Abstract

Background

Sexually transmitted infections continue to be a significant public health issue on a global scale. Due to their effects on reproductive and child health as well as their role in facilitating the spread of HIV infection, sexually transmitted infections impose a heavy burden of morbidity and mortality in many developing countries. In addition, stigma, infertility, cancer, and an increased risk of HIV are the primary impacts of STIs on sexual and reproductive health. While numerous studies have been conducted in Tanzania to address this specific topic in various settings, the majority of them weren’t representative. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to use data from the most recent Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey in order to evaluate the individual and community-level factors associated with sexually transmitted infections among Tanzanian men at the national level.

Methods

The most recent datasets from the Tanzania demographic and health survey were used for secondary data analysis. A total of 5763 men participated in this study. The recent Tanzania demographic and health survey provides data for multilevel mixed effect analysis on the variables that contribute to sexually transmitted infections among men in Tanzania. Finally, the percentage and odd ratio were provided, together with their 95% confidence intervals.

Result

This study includes a total weighted sample of 5763 men from the Tanzania demographic and health survey. Of the total study participants, 7.5% of men had sexually transmitted infections in the last twelve months. Being married [AOR: 0.531, 95% CI (0.9014, 3.429)] was a factor that reduced the risk of sexually transmitted infections among men. On the other hand, being between the age range of 20 and 24 years [AOR: 6.310, 95% CI (3.514, 11.329)] and having more than one union [AOR: 1.861, 95% CI (1.406, 2.463)] were the factors that increased the risk of sexually transmitted infections among men.

Conclusions

Men’s sexually transmitted infections have been associated with individual-level factors. So, the Tanzanian governments and the concerned stakeholders should provide special attention for men whose age range is 20–24 years old. Promoting marriages and limiting the number of sexual partners should be the main strategies to lower the risk of sexually transmitted infections among men in Tanzania.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a group of infections that are predominantly transmitted through unprotected sexual contact (vaginal, anal, and oral sex) with an infected person [1] and Some STIs can also be transmitted through skin-to-skin contact, from mother-to-child during pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding [2]. Due to the impact that sexually transmitted infections have on reproductive and child health, as well as their role in promoting HIV infection, sexually transmitted infections impose a heavy burden of morbidity and mortality in many developing nations [3]. Globally, sexually transmitted infections other than HIV remain a major public health problem. Despite the strong association between STIs and HIV acquisition, STIs other than HIV have been overshadowed in recent years by the heightened public-health focus on HIV treatment. Naturally, STIs affect individuals who are part of partnerships and larger sexual networks, and in turn, the general population [4, 5].

In 2020, there were an estimated 374 million new infections of four curable sexually transmitted infections among people aged 15–49 years worldwide; about 26% (96 million) of these occurred in Africa [6]. Globally, common types of STIs in men include chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and genital herpes [7]. Some of the most common STIs in men may not produce signs or symptoms [8]. These infections can have a serious impact on health status including pelvic inflammatory disease, stigmatization, infertility, cancers, increase the risk of HIV, adverse mental health, congenital deformities [6, 9, 10], and drug resistance is a major threat to reducing the burden of STIs worldwide [11]. There were an estimated 376 million new curable STIs annually. Additionally, more than 500 million people have genital infections with the herpes simplex virus, which predominantly occur in developing countries [10].

The government of the United Republic of Tanzania has endorsed several global commitments and their respective plans of action to improve quality of life and achieve the elimination of new HIV infections [12]. Additionally, in Tanzania, the national policy calls for recommending HIV testing to every person who comes to a health facility, regardless of their malady [13]. But little attention was given to other STIs due to the heightened public-health focus on HIV prevention and treatment in recent years compared to STIs. Although there are several studies that were done in Tanzania to address this particular topic in different settings, study periods, and sample sizes [14,15,16,17]. But most of them lack representativeness. So, the major objective of this study was to evaluate individual and community-level factors associated with sexually transmitted infections among men in Tanzania at the national level by using the recent Tanzania demographic and health survey. Since policymakers prefer country-level data and findings for designing and executing appropriate intervention programs at different levels to reduce sexually transmitted infections, the findings of this study would provide better evidence for policymakers and other stakeholders.

Methods and material

Study setting and period

Tanzania is an East African country situated just south of the Equator. The Tanzania mainland is bounded by Uganda, Lake Victoria, and Kenya to the north; by the Indian Ocean to the east; by Mozambique, Lake Nyasa, Malawi, and Zambia to the south and southwest; and by Lake Tanganyika, Burundi, and Rwanda to the west [18]. The Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey was implemented by the Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and the Office of Chief Government Statistician (OCGS) in collaboration with the Ministries of Health of Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar and other stakeholders. The 2022 TDHS is the 7th Demographic and Health Survey conducted in Tanzania since 1991–92. Data collection took place from February to July 2022 in Tanzania, the Mainland and Zanzibar [19].

Data source / data extraction

After permission was secured through an online request by explaining the aim of the study, the data for this analysis was obtained from the 2022 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey, which can be accessed at the DHS portal (https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin/index.cfm.

Study design and sampling procedures

A community-based cross-sectional study design was employed. The sample design for the 2022 TDHS was carried out in two stages and was intended to provide estimates for the entire country, for urban and rural areas in Tanzania Mainland, and for Zanzibar. The first stage involved the selection of sampling points (clusters) consisting of enumeration areas (EAs) delineated for the 2012 Tanzania Population and Housing Census (2012 PHC). The EAs were selected with a probability proportional to their size within each sampling stratum. A total of 629 clusters were selected. Among the 629 EAs, 211 were from urban areas and 418 were from rural areas. In the second stage, 26 households were selected systematically from each cluster, for a total anticipated sample size of 16,354 households for the 2022 TDHS. In a subsample of half of all households selected for the survey, all men ages 15–49 were eligible to be interviewed if they were either usual residents or visitors in the household on the night before the survey interview. In the subsample (50% of households) of households selected for the male questionnaire, 6,367 men ages 15–49 were identified as eligible for individual interviews, and 5,763 were successfully interviewed, yielding a response rate of 91% [19]. The final variable for this study was sexually transmitted infection among men. This study employed a total of 5,763 samples(Fig. 1).

Showed that the diagrammatically presentation of the sampling procedures of men participants in Tanzania demographic survey 2022 [19]

Study variables

The outcome variable

for this study was sexually transmitted infection. If the men hadn’t had any sexually transmitted infections in the last 12 months, which were labeled “no” and coded as “0,” that means the respondent hadn’t had STIs in the last 12 months, and if the men had sexually transmitted infections in the last 12 months, which were labeled “yes” and coded as “1,” that means the respondent had a history of STIs in the last 12 months.

Individual level variables

Age groups, educational status, marital status, sex of household head, wealth index, respondent circumcised, number of unions, reading newspapers, listening to radio, watching television, using the internet, using health insurance, currently working, and information about STI.

Community level variables

place of residence.

Data management and analysis

To accommodate the intricate survey design, we took weighting, stratification, and clustering into consideration throughout the entire analysis process. To arrive at this result, the standard weights of the men and the total number of men in the country were divided by the corresponding survey sampling proportion. Data extraction, recoding, descriptive analysis, and analytical analysis were performed using STATA version 14.

Due to the hierarchical structure of the demographic and health survey data, a multilevel mixed effect model analysis was employed. The variation was assessed using the Interclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was used to evaluate model fitness and model comparison. Four models were built for this multistage investigation. The first model was built without independent factors; it is possible to determine the extent of cluster variation in the STI among men. The second model was fitted with individual-level factors alone. Community-level characteristics were incorporated into the third model. Finally, the fourth model took into account factors at both the individual and community levels. The model with the lowest deviance (AIC) value provided the best-fitting model. Then, bivariate analysis was employed in order to select the factors for multivariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, variables with p < 0.05 significance levels were considered to be significant predictors of STI among men. Finally, the percentage and odd ratio were provided, together with their 95% confidence intervals.

Ethical consideration

For this particular investigation, an ethical review and participant agreement were not required because the demographic and health survey program utilized secondary, easily accessible survey data. We requested permission from the DHS Program to use the data we obtained from their website, and they gave it to us.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

In all, 5763 men participated in this investigation. There were about 1444 people (25.1%) in the 15–19 age range. 3825 (66.4%) of the respondents were rural residents; 3134 (54.4%) attended primary school; 2621 (45.5%) were married; 4807 (83.4%) were households headed by men; and 3110 (54.0%) were poor in wealth; 2314 (40.2%) read magazines; 4570 (79.3%) listened to the radio; 4437 (77.0%) watched television; 1416 (24.6%) used the internet; 389 (6.8%) had health insurance, and 4951 (85.9%) had undergone circumcision. 699 (12.1%) had multiple unions; 1517 (26.3%) had recently engaged in sexual activity; and 4689 (81.4%) were employed. 4555 (79.05%) had information about STIs, and 430 (7.5%) had experienced a STI in the last 12 months (Table 1).

Model comparison

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in the null model showed that among men, there was a variation in sexually transmitted infections of 14.02% accounted for by inter-cluster differences. The variance in sexually transmitted infections among men is described by variables at the individual level in 13.97% of differences. The difference in sexually transmitted infections among men is accounted for by community-level variables at 9.83%. In the end, 7.87% of the variations among men were caused by variables at the individual and community levels. As a result, it was determined that Model IV, which included factors at both the individual and community levels, had the lowest deviance (AIC) value. Therefore, Model IV is the best-fitted model, and every interpretation and report were made based on this model (Table 2) .

Factors analysis associated with sexually transmitted infections

The results of the bivariable analysis using model IV showed that among men, sexually transmitted infections were statistically and significantly associated with age groups, marital status, wealth index, reading newspapers, listening to radio, watching television, using the internet, number of unions, and currently working. The results of the multivariate analysis demonstrated that sexually transmitted infections were statistically and significantly associated with age groups, marital status, listening to radio, and the number of unions.

The finding from this study shows that the odds of sexually transmitted infections between the age range of 20 and 24 years old were 6.310 times more likely [AOR: 6.310, 95% CI (3.514, 11.329)] compared to men whose ages were between 15 and 19-years old’s. The odds of sexually transmitted infections among men who were married were 0.531 times less likely [AOR: 0.531, 95% CI (0.9014,3.429)] relative to men who were not married. The odds of sexually transmitted infections among men who were listening to radio were 1.400 times more likely [AOR: 1.400, 95% CI (1.012, 1.937)] compared to their counterparts. The odds of sexually transmitted infections among men who had more than one union were 1.861 times more likely [AOR: 1.861, 95% CI (1.406,2.463)] compared to men who had only one union (Table 3).

Discussions

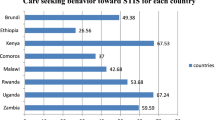

The prevalence’s of sexually transmitted infections among men in united republic of Tanzania were 7.5%. This finding was in line with study which were conducted in Ghana(6%) [20], Kenya 7.4% [21], in Africa (7.7%) [22]. This finding was lower than the study which conducted in Liberia (13.4%) [23]. This finding was higher than the study which was conducted in Guinea (5.9%) [24]. The first possible reasons for this variation were a difference in the study period, method of estimation, sample size, socioeconomic status, and the geographic location of the study area, which could be the cause of the discrepancy between our findings and those of the previously mentioned studies. The second possible reason for this variation were socio-cultural practices and beliefs that affected health-seeking behaviors towards STIs. Additionally, STI patients still resort to the use of traditional methods in treating their infections due to their traditional ethno-medical beliefs.

The finding from this study shows that the odd of sexually transmitted infections between the age range of 20–24 years old were more likely compared to men whose ages were between 15 and 19 years old’s. This finding was supported by the study which was conducted in Ghana [20] and Ethiopia [25]. Adolescents and young adults are particularly vulnerable to sexually transmitted infections [26]. But in cases of our finding, adolescents, particularly those between the ages of 20 and 24, were more likely compared to men whose ages were between 15 and 19 years old. This might be in the age groups of 20–24 years; most of the young men have become independent or started living independently compared to the young men between the ages of 15 and 19 years old. This makes them more susceptible to having multiple sexual partners, peer pressure, difficulty accessing health services, feeling uncomfortable discussing their sexual lives with a doctor, and lacking insurance, which can make it more challenging for young men (20–24 years old) to get sexually transmitted infection testing and treatments compared to young men between the ages of 15 and 19 years old. On the other hand, most of the time, young men who were found between the ages of 15 and 19 were living with their parents. As a result, they became less prone to risky sexual behaviors, peer pressure, and their health insurance was covered by their parents.

The odd of sexually transmitted infections among men who were married were less likely relative to men who were others (living with partner, widowed, divorced, and no longer living together). This finding was supported by the study which was conducted in Ethiopia [27, 28], and in united states [29]. A potential explanation is that societal norms and expectations related to marriage, which value fidelity and monogamy, are frequently linked to marriage. These social norms have the potential to discourage men from engaging in risky behavior by discouraging extramarital affairs. This could be more explained by the fact that in Tanzania, religious people play spiritual and advisory roles in the sexual activities of adolescents. The standing norm drawn from religious and social beliefs is “no sex before marriage [30]. Those norms discourage men from engaging in risky sexual behaviors before marriage, which results in a low incidence of STIs among married men. Moreover, marriage can foster emotional closeness and fulfillment, which lessens the perception of the need to pursue satisfaction through risky extramarital sex [31, 32]. Additionally, being married predisposes one to take preventive measures against the spread of sexually transmitted infections. In contrast to this, never-married youths are repeatedly exposed to unprotected sex at a young age, which increases the risk of contracting STIs [33].

The odd of sexually transmitted infections among men who were listening to radio were more likely compared to their counterparts. This could be explained from the perspective that often these media platforms show health promotional messages that encourage people to go for testing, and by so doing, many men become aware of their STI status [34,35,36]. So. The reporting and testing rate of STIs became high among men who were exposed to those media. Another reason for this finding could be that some media carry sexually explicit content that could entice adolescent men to engage in risky sexual behaviors, which increases their chances of reporting STIs [23, 37, 38]. This finding was contradicted by the studies which were conducted in Ethiopia [39], and in Ghana [20]. The possible reason might be the media is broadcasting STI prevention information. The information may have enabled men to avoid unsafe sexual practices to protect themselves from STIs and HIV/AIDS [40, 41].

Men who were in multiple relationships had a higher probability of contracting sexually transmitted infections than men who were in just one relationship. This finding was supported by the studies which were conducted in Kenya [39, 42]in south Africa [26], in Ethiopia [43] and Britain [44]. It is well established that having multiple sexual partners increases the risk of acquiring STIs. Because of this, the two recommended methods to prevent STIs are abstinence and becoming faithful to one sexual partner [45, 46].

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study had many strengths, for instance; the DHS has a similar design with identical variables in a different environment; the result may, therefore, be applicable to other similar locations. The study used a sufficiently large sample size at the national level to ensure its representativeness. Yet, we would like to assure our reader that a few limitations need to be taken into account. Recall bias is one of the potential drawbacks, especially for retrospective data based on past experiences. Additionally, the magnitude of the bias is often unknown, and correcting for the bias is difficult. Furthermore, this study was a cross-sectional study. It doesn’t show temporal relationships between independent and dependent variables, which may affect the deterrent factors of sexually transmitted infections among men. The final potential limitation of this study was the use of a community-based design that depends on their history of STI in the last 12 months and didn’t implement the laboratory diagnosis on the spot of data collection.

Conclusion and recommendation’s

Men’s sexually transmitted infections have been associated with individual-level factors. So, the Tanzanian governments and the concerned stakeholders should provide special attention for men whose age range is 20–24 years old. Promoting marriages and limiting the number of sexual partners should be the main strategies to lower the risk of sexually transmitted infections among men in Tanzania.

Data availability

The data were obtained from the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2022, which was found at the DHS portal (https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin/index.cfm).

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). 2023.

Hazra A, Collison MW, Davis AM. CDC sexually transmitted infections Treatment guidelines, 2021. JAMA. 2022;327:870–1.

Aral SO, Over M, Manhart L, Holmes KK. Chapter 17. Sexually Transmitted Infections. Dis Control Priorities Dev Ctries (2nd Ed. 2006;311–30.

Low N, Broutet N, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Barton P, Hossain M, Hawkes S. Global control of sexually transmitted infections. Lancet (London England). 2006;368(9551):2001–16.

Peredo C. Sexually transmitted infections (sti) in Chile. Rev Med Clin Las Condes. 2021;32(5):611–6.

World Health Organization (WHO). Prevention and Treatment of HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections for Sex Workers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. 2012;(December):52. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77745/1/9789241504744_eng.pdf

Michael Ray Garcia, Stephen W. Leslie; Anton A. Wray. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2023.

Richens J. Main presentations of sexually transmitted infections in men. BMJ. 2004;328(7450):1251–3.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. WHO Guidel [Internet]. 2014;(July):184. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128048/1/9789241507431_eng.pdf?ua=1

Voth ML, Akbari RP. Sexually transmitted proctitides. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007;20(1):58–63.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030. 2022.

Ministry Of Health. Community Development, Gender E and C. Tanzania-KP-GUIDELINE-1.pdf. 2017.

Mmbaga EJ, Leyna GH, Leshabari MT, Tersbøl B, Lange T, Makyao N, et al. Effectiveness of health care workers and peer engagement in promoting access to health services among population at higher risk for HIV in Tanzania (KPHEALTH): study protocol for a quasi experimental trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):801.

Aboud S, Buhalata SN, Onduru OG, Chiduo MG, Kwesigabo GP, Mshana SE et al. High prevalence of sexually transmitted and Reproductive Tract Infections (STI/RTIs) among patients attending STI/Outpatient Department clinics in Tanzania. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2023;8(1).

Abdul R, Gerritsen AAM, Mwangome M, Geubbels E. Prevalence of self-reported symptoms of sexually transmitted infections, knowledge and sexual behaviour among youth in semi-rural Tanzania in the period of adolescent friendly health services strategy implementation. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018;18(1):229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3138-1

Cheng Y, Paintsil E, Ghebremichael M. Syndromic versus Laboratory Diagnosis of Sexually Transmitted Infections in Men in Moshi District of Tanzania. AIDS Res Treat. 2020;2020.

UNAIDS, UNICEF, WHO. United republic of Tanzania UNAIDS/WHO Epidemiological Fact Sheet on HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infections – 2004 Update. 2005.

Ingham K, Chiteji,. Frank Matthew M. Adolfo C. and Bryceson. Deborah Fahy. Tanzania. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Tanzania. 2024.

Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey. 2022.

Seidu AA, Agbaglo E, Dadzie LK, Tetteh JK, Ahinkorah BO. Self-reported sexually transmitted infections among sexually active men in Ghana. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021;21(1):993. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11030-1

Oluoch T, Mohammed I, Bunnell R, Kaiser R, Kim AA, Gichangi A, et al. Correlates of HIV infection among sexually active adults in Kenya: A National Population-based survey. Open AIDS J. 2012;5(1):125–34.

Semwogerere M, Dear N, Tunnage J, Reed D, Kibuuka H, Kiweewa F et al. Factors associated with sexually transmitted infections among care-seeking adults in the African Cohort Study. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021;21(1):738. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10762-4

Seidu AA, Ahinkorah BO, Dadzie LK, Tetteh JK, Agbaglo E, Okyere J et al. A multi-country cross-sectional study of self-reported sexually transmitted infections among sexually active men in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020;20(1):1884. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09996-5

Tetteh JK, Aboagye RG, Adu-Gyamfi AB, Appiah SCY, Seidu AA, Attila FL, et al. Self-reported sexually transmitted infections among men and women in Papua New Guinea: a cross-sectional study. Heal Sci Rep. 2024;7(3):e1970.

Tamrat R, Kasa T, Sahilemariam Z, Gashaw M. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Sexually Transmitted Infections among Jimma University Students, Southwest Ethiopia. Khamesipour F, editor. Int J Microbiol [Internet]. 2020;2020:8859468. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8859468

Francis SC, Mthiyane TN, Baisley K, Mchunu SL, Ferguson JB, Smit T, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among young people in South Africa: a nested survey in a health and demographic surveillance site. PLoS Med. 2018;15(2):e1002512.

Asresie MB, Worede DT. Factors Associated with risky sexual Behavior among Reproductive-Age men in Ethiopia: evidence from Ethiopian Demography and Health Survey 2016. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2023;15:549–57.

Hong R, Mishra V, Govindasamy P. Factors associated with prevalent HIV infections among Ethiopian adults: Further analysis of the 2005 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. DHS Furth Anal Reports No 57 [Internet]. 2008; http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FA57/FA57.pdf

Kposowa AJ. Marital status and HIV/AIDS mortality: evidence from the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Int J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013;17(10):e868–74. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971213001094

Kamanzi A, Shilunga A. The role of the Church in the Transformation of ‘No sex before marriage’ Social Norm in Tanzania: from shameful to responsible sex. East Afr J Tradit Cult Relig. 2021;4(1):61–8.

Commission NP. Nigeria demographic and health survey 2013. National Population Commission, ICF International; 2013.

Seidu AA, Darteh EKM, Kumi-Kyereme A, Dickson KS, Ahinkorah BO. Paid sex among men in sub-saharan Africa: analysis of the demographic and health survey. SSM-Population Heal. 2020;11:100459.

Yi S, Tuot S, Yung K, Kim S, Chhea C, Saphonn V. Factors associated with risky sexual behavior among unmarried most-at-risk young people in Cambodia. 2014.

Westoff CF, Koffman DA, Moreau C. The impact of television and radio on reproductive behavior and on HIV/AIDS knowledge and behavior. DHS Anal Stud [Internet]. 2011;(24):xi-pp. http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/AS24/AS24.pdf

Hossain M, Mani KKC, Sidik SM, Shahar HK, Islam R. Knowledge and awareness about STDs among women in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2014;14(1):775. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-775

Adegboye OA, Ezechukwu HC, Woodall H, Brough M, Robertson-Smith J, Paba R et al. Media exposure, behavioural risk factors and HIV Testing among women of Reproductive Age in Papua New Guinea: a cross-sectional study. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(2).

Gruber E, Grube JW. Adolescent sexuality and the media: a review of current knowledge and implications. West J Med. 2000;172(3):210–4.

Lin WH, Liu CH, Yi CC. Exposure to sexually explicit media in early adolescence is related to risky sexual behavior in emerging adulthood. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0230242.

Dagnew GW, Asresie MB, Fekadu GA. Factors associated with sexually transmitted infections among sexually active men in Ethiopia. Further analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232793.

Coyle K, Basen-Engquist K, Kirby D, Parcel G, Banspach S, Collins J et al. Safer choices: reducing teen pregnancy, HIV, and STDs. Public Health Rep. 2016.

Country health ranking and roadmaps. Mass media and social marketing campaigns to prevent HIV and other STIs. 2024.

Winston SE, Chirchir AK, Muthoni LN, Ayuku D, Koech J, Nyandiko W, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections including HIV in street-connected adolescents in western Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91(5):353–9.

Mengistu TS, Melku AT, Bedada ND, Eticha BT. Risks for STIs/HIV infection among Madawalabu University students, Southeast Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1):1–7.

Fenton KA, Mercer CH, Johnson AM, Byron CL, McManus S, Erens B, et al. Reported sexually transmitted disease clinic attendance and sexually transmitted infections in Britain: prevalence, risk factors, and proportionate population burden. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Supplement1):S127–38.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006–2015 : breaking the chain of transmission. 2022.

Organization WH. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs): the importance of a renewed commitment to STI prevention and control in achieving global sexual and reproductive health. World Health Organization; 2013.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Measure DHS for their permission to access the Tanzania demographic and health survey 2022 datasets.

Funding

For this study, the author did not receive any financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M., S.M., E.M.A., A.B.K., G.B., M.B. A.A., A.G. and B.K. were worked on this study from start to finish, including design, data extraction, data cleaning and coding, data analysis and interpretation, and composing and revising the manuscript. G.M. then completed the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical clearance and consent to participate

No applicable.

Consent for publication

No applicable.

Competing interests

In relation to the research, authorship, and publication of this work, the authors (G.M.), (S.M.), (E.M.A.), (A.B.K.), (G.B.), (M.B.) (A.A.) (A.G.) and (B.K.), disclosed no possible conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mankelkl, G., Abdu, S.M., Asefa, E.M. et al. Individual and community level factors associated with sexually transmitted infections among men in Tanzania: insights from the Tanzania demographic and health survey of 2022. BMC Infect Dis 24, 580 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09470-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09470-2