Abstract

Background

Muscular dystrophies are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by variable degrees of progressive muscle degeneration and weakness. There is a wide variability in the age of onset, symptoms and rate of progression in subtypes of these disorders. Herein, we present the results of our study conducted to identify the pathogenic genetic variation involved in our patient affected by rigid spine muscular dystrophy.

Case presentation

A 14-year-old boy, product of a first-cousin marriage, was enrolled in our study with failure to thrive, fatigue, muscular dystrophy, generalized muscular atrophy, kyphoscoliosis, and flexion contracture of the knees and elbows. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was carried out on the DNA of the patient to investigate all coding regions and uncovered a novel, homozygous missense mutation in SEPN1 gene (c. 1379 C > T, p.Ser460Phe). This mutation has not been reported before in different public variant databases and also our database (BayanGene), so it is classified as a variation of unknown significance (VUS). Subsequently, it was confirmed that the novel variation was homozygous in our patient and heterozygous in his parents. Different bioinformatics tools showed the damaging effects of the variant on protein. Multiple sequence alignment using BLASTP on ExPASy and WebLogo, revealed the conservation of the mutated residue.

Conclusion

We reported a novel homozygous mutation in SEPN1 gene that expands our understanding of rigid spine muscular dystrophy. Although bioinformatics analyses of results were in favor of the pathogenicity of the mutation, functional studies are needed to establish the pathogenicity of the variant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Muscular dystrophies are a group of disorders with heterogeneous clinical, genetic, and biochemical presentation. They are usually recognized by variable degrees of progressive muscle degeneration and weakness affecting limb, axial, and facial muscles. In some types of these disorders, muscles of the respiratory system and heart, as well as the swallowing process can be involved. Rarely, other tissues and organs, including brain, inner ear, eyes, or skin are also affected. There is a wide variability in the age of onset, symptoms and rate of progression in different forms of these disorders [1,2,3].

During the past decade, muscular dystrophies have extensively been studied. These advancements have been largely due to the breakthroughs developed in molecular genetics techniques, which have paved the way for the identification of the genetic and molecular basis of many of these disorders, improvements in the standards of care, and novel treatment approaches. Currently, performing molecular genetic diagnosis is very useful for establishment of phenotype-genotype correlations, pre-marital genetic counseling, prenatal diagnosis, and disease prognosis as well as identification of new treatments for these disorders [4,5,6,7,8,9].

Since identification of the exact function of genes involved in muscular dystrophies, as well as the pathological mechanisms and phenotypic consequences of mutations may shed light on therapeutic strategies for these disorders, the objective of our study was to find the genetic cause of muscular dystrophy in our patient and report the associated observed clinical presentations.

Case presentation

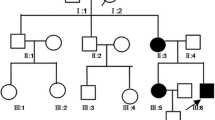

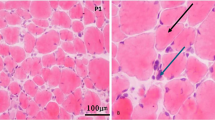

A 14-year-old boy (height = 140 cm, weight = 18 kg) from Fars province, southern Iran, who was born to first-cousin parents without family history of any genetic disorders, was referred to our center with failure to thrive, fatigue, muscular dystrophy, generalized muscular atrophy, kyphoscoliosis, and flexion contracture of the knees and elbows (Fig. 1). His motor symptoms started at the age of four years with frequent episodes of falling down that had progressed in subsequent years. There were no other family members with similar signs or symptoms. He walked at the age of 11 months and had no motor milestone delay. He had two previous admissions to the pediatric intensive care unit due to pneumonia and respiratory distress. The patient had nasal speech and sleep apnea and was under treatment with BiPAP breathing machine. By the age of 12, he was noted to have scoliosis requiring bracing.

On physical examination, the patient was cachectic with generalized muscular atrophy. Decreased muscle power in the shoulder-girdle muscles, foot extensors and limb muscles (4/5 MRC muscle scale) was noted. He also had pes cavus and contracture of both knees and elbows. He was also found to have severe spine rigidity with a chin-sternum distance of 15 cm.

Transthoracic echocardiography was only notable for mild pulmonary hypertension and mild tricuspid regurgitation. Pulmonary function testing revealed a FEV1 of 35% and FVC of 32% of the predicted values.

Serum calcium and phosphorus levels were 8.2 and 3.1 mg/dL, respectively. The patient had abnormally high levels of creatine phosphokinase (CPK) (340 U/L) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (1200 U/L).

Nerve conduction study was normal. However, needle electromyography (EMG) examination revealed myopathic changes in deltoid, biceps, tibialis anterior, and rectus femoris muscles, in favor of Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy.

To identify the mutated gene involved, whole-exome sequencing (WES) was used on genomic DNA extracted from EDTA blood of the patient. Next generation sequencing (NGS) was carried out on an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform to investigate all coding regions and their boundaries. WES details of coverage and number of reads are provided in Table 1. NGS data were analyzed using different bioinformatics tools and databases [10]. NGS data identified a novel, homozygous missense mutation in SEPN1 gene (chr1:25812784, NM_020451.2: exon:10, c. 1379 C > T, p.Ser460Phe). This mutation has not been reported before in different public variant databases and also our database (BayanGene), so it is classified as a variation of unknown significance (VUS). To confirm the novel mutation identified in our patient, Sanger sequencing was performed using primers covering the mutated exon as follows:

F-SELE: 5’-GCACACACTACAGACTCAGC-3′ and.

R-SELE: 5’-GGAAGACACTTGGTCAAGGTTAC-3′ (443 bp).

Sanger sequencing confirmed the identified mutation in SEPN1 in proband as homozygous (T/T). His mother, father and brother were confirmed to be heterozygous (C/T), and his sister homozygous for the wildtype allele (C/C) (Fig. 2).

In order to predict the conservation of the mutated residue, we used different bioinformatics tools, including the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST BLASTP ver 2.2.31+) on ExPASy (available from: https://web.expasy.org/cgi-bin/blast/BLAST.pl) and WebLogo (https://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi).

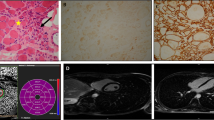

Bioinformatics analysis predicted that this mutation is damaging and can affect the proper function of the protein (Table 2). In addition, multiple protein sequence alignment revealed conservation of the most residues of SEPN1 across different species (Fig. 3a and b). Serine residue is conserved among studied species (Fig. 3a). The frequency of serine in this position is more than that for glycine and proline—only these two amino acids replace serine in other species. Since phenylalanine residue is not among these frequent amino acids, the replacement of serine with phenylalanine is predicted to be deleterious.

a: Graphical representation of amino acid multiple sequence alignment among different species. It shows degree of conservation for amino acids 447–465 of SEPN1 protein. Position 460 (serine) indicates the mutated residue in our study. It has middle conservation degree (2 bits) and also shows that it is replaced by two other amino acids, i.e., glycine and proline in other species but not by phenylalanine. A logo represents the height of each letter proportional to the observed frequency of the corresponding amino acid. The overall height of each stack is proportional to the sequence conservation, measured in bits, at that position. The maximum sequence conservation per site is log2 20 ≈ 4.32 bits for proteins. The protein sequence alignment was performed for the following species: Homo sapiens (Q9NZV5), Gorilla gorilla gorilla (G3R759), Pongo abelii (H2N8I1), Papio anubis (A0A2I3MR13), Rhinopithecus roxellan (A0A2K6RVS9), Sus scrofa (A1E950), Bos taurus (F1MD36), Myotis lucifugus (G1P3X6), Dipodomys ordii (A0A1S3GIF9), Equus caballus (F7BM99), Loxodonta africana (G5E785), and Mus musculus (D3Z2R5). b: Multiple protein sequence alignment of SEPN1 across different kingdoms

Discussion and conclusion

Desmin-related myopathies (DRM) are a group of muscular disorders with heterogeneous clinical presentation and genetic basis, characterized by intrasarcoplasmic desmin aggregation. It has been found that around 30% of DRM are resulted from impaired desmin gene. The impairment in the structure and subsequent accumulation of desmin result in spinal rigidity, limitation of neck and trunk flexion, progressive scoliosis, early notable limited flexion of the lumbar and cervical spine, which ultimately lead to loss of the spine and thoracic cage movements [11].

Rigid spine muscular dystrophy-1 and myopathy, congenital, with fiber-type disproportion (CFTD) result from disease-causing mutations in SEPN1 gene (606210), located on chromosome 1p36, which encodes selenoprotein N, a glycoprotein found within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [12].

Selenoproteins, which contain selenocysteine residue, are vital for a wide range of biological pathways [13, 14]. Twenty-five selenoprotein-encoding genes have been identified in human genome [15]. The SEPN1 contains a single selenocysteine residue and has an ER-addressing and -retention signal, indicating its localization within the ER [16, 17]. High level of expression of SEPN1 has been found in several human fetal tissues, including muscles. However, the level of expression is lower in adult tissues, indicating its key role during early stages of embryogenesis, in early development and in cell proliferation [17, 18]. SEPN1 has a Ca2+-binding domain that is involved in the biochemical processes regulating the release of intracellular calcium. This protein is essentially involved in oxidation and reduction reactions, mainly on calcium pumps, modifying the regulation of calcium in ER [19]. Calcium homeostasis is crucial for normal development and differentiation of muscle. Therefore, SEPN1 protein is a vital component in the process of muscle fiber formation and fiber specification [20].

In fact, supporting evidence suggests that selenium, among all its biological roles, is also influential on the normal physiologic state of striated muscles. For instance, selenium deficiency leads to acquired cardiomyopathy [21] and white muscle disease [22]. Likewise, the SEPN1 mutations are associated with muscular dystrophies.

So far, four autosomal-recessive neuromuscular disorders, collectively regarded as SEPN1-related myopathies (SEPN-RM), have been identified [23]. Those include rigid spine muscular dystrophy (RSMD1) [24, 25], the classical form of multiminicore disease (MmD) [23], desmin-related myopathy with Mallory-body like inclusions (MB-DRM) [26], and CFTD [27]. Patients with SEPN-RM present with similar clinical findings, mainly early-onset hypotonia and muscular atrophy, particularly in axial musculature, along with ensuing scoliosis, neck weakness, and spinal rigidity. In patients with impaired respiratory ventilation, fatal prognosis is also expected [28]. However, the disease onset, clinical course and outcome of patients can be very variable [29].

The first SEPN1 mutation related to a human genetic disorder was found in 2001 in patients affected by congenital RSMD [24]. Over the recent years, various pathogenic and non-pathogenic variations have been identified across SEPN1 [30, 31]. The initial approach for a reliable clinical diagnosis of these disorders is doing a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of muscles, and measuring the growth hormone level, metabolic and muscular serum markers, and performing electrodiagnostic studies and echocardiography [32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

In conclusion, we identified a novel SENP1 mutation, which is predicted to be deleterious due to high damaging scores extracted from various bioinformatics software, conservation of amino acid in studied position, confirmation of mutation in the family, and absence of the mutation in our databases (1000 Iranian Genome).

Abbreviations

- CFTD:

-

Congenital fiber-type disproportion

- CPK:

-

Creatine phosphokinase

- DRM:

-

Desmin-related myopathies

- EMG:

-

Electromyography

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MB-DRM:

-

Desmin-related myopathy with Mallory-body like inclusions

- MmD:

-

Multiminicore disease

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- RSMD1:

-

Rigid spine muscular dystrophy

- SEPN-RM:

-

SEPN1-related myopathies

- VUS:

-

Variation of unknown significance

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

References

Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359(9307):687–95.

Lisi MT, Cohn RD. Congenital muscular dystrophies: new aspects of an expanding group of disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772(2):159–72.

Muntoni F, Torelli S, Brockington M. Muscular dystrophies due to glycosylation defects. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(4):627–32.

Darin N, Tulinius M. Neuromuscular disorders in childhood: a descriptive epidemiological study from western Sweden. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10(1):1–9.

Norwood FL, Harling C, Chinnery PF, Eagle M, Bushby K, Straub V. Prevalence of genetic muscle disease in northern England: in-depth analysis of a muscle clinic population. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 11):3175–86.

Mercuri E, Muntoni F. The ever-expanding spectrum of congenital muscular dystrophies. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(1):9–17.

Guglieri M, Straub V, Bushby K, Lochmuller H. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21(5):576–84.

Bushby K, Finkel R, Birnkrant DJ, Case LE, Clemens PR, Cripe L, Kaul A, Kinnett K, McDonald C, Pandya S, et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary care. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(2):177–89.

Wang CH, Bonnemann CG, Rutkowski A, Sejersen T, Bellini J, Battista V, Florence JM, Schara U, Schuler PM, Wahbi K, et al. Consensus statement on standard of care for congenital muscular dystrophies. J Child Neurol. 2010;25(12):1559–81.

Dastsooz H, Nemati H, Fard MAF, Fardaei M, Faghihi MA. Novel mutations in PANK2 and PLA2G6 genes in patients with neurodegenerative disorders: two case reports. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18(1):87.

Dubowitz V. Rigid spine syndrome: a muscle syndrome in search of a name. Proc R Soc Med. 1973;66(3):219–20.

Ferreiro A, Ceuterick-de Groote C, Marks JJ, Goemans N, Schreiber G, Hanefeld F, Fardeau M, Martin JJ, Goebel HH, Richard P, et al. Desmin-related myopathy with Mallory body-like inclusions is caused by mutations of the selenoprotein N gene. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(5):676–86.

Hatfield DL, Tsuji PA, Carlson BA, Gladyshev VN. Selenium and selenocysteine: roles in cancer, health, and development. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(3):112–20.

Rayman MP. Selenium and human health. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1256–68.

Kryukov GV, Castellano S, Novoselov SV, Lobanov AV, Zehtab O, Guigó R, Gladyshev VN. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300(5624):1439–43.

Gladyshev VN, Arnér ES, Berry MJ, Brigelius-Flohé R, Bruford EA, Burk RF, Carlson BA, Castellano S, Chavatte L, Conrad M. Selenoprotein gene nomenclature. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(46):24036–40.

Petit N, Lescure A, Rederstorff M, Krol A, Moghadaszadeh B, Wewer UM, Guicheney P, Selenoprotein N. An endoplasmic reticulum glycoprotein with an early developmental expression pattern. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(9):1045–53.

Castets P, Maugenre S, Gartioux C, Rederstorff M, Krol A, Lescure A, Tajbakhsh S, Allamand V, Guicheney P. Selenoprotein N is dynamically expressed during mouse development and detected early in muscle precursors. BMC Dev Biol. 2009;9:46.

Marino M, Stoilova T, Giorgi C, Bachi A, Cattaneo A, Auricchio A, Pinton P, Zito E. SEPN1, an endoplasmic reticulum-localized selenoprotein linked to skeletal muscle pathology, counteracts hyperoxidation by means of redox-regulating SERCA2 pump activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;24(7):1843–55.

Jurynec MJ, Xia R, Mackrill JJ, Gunther D, Crawford T, Flanigan KM, Abramson JJ, Howard MT, Grunwald DJ. Selenoprotein N is required for ryanodine receptor calcium release channel activity in human and zebrafish muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(34):12485–90.

Loscalzo J. Keshan disease, selenium deficiency, and the selenoproteome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1756–60.

Schweizer U, Dehina N, Schomburg L. Disorders of selenium metabolism and selenoprotein function. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23(4):429–35.

Ferreiro A, Quijano-Roy S, Pichereau C, Moghadaszadeh B, Goemans N, Bönnemann C, Jungbluth H, Straub V, Villanova M, Leroy J-P. Mutations of the selenoprotein N gene, which is implicated in rigid spine muscular dystrophy, cause the classical phenotype of multiminicore disease: reassessing the nosology of early-onset myopathies. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(4):739–49.

Moghadaszadeh B, Petit N, Jaillard C, Brockington M, Roy SQ, Merlini L, Romero N, Estournet B, Desguerre I, Chaigne D. Mutations in SEPN1 cause congenital muscular dystrophy with spinal rigidity and restrictive respiratory syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29(1):17–8.

Flanigan KM, Kerr L, Bromberg MB, Leonard C, Tsuruda J, Zhang P, Gonzalez-Gomez I, Cohn R, Campbell KP, Leppert M. Congenital muscular dystrophy with rigid spine syndrome: a clinical, pathological, radiological, and genetic study. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(2):152–61.

Ferreiro A, Ceuterick-de Groote C, Marks JJ, Goemans N, Schreiber G, Hanefeld F, Fardeau M, Martin JJ, Goebel HH, Richard P. Desmin-related myopathy with mallory body–like inclusions is caused by mutations of the selenoprotein N gene. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(5):676–86.

Clarke NF, Kidson W, Quijano-Roy S, Estournet B, Ferreiro A, Guicheney P, Manson JI, Kornberg AJ, Shield LK, North KN. SEPN1: associated with congenital fiber-type disproportion and insulin resistance. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):546–52.

Castets P, Lescure A, Guicheney P, Allamand V. Selenoprotein N in skeletal muscle: from diseases to function. J Mol Med. 2012;90(10):1095–107.

Scoto M, Cirak S, Mein R, Feng L, Manzur A, Robb S, Childs A-M, Quinlivan R, Roper H, Jones D. SEPN1-related myopathies clinical course in a large cohort of patients. Neurology. 2011;76(24):2073–8.

Schweizer U, Fradejas-Villar N. Why 21? The significance of selenoproteins for human health revealed by inborn errors of metabolism. FASEB J. 2016;30(11):3669–81.

Schoenmakers E, Schoenmakers N, Chatterjee K. Mutations in humans that adversely affect the Selenoprotein synthesis pathway. In: Selenium: Springer; 2016. p. 523–38.

Allamand V, Richard P, Lescure A, Ledeuil C, Desjardin D, Petit N, Gartioux C, Ferreiro A, Krol A, Pellegrini N. A single homozygous point mutation in a 3′ untranslated region motif of selenoprotein N mRNA causes SEPN1-related myopathy. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(4):450–4.

Venance S, Koopman W, Miskie B, Hegele R, Hahn A. Rigid spine muscular dystrophy due to SEPN1 mutation presenting as cor pulmonale. Neurology. 2005;64(2):395–6.

D'Amico A, Haliloglu G, Richard P, Talim B, Maugenre S, Ferreiro A, Guicheney P, Menditto I, Benedetti S, Bertini E. Two patients with ‘dropped head syndrome’due to mutations in LMNA or SEPN1 genes. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15(8):521–4.

Ardissone A, Bragato C, Blasevich F, Maccagnano E, Salerno F, Gandioli C, Morandi L, Mora M, Moroni I. SEPN1-related myopathy in three patients: novel mutations and diagnostic clues. Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175(8):1113–8.

Maiti B, Arbogast S, Allamand V, Moyle MW, Anderson CB, Richard P, Guicheney P, Ferreiro A, Flanigan KM, Howard MT. A mutation in the SEPN1 selenocysteine redefinition element (SRE) reduces selenocysteine incorporation and leads to SEPN1-related myopathy. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(3):411–6.

Okamoto Y, Takashima H, Higuchi I, Matsuyama W, Suehara M, Nishihira Y, Hashiguchi A, Hirano R, Ng AR, Nakagawa M. Molecular mechanism of rigid spine with muscular dystrophy type 1 caused by novel mutations of selenoprotein N gene. Neurogenetics. 2006;7(3):175–83.

Tajsharghi H, Darin N, Tulinius M, Oldfors A. Early onset myopathy with a novel mutation in the Selenoprotein N gene (SEPN1). Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15(4):299–302.

Acknowledgements

The authors also gratefully acknowledge the family members for participating in this research study.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the NIMAD research grant (940714) awarded to Mohammad Ali Faghihi. The funding agency has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Availability of data and materials

All data including NGS sequencing raw and analyzed data and Sanger sequencing files will be provided by corresponding author upon request. The identified mutations will be uploaded into ClinVar website.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAF and SAD conceived and designed the study, collected, assembled, interpreted NGS data and were involved in revising the draft critically for important intellectual content. FZ, ES, PH, HN and AS made substantial contribution to the clinical evaluation and acquisition of data, and were involved in revising the draft critically for important intellectual content. HD, MS and MAFF made substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of data, and were involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published and are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethic committee at Persian BayanGene Research and Training Center, Dr. Faghihi’s Medical Genetic Center has approved the study and parents of the affected individual have signed written informed consent indicating their voluntary contribution to the current study. A copy of the consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Consent for publication

Both patient’s legal guardians (parents) have signed informed consent to participate in this study and both families consented to publish result of study, including medical data and images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ziyaee, F., Shorafa, E., Dastsooz, H. et al. A novel mutation in SEPN1 causing rigid spine muscular dystrophy 1: a Case report. BMC Med Genet 20, 13 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-018-0743-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-018-0743-1