Abstract

Background

Roseomonas mucosa (R. mucosa) is a pink-pigmented, Gram-negative short rod bacterium. It is isolated from moist environments and skin, resistant to multiple drugs, including broad-spectrum cephalosporins, and a rare cause of infection with limited reports. R. mucosa mostly causes catheter-related bloodstream infections, with even fewer reports of skin and soft tissue infections.

Case presentation

A 10-year-old boy received topical steroid treatment for sebum-deficient eczema. A few days before the visit, he was bitten by an insect on the front of his right lower leg and scratched it due to itching. The day before the visit, redness, swelling, and mild pain in the same area were observed. Based on his symptoms, he was diagnosed with cellulitis. He was treated with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and his symptoms improved. Pus culture revealed R. mucosa.

Conclusions

We report a rare case of cellulitis caused by R. mucosa. Infections caused by rare organisms that cause opportunistic infections, such as R. mucosa, should be considered in patients with compromised skin barrier function and regular topical steroid use. Gram stain detection of organisms other than Gram-positive cocci should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Roseomonas is a slow-growing Gram-negative coccobacilli with pink pigmentation. It was first described in 1993 [1]. Most Roseomonas species are environmental bacteria, but some species have been isolated from the skin [2]. The major pathogens in humans are Roseomonas gilardii, Roseomonas cervicalis, and Roseomonas mucosa (R. mucosa) [2,3,4].

Reports of R. mucosa infection in humans are limited; however, there have been reports of catheter-related bloodstream infections [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] and infections in immunocompromised patients. Cases of bacteremia [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18], peritonitis [18,19,20,21], meningitis [22], infection of soft tissues [4], spinal epidural abscess [23], pyogenic spondylitis [16], cholangitis [11], subretinal abscess [24], infection of the root canal [25], and liver abscess [26] have also been reported. R. mucosa is resistant to broad-spectrum cephalosporins [2, 3].

Many patients in these reports were immunocompromised [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, 17,18,19,20,21, 24] or had catheter-related [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] or postoperative infections [16, 22, 23], with few reports of infection in patients without these characteristics [26]. Reports of skin and soft tissue infections are also rare. Herein, we report a case of cellulitis caused by R. mucosa in a non-immunocompromised pediatric patient.

Case presentation

A 10-year-old boy with no history of immunosuppression had comorbidities, including allergic rhinitis and sebum-deficient eczema, which was treated with topical dexamethasone propionate ointment 0.1%. A few days before the visit, he had been bitten by an insect on the anterior surface of his right lower leg and had scratched it due to itching. The day before the visit, redness and mild pain were observed in the same area, and the patient visited the pediatric department of this hospital.

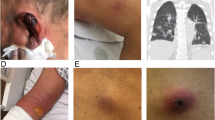

The vital signs at the time of the patient’s visit to our hospital were as follows: body temperature, 36.1 °C; pulse, 79 beats/minute; and saturation of percutaneous arterial oxygen, 97% (room air). The patient was 140.0 cm tall, weighed 38.0 kg, and had erythema, heat sensation, and swelling with indistinct margins on the anterior aspect of the right lower leg measuring 7 × 7 cm in diameter, with mild pain and itching in the same area. In the center of the erythema, a crust of about 3 × 1 mm and a small amount of pus was observed. Gram staining of the pus showed Gram-negative short bacilli. The right inguinal lymph node was not palpable.

Based on the symptoms and findings, he was diagnosed with right lower leg cellulitis. The patient had a Gram-negative short bacillus, which was atypical for cellulitis, unlike Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, usually associated with cellulitis (Fig. 1). The patient was treated with oral sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and topical betamethasone valerate/gentamicin hydrochloride ointment 0.12%. Because the pruritus was severe, topical betamethasone was used in addition to topical antibiotics. After 3 days, the area of erythema was reduced to approximately 3 × 1 cm, and the pain and itching disappeared. Since the symptoms had largely improved, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim was taken orally for 5 days, and the symptoms resolved completely. Cultures of pus detected two types of bacteria, but normal culture methods could not identify one type of bacteria. The sample was analyzed using a Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time of Flight Mass Spectrometer (MALDI-TOS MS) and identified as R. mucosa (score = 2.52). The other bacterium was Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus. Gram staining showed that it was a Gram-negative bacillus. We considered R. mucosa to be the causative bacterium.

However, the symptoms disappeared when the bacterium was identified as R. mucosa. Susceptibility tests were performed by the broth microdilution method based on standards reported by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (Table 1). Susceptibility testing for sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim was not performed. No additional treatment was given because the patient was clinically symptom-free. The patient was followed up until one month after onset, and no relapse of symptoms was observed.

Discussion and conclusions

We encountered a case of cellulitis caused by R. mucosa. Since R. mucosa exists in soil and moist environments and is a type of resident skin fungus, it rarely causes infections.

Reports of infections caused by R. mucosa are limited, and a comprehensive literature review was conducted. A PubMed search using the keyword “Roseomonas mucosa” yielded 44 articles, 5 related to skin or soft tissue infections (PubMed was last searched on May 20, 2023). One study reported soft tissue infection in an 8-month-old boy with spinal cord engagement syndrome. He was treated with vancomycin and cefotaxime and was cured [4]. Another case involved the detection of R. mucosa in tattoo ink sold in the U.S. [27]. Topical administration of R. mucosa from healthy volunteers to patients with atopic dermatitis was reported to improve symptoms [28,29,30].

Although whole-genome sequencing is the appropriate method for detecting R. mucosa, MALDI-TOF MS or 16 S rRNA gene analysis can identify the bacteria for easy and reliable detection in the laboratory. VITEK 2 (bioMérieux, Germany) incorrectly identified this bacterium as Roseomonas gilardii or Rhizobium radiobacter. However, MALDI-TOF MS and 16 S rRNA genetic analysis reliably identified the species [31]. R. mucosa is consistently susceptible to amikacin and imipenem, frequently susceptible to ciprofloxacin and ticarcillin, and essentially resistant to ampicillin, ceftazidime, and cefepime. There are also reports of imipenem/cilastatin-resistant strains [10]; however, its susceptibility to ceftriaxone and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim has limited reports [3]. In this case, the patient was resistant to penicillin and cephalosporins but susceptible to carbapenems, quinolones, and aminoglycosides (Table 1). Despite its clinical validity, the susceptibility to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim was not tested due to contractual constraints with an outside laboratory.

R. mucosa has been frequently reported as an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, 17,18,19,20,21, 24] and those with catheter-related bloodstream [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] or postoperative [16, 22, 23] infections. In the present case, the skin barrier function was originally impaired due to sebum-deficient eczema, and the local immunosuppressive effects caused by topical steroids were assumed to have contributed to an increased susceptibility to infection. In addition, he reported a history of playing in an open and wet area beside his house and was possibly infected by the insects in that area.

In microbiome studies, the area of the skin harboring Gram-negative bacteria overlaps with the area most affected by atopic dermatitis. Bacterial carriage in this region is significantly reduced in patients with atopic dermatitis. Topical administration of R. mucosa has been reported to improve symptoms. However, the R. mucosa used for topical administration is a specific strain isolated from healthy volunteers, and animal studies using R. mucosa derived from atopic patients have reported no change or worsening of local symptoms [28]. We believe that the reason R. mucosa did not cause cellulitis or erysipelas in previous reports is that R. mucosa was administered from healthy volunteers. However, if the R. mucosa was obtained from a patient with a compromised skin barrier function, as in the present case, cellulitis may have occurred.

When skin infections such as cellulitis are observed in patients with compromised skin barrier function, as in this case, or in patients who regularly use topical steroids, one should be aware of rare organisms that can cause opportunistic infections. In particular, when bacteria other than Gram-positive cocci are detected using Gram staining, attention should be paid to drug-resistant bacteria such as R. mucosa.

This study has some limitations. First, as this is a case report, it is difficult to generalize the findings to other pediatric patients with hypodermic eczema. Furthermore, the long-term health effects of R. mucosa infection remain unknown.

In conclusion, we report a rare case of cellulitis caused by R. mucosa. In patients with compromised skin barrier function, regular topical steroid use, and non-Gram-positive cocci detected by Gram staining, it is also necessary to pay attention to infectious diseases caused by rare opportunistic organisms, including R. mucosa.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- R. mucosa :

-

Roseomonas mucosa

- MALDI-TOS MS:

-

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time of Flight Mass Spectrometer

References

Rihs JD, Brenner DJ, Weaver RE, Steigerwalt AG, Hollis DG, Yu VL. Roseomonas, a new genus associated with bacteremia and other human Infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3275–83.

Romano-Bertrand S, Bourdier A, Aujoulat F, Michon AL, Masnou A, Parer S, et al. Skin microbiota is the main reservoir of Roseomonas mucosa, an emerging opportunistic pathogen so far assumed to be environmental. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:737e1–7.

Han XY, Pham AS, Tarrand JJ, Rolston KV, Helsel LO, Levett PN. Bacteriologic characterization of 36 strains of Roseomonas species and proposal of Roseomonas mucosa sp nov and Roseomonas gilardii subsp rosea subsp nov. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:256–64.

Wang CM, Lai CC, Tan CK, Huang YC, Chung KP, Lee MR, et al. Clinical characteristics of Infections caused by Roseomonas species and antimicrobial susceptibilities of the isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;72:199–203.

Dé I, Rolston KV, Han XY. Clinical significance of Roseomonas species isolated from catheter and blood samples: analysis of 36 cases in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1579–84.

Elshibly S, Xu J, McClurg RB, Rooney PJ, Millar BC, Alexander HD, et al. Central line-related bacteremia due to Roseomonas mucosa in a patient with diffuse large B-cell non-hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:611–4.

Christakis GB, Perlorentzou S, Alexaki P, Megalakaki A, Zarkadis IK. Central line-related bacteraemia due to Roseomonas mucosa in a neutropenic patient with acute myeloid Leukaemia in Piraeus, Greece. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:1153–6.

Bard JD, Deville JG, Summanen PH, Lewinski MA. Roseomonas mucosa isolated from bloodstream of pediatric patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3027–9.

Al-Anazi KA, AlHashmi H, Abdalhamid B, AlSelwi W, AlSayegh M, Alzayed A, et al. Roseomonas bacteremia in a recipient of an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2013;15:E144–7.

Michon AL, Saumet L, Bourdier A, Haouy S, Sirvent N, Marchandin H. Bacteremia due to imipenem-resistant Roseomonas mucosa in a child with acute lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:e165–8.

Kim YK, Moon JS, Song KE, Lee WK. Two cases of bacteremia due to Roseomonas mucosa. Ann Lab Med. 2016;36:367–70.

Abu Choudhury M, Wailan AM, Sidjabat HE, Zhang L, Marsh N, Rickard CM, et al. Draft genome sequence of Roseomonas mucosa strain AU37, isolated from a peripheral intravenous catheter. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e00128–17.

Kimura K, Hagiya H, Nishi I, Yoshida H, Tomono K. Roseomonas mucosa bacteremia in a neutropenic child: a case report and literature review. IDCases. 2018;14:e00469.

Okamoto K, Ayibieke A, Saito R, Ogura K, Magara Y, Ueda R, et al. A nosocomial cluster of Roseomonas mucosa bacteremia possibly linked to contaminated hospital environment. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26:802–6.

Sipsas NV, Papaparaskevas J, Stefanou I, Kalatzis K, Vlachoyiannopoulos P, Avlamis A. Septic arthritis due to Roseomonas mucosa in a rheumatoid arthritis patient receiving infliximab therapy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;55:343–5.

Kim KY, Hur J, Jo W, Hong J, Cho OH, Kang DH, et al. Infectious spondylitis with bacteremia caused by Roseomonas mucosa in an immunocompetent patient. Infect Chemother. 2015;47:194–6.

Shao S, Guo X, Guo P, Cui Y, Chen Y. Roseomonas mucosa infective endocarditis in patient with systemic Lupus Erythematosus: case report and review of literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:140.

Beucler N, Meyer M, Choucha A, Seng P, Dufour H. Peritonitis caused by Roseomonas mucosa after ventriculoperitoneal shunt revision: a case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020;162:2459–62.

Boyd MA, Laurens MB, Fiorella PD, Mendley SR. Peritonitis and technique failure caused by Roseomonas mucosa in an adolescent infected with HIV on continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3801–4.

Matsukuma Y, Sugawara K, Shimano S, Yamada S, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T, et al. A case of bacterial Peritonitis caused by Roseomonas mucosa in a patient undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. CEN Case Rep. 2014;3:127–31.

Roy S, Patel S, Kummamuru H, Garcha AS, Gupta R, Adapa S. Roseomonas mucosa-induced Peritonitis in a patient undergoing continuous cycler peritoneal dialysis: case report and literature analysis. Case Rep Nephrol. 2021;2021:1979332.

Waris RS, Ballard M, Hong D, Seddik TB. Meningitis due to Roseomonas in an immunocompetent adolescent. Access Microbiol. 2021;3:000213.

Maraki S, Bantouna V, Lianoudakis E, Stavrakakis I, Scoulica E. Roseomonas spinal epidural abscess complicating instrumented posterior lumbar interbody fusion. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2458–60.

Bhende M, Karpe A, Arunachalam S, Therese KL, Biswas J. Endogenous endophthalmitis due to Roseomonas mucosa presenting as a subretinal abscess. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2017;7:5.

Diesendorf N, Köhler S, Geißdörfer W, Grobecker-Karl T, Karl M, Burkovski A. Characterisation of Roseomonas mucosa isolated from the root canal of an infected tooth. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:212.

Spindel J, Grigorov M, Baker M, Marsano L. Cardiac tamponade due to perforation of a Roseomonas mucosa pyogenic hepatic abscess as initial presentation of hepatoid carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15:e248947.

Nho SW, Kim SJ, Kweon O, Howard PC, Moon MS, Sadrieh NK, et al. Microbiological survey of commercial tattoo and permanent makeup inks available in the United States. J Appl Microbiol. 2018;124:1294–302.

Myles IA, Earland NJ, Anderson ED, Moore IN, Kieh MD, Williams KW, et al. First-in-human topical microbiome transplantation with Roseomonas mucosa for atopic dermatitis. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e120608.

Paller AS, Kong HH, Seed P, Naik S, Scharschmidt TC, Gallo RL et al. The microbiome in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:26–35. Erratum in: J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1660.

Myles IA, Moore IN, Castillo CR, Datta SK. Differing virulence of healthy skin commensals in mouse models of Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:451.

Rudolph WW, Gunzer F, Trauth M, Bunk B, Bigge R, Schröttner P. Comparison of VITEK 2, MALDI-TOF MS, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and whole-genome sequencing for identification of Roseomonas mucosa. Microb Pathog. 2019;134:103576.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Mr. Kazumi Mishima, a clinical laboratory technologist at the Center for Community Medicine in North-Western Gifu Prefecture National Health Insurance Shirotori Hospital, for his cooperation in obtaining the image data of this case.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YM managed the case and prepared and revised the manuscript. TK assisted with the preparation and revision of the manuscript. HH and TG assisted with data analysis and revision of the manuscript. All co-authors approve the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All co-authors take full responsibility for the integrity of the report and the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Center for Community Medicine ethics committee in North-Western Gifu Prefecture waived this case report’s ethical approval and consent requirement due to the study’s retrospective nature. This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and his mother to publish this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsuhisa, Y., Kenzaka, T., Hirose, H. et al. Cellulitis caused by Roseomonas mucosa in a child: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 23, 867 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08875-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08875-9