Abstract

Background

Glutathione S-transferases play a key role in the detoxification of persistent oxidative stress products which are one of several risks factors that may be associated with many types of disease processes such as cancer, diabetes, and hypertension. In the present study, we characterize the null genotypes of GSTM1 and GSTT1 in order to investigate the association between them and the risk of developing essential hypertension.

Methods

We conducted a case-control study in Burkina Faso, including 245 subjects with essential hypertension as case and 269 control subjects with normal blood pressure. Presence of the GSTT1 and GSTM1 was determined using conventional multiplex polymerase chain reaction followed by gel electrophoresis analysis. Biochemical parameters were measured using chemistry analyzer CYANExpert 130.

Results

Chi-squared test shows that GSTT1-null (OR = 1.82; p = 0.001) and GSTM1-active/GSTT1-null genotypes (OR = 2.33; p < 0.001) were significantly higher in cases than controls; the differences were not significant for GSTM1-null, GSTM1-null/GSTT1-active and GSTM1-null/GSTT1-null (p > 0.05). Multinomial logistic regression revealed that age ≥ 50 years, central obesity, family history of hypertension, obesity, alcohol intake and GSTT1 deletion were in decreasing order independent risk factors for essential hypertension. Analysis by gender, BMI and alcohol showed that association of GSTT1-null with risk of essential hypertension seems to be significant when BMI < 30 Kg/m2, in non-smokers and in alcohol users (all OR ≥ 1.77; p ≤ 0.008). Concerning GSTT1, GSTM1 and cardiovascular risk markers levels in hypertensive group, we found that subjects with GSTT1-null genotype had higher waist circumference and higher HDL cholesterol level than those with GSTT1-active (all p < 0.005), subjects with GSTM1-null genotype had lower triglyceride than those with GSTM1-active (p = 0.02) and subjects with the double deletion GSTM1-null/GSTT1-null had higher body mass index, higher waist circumference and higher HDL cholesterol than those with GSTM1-active/GSTT1-active genotype (all p = 0.01).

Conclusion

Our results confirm that GSTT1-null genotype is significantly associated with risk of developing essential hypertension in Burkinabe, especially when BMI < 30 Kg/m2, in non-smokers and in alcohol users, and it showed that the double deletion GSTM1-null/GSTT1-null genotypes may influence body lipids repartition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

High blood pressure is the most common risk factor for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity worldwide and is thought to be responsible for just under 8 million deaths a year worldwide and nearly 100 million days of disability [1, 2]. In 2000, the number of adults with hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa was estimated at 80 million [3] and in Burkina Faso, more than 18% of the adult population had hypertension in 2013 [4]. High blood pressure is a complex pathology resulting from the interactions of multiple genetic and environmental determinants. It is described in ≈ 90% of cases as essential hypertension when the precise causes of the disease remain poorly understood [5, 6].

There is considerable evidence that oxidative stress resulting from an imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the body’s antioxidant defense systems is involved in the pathophysiology of hypertension [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Several studies have shown that subjects with hypertension and several animal models of hypertension produce an excessive amount of reactive oxygen species [9, 10] and have abnormal levels of antioxidant [13]. Other studies have shown that the blood pressure of mouse models that are genetically deficient in reactive oxygen species generating enzymes is lower than that of their wild-type counterparts [12]. In cultured vascular smooth muscle cells and arteries isolated from hypertensive and hypertensive rats, the production of reactive oxygen species is increased, the redox-dependent signaling is amplified and the bioactivity of the antioxidants is reduced [11]. In addition, there is some evidence to suggest that reactive oxygen species play a key role in the pathophysiological thought to be the cause of hypertension [7, 8]. Reactive oxygen species are highly reactive atoms or molecules with one or more unpaired electron(s) in their external shell such as superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radical formed by the partial reduction of oxygen [14]. Reactive oxygen species have endogenous sources as in the process of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and exogenous sources such as air and water pollution, tobacco, alcohol, heavy or transition metals, drugs, industrial solvents, cooking and radiation, which inside the body are metabolized into free radicals [15]. GSTs are an enzyme superfamily that plays a central role in Phase II of the cellular detoxification process of a diverse group of exogenous and endogenous harmful compounds [16]. They combine reduced glutathione (GSH) to produce a wide variety of lipophilic compounds and having an electrophilic center [17]. This reaction gives a GSH conjugate, often inactive, soluble in water and generally less toxic than the parent compounds such as phenols, plant aflatoxins, superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide [18]. In addition to conventional conjugation reactions, GSTs exhibit glutathione peroxidase activity and catalyze the reduction of organic hydroperoxides such as phospholipids, fatty acids and DNA hydroperoxides to their corresponding alcohols (Hayes et al., 2005). They are also involved in the modulation of signal transduction pathways involved in cell survival and apoptosis, where they control the activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) members [19]. Eight distinct classes of soluble GST in cytoplasmic mammals have been identified named GSTA, GSTM, GSTT, GSTP, GSTS, GSTK, GSTO, GSTZ [20] and Two loci in particular Glutathione S-transferases Mu 1 (GSTM1) and Theta 1 (GSTT1) are the most studied. In human, a significant number of genetic polymorphisms among the GST have been described [16] and individual differences in GST activity are the result of genetic polymorphisms. The most common variant of GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes is homozygous deletion (null genotype) which has been associated with loss of enzymatic activity, oxidative damage and increased vulnerability to cytogenetic [21, 22].

Several cases-controls studies have reported that GSTT1 and/or GSTM1 null genotype were associated to the risk of developing hypertension in some populations, but rather the results are still controversial [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. In this study, we aimed to characterize firstly null variants of GSTM1 and GSTT1 in Burkina Faso and secondly to evaluate the association between them and the risk of developing essential hypertension.

Methods

Study design

The Internal Research Ethics Committee of CERBA/LABIOGENE and National Ethics Committee for Health Research of Burkina Faso approved the protocol of this case-control study. We recruited a total of 514 subjects, including 245 patients with essential hypertension and 269 subjects with normal blood pressure in the cardiology and general consultation departments at Saint Camille Hospital in Ouagadougou and at the Yalgado Ouédraogo University Hospital Center in Ouagadougou. All participants were from the central region of Burkina Faso and resided there.

Essential hypertension was determined by the cardiologist when no secondary cause of blood pressure elevation was present [32]. Subjects with systolic blood pressure less than 130 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure below 80 mmHg, without history of hypertension, and who are not on antihypertensive therapy, were selected as normotensive controls.

Samples and data collection

When a subject met the above selection criteria, he was referred by the cardiologist to the principal investigator who was responsible for clearly explaining the study. Once his consent obtained in a free and transparent manner, using a standardized questionnaire completed throughout the study, data on anthropometric parameters, lifestyle, clinical and biological parameters were collected (see questionnaire in Supplementary file 3). The information collected mainly were age, sex, parents’ ethnicity, occupation, weight, height, waist circumference, lifestyle, blood pressure, personal, family history, electrocardiogram data, cardiac echo-Doppler data and biochemical data.

Blood pressure measurements were performed using a manual aneroid sphygmomanometer and electronic cuffed sphygmomanometer by the cardiologist and the principal investigator. Blood pressure was taken on both arms in a sitting position after at least 20 min of rest. All measurements were made at least twice with a minimum of 5 min between two measurements. Blood pressure values were obtained by averaging the measurements.

Height and weight were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight (Kilogram) by the square of the height (meters). BMI was used to determine obesity when BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, overweight when BMI was between 25 and 30 kg/m2, normal weight when BMI was between 20 and 25 kg/m2 and underweight for a BMI less than 20 kg/m2.

Waist circumference (WC) was determined by measuring the circumference of the abdomen when the subject has minimal breathing using a tape measure. Abdominal obesity was determined in men when WC is greater than 102 cm and in women when it is greater than 88 cm [33].

Participants with a family history of hypertension were defined as those with at least one close family member hypertensive before the age of 60 years.

Each participant also had a venous blood sample of approximately 8 ml in two tubes (EDTA and tube without anticoagulant) for analysis. Sera from anticoagulant-free tubes were directly used for biochemical analyzes in the biochemistry laboratory (CYANExpert 130), and blood white cells from EDTA tubes were placed in cryotubes and stored at − 20 °C in the molecular biology laboratory until extraction of the DNA.

DNA extraction and genotyping

We used standard salt fractionation method as described by Miller and al. in 1988, to isolated genomic DNA from peripheral blood white cells [34]. The purity and concentration of the resulting DNA were determined using Biodrop μLITE (Isogen Life Science, Temse, Belgium) and the extracts were stored at − 20 °C until use.

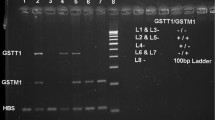

The presence (homozygous +/+ and heterozygous +/−) or absence (homozygous for deletion −/−) of the GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes has been determined according to the method described by Chen and al [35]. Briefly we performed multiplex PCR with the GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystem, USA) in a reaction volume of 25 μL including 10 μL of Master Mix Ampli Taq Gold® (Applied Biosystems, USA), 1 μL of each of the primer pairs of each gene obtained from Biosynthesis, 7 μL of nuclease-free water and 5 μL of DNA. GSTM1 primers were (forward- 5′ GAA CTC CCT GAA AAG CTA AAG C 3′ and reverse- 5′ GTT GGG CTC AAA TAT ACG GTG G 3′), GSTT1 primers were (forward- 5′ TTC CTT ACT GGT CCT CAC ATC TC 3′ and reverse- 5′ TCA CCG GAT CAT GGC CAG CA 3′) and β-globin primers were (forward- 5’CAA CTT CAT CCA CGT TCA CC 3′ and reverse- 5′ GAA GAG CCA AGG ACA GGT AC 3′). All reagents were purchased from Applied Biosystems (ABI, Applera International Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). The amplification program was as follows: an activation phase at 94 °C for 5 min; 40 cycles of a series of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, hybridization at 57 °C for 1 min, elongation at 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72°c for 7 min. PCR products undergo at ethidium bromide-stained 3% agarose gel migration during 45 mn and visualized under UV light at 312 nm using the Geneflash revelation device. Samples in which the GSTM1, GSTT1 and β-globin genes are present yielded 219-bp, 480-bp and 268-bp product respectively; the absence amplifiable GSTM1 or GSTT1 indicates the respective null genotype for each. PCR amplification was considered valid if the sample had a band corresponding to that of β-globin. Supplementary Fig. 1.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 20.0) and Epi Info (Version 6.0).

Following values have been taken into account to determinate sample size using Epi Info Version 6.0: 95% of two-sided confidence level, 80% of power, odds ratio more than 1.7 ratio of controls to cases 1.1, the proportion of control group having null genotypes of GSTM1 and GSTT1 about 30%.

We expressed quantitative variables as mean ± standard deviation and comparison between groups was assessed with Student’s t-test.

Genotypic frequencies were expressed as percentage and comparisons between cases and controls were done with the chi-squared test.

To research factors associated with risk of essential hypertension in our study and possible interactions between them, we performed a multinomial logistic regression analysis (forward stepwise method) by considering hypertensive status as a dependent variable and including the factors we thought were involved in the development of essential hypertension.

For all analyses, difference was statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Quantitative characteristics

The characteristics of the study population are given in Table 1. We included a case group of 245 subjects with a diagnosis of essential hypertension (111 males and 134 females; 50.14 ± 8.22 years old) and a control group of 269 normotensive individuals (129 males and 140 females; 48.69 ± 9.43 years old). Statistical analysis of the distribution by sex and means of age showed no significant differences between cases and controls (p > 0.05), indicating that there is homogeneity between groups.

We found that means of body mass index, waist circumference, serum levels of blood sugar, Total cholesterol, LDL Cholesterol, HDL cholesterol were higher in hypertensive compared to normotensive group and differences were significant (all p < 0.05). These results suggest that many of our patients with essential hypertension are overweight or obese, and that many may also have diabetes and / or hypercholesterolemia, although it is difficult for us to confirm this based on our unique biochemical assay.

We also found that serum levels of Potassium was higher in normotensive group compared to hypertensive (p = 0.03), but there was no significant difference in level of Triglycerides, creatinine, Calcium, Sodium, Magnesium and Chlorine between the two groups (all p > 0.05).

Genetics analysis

The Table 2 shows the distribution of GSTM1 and GSTT1 variants in the study population. A total of 514 subjects (245 cases and 269 controls) were genotyped for the deletion genotype of two GST isoforms. In the general study population, we found that the frequency of GSTM1-active and GSTT1-active were 71.60 and 37.94% respectively; those of GSTM1-null and GSTT1-null were 28.40 and 62.06% respectively. Based on the ratio controls to cases, odds ratio, and frequencies of GSTM1-null and GSTT1-null, the genetic power calculator indicated that the sample size is large enough to perform a case-control analysis with 85% power for GSTT1, those of GSTM1 is less than 40%.

When we compared these frequencies between cases and controls, we found that subjects with GSTT1-null genotype (69.39% versus 55.39%; OR = 1.82; p = 0.001) and GSTM1-active/GSTT1-null genotype (56.32% versus 39.03%; OR = 2.33; p < 0.001) were more present in case group than controls and difference between the two group was significant. But we didn’t find a significant difference between cases and controls concerning GSTM1-null genotype (25.30% versus 31.23%; OR = 0.74; p = 0.14) and the double deletion GSTM1-null/GSTT1-null (13.06% versus 16.73%; OR = 1.26; p = 0.45).

The Table 3 presents multinomial logistic regression for essential hypertension risk factors in our study population to obtain adjusted odds ratio values and confidence intervals. We found that advanced age (≥ 50 years; OR = 5.33; p < 0.001), central obesity (OR = 4.80; p < 0.001), family history of hypertension (OR = 4.61; p < 0.001), obesity (OR = 3.95; p = 0.001), alcohol intake (OR = 2.16; p < 0.001) and GSTT1 deletion (OR = 1.81; p = 0.001) were in decreasing order independent risk factors for developing essential hypertension in our general study population.

Considering BMI, alcohol and smoking difference in essential hypertension, we further stratified genotyping results by BMI, smoking and alcohol status (Table 4). Interestingly results showed that association between GSTT1-null and essential hypertension seems to be significant when BMI < 30 Kg/m2 (OR = 1.77; p = 0.008), in non-smokers (OR = 1.86; p = 0.003) and in alcohol users (OR = 2.26; p = 0.007).

In addition, concerning GSTT1, GSTM1 and cardiovascular risk markers levels in hypertensive group we compared the average of cardiovascular risk markers between the GSTM1 and GSTT1 null and active genotypes. We found that hypertensive individuals with GSTM1-null genotype had a lower average triglyceride than GSTM1-active genotypes; GSTT1-null genotype had a higher average waist circumference and HDL cholesterol than GSTT1-active genotype and the double deletions GSTM1-null/GSTT1-null have higher body mass index, higher waist circumference and higher HDL cholesterol than GSTM1-active/GSTT1-active (data not shown). Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

There is increasing interest in the role of Glutathione S-transferase polymorphism as a contributory factor to oxidative stress and consequently to cellular damage and physiological anomalies such us cancers, diabetes, cardiovascular disorders [36]. The present study aimed to characterize firstly the null genotype of GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes in Burkina Faso and secondly to analyzes a possible association between them and the risk of developing essential hypertension. Our study showed in the control group that the frequency of GSTM1-null and GSTT1-null were 31.23 and 55.76% respectively. There were several studies about GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletion and some diseases process, so Fig. 1 summarizes the frequencies of the GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletion in some African countries [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

In our study we analyzed also the relationship between Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 genes deletion and their connection with essential hypertension and any complications that may have accompanied this disease in Burkina Faso. Association between GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms and cardiovascular disorders has long been studied. Some studies have shown that GSTM1 [25, 26, 47, 48] and/or GSTT1 [26, 27, 48,49,50,51] were associated with essential hypertension risk, other authors have shown that only the double deletion GSTM1/GSTT1 was associated with essential hypertension risk, and other failed to confirm any association [29]. The Table 5 summarize previous associations studies of GSTM1 and GSTT1 with risk of hypertension, specifies the size and type of population as well as the type of PCR and the main results obtained. In the present study, we showed that the frequency of GSTT1-null genotype was significantly higher in essential hypertension group than control group, indicating a possible association between GSTT1 and risk of developing essential hypertension with a power of more than 85%. We failed to replicate association of essential hypertension with GSTM1-null genotype and the double deletion GSTM1-null/GSTT1-null even if GSTM1-null frequencies only give us a power of less than 40%.

Essential hypertension is a complex disease, with many risk factors [52], and there is growing evidence that gene interactions with environmental factors may increase susceptibility to essential hypertension [53], so that certain genetic variants have only a significant effect in specific populations. In our study we found that alcohol use, lack of sport, overweight, obesity, central obesity, and family history of hypertension were factors that increased the risk of developing essential hypertension in our study population. In addition, we performed a stratified analysis by BMI, alcohol use and smoking status of the association between GSTM1, GSTT1 variants and essential hypertension; The results showed that association between GSTT1-null and essential hypertension seems to be significant especially in alcohol users but independent of obesity and smoking even if some of the comparisons do not have enough samples. The present work confirms that the deletion of GSTT1 may increase the risk of developing essential hypertension, and this is partly related to the antioxidant activity of the GST enzyme. In fact, Nitric oxide (released by the endothelium) plays a major role in arterial relaxation and is rapidly degraded by the oxygen-derived free radical superoxide anion [54], the presence of which largely depends on the activity of the GST enzyme. Therefore, GST variants may influence nitric oxide bioavailability and subsequently may influence the individual susceptibility to essential hypertension.

In addition, we also compared in hypertensive group, means of certain cardiovascular risk markers between null and active genotypes of GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes. We found significantly lower triglyceride in GSTM1-null genotype compared to GSTM1-active; we also observed in GSTT1-null subjects, significantly higher waist circumference and serum HDL cholesterol compared to GSTT1-active genotype. The double deletion GSTM1-null/GSTT1-null was associated with body mass index, waist circumference and serum HDL cholesterol increasing. These results suggest a probable association of Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 genes deletion with body fat and serum cholesterol level. There is not a lot of study about these association, while Almoshabek and al. reported in young age Saudis that frequencies of GSTM1-active/GSTT1-null (OR = 2.70; p < 0.001) and GSTM1-null/GSTT1-null (OR = 2.43, p = 0.018) were significantly higher in overweight/obese as compared to normal weight [55]. Our results are in accordance with those of Afrand and al. in Zoroastrian females (Iran), that reported significantly lower HDL cholesterol in GSTT1-null as compared to GSTT1-active genotype in metabolic syndrome [56], and Khalilzadeh and al. that reported higher levels of triglyceride, fasting blood sugar, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, body mass index and HDL cholesterol in patients with type 2 diabetes with GSTT1-null genotype than in those with the GSTT1-active genotypes [57].

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests the significant association between GSTT1-null genotype and the risk of developing essential hypertension in Burkinabe population, therefore the important role of oxidative stress in the development of essential hypertension. The study also suggests that the double deletion GSTT1-null/GSTM1-null may affect body lipids repartition in hypertensive. However large-scale study will be necessary to fully comprehend the role of GSTM1 and GSTT1 variant in the development of essential hypertension.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated in this study is available from NCBI Nucleotide under the accession number LC517160.1.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CERBA:

-

Pietro annigoni biomolecular research center

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic

- GSTA :

-

Glutathione S-transferases alpha

- GSTK :

-

Glutathione S-transferases kappa

- GSTM1 :

-

Glutathione S-transferases mu 1

- GSTO :

-

Glutathione S-transferases omega

- GSTP :

-

Glutathione S-transferases pi

- GSTS :

-

Glutathione S-transferases sigma

- GSTT1 :

-

Glutathione S-transferases theta 1

- GSTZ :

-

Glutathione S-transferases zeta

- HDL-c:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LABIOGENE:

-

Laboratory of molecular biology and genetics

- LDL-c:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MD:

-

Means difference

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- ROS:

-

Reactive Oxygen Species

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for the social sciences

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

References

Redon J, Tellez-Plaza M, Orozco-Beltran D, Gil-Guillen V, Pita Fernandez S, Navarro-Perez J, Pallares V, Valls F, Fernandez A, Perez-Navarro AM, et al. Impact of hypertension on mortality and cardiovascular disease burden in patients with cardiovascular risk factors from a general practice setting: the ESCARVAL-risk study. J Hypertens. 2016;34(6):1075–83.

Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1513–8.

Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, She J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365(9455):217–23.

Soubeiga JK, Millogo T, Bicaba BW, Doulougou B, Kouanda S. Prevalence and factors associated with hypertension in Burkina Faso: a countrywide cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):64.

Carretero OA, Oparil S. Essential hypertension. Part I: definition and etiology. Circulation. 2000;101(3):329–35.

Messerli FH, Williams B, Ritz E. Essential hypertension. Lancet. 2007;370(9587):591–603.

Klahr S. Urinary tract obstruction. Semin Nephrol. 2001;21(2):133–45.

Rodrigo R, Rivera G. Renal damage mediated by oxidative stress: a hypothesis of protective effects of red wine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33(3):409–22.

Stojiljkovic MP, Lopes HF, Zhang D, Morrow JD, Goodfriend TL, Egan BM. Increasing plasma fatty acids elevates F2-isoprostanes in humans: implications for the cardiovascular risk factor cluster. J Hypertens. 2002;20(6):1215–21.

Tanito M, Nakamura H, Kwon YW, Teratani A, Masutani H, Shioji K, Kishimoto C, Ohira A, Horie R, Yodoi J. Enhanced oxidative stress and impaired thioredoxin expression in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6(1):89–97.

Touyz RM. Reactive oxygen species, vascular oxidative stress, and redox signaling in hypertension: what is the clinical significance? Hypertension. 2004;44(3):248–52.

Gavazzi G, Banfi B, Deffert C, Fiette L, Schappi M, Herrmann F, Krause KH. Decreased blood pressure in NOX1-deficient mice. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(2):497–504.

Briones AM, Touyz RM. Oxidative stress and hypertension: current concepts. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12(2):135–42.

Ray PD, Huang B-W, Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24(5):981–90.

Phaniendra A, Jestadi DB, Periyasamy L. Free radicals: properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J Clin Biochem : IJCB. 2015;30(1):11–26.

Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88.

Mannervik B, Danielson UH. Glutathione transferases--structure and catalytic activity. CRC critical reviews in biochemistry. 1988;23(3):283–337.

Itzhaki H, Woodson W. Characterization of an ethylene-responsive glutathione S-transferase gene cluster in carnation. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:43–58.

Singh S. Cytoprotective and regulatory functions of glutathione S-transferases in cancer cell proliferation and cell death. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;75(1):1–15.

Strange RC, Spiteri MA, Ramachandran S, Fryer AA. Glutathione-S-transferase family of enzymes. Mutat Res. 2001;482(1–2):21–6.

Hayes JD, Strange RC. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms and their biological consequences. Pharmacology. 2000;61(3):154–66.

Norppa H. Cytogenetic biomarkers and genetic polymorphisms. Toxicol Lett. 2004;149(1–3):309–34.

Delles C, Padmanabhan S, Lee WK, Miller WH, McBride MW, McClure JD, Brain NJ, Wallace C, Marcano AC, Schmieder RE, et al. Glutathione S-transferase variants and hypertension. J Hypertens. 2008;26(7):1343–52.

Bessa SS, Ali EM, Hamdy SM. The role of glutathione S- transferase M1 and T1 gene polymorphisms and oxidative stress-related parameters in Egyptian patients with essential hypertension. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(6):625–30.

Capoluongo E, Onder G, Concolino P, Russo A, Santonocito C, Bernabei R, Zuppi C, Ameglio F, Landi F. GSTM1-null polymorphism as possible risk marker for hypertension: results from the aging and longevity study in the Sirente geographic area (ilSIRENTE study). Clin Chim Acta. 2009;399(1–2):92–6.

Borah PK, Shankarishan P, Mahanta J. Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 gene polymorphisms and risk of hypertension in tea garden workers of north-East India. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011;15(11):771–6.

Polimanti R, Piacentini S, Lazzarin N, Re MA, Manfellotto D, Fuciarelli M. Glutathione S-transferase variants as risk factor for essential hypertension in Italian patients. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;357(1–2):227–33.

Wang R, Wang Y, Wang J, Yang K. Association of glutathione S-transferase T1 and M1 gene polymorphisms with ischemic stroke risk in the Chinese Han population. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7(18):1420–7.

Hussain K, Salah N, Hussain S, Hussain S. Investigate the role of glutathione S Transferase (GST) polymorphism in development of hypertension in UAE population. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14(8):479–82.

Rong S-L, Zhou X-D, Wang Z-K, Wang X-L, Wang Y-C, Xue C-S, Li B. Glutathione S-Transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms and hypertension risk: an updated meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2018.

Lee SH, Park E, Park YK. Glutathione S-Transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms and susceptibility to oxidative damage in healthy Korean smokers. Ann Nutr Metab. 2010;56(1):52–8.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021–104.

Zhang C, Rexrode KM, van Dam RM, Li TY, Hu FB. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women. Circulation. 2008;117(13):1658–67.

Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(3):1215.

Chen CL, Liu Q, Pui CH, Rivera GK, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro R, Evans WE, Relling MV. Higher frequency of glutathione S-transferase deletions in black children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1997;89(5):1701–7.

Liguori I, Russo G, Curcio F, Bulli G, Aran L, Della-Morte D, Gargiulo G, Testa G, Cacciatore F, Bonaduce D, et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:757–72.

Masimirembwa CM, Dandara C, Sommers DK, Snyman JR, Hasler JA. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P4501A1, microsomal epoxide hydrolase, and glutathione S-transferases M1 and T1 in Zimbabweans and Venda of southern Africa. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8(1):83–5.

Wild CP, Yin F, Turner PC, Chemin I, Chapot B, Mendy M, Whittle H, Kirk GD, Hall AJ. Environmental and genetic determinants of aflatoxin-albumin adducts in the Gambia. Int J Cancer. 2000;86(1):1–7.

Dandara C, Sayi J, Masimirembwa CM, Magimba A, Kaaya S, De Sommers K, Snyman JR, Hasler JA. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 1A1 (Cyp1A1) and glutathione transferases (M1, T1 and P1) among Africans. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40(9):952–7.

Hamdy SI, Hiratsuka M, Narahara K, Endo N, El-Enany M, Moursi N, Ahmed MSE, Mizugaki M. Genotype and allele frequencies of TPMT, NAT2, GST, SULT1A1 and MDR-1 in the Egyptian population. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(6):560–9.

Ouerhani S, Tebourski F, Slama MR, Marrakchi R, Rabeh M, Hassine LB, Ayed M, Elgaaied AB. The role of glutathione transferases M1 and T1 in individual susceptibility to bladder cancer in a Tunisian population. Ann Hum Biol. 2006;33(5–6):529–35.

Buchard A, Sanchez JJ, Dalhoff K, Morling N. Multiplex PCR detection of GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 gene variants: simultaneously detecting GSTM1 and GSTT1 gene copy number and the allelic status of the GSTP1 Ile105Val genetic variant. J Mol Diagn : JMD. 2007;9(5):612–7.

Fujihara J, Yasuda T, Iida R, Takatsuka H, Fujii Y, Takeshita H. Cytochrome P450 1A1, glutathione S-transferases M1 and T1 polymorphisms in Ovambos and Mongolians. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009;11(Suppl 1):S408–10.

Santovito A, Burgarello C, Cervella P, Delpero M. Polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 1A1, glutathione s-transferases M1 and T1 genes in Ouangolodougou (northern Ivory Coast). Genet Mol Biol. 2010;33(3):434–7.

Piacentini S, Polimanti R, Porreca F, Martinez-Labarga C, De Stefano GF, Fuciarelli M. GSTT1 and GSTM1 gene polymorphisms in European and African populations. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(2):1225–30.

Kassogue Y, Quachouh M, Dehbi H, Quessar A, Benchekroun S, Nadifi S. Effect of interaction of glutathione S-transferases (T1 and M1) on the hematologic and cytogenetic responses in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. Med Oncol. 2014;31, 47(7).

Han JH, Lee HJ, Cho MR, Yun KE, Choi HJ, Kang M-H. Association between glutathione S-transferase (GST) M1 and T1 Polymorphisms and subclinical hypertension in Korean population. FASEB J. 2011;25(1_supplement):782.788.

Abbas S, Raza ST, Chandra A, Rizvi S, Ahmed F, Eba A, Mahdi F. Association of ACE, FABP2 and GST genes polymorphism with essential hypertension risk among a north Indian population. Ann Hum Biol. 2015;42(5):461–9.

Marinho C, Alho I, Arduino D, Falcao LM, Bras-Nogueira J, Bicho M. GST M1/T1 and MTHFR polymorphisms as risk factors for hypertension. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353(2):344–50.

Lee B-K, Lee SJ, Joo JS, Cho K-S, Kim NS, Kim H-J. Association of Glutathione S-transferase genes (GSTM1 and GSTT1) polymorphisms with hypertension in lead-exposed workers. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2012;8(2):203–8.

Petrovic D, Peterlin B. GSTM1-null and GSTT1-null genotypes are associated with essential arterial hypertension in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(7–8):574–7.

Kotchen TA. Obesity-related hypertension: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(11):1170–8.

Kuneš J, Zicha J. Developmental windows and environment as important factors in the expression of genetic information: a cardiovascular physiologist's view. Clin Sci. 2006;111(5):295–305.

Schulz E, Gori T, Münzel T. Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:665.

Almoshabek HA, Mustafa M, Al-Asmari MM, Alajmi TK, Al-Asmari AK. Association of glutathione S-transferase GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletion polymorphisms with obesity and their relationship with body mass index, lipoprotein and hypertension among young age Saudis. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;5:2048004016669645.

Afrand M, Bashardoost N, Sheikhha MH, Afkhami-Ardekani M. Association between glutathione S-Transferase GSTM1-T1 and P1 polymorphisms with metabolic syndrome in Zoroastrians in Yazd, Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44(5):673–82.

Khalilzadeh S, Afrand M, Froozan-Nia SK, Sheikhha MH. Evaluation of glutathione S-transferase T1 (GSTT1) deletion polymorphism on type 2 diabetes mellitus risk in a sample of Yazdian females in Yazd, Iran. Electron Physician. 2014;6(3):856–62.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all participants in this study. A deep gratitude to all the staff of Saint Camille Hospital of Ouagadougou (HOSCO) and Biomolecular Research Center Pietro Annigoni (CERBA) for technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) through the “Programme d’appui et de développement des centres d’excellence régionaux” (PACERII) and “Centre national de l’Information, de l’Orientation Scolaire et Professionnelle, et des Bourses” (CIOSPB) especially for researcher life stipend. Financial support for reagents and consumables was provided by Italian Episcopal Conference (CEI). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: JKK, HM and JS. Sampling and Laboratory analysis: APS, HKS, SY, DS, ITK, PB, IN, ETHDA and JKK. Statistical analysis and interpretation of data: HKS, APS, ATY, DT. Drafting of the manuscript: FWD, HKS, APS, BMN, AKO and JS. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AKO, HKS, DT, FWD, BMN, HM, JKK, PZ and JS. Administrative, technical, and material support: FWD, ATY, JKK and JS. Study supervision: JKK, HM, PZ and JS. The Corresponding Author declare that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study has been approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research of Burkina Faso.CERS20186065, 6 June 2018, retrospectively registered. Free and written consent was obtained from all participants of this study. The anonymity and confidentiality of the patients were respected as stated in the IRB (Institutional Review Board) protocol.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Locations of GSTM1, GSTT1 and β-globin genes and corresponding bands in electrophoresis gel. This file shows locations of GSTM1, GSTT1 and β-globin genes on chromosomes and corresponding bands. The number 1 through 19 represents individual sample and M represents Molecular weight marker. The strategy to identify presence or absence of GSTM1or GSTT1was as followed: to validate a PCR product (corresponding to a sample), we must have a band corresponding to β-globin and presence or absence of GSTM1 or GSTT1 was indicated respectively by the presence or absence of bands corresponding for each gene.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Distribution of cardiovascular risk markers according to GSTM1 and GSTT1 variants in hypertensive group. This table show and compare average of cardiovascular risk markers such as BMI, WC, serum level of blood sugar, TC, HDL-c, LDL-c and Triglycerides according to GSTM1 and GSTT1 variants in hypertensive group.

Additional file 3 Data collection.

Information sheet and questionnaire. This file shows the fact sheets used to explain the study during the recruitment of the participants and the questionnaire which served for the data collection.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sombié, H.K., Sorgho, A.P., Kologo, J.K. et al. Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 genes deletion polymorphisms and risk of developing essential hypertension: a case-control study in Burkina Faso population (West Africa). BMC Med Genet 21, 55 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-020-0990-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-020-0990-9