Abstract

Background

Advances in the nucleic acid sequencing technologies have ushered in the era of genetic-based “precision medicine”. Applications of the genetic discoveries to practice of medicine, however, are hindered by phenotypic variability of the genetic variants. The report illustrates extreme pleiotropic phenotypes associated with an established causal mutation for hereditary cardiomyopathy.

Case presentation

We report a 61-year old white female who presented with syncope and echocardiographic and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging findings consistent with the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). The electrocardiogram, however, showed a QRS pattern resembling an Epsilon wave, a feature of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). Whole exome sequencing (mean depth of coverage of exons 178X) analysis did not identify a pathogenic variant in the known HCM genes but identified an established causal mutation for ARVC. The mutation involves a canonical splice accepter site (c.2146-1G > C) in the PKP2 gene, which encodes plakophillin 2. Sanger sequencing confirmed the mutation. PKP2 is the most common causal gene for ARVC but has not been implicated in HCM. Findings on echocardiography and CMR during the course of 4-year follow up showed septal hypertrophy and a hyperdynamic left ventricle, consistent with the diagnosis of HCM. However, neither baseline nor follow up echocardiography and CMR studies showed evidence of ARVC. The right ventricle was normal in size, thickness, and function and there was no evidence of fibro-fatty infiltration in the myocardium.

Conclusions

The patient carries an established pathogenic mutation for ARVC and a subtle finding of ARVC but exhibits the classic phenotype of HCM, a contrasting phenotype to ARVC. The case illustrates the need for detailed phenotypic characterization for patients with hereditary cardiomyopathies as well as the challenges physicians face in applying the genetic discoveries in practicing genetic-based “precision medicine”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Backgrounds

Technological advances in nucleic acid sequencing have enabled identification of the genetic variants (GVs) across the genome and have ushered in utilization of the GVs in practice of medicine. Genetic-based “personalized medicine” or “precision medicine” advocates for exploiting the information content of the GVs to determine susceptibility to disease, individualize therapy, in order to maximize gain and to reduce the side effects, prognosticate, and assess the clinical outcomes. In a broader definition, “precision medicine” promotes utilizing various individualized indicators, encompassing metabolomics, transcriptomics, genomics, proteomics, environmental exposures, and microbiome, among others, to tailor the medical management of an individual.

Single gene disorders, whereby the effect size of the GVs are relatively large, are the prototypic diseases for the applications of genetic-based “precision medicine”. However, there is considerable phenotypic variability and pleiotropic effects, even in single gene disorders. The variability typically results from different mutations in a given causal gene causing distinct phenotypes. The point has been illustrated for hereditary cardiomyopathies, whereby different mutations in genes encoding sarcomere proteins can cause either hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) or dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and affect severity of the phenotypic expression [1–3]. However, phenotypic variability of a specific mutation associated with two distinct cardiomyopathy phenotypes is less well appreciated. We report an interesting patient who exhibits the classic phenotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) but carries a rare mutation that has been established to cause the contrasting phenotype of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC).

Case presentation

The patient is a 61-year white (European decent, non-Finish) female who presented with unexplained syncope 4 years ago. She had no prior history of syncope, cardiac arrhythmias, cardiovascular diseases, and no family history of cardiomyopathies. She had a past medical history of depression and mild hypothyroidism, which have been controlled with medical therapy. Her physical examination was unremarkable. A 12-lead ECG was notable for possible left atrial enlargement, q waves in L1 and aVL, a QRS morphology resembling right bundle branch block with an epsilon wave, and non-specific ST and T changes (Fig. 1a and b). Holter monitoring (24 h) showed a run of 5-beat ventricular tachycardia and frequent ventricular premature beats and couplets (Fig. 1c). An echocardiogram showed asymmetric left ventricular hypertrophy with an interventricular septal thickness of 19 mm (normal range: 6–11 mm), a posterior wall thickness of 1.1 cm, a hyperdynamic left ventricle with an ejection fraction of > 60%, a normal right ventricular size and function, and reduced myocardial tissue Doppler velocities (Fig. 1, d–g). She had no overload conditions, such as systemic arterial hypertension or valvular pathology to explain cardiac hypertrophy. The findings were consistent with the diagnosis of HCM. She was treated with a beta-blocker for HCM, which she soon discontinued. She was taking aspirin (81 mg/d), cholecalciferol (1000 units/d), and levothyroxine (75 mg/d), and received monthly intramuscular injection of paliperidone palmitate for depression.

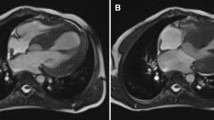

Phenotypic data. a 12-lead electrocardiogram is notable for a QRS morphology resembling right bundle branch block with an epsilon wave, a pattern similar to that observed in Brugada syndrome. b QRS morphology in lead V1 showing an Epsilon wave. c A rhythm strip from a Holter monitoring recording showing a 5-beat non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. d A parasternal long axis echocardiographic view showing interventricular septal hypertrophy. e Septal tissue Doppler imaging, showing reduced velocities. f and g. CMR images, fat saturation sequence f and cardiac function g, showed a normal RV size and function and no gadolinium enhancement in the RV

The proband had no family history of HCM or ARVC (Fig. 2). She was never married and had no child. Proband’s mother (I-2 in the Pedigree) had atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular rate at 80 bpm and left anterior fascicular block on a 12-lead ECG but no Epsilon wave or evidence of cardiac hypertrophy. Individual I-2 had an echocardiogram at 80 years of age, which was 4 years prior to her death, which showed a normal left ventricular size and function with an interventricular wall thickness of 0.9 cm. She had no evidence of right ventricular dilatation or dysfunction on the echocardiogram. Proband’s father (I-1 in the Pedigree) had a history of coronary artery disease and died in a car accident at an old age. Proband’s brother (II-2) had no history of heart disease and died from septic shock and respiratory failure, as complications of liver cirrhosis caused by hepatitis C. Proband’s half-sister had degenerative aortic valve disease and underwent aortic valve replacement in her 50s.

Pedigree. Pedigree of the proband containing the phenotypic data of the key members is shown. Square box and circle represent male and female members respectively. Full circle indicates an affected member. The / symbol indicates a deceased individual. Age at the time of death is shown. Abbreviations: CAD: Coronary artery disease; MVA: Motor vehicle accident; A Fib: Atrial fibrillation; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; HCM: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; AVR: Aortic valve replacement. Age at the time of death is shown in parenthesis are shown in the figure

Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed on the Illumina 2500 platform as part of clinical genetic testing by a commercial company. Sequencing produced 2 × 100 bp reads, which were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19) using BWA-Mem (v0.7.8) [4]. The BAM files, containing the sequence alignment data, were analyzed to identify the GVs using Platypus (v0.8.1) [5]. CASSANDRA (v2.0) was used to annotate the GVs [6]. The discovered variants were filtered by minor allele frequency <1% (ExAc overall minor allele frequency, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/) and prioritized providing they met any of the following criteria:

-

1)

Stop gain, splicing (2 bp of canonical site), and any insertion or deletion

-

2)

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic as annotated by ClinVar [7]

-

3)

Nonsynonymous variants that met all the following criteria

The mean depth of coverage of exons in the entire dataset was 178 times. In the entire data set, 95.3% of the exons had at least 10 sequence reads. Further analysis of the 15 genes known to cause HCM and phenocopy conditions, namely MYBPC3, MYH7, TNNT2, TNNI3, TPM1, ACTC1, MYL2, MYL3, FH11, NEXN, PLN, GLA, LAMP2, and PRKAG2 showed 100% had at least 10 reads and 98% had at least 20 reads (Table 1).

A total of 80 candidate GVs in the WES data, including 29 insertions/deletions, 16 variants a introducing premature stop codon, 3 variants affecting the splicing sites, and 32 deleterious non-synonymous variants met the filtering criteria (Additional file 1: Table S1). No pathogenic variant in any of the established causal genes for HCM was identified. Given the high read coverage (Table 1), the possibility of missing a causal variant in HCM genes was very low. Ten of the candidate pathogenic variants were in genes associated with a phenotype per Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database [10]. The list included CLDN16, COL6A2, COL6A3, FANCD2, GPR179, LFNG, NOTCH3, PKP2, POF1B, TGIF1 (Table 2).

Among the pathogenic variants identified, the most plausible pathogenic variant for the phenotype in the proband is a rare splice variant (c.2146-1G > C) in the PKP2 gene (NM_001005242.2), which encodes plakophilin 2 (<1 in 20,000 in ExAc database in European – Non-Finnish population). PKP2 is the most common causal gene for ARVC [11]. The variant is predicted to disrupt the canonical splice acceptor site in exon 10 of the PKP2 gene and has been reported in multiple independent probands/families to cause ARVC [11–14]. The variant was read 183 times in the WES data and was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 3). Because the c.2146-1G > C variant is known to cause ARVC [11–14], the patient was further evaluated for this distinct form of cardiomyopathy. The ECG and echocardiogram were unchanged. CMR showed interventricular septal hypertrophy but no evidence of right ventricular dilatation, dysfunction, aneurysm, or fibro-adipocyte infiltration (Fig. 1, panels f and g, and Additional file 2: Movie S1 and Additional file 3: Movie S2).

Discussion

Although different mutations in a single gene can cause distinct phenotypes, the observed association of a single mutation with two distinct and contrasting phenotypes, namely HCM and ARVC, is rare, if not unique. The former is characterized by cardiac myocyte hypertrophy, classically in the left ventricle and the latter by myocyte atrophy, apoptosis, and excess fibro-adipocytes, classically in the right ventricle. The patient had a clear clinical diagnosis of HCM, as evidenced by the presence of asymmetric cardiac hypertrophy with a predominant involvement of the interventricular septum, on multiple echocardiograms and CMR, in the absence of a secondary cause, such as systemic arterial hypertension or aortic stenosis. However, the patient did not meet the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of ARVC, despite carrying a well-established mutation in the most common causal gene for ARVC [11]. The QRS pattern resembling an epsilon wave is considered a major, albeit insufficient, diagnostic criterion for the ARVC, evoking possible ARVC [15]. The absence of a full ARVC phenotype in the proband might reflect incomplete penetrance, which is a known feature of the PKP2 variants [14]. The Epsilon wave observed in the proband is not a feature of HCM but is a major diagnostic criterion for ARVC. The electrocardiographic pattern also resembles the pattern observed in Brugada syndrome [16], which is also associated with the PKP2 mutations [17]. However, cardiac hypertrophy is not a feature of the Brugada syndrome.

The published evidence for the pathogenic role of the c.2146-1G > C variant in ARVC is strong [11–13]. However, its causal role in HCM is uncertain. Rare variants, including the pathogenic variants, are population-specific. Consequently, detection of a pathogenic variant, previously identified as a disease-causing variant, in a single individual is insufficient to imply causality. Indeed, unambiguous ascertainment of genetic causality, regardless of the causal gene and variant, is exceedingly challenging if not impossible. HCM in this patient might be caused by undetected pathogenic variants, structural variants, and variants did not meet the filtering criteria [18]. The exome of this patient also contained a rare variant in the OBSCN gene, which is a candidate gene for DCM but not an established causal gene for HCM [19]. As shown in Table 1, WES had provided an excellent coverage to 15 known HCM and HCM-phenocopy genes. Thus, it is very unlikely that a pathogenic variant in the common HCM gene was undetected. Finally, it is also possible that a copy number variant or a large deletion, not detected by whole exome sequencing, is responsible for HCM in this case, albeit such variants are found in < 1% of HCM cases [20]. Thus, one cannot exclude concomitant presence of HCM and ARVC phenotypes in this case.

Conclusions

The case illustrated extreme phenotypic pleiotropy associated with a PKP2 mutation, which is an established causal mutation for ARVC and yet this pathogenic variant was found in a patient with the well-defined contrasting phenotype of HCM. The diversity of the phenotypic expression of GVs does not diminish the clinical utilities of genetic testing in hereditary cardiomyopathies. To the contrary, the findings emphasize the need for better understanding of the phenotypic variability associated with the GVs by placing the focus on detailed phenotypic and genetic characterization of the patient. The ambiguities in genotype-phenotype correlation in this case illustrate the challenges physicians face in applying the genetic discoveries to the practice medicine. To quote Sir William Osler, the practice of “medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability”. It seems to remains so, even in the era of “precision medicine”.

Abbreviations

- ARVC:

-

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy

- CMR:

-

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

- DCM:

-

Dilated cardiomyopathy

- GVs:

-

Genetic variants

- HCM:

-

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- PKP2:

-

Plakophilin 2

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

References

Geisterfer-Lowrance AA, Kass S, Tanigawa G, Vosberg HP, McKenna W, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. A molecular basis for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a beta cardiac myosin heavy chain gene missense mutation. Cell. 1990;62(5):999–1006.

Marian AJ, Mares Jr A, Kelly DP, Yu QT, Abchee AB, Hill R, Roberts R. Sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Variability in phenotypic expression of beta-myosin heavy chain mutations. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(3):368–76.

Kamisago M, Sharma SD, DePalma SR, Solomon S, Sharma P, McDonough B, Smoot L, Mullen MP, Woolf PK, Wigle ED, et al. Mutations in sarcomere protein genes as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(23):1688–96.

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(5):589–95.

Rimmer A, Phan H, Mathieson I, Iqbal Z, Twigg SR, Consortium WGS, Wilkie AO, McVean G, Lunter G. Integrating mapping-, assembly- and haplotype-based approaches for calling variants in clinical sequencing applications. Nat Genet. 2014;46(8):912–8.

Bainbridge MN, Armstrong GN, Gramatges MM, Bertuch AA, Jhangiani SN, Doddapaneni H, Lewis L, Tombrello J, Tsavachidis S, Liu Y, et al. Germline mutations in shelterin complex genes are associated with familial glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(1):384.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/. Accessed 3 Dec 2016.

http://mutationassessor.org/r3/. Accessed 3 Dec 2016.

http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/. Accessed 3 Dec 2016.

https://www.omim.org/. Accessed 3 Dec 2016.

Gerull B, Heuser A, Wichter T, Paul M, Basson CT, McDermott DA, Lerman BB, Markowitz SM, Ellinor PT, MacRae CA, et al. Mutations in the desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 are common in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11):1162–4.

Dalal D, Molin LH, Piccini J, Tichnell C, James C, Bomma C, Prakasa K, Towbin JA, Marcus FI, Spevak PJ, et al. Clinical features of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy associated with mutations in plakophilin-2. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1641–9.

Watkins DA, Hendricks N, Shaboodien G, Mbele M, Parker M, Vezi BZ, Latib A, Chin A, Little F, Badri M, et al. Clinical features, survival experience, and profile of plakophylin-2 gene mutations in participants of the arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy registry of South Africa. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(11 Suppl):S10–7.

Perrin MJ, Angaran P, Laksman Z, Zhang H, Porepa LF, Rutberg J, James C, Krahn AD, Judge DP, Calkins H, et al. Exercise testing in asymptomatic gene carriers exposes a latent electrical substrate of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(19):1772–9.

Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, Calkins H, Corrado D, Cox MG, Daubert JP, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(7):806–14.

Platonov PG, Calkins H, Hauer RN, Corrado D, Svendsen JH, Wichter T, Biernacka EK, Saguner AM, Te Riele AS, Zareba W. High interobserver variability in the assessment of epsilon waves: Implications for diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(1):208–16.

Cerrone M, Lin X, Zhang M, Agullo-Pascual E, Pfenniger A, Chkourko Gusky H, Novelli V, Kim C, Tirasawadichai T, Judge DP, et al. Missense mutations in plakophilin-2 cause sodium current deficit and associate with a Brugada syndrome phenotype. Circulation. 2014;129(10):1092–103.

MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, Rehm HL, Shendure J, Abecasis GR, Adams DR, Altman RB, Antonarakis SE, Ashley EA, et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature. 2014;508(7497):469–76.

Marston S, Montgiraud C, Munster AB, Copeland O, Choi O, Dos Remedios C, Messer AE, Ehler E, Knoll R. OBSCN mutations associated with dilated cardiomyopathy and haploinsufficiency. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138568.

Lopes LR, Murphy C, Syrris P, Dalageorgou C, McKenna WJ, Elliott PM, Plagnol V. Use of high-throughput targeted exome-sequencing to screen for copy number variation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58(11):611–6.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from NIH, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI, R01 HL088498, 1R01HL132401, and R34 HL105563), Leducq Foundation (14 CVD 03), Roderick MacDonald Foundation (13RDM005), TexGen Fund from Greater Houston Community Foundation, Texas Heart Institute Foundation, and George and Mary Josephine Hamman Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

All data, without identifiers, will be made available per request. The contact person is A.J. Marian, M.D., email: Ali.J.Marian@uth.tmc.edu.

Authors’ contributions

MB and LL analyzed whole exome data, YT collected the clinical data, BC performed and analyzed cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and AJM supervised all components of the study, analyzed the phenotype data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Consent was obtained from the proband and her half-sister about publication of clinical and genetic information. The proband also provided consent for publication of data on her family history (members are deceased individuals).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

List of candidate pathogenic variants in proband’s exome met the filtering criteria; Description: 80 pathogenic variants are listed. (PDF 75 kb)

Cine CMR 1; Description: CMR showing normal RV and LV function and no RV dilatation. (MOV 1995 kb)

Cine CMR 2; Description: CMR showing normal RV and LV size and no RV wall thinning or aneurysm. (MOV 2605 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bainbridge, M.N., Li, L., Tan, Y. et al. Identification of established arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy mutation in a patient with the contrasting phenotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. BMC Med Genet 18, 24 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-017-0385-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-017-0385-8