose from the dialysate into the blood and extravascular space where a degradation and conversion into glucose degradation products may occur. Initial less tight attachment to various molecules including proteins may result in reversible Amadori products.

The presence of less tight bonds is indicated by the reduction of protein bound PAF in plasma but also by the decrease of SAF after dialysis after glucose-free HD in the present study. The main glucose degradation products are pentosidine and N ε –carboxy-methyl-lysine (CML), that in vitro are water soluble and dialyzable, of a molecular weight of less than 400D. However, both AGEs are considered as protein-bound uremic toxins [31, 32] and poorly removed by HD [33], as confirmed by the present study. Another reason explaining the poor reduction of the free PAF could be an increased production of GDP molecules throughout the dialysis due to the oxidative stress induced by glucose [34]. The more pronounced reduction of SAF by HD at M1 than M2 may indicate that there were more reversibly bound glucose degradation products in the tissue at M1, for example Amadori products. One week later the clearance of such products was less effective, indicating the presence of a lower ratio of reversibly bound AGEs.

The reduction of protein bound PAF levels after 2 weeks of glucose-free dialysis favor the concept of a local extravascular formation of AGEs.

The lack of relation between SAF and PAF, found in this study, is in congruence with others [27, 35].

In contrast to GFD, the use of glucose-containing HD did not change SAF after dialysis, either during the present study or previous studies despite the use of high flux dialyzers [22, 23]. It is discussed that a higher glucose concentration in the dialysate may impair inflammation [17], lipid levels [36], hyperglycemia and conversion of carbohydrates into glucose degradation products and AGEs that subsequently lead to oxidative stress [37].

Hypoglycemia may develop with glucose free dialysate. This risk is most crucial for patients with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus prone to hypoglycemia. Therefore glucose free dialysis seem less suitable for such patients. The use of a glucose infusion in parallel to dialysis may be preventive if the patient does not compensate hypoglycemia by eating.

Conclusions

The present study shows that a glucose free dialysate may result in a significant reduction of SAF, as a marker of AGEs and Amadori products, in contrast to when using glucose-containing dialysate. The protein bound parts of PAF also showed a decrease after 2 weeks. This indicates that it may be possible to hamper or even reverse the deposits of AGEs in tissue. Future longitudinal studies with glucose free dialysate can help to clarify if this leads to a reduction of SAF and in limits the progress of CVD in HD patients.

Abbreviations

- AGE:

-

Advanced glycation end products

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- GFD:

-

Glucose free dialysate

- HD:

-

Haemodialysis

- M1:

-

Measurement after 1 week with glucose-containing dialysate

- M2:

-

Measurement after 2 weeks with glucose-containing dialysate

- PAF:

-

Plasma autofluorescence

- SAF:

-

Skin autofluorescence

- ST:

-

Time of first measurement standard treatment with glucose-containing dialysate

References

Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–305.

Vanholder R, Massy Z, Argiles A, Spasovski G, Verbeke F, Lameire N. Chronic kidney disease as cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(6):1048–56.

Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(12 Suppl):S16–23.

Parfrey PS, Foley RN. The clinical epidemiology of cardiac disease in chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(7):1606–15.

Ritz E. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and natural history of diabetic nephropathy. In: Feehally J, Floege J, Johnson RJ, editors. Comprehensive clinical nephrology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. p. 353–64.

Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Advanced Glycation Endproducts (AGEs). In: Niwa T, editor. Uremic toxins. Hoboken: Wiley; 2012. p. 293–304.

Vanholder R, De Smet R, Glorieux G, Argiles A, Baurmeister U, Brunet P, Clark W, Cohen G, De Deyn PP, Deppisch R, et al. Review on uremic toxins: classification, concentration, and interindividual variability. Kidney Int. 2003;63(5):1934–43.

Meerwaldt R, Hartog JW, Graaff R, Huisman RJ, Links TP, den Hollander NC, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW, Navis G, Gans RO, et al. Skin autofluorescence, a measure of cumulative metabolic stress and advanced glycation end products, predicts mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(12):3687–93.

Godfrey AR. Impact of glucose levels on advanced glycation end products in hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2007;11(3):278–85.

Makita Z, Radoff S, Rayfield EJ, Yang Z, Skolnik E, Delaney V, Friedman EA, Cerami A, Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation end products in patients with diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(12):836–42.

Ueno H, Koyama H, Tanaka S, Fukumoto S, Shinohara K, Shoji T, Emoto M, Tahara H, Kakiya R, Tabata T, et al. Skin autofluorescence, a marker for advanced glycation end product accumulation, is associated with arterial stiffness in patients with end-stage renal disease. Metabolism. 2008;57(10):1452–7.

Goldberg T, Cai W, Peppa M, Dardaine V, Baliga BS, Uribarri J, Vlassara H. Advanced glycoxidation end products in commonly consumed foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(8):1287–91.

Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S, Cai W, Chen X, Pyzik R, Yong A, Striker GE, Vlassara H. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(6):911–6. e912.

Arsov S, Trajceska L, van Oeveren W, Smit AJ, Dzekova P, Stegmayr B, Sikole A, Rakhorst G, Graaff R. The influence of body mass index on the accumulation of advanced glycation end products in hemodialysis patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(3):410.

Parsons FM, Davidson AM. The composition of the dialysis fluid. In: Drukker W, Parsons FM, Maher JF, editors. Replacement of renal function by dialysis. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1979. p. 162–81.

Bergstrom J, Asaba H, Furst P, Oules R. Dialysis, ultrafiltration, and blood pressure. 1976. Blood Purif. 2006;24(2):222–6. discussion 226–231.

Sharma R, Rosner MH. Glucose in the dialysate: historical perspective and possible implications? Hemodial Int. 2008;12(2):221–6.

Wathen RL, Keshaviah P, Hommeyer P, Cadwell K, Comty CM. The metabolic effects of hemodialysis with and without glucose in the dialysate. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31(10):1870–5.

Gutierrez A, Bergstrom J, Alvestrand A. Hemodialysis-associated protein catabolism with and without glucose in the dialysis fluid. Kidney Int. 1994;46(3):814–22.

Burmeister JE, Scapini A, da Rosa MD, da Costa MG, Campos BM. Glucose-added dialysis fluid prevents asymptomatic hypoglycaemia in regular haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(4):1184–9.

Abe M, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Haemodialysis-induced hypoglycaemia and glycaemic disarrays. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(5):302–13.

Graaff R, Arsov S, Ramsauer B, Koetsier M, Sundvall N, Engels GE, Sikole A, Lundberg L, Rakhorst G, Stegmayr B. Skin and plasma autofluorescence during hemodialysis: a pilot study. Artif Organs. 2014;38(6):515–8.

Ramsauer B, Engels G, Arsov S, Hadimeri H, Sikole A, Graaff R, Stegmayr B. Comparing changes in plasma and skin autofluorescence in low-flux versus high-flux hemodialysis. Int J Artif Organs. 2015;38(9):488–93.

Meerwaldt R, Graaff R, Oomen P, Links T, Jager J, Alderson N, Thorpe S, Baynes J, Gans R, Smit A. Simple non-invasive assessment of advanced glycation endproduct accumulation. Diabetologia. 2004;47(7):1324–30.

Koetsier M, Lutgers HL, de Jonge C, Links TP, Smit AJ, Graaff R. Reference values of skin autofluorescence. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12(5):399–403.

Mulder DJ, Water TV, Lutgers HL, Graaff R, Gans RO, Zijlstra F, Smit AJ. Skin autofluorescence, a novel marker for glycemic and oxidative stress-derived advanced glycation endproducts: an overview of current clinical studies, evidence, and limitations. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2006;8(5):523–35.

Schwedler SB, Metzger T, Schinzel R, Wanner C. Advanced glycation end products and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62(1):301–10.

Wrobel K, Garay-Sevilla ME, Nava LE, Malacara JM. Novel analytical approach to monitoring advanced glycosylation end products in human serum with on-line spectrophotometric and spectrofluorometric detection in a flow system. Clin Chem. 1997;43(9):1563–9.

Stegmayr BG, Esbensen K, Gutierrez A, Lundberg L, Nielsen B, Stroemsaeter CE, Wehle B. Granulocyte elastase, beta-thromboglobulin, and C3d during acetate or bicarbonate hemodialysis with Hemophan compared to a cellulose acetate membrane. Int J Artif Organs. 1992;15(1):10–8.

Jones CH, Akbani H, Croft DC, Worth DP. The relationship between serum albumin and hydration status in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2002;12(4):209–12.

Glassock RJ, Massry SG. Uremic Toxins: An Integrated Overview of Definition and Classification. In: Niwa T, editor. Uremic Toxins. Hoboken: Wiley; 2012. p. 1–12.

Miyata T, Ueda Y, Yoshida A, Sugiyama S, Iida Y, Jadoul M, Maeda K, Kurokawa K, de Strihou CY. Clearance of pentosidine, an advanced glycation end product, by different modalities of renal replacement therapy. Kidney Int. 1997;51(3):880–7.

Henle T, Deppisch R, Beck W, Hergesell O, Hansch GM, Ritz E. Advanced glycated end-products (AGE) during haemodialysis treatment: discrepant results with different methodologies reflecting the heterogeneity of AGE compounds. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(8):1968–75.

Miyata T, Maeda K, Kurokawa K, van Ypersele de Strihou C. Oxidation conspires with glycation to generate noxious advanced glycation end products in renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12(2):255–8.

Suliman ME, Heimburger O, Barany P, Anderstam B, Pecoits-Filho R, Rodriguez Ayala E, Qureshi AR, Fehrman-Ekholm I, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P. Plasma pentosidine is associated with inflammation and malnutrition in end-stage renal disease patients starting on dialysis therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(6):1614–22.

Swamy AP, Cestero RV, Campbell RG, Freeman RB. Long-term effect of dialysate glucose on the lipid levels of maintenance hemodialysis patients. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1976;22:54–9.

Luo X, Wu J, Jing S, Yan LJ. Hyperglycemic stress and carbon stress in diabetic glucotoxicity. Aging Dis. 2016;7(1):90–110.

Acknowledgements

We thank Norrlands Njurförening, the County Council Västerbotten (ALF support) and the research fund of Skaraborgs Hospital, Sweden, for financial support.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting our findings are available on request.

Authors’ contributions

The various contributions to the study were by design (BS, RG, AS), applications (BS), clinical fulfillment (BS), data cache (BS, RG, SA), collection and preparation of data (BR, RG, BS, GE), statistical analyses (BR, RG, BS), manuscript preparation primarily (BR) and subsequently (BR, BS, RG, SA, GE) and supervision of PhD student BR (BS). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

RG is founder and stakeholder of Diagnoptics Technologies, the manufacturer of the AGE Reader. None of the other authors reported a conflict of interest with the outcome of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients were informed and gave their consent. The local ethics committee approved the study (The Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå. Dept. of Medical Research, Dnr 08-023 M, March 12, 2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramsauer, B., Engels, G.E., Graaff, R. et al. Skin- and Plasmaautofluorescence in hemodialysis with glucose-free or glucose-containing dialysate. BMC Nephrol 18, 5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-016-0418-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-016-0418-0