Abstract

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) treatment delay is one of the major challenges of TB care in many low-income countries. Such cases may contribute to an increased TB transmission and severity of illness. The aim of this study was to determine the magnitude of patient delay in TB treatment, and associated factors in Dale District and Yirgalem Town administration of Sidama Region, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods

Between January 1-Augst 30/ 2022, we studied randomly selected 393 pulmonary TB cases on Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS) in Dale District and Yirgalem Town Administration. After conducting a pretest, we interviewed participants on sociodemographic, health seeking behavior and clinical factors and reviewed the TB registry. Trained enumerators interviewed to collect data. We entered data in to EPI-info 7 version 3.5.4 and then exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23 for analysis. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify associated factors of TB and statistical significance was defined using the 95% confidence interval.

Result

A total of 393 (98%) participants involved in the study. The magnitude of delay in TB treatment among the study participants was 223 (56.7%) (95% CI (51.8 – 61.6%)). Distance of the health facility from home, (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.04, 95% CI (1.3, 3.2)), seeking antibiotic treatment before being diagnosed for TB (AOR = 2.1, 95% CI (1.3, 3.5)) and the knowledge of TB prevention and treatments (AOR = 5.9, 95% CI (3.6, 9.8)), were factors associated with delay in TB treatment.

Conclusion

The prevalence of TB treatment delay among pulmonary TB patients in the study setting was high. Delay in TB treatment was associated with knowledge, behavioral and accessibility related factors. Providing health education and active case finding of TB would help in minimizing the delay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the Global tuberculosis (TB) report 2022, an estimated 9.9 million people were diseased with TB in 2020 [1]. Ethiopia is one of the 30 high TB burden countries. A recent report from the country showed that more than half of TB patients faced having delay in treatment-seeking [2]. Delay in seeking treatment among TB patients is one of the major challenges of TB care in most low-income countries like Ethiopia [3]. Such cases may be contributing to an increased TB transmission and severity of illness.

Delay in TB treatment could be due to patient delay which consists of the time elapsed between onset of TB symptoms and first self-presentation to formal health care or provider delay which comprises of the time elapsed between first presentation to formal care and anti-TB treatment initiation. Identifying the magnitude and factors associated with patient delay in treatment-seeking will help to improve TB control by improving case findings, providing early treatment, and reducing infection sources in the community [2, 4].

The magnitude of patient delay in TB treatment was 69% in South India in 2014 [5], 72% with greater than 30 days delay in Colombia in 2014 [6], 34.8% with a median delay of 32 days in Turkey in 2019 [7], 65.5% in Iran in 2018 [8], and 61 and 30 days in Peruvian Amazon in 2012 and Thailand in 2008 [9, 10], respectively. African studies reported prevalence of 61% in Nigeria in 2012 [11] and 48% in Zimbabwe in 2014 [12]. A cross-sectional study in Bamako, Mali reported the median patient delay of TB treatment was 58 days [13]. Over half (56.3%) of all involved patients delay in seeking health care for more than 30 days after the onset of their TB symptoms [14]. In a cross-sectional study most (57.8%) of the TB diagnosis delayed for over 21 day [15].

Reports from Ethiopia showed that TB treatment delay was 62.3% in the North Wollo Zone in 2015 [16], 42% in Addis Ababa in 2016 [17], 50.9% in Gedeo Zone in 2020 and 56.9% Gamo Zone in 2017 [18, 19]. The pooled prevalence of TB treatment seeking delay was 44.29% in Ethiopia [20]. The median patient delay in TB diagnosis in Hadiya Zone, South Ethiopia was 30 days [21]. A meta-analysis paper showed that the median time of patient delay was 24.6 days [22]. A recent report also confirmed that the median patient delay was higher among pastoralists (35.5 days) than among non-pastoralists [23].

Concerning factors associated with patient delay in TB treatment, low income, rural residency, unemployment, old age, and female sex, distance to the DOTs centers, low education level, social reasons and non-request of health workers were the associated factors of patient delay in TB treatment [13, 24, 25]. Factors like lack of knowledge, fear and embarrassment of receiving TB diagnosis, patient tendency to get self-treatment before seeking formal medical care, use of dispensary and private health facilities, employed individuals, secondary-level education and tertiary education, body mass index (BMI) status were also reported as risk factors of patient related TB treatment delay in other settings [15, 18, 26]. The overall TB knowledge was not statistically associated with seeking health care for TB diagnosis [14], while other treatment seeking before formal health care provider, residence of the patient, the type of TB, educational level, distance from the DOTS center, lack of awareness about TB, consulting non-formal health provider, and being rural resident were associated factors of treatment delay reported by other studies [20, 22]. Socioeconomic and perception related factors, urban residence, religious views, low income, misconception about the time of TB treatment to be cured and lack of comfort with DOTS were associated with patient delay in TB diagnosis [21].

There is a recent report that estimated the magnitude of TB treatment delay among TB patients on DOTS in Hawassa City Health Centers in Sidama Region [27]. These cases consisted of TB cases mainly coming from urban areas. However, there is no report from the current study area, Yirgalem town and Dale District in the Sidama Region, which consists of both urban and rural population, and where the incidence and prevalence of TB are high. Bacteriological confirmed TB case notification rate in Sidama Region was 163 per 105populations in 2022 [28]. Dale district and Yirgalem town are among the districts with the highest burden. The aim of this study was to determine the magnitude of patient delay in TB treatment, and associated factors in Dale District and Yirgalem Town administration of Sidama Region, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study design, setting and period

The study design used in the current study was a facility-based cross-sectional study conducted during the period from January 1 to Augst 30/2022 in Dale District and Yirgalem Town Administration of the Sidama region, South Ethiopia. Sidama Region constitutes over four million people. The administrative town of Dale district; Yirgalem is located at about 47 km away from Hawassa, the Region capital and at 321 km to the south of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Dale district consists mainly rural population which has a total population of 254,652 residing in 34 kebeles (smallest administrative unit). Regarding the health care facility, the district has one General Hospital, twelve health centers, 34 health posts, and 2 private clinics, and 3 drug vendors. At the time we collected data, all government health facilities in the district are providing DOTs by trained health workers. All pulmonary TB patients on DOTs during the study period, and registered at public health facilities in the districts were considered as our source population. Randomly selected pulmonary adult TB cases at least fifteen years of age were considered as the study population. Pulmonary TB cases who were critically ill, and not volunteer to be interviewed due to their illness were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling procedures

Sample size was calculated by using single population proportion formula. A proportion of 50.9% delay in TB treatment in Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia was considered [19]. Using a 95% confidence interval (CI), 5% of marginal error and 5% non-response rate, the minimum sample size estimated for the study was 403 TB cases. We included Yirgalem General Hospital and all of the 12 health centers to recruit the study participants. Proportional allocation of TB cases was done according to the number of TB cases in each of the health facilities. Figure 1 shows schematic presentation of the sampling procedure. Patients who were on follow up during the data collection period were listed by using the patients’ medical registration number and then participants were selected using simple random sampling method from the list. Then when patients came to the facilities to receive their TB care they were interviewed. Data were collected until the required sample size was achieved.

Variables of the study

The dependent variables considered in the study was patient delay in TB treatment. Independent variables were socio-demographic characteristics such as age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, religion, occupation, residence area, educational level, family size and family monthly income. Health seeking behavior of patients, clinical characteristics and knowledge on TB treatment were other independent variables considered in the study.

Data collection tools and procedure

We mainly used a pre-tested and interviewer-administered questionnaire to collect the data. Data on smear positivity and X-rays were obtained by record review. The instrument was developed after reviewing of previous studies [16,17,18,19]. We asked participants socio-demographic characteristics related variables. Questions about clinical factors, visiting other health facilities and knowledge on TB treatments were also included in the questionnaire. Supplementary material (S1) shows the tool we used for knowledge related factors assessment.

The questionnaire was first prepared in English and then it was translated in to the local language (Sidamu afoo) and then it was back translated in to English to check the consistencies in meaning. The Sidamu afoo version questionnaire was used for the data collection purpose. Thirteen health professionals with a B.Sc. degree in nursing or public health working in the facilities and 2 supervisors with MPH training working in the district offices, were assigned to collect the data. The data collectors were fluent speakers of both Amharic and Sidamu Afo.

Data quality control

Data collectors and supervisors were trained on issues related to the research aim, data collection methods, and data collection tool. The collected data were reviewed on daily basis. Data completeness and missing value were checked before analysis. The questionnaire was pretested on 5% of sample size in the neighboring Wonsho District, which was not included in the study. Based on the pre-test finding, logical sequence, clarity of the questionnaire and the questions that had made confusion for the respondents were revised. An updated questionnaire was used to collect the final data. During the data collection process, any problem encountered was discussed with the team and were solved immediately.

Operational definitions

Pulmonary TB cases

Refers to patients with two or more sputum smears or gene x-pert positive for acid-fast bacilli were considered as smear-positive pulmonary TB cases. Cases diagnosis by clinical and x-ray evidences (smear negative by Zehil Nelson Staining or gene x-pert) were considered as smear-negative pulmonary TB cases [29].

Patient delay

Refers to the time interval between onset of symptoms mainly having of cough for over 2–3 weeks and the patient’s first contact with a healthcare provider. If TB cases are presented to modern health facility thirty days after initial start of the TB symptom considered as delayed [30, 31].

Knowledge

Patients who scored more than the set average (50%) were considered knowledgeable and those who scored less than average were considered as low knowledgeable [19].Variables measuring knowledge were recorded on a 3-point Likert scale of 10 questions. These include by asking questions on the knowledge about the type of disease, its causes, curability, and type of anti TB drugs, and the duration of treatment. Knowledge related factors assessment tool is submitted as a supplementary material (supplementary material 1).

Data analysis procedure

Data were coded and entered in to EPI-info 7 version 3.5.4 statistical software and then exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23. Data were cleaned. The data were presented by using tables. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis were used to show relationship between variables. Independent variables with a p-value less than or equal to 0.25 in the bi-variable were entered in to multivariable logistic regression model to control the effects of confounders. The presence of association between predictor variables and delay in TB treatment was assessed using a 95% confidence interval and p-value.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

A total of 393 pulmonary TB patients were included in this study with a 97.5% response rate. Eight patients were excluded from the study, since they were seriously ill and or not volunteer to respond. Most of the participants, 217 (55%) were males, and 157 (40%) were in the age group of 15–35 years. The mean (standard deviation (SD)) age of the study participants was 29.92 (± 9.65) years. Two hundred and forty four (62%) of the participants were residing in rural areas, 266 (67.7%) were married, 146 (37%) of them were not attending formal education (see Table 1).

Knowledge & behavior related characteristics

In this study, 8 (1.9%) of the study participants were current cigarette smoker and 30 (8%) were currently drinking alcohol, and 209 (53%) of study participants had low knowledge of TB. Table 2 shows the knowledge and behavior related characteristics of the study participants.

Clinical characteristics, health care accessibility and health seeking behaviors of the patients

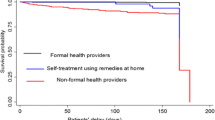

About one-third, 120 (30.5%) of the study participants had previous history of TB. Regarding patient condition before first visit to the facilities, 231 (58.8%) cases were actively working. Among the studied people, 298 (76%) were smear-positive cases and 93 (24%) cases were diagnosed by clinical evaluation and X-ray. The primary symptoms that patients experienced during the onset of their illness was coughing, 272 (69.2%). The magnitude of delay in TB treatment among the study participants was 223 (56.7%) (95% CI (51.8 – 61.6%), with the median (interquartile range) of delay in TB treatment of 30 (20–45) days (Table 3).

Of all the study participants, 216 (56%) TB cases travel over an estimated 5 km to reach to the nearest health facility from their home, with the mean (SD) of 5.8 (3,4) kilometers. High proportion, 272 (69.2%) of the study participants were treated with antibiotic before being diagnosis with TB in the health facilities (Table 3).

Factors associated with patient delay for TB treatment

In a bivariable logistic regression analysis place of residence, distance of the health facility, seeking antibiotic treatment before being diagnosed for TB, and knowledge of TB prevention and treatment, have shown association with patient delay in TB treatment. In a multivariable logistic regression analysis however, distance of the health facility from home, (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.0, 95% CI (1.3, 3.2)), seeking antibiotic treatment before being diagnosed for TB (AOR = 2.1, 95% CI (1.3, 3.5)), and the knowledge of TB prevention and treatments (AOR = 5.9, 95% CI (3.6, 9.8)), were significantly associated with delay in TB treatment (Table 4).

Discussion

Early detection of pulmonary TB cases and treating them are among the strategies of controlling TB. In this study, we found a high median delay time of TB treatment among the study participants. The prevalence of TB treatment delay among pulmonary TB patients in the study setting was high. Delay in TB treatment was associated with being treated with antibiotics before the diagnosis of TB, distance of the health facilities to get the TB care and lack of the knowledge related to TB.

The prevalence of patient delays in treatment of TB in the current study was nearly similar with the study reports from India 55.6.0% [32], Uganda 58% [33], Ghana 60% [34], Gamo Zone, 56.9% (29) and Gedeo Zone in the Southern Ethiopia, 50.9% [19]. However, our result was lower than the study reports from South western Iran 65.5% [6], and North Wollo Zone in North Ethiopia 62.3% [35], but it was higher than the findings from another reports from India, 49% [36] and South Africa, 40% [37]. The possible reasons for these discrepancies is that the difference in culture, socio-economy and time of conducting the studies.

The median patient delay in TB treatment in this study was consistent with the reports from Bahirdar, 30 days [38], Thailand was 30 days [9], Oromia region 35 days [39], and North Wollo Zone 36 days [35]. The present study finding however, is lower than that of the reports from Amara region Gondar town, 41 days [40] and Afar Region, 70 days [41]. This difference may be due to the differences in access to TB care (availability of diagnostic facilities). Another reason might be the difference in population characteristics which could be due to difference in health seeking behavior, the knowledge and geographical area. The current study finding is lower than many African reports. The median patient TB treatment delay was very high in most Africa countries, for instance in Ghana it was 59 days [34], in Uganda 58 days [33], and in Tanzania 48 days [42]. Also, there was a high delay in TB treatment in Peruvian Amazon, 61 days [10].

Concerning factors associated with delays in TB treatment, TB cases residing at a distance of at least 5 km from the nearest health facility were more likely to delay in TB treatment than those who were living below 5 km distance. This result was consistent with reports from Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia [19], South India [5], and Jima Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia [32]. TB cases from distant area may face difficulties to access the TB diagnostic and treatment services. They spend more transportation costs than patients from near areas. Thus it is advisable to provide support for patients living at distant place to reach to the health facilities and designing strategies to access such TB cases. One of the strategies could be community based TB case detection [43].

The current study has also showed that TB patients who received antibiotics treatment from somewhere else before the diagnosis of TB were more likely to be delayed in getting TB treatment. This result was consistent with the finding from Afar region [41] and Amhara region [39]. This could be due to the low awareness of the TB cases about TB symptoms. Most of the times, taking antibiotic treatment may initially lower the respiratory symptoms of TB. This could result patients to think that the illness is over and lead to patient to delay to be diagnosed and get timely TB treatment. Therefore, providing health education to such patients may be important to lower the risk of delay in TB treatment.

TB patients with low knowledge of TB had greater risk of delayed TB treatment. The result of this study was consistent with the reports from Thailand, South-India [44], North Wollo, Amhara Region Ethiopia [35], Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia [45], and Oromo Special Zone of the Amhara Region [39]. This finding could be justified by study patients with good knowledge about TB might have a better inclination for early seeking of proper medical care than those without. Having good knowledge of TB mode of transmission, prevention methods, knowledge about the diagnosis & treatment option are vital for early seeking of TB care.

Strengths and limitations of the study

In this study, we used relatively adequate sample size; as it is shown in Table 4 we have found narrow 95% confidence interval in measuring associations between the dependent and independent variables, especially for distance from home and antibiotic treatment before diagnosis variables. This can be considered as the strength of the study. Using a cross sectional study design which may not confirm the temporal relationship of the cause and effects could be considered as one of the limitations of the study. There may be information bias in the study as the data collection was relied on the participant’s self-reported duration of total delay and therefore this may subject to recall bias. Also there might be social desirability bias, especially on self-reporting of some sensitive issues like cigarette smoking status and alcohol drinking status.

Conclusions

The study showed that there is high median delay time in TB treatment and a high prevalence of delay in TB treatment among pulmonary TB patients in Dale district and Yirgalem town administration. Living at a distance of over 5 km from the nearest health facility, having low knowledge of TB & being treated with antibiotic before the current TB diagnosis were factors associated with delay in treatment of TB. Improving the health related knowledge of the public by providing health education to the community and solving problems related with service accessibility of health facilities may help to minimize the delay. Active case finding of TB using the health extension workers may also help in minimizing the delay in diagnosis and treatment due to service inaccessibility.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. Global TB Report 2022. Geneva, Swizerland.

Tegegne K. Health system delay in the treatment of tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2021.

Gebreegziabher SB, Bjune GA, Yimer SA. Patients ’ and health system ’ s delays in the diagnosis and treatment of new pulmonary tuberculosis patients in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia : a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;1–13.

Macneil A, Glaziou P, Sismanidis C, World TB, Day. — March 24, 2020. Global Epidemiology of Tuberculosis and Progress Toward Meeting Global Targets — Worldwide, 2018. 2020;69(11). In.

Rajeswari R, Chandrasekaran V, Suhadev M, Sivasubramaniam S, Sudha G, Renu G. Factors associated with patient and health system delays in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in South India. 2015;6:789–95.

Alavi SM, Bakhtiyariniya P, Albagi A. Factors Associated with Delay in diagnosis and treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. 2015;8(3):8–11.

Türkkani MH, Özdemir T, Özdilekcan Ç. Determination of related factors about diagnostic and treatment delays in patients with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis in Turkey. Turkish J Med Sci. 2020;50(5):1371–9.

Córdoba C, Luna L, Triana DM, Perez F, López L. Factors associated with delays in pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment initiation in Cali, Colombia. Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan Am J Public Heal. 2019;43:1–7.

Rattananupong T, Hiransuthikul N, Lohsoonthorn V, Chuchottaworn C, Medicine S. Factors Associated with Delay in Tuberculosis Treatment at 10. Tert Level Care Hosp. 2013;689–96.

Ford CM, Bayer AM, Gilman RH, Onifade D, Acosta C, Cabrera L, et al. Factors associated with delayed tuberculosis test-seeking behavior in the Peruvian Amazon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81(6):1097–102.

Ukwaja KN, Alobu I, Nweke CO, Onyenwe EC. Healthcare-seeking behavior, treatment delays and its determinants among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in rural Nigeria: a cross- sectional study. 2013;1–9.

Takarinda KC, Harries AD, Nyathi B, Ngwenya M, Mutasa-apollo T, Sandy C. Tuberculosis treatment delays and associated factors within the Zimbabwe national tuberculosis programme. 2015;1–12.

Soumare D, Baya B, Ouattara K, Kanoute T, M.Sy C, Karembé S, Guindo I, Coulibaly L, Kamian Y, Dakouo A, Sidibe F, Koné S, Kone D, Yossi O, Berthe G, Toloba Y. Identifying risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis delays in Mali a West-African Endemic Country. J Tuberculosis Res. 2022;10:45–59.

Makgopa S, Madiba S. Tuberculosis knowledge and delayed Health Care seeking among New Diagnosed Tuberculosis patients in Primary Health Facilities in an Urban District, South Africa. Health Serv Insights. 2021;14.

Kunjok DM, Mwangi JG, Mambo S, Wanyoike S. Assessment of delayed tuberculosis diagnosis preceding diagnostic confirmation among tuberculosis patients attending Isiolo County level four hospital, Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38:51. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2021.38.51.21508. PMID: 33854680; PMCID: PMC8017359.

Tsegaye D, Abiy E, Mesele T, et al. Delay in seeking Health Care and associated factors among pulmonary tuberculosis in North Wollo Zone, Northeast Ethiopia. Arch Clin Microbiol. 2016;7:3.

Adenager GS, Alemseged F, Asefa H, Gebremedhin AT. Factors Associated with Treatment Delay among Pulmonary Tuberculosis patients in Public and Private Health Facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Tuberc Res Treat. 2017;2017:5120841. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5120841. Epub 2017 Feb 27. PMID: 28348887; PMCID: PMC5350388.

Arja A, Godana W, Hassen H, Bogale B. Patient delay and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in Gamo Zone public health facilities, Southern Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7):e0255327.

Awoke N, Dulo B, Wudneh F. Total Delay in Treatment of Tuberculosis and Associated Factors among New Pulmonary TB patients in selected Health facilities of Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2017/18. Interdisciplinary Perspect Infect Dis. 2019;2019. Article ID 2154240.

Obsa MS, Daga WB, Wosene NG, Gebremedhin TD, Edosa DC, Dedecho AT, et al. Treatment seeking delay and associated factors among tuberculosis patients attending health facility in Ethiopia from 2000 to 2020: a systematic review and meta analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7):e0253746.

Fuge TG, Bawore SG, Solomon DW, et al. Patient delay in seeking tuberculosis diagnosis and associated factors in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:115.

Alene M, Assemie MA, Yismaw L, et al. Patient delay in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:797.

Getnet F, Demissie M, Worku A, Gobena T, Tschopp R, Seyoum B. Longer delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in Pastoralist setting, Eastern Ethiopia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:583–94.

Asres A, Jerene D, Deressa W. Delays to anti-tuberculosis treatment intiation among cases on directly observed treatment short course in districts of southwestern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;1–9.

Dixit K, Biermann O, Rai B, Aryal TP, Mishra G, De Siqueira-Filha NT, et al. Barriers and facilitators to accessing tuberculosis care in Nepal: a qualitative study to inform the design of a socioeconomic support intervention. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):1–12.

Li Y, Ehiri J, Tang S, Li D, Bian Y, Lin H, et al. Factors associated with patient, and diagnostic delays in Chinese TB patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:156.

Fanta A, Daniel A. Delay in Healthcare-seeking behavior and its Associated factors among tuberculosis patients attending TB Clinic in Hawassa City Health Facilities in Sidamma Region, Hawassa Ethiopia, 2022. Int Arch Nurs Health Care. 2023;9:180.

Sidama Region Annual Health Sector Report. 2014, Hawassa Ethiopia. In.

MOH. Guideline for clinical and programmatic management of TB, leprosy and TB/HIV in Ethiopia. Fifth edition. APRIL, 2012 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Lambert ML, Van der Stuyft P. Delays to tuberculosis treatment: shall we continue to blame the victim? Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(10):945-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01485.x. PMID: 16185227.

Kiwuwa MS, Charles K, Harriet MK. Patient and health service delay in pulmonary tuberculosis patients attending a referral hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2005;5(1):122.

Ado M, Woldemichael K, Atomsa A. Determinants of delay in seeking health care among tuberculosis patients attending tuberculosis clinic at health service in Jima, Ethiopia: a case control study. 2017.

Buregyeya E, Criel B, Nuwaha F, Colebunders R. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in Wakiso and Mukono districts, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–10.

Osei E, Akweongo P, Binka F. Factors associated with delay in diagnosis among tuberculosis patients in Hohoe municipality, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:721–31.

Tsegaye D, Abiy E, Mesele T, et al. Delay in seeking health care and associated factors among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in north Wollo Zone, Northeast Ethiopia: Institution Based cross-sectional study. Arch Clin Microbiol. 2016;7:3.

Bojovic O, Medenica M, Zivkovic D, Rakocevic B, Trajkovic G, Kisic-Tepavcevic D, et al. Factors associated with patient and health system delays in diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in Montenegro, 2015–2016. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193997.

Chiposi L, Cele LP, Mokgatle M. Prevalence of delay in seeking tuberculosis care and the health care seeking behaviour profile of tuberculous patients in a rural district of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;39:27.

Mekonnen YA, Abebe L, Fentahun N, Belay SA, Kassa AW. Delay for first consultation and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in Bahir Dar town administration, North West Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2014;2(4):140–5.

Abdu M, Balchut A, Girma E, Mebratu W. Patient Delay in Initiating Tuberculosis Treatment and Associated factors in Oromia Special Zone, Amhara Region. Pulmonary Medicine; Volume 2020. Article ID 9505083.

Bogale S, Diro E, Shiferaw AM, Yenit MK. Factors associated with the length of delay with tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment among adult tuberculosis patients attending at public health facilities in Gondar town, Northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):145.

Belay M, Bjune G, Ameni G, Abebe F. Diagnostic and treatment delay among tuberculosis patients in Afar Region, Ethiopia : a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1.

Hinderaker SG, Madland S, Ullenes M, Ullenes M, Enarson DA, Rusen ID, et al. Treatment delay among tuberculosis patients in Tanzania: data from FIDELIS Initiative. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:306.

Burke RM, Nliwasa M, Feasey HRA, Chaisson LH, Golub JH, Naufal F, Shapiro AE, Ruperez M, Telisinghe L, Ayles H, Corbett EL, Pherson PM. Community-based active case-finding interventions for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(5):e283–99.

Paramasivam S, Thomas B, Chandran P, Thayyil J, George B, Sivakumar CP. Diagnostic delay and associated factors among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Kerala. J Family Med Prim Care. 2017;6(3):643–8.

Haboro GG, Handiso TB, Gebretsadik LA. Health Care System Delay of Tuberculosis Treatment and its correlates among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Hadiya Zone Public Health Facilities, Southern Ethiopia. J Infect Dis Epidemiol. 2019;5:077.

FDRE Ministry of Science and Technology. National Research Ethics Review Guideline Fifth Edition. https://www.studocu.com/row/u/12433566?sid=01714558687. 2011.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Hawassa University for providing fund to carryout data collection. We also want to thanks data collectors, the study participants, and Dale district health facilities for providing permission.

Funding

Hawassa University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DD: Data curation, visualization, investigation, conceptualization, formal analysis, writing original draft. EMW: Data curation, conceptualization, investigation, review and editing. DL: Data curation, conceptualization, investigation, review and editing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Declarations under principles of Helsinki and the Ethiopian National Research Ethics guideline were maintained in the research process [46]. Data collection was done after obtaining ethical clearance letter from the Hawassa University Institutional Review Board (IRB) of a college of Medicine and Health Sciences Reference number IRB 065/14, and a support letter from Sidama Regional State Health Bureau and Dale District Health Office and Yirgalem Town Health Office. Formal letter of permission was provided to each Health facility. Informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. Participants were informed that participation was on voluntary basis, they have full right to refuse participation or withdraw from the study at any stage of the interview, without losing any of their rights of receiving TB care in the facilities and they were not forced to stay in the study. Confidentiality of patient information was secured. Data were collected anonymously. The ethics declaration in your manuscript does not mention a norm or standard according to which your research was conducted (e.g., “in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki”). Please provide the name of the norm or standard observed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All the authors have no competing interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rima, D.D., Legese, D. & Woldesemayat, E.M. Tuberculosis treatment delay and associated factors among pulmonary tuberculosis patients at public health facilities in Dale District and Yirgalem Town administration, Sidama Region, South Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 24, 517 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09397-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09397-8