Abstract

Background

Fungal infections, other than candidiasis and aspergillosis, are an uncommon entity. Despite this, emerging pathogens are a growing threat. In the following case report, we present the case of an immunocompromised patient suffering from two serious opportunistic infections in the same episode: the first of these, Nocardia multilobar pneumonia; and the second, skin infection by Scedosporium apiospermum. These required prolonged antibacterial and antifungal treatment.

Case presentation

This case is a 71-year-old oncological patient admitted for recurrent pneumonias that was diagnosed for Nocardia pulmonary infection. Nervous system involvement was discarded and cotrimoxazole was started. Haemorrhagic skin ulcers in the lower limbs appeared after two weeks of hospital admission. We collected samples which were positive for Scedosporium apiospermum and we added voriconazole to the treatment. As a local complication, the patient presented a deep bruise that needed debridement. We completed 4 weeks of intravenous treatment with slow improvement and continued with oral treatment until the disappearance of the lesions occurs.

Conclusions

Opportunistic infections are a rising entity as the number of immunocompromised patients is growing due to more use of immunosuppressive therapies and transplants. Clinicians must have a high suspicion to diagnose and treat them. A fluid collaboration with Microbiology is necessary as antimicrobial resistance is frequent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients with neoplastic diseases are frequently at high risk of developing opportunistic infections. This susceptibility can be attributed to factors such as cancer or treatment-induced neutropenia, cellular immune defects, or local conditions like bronchial tree or biliary tract obstruction [1]. In this case, our patient experienced two opportunistic infections, which we will now present.

Nocardia is a type of aerobic gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium belonging to the Actinomycetes genus, primarily found in soil. Human infection is commonly caused by inhalation of Nocardia into the lungs. Although it primarily affects the lungs, it can also impact the brain, skin, eyes, or spread throughout the body. Nocardia infections are typically seen in individuals with compromised immune systems or chronic lung disease [2]. Symptoms often manifest as subacute pneumonia, characterized by dyspnoea, cough, and purulent expectoration. Fever is usually absent. Radiologically, common findings include consolidation, nodules, and cavitation. The diagnosis of Nocardia infection relies on culture-based techniques, typically utilizing bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or sputum samples. Subsequently, molecular techniques are employed for species identification. Nocardia infections are usually susceptible to treatment with amikacin, linezolid, and cotrimoxazole [3].

Scedosporium apiospermum is a filamentous fungus present in the environment as they have been found in rural soils, polluted water and composts [4]. It usually causes infection in severely immunocompromised patients, although it may affect healthy individuals with penetrating trauma. It can either present as a colonization (in cystic fibrosis, external ear or respiratory fungal ball), local infection (usually in skin, soft tissues and bone infection) or disseminated infection, with predilection for skin, sinuses, lungs and central nervous system [4,5,6]. The diagnosis is reached by conventional culture, although some diagnostic molecular methods have been tested. There are no solid recommendations about treatment. In vitro and in vivo data show that S. apiospermum is resistant to amphotericin-B and flucytosine and demonstrates variable susceptibility to itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole and micafungin. Currently, with the available data, voriconazole represents the first-line treatment. Surgery removal of localised lesions improves the outcome. The resolution of the factors that produce immunosuppression is the key for the treatment success [7].

Case presentation

We present the case of a 71-year-old man with rectal adenocarcinoma admitted for fever and dyspnoea in March of 2022. The patient did not have any allergies; he was a former smoker and had hypertension, dyslipidaemia, benign prostatic hyperplasia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In 2019 he was diagnosed of rectal adenocarcinoma and he received treatment with capecitabine, radiotherapy and underwent a surgery (abdominoperineal resection). In September of 2020 he presented a pulmonary metastasis therefore he started FOLFOX (oxaliplatin in combination with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin) and Bevacizumab for 9 cycles and afterwards capecitabine and Bevacizumab for 3 more cycles. Due to pulmonary progression, he started the second line with FOLFORI (folinic acid, fluorouracil and irinotecan) and Cetuximab for 4 cycles until February of 2022.

In March of 2022 he had already been admitted twice for fever and dyspnoea, with a radiological image compatible with pneumonia. In the first admission he received treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and azithromycin and in the second hospitalization he was treated with piperacillin-tazobactam and levofloxacin as health care associated pneumonia. Cultures were negative, so he completed empirical treatment showing progressive clinical and analytical improvement. On both occasions, he was discharged afebrile, hemodynamically stable and without oxygen therapy needed.

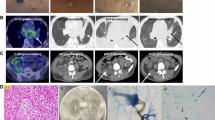

In the current episode, the 3rd admission in March of 2022, he is readmitted due to the reappearance of the symptoms a few days after being discharged. He presented elevated analytic acute phase reactants and radiographic worsening with multilobar involvement (Fig. 1). Empirical treatment was started with piperacillin-tazobactam 4 g/6 h and levofloxacin 500 mg/24 h. Also, a thoracic CT scan and a bronchoscopy were performed. The thoracic CT scan showed pulmonary lesions with necrosis and cavitation in both lungs, the metastasis had not changed in comparison with the previous scan. The bronchoscopy showed purulent secretions from both lungs, specially the right one. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica (> 100.000 CFU/ml) was successfully identified by MALDI-TOF in the samples of bronchial aspirate. Antibiotic treatment was changed to cotrimoxazole 800/120 mg/12 h, and brain infection was ruled out with a CT scan.

Two weeks later the patient presented haemorrhagic skin ulcers in the lower limbs, over an erythematous plaque (Fig. 2). The ulcers measured 5 mm of diameter and secreted a brown material. Both, a skin biopsy and a culture were performed. Scedosporium apiospermum was identified by calcofluor and lactophenol blue, as well as through MALDI-TOF technique in the samples from the skin biopsy. There were not any predisposing factors known as the patient had not had any trauma nor drowing incidents. The biopsy showed abcessified areas and fungal structures with 90º ramification with positivity for Hematoxylin-eosin, Grocott and Periodic acid-Schiff staining (Fig. 3). Voriconazole 300 mg/12 h was started after the results and was administered during 6 weeks at hospital admission with slow improvement. Deep infection was ruled out by lower limbs CT scan. As a local complication, the patient presented a deep bruise that needed debridement. The initial 4 weeks the patient received intravenous voriconazole and afterwards switched to oral treatment for the long term.

Discusion and conclusions

Oncological patients are at a heightened risk of developing opportunistic infections, with approximately 80% of Nocardia infections occurring in immunocompromised individuals [2]. A review of 136 episodes of Nocardia infection at a cancer center revealed that 43.4% were associated with solid tumors, similar to our patient’s case, while the remainder were linked to haematological diseases [8]. Clinical differences exist between infections in immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. Immunocompromised individuals are more likely to experience cavitation lesions in the lungs, disseminated infection, and eye involvement. Furthermore, mortality rates are significantly higher in this group, reaching 27% compared to 7% in immunocompetent patients [2].

Regarding identification, a multi-center study conducted in Spain found that the most commonly isolated species is N. cyriacigeorgica, as observed in our case [3]. Antimicrobial susceptibility varies among Nocardia species. In Spain, amikacin and linezolid exhibit activity against all species in a majority of cases (98.3% and 99.4% respectively), while carbapenems and clotrimazole are effective against most species (90.5% and 83.8% respectively) [9].

On the other hand, fungal infections are a growing entity globally. Emerging pathogens such as Scedosporium should not be ignored, as it was the second most frequently isolated filamentous fungus in a population-based survey in Spain [10]. Epidemiological studies in other countries also confirm this trend [11].

Scedosporium infection has been associated with corticosteroid use, chronic lung disease, diabetes and haematological malignancy and not usually with solid tumors [12,13,14,15] In the case of our patient, he had been receiving corticosteroid treatment while undergoing treatment for Nocardia pneumonia. Scedosporium has also been described in immunocompetent hosts after drowning in polluted wated or penetrating trauma [5, 6]. The most common forms of infection in immunocompetent hosts are keratitis, endophthalmitis, otitis, sinusitis, central nervous system infections, osteoarticular and soft tissue infections and pneumonia. In immunocompromised patients, infections can involve any organ with a predilection for skin (as in our case), sinuses, lungs and central nervous system [4, 5, 7, 16].

The histological study and the microbiological culture are the main tools to reach a diagnosis. At the moment, molecular techniques are reserved for studies [17]. Histopathologic examination is helpful in determining the presence of an invasive fungal infection (e.g. positivity in the specific fungal stains, septate hyphae…), but it is not possible to establish the causative pathogen without culture because many molds have a similar appearance. Culture is also important for antifungal susceptibility testing [4, 5]. In a Spanish study analysing 60 isolates of Scedosporium, most of the strains (with exception of S. prolificans) were found susceptible for voriconazole and micafungin [18].

The prognosis is poor due to the comorbidities of patients and the multi-resistance of the Scedosporium species, with high MICs (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) to most of antifungals tested. S. apiospermum shows in vitro susceptibility to voriconazole, posaconazole and in some cases to echinocandins [10]. Also, species and site of infection were shown to be statistically significant prognostic factors for overall global response [12]. Surgical resection or debridement is key in immunosuppressed patients. Its indication in the ESCMID and ECMM guidelines are the following: haemoptysis from a single cavitary lung lesion, progressive cavitary lung lesion, osteomyelitis or septic arthritis, resection of infected or colonized tissue before commencing immunosuppressive agents to prevent dissemination and infiltration into the pericardium great vessels, bone or thoracic sort tissue [4].

Overall mortality is 30% for immunocompetent patients and 44% for immunocompromised hosts [12]. The most at-risk patients are hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and the ones suffering from disseminated disease. Patients receiving voriconazole have longer survival time compared to patients treated with amphotericin B [4, 7, 12]. In a retrospective study of 107 voriconazole treated patients, the median therapy duration in treatment success cases was 180 days. Best success rate was seen in skin/subcutaneous tissues [7].

In conclusion, emerging fungal infections are increasing globally. These species are more difficult to diagnose and treat due to their resistance, which implies a higher mortality [19]. Therefore, clinicians must be more aggressive in the diagnosis, ruling out complications and treatment (including surgery if necessary) [4, 7]. More studies are needed to provide more information on all these aspects.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Safdar A, Bodey G, Armstrong D. Infections in Patients with Cancer: Overview. Principles and Practice of Cancer Infectious Diseases. 4 gener 2011;3–15.

Steinbrink J, Leavens J, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Manifestations and outcomes of nocardia infections. Medicine (Baltimore). 5 octubre 2018;97(40):e12436.

Ercibengoa M, Càmara J, Tubau F, García-Somoza D, Galar A, Martín-Rabadán P, et al. A multicentre analysis of Nocardia pneumonia in Spain: 2010–2016. Int J Infect Dis 1 gener. 2020;90:161–6.

Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, van Diepeningen A, Caira M, Munoz P et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 1 abril 2014;20:27–46.

Walsh TJ, Groll A, Hiemenz J, Fleming R, Roilides E, Anaissie E. Infections due to emerging and uncommon medically important fungal pathogens. Clin Microbiol Infect març. 2004;10(Suppl 1):48–66.

Bouza E, Muñoz P. Invasive infections caused by Blastoschizomyces capitatus and Scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Infect 1 gener. 2004;10:76–85.

Troke P, Aguirrebengoa K, Arteaga C, Ellis D, Heath CH, Lutsar I, et al. Treatment of scedosporiosis with voriconazole: clinical experience with 107 patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother maig. 2008;52(5):1743–50.

Wang HL, Seo YH, LaSala PR, Tarrand JJ, Han XY. Nocardiosis in 132 patients with Cancer: microbiological and clinical analyses. Am J Clin Pathol 1 octubre. 2014;142(4):513–23.

Valdezate S, Garrido N, Carrasco G, Medina-Pascual MJ, Villalón P, Navarro AM, et al. Epidemiology and susceptibility to antimicrobial agents of the main Nocardia species in Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother 1 març. 2017;72(3):754–61.

Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Mellado E, Peláez T, Pemán J, Zapico S, Alvarez M, et al. Population-based survey of filamentous fungi and antifungal resistance in Spain (FILPOP Study). Antimicrob Agents Chemother juliol. 2013;57(7):3380–7.

Slavin M, van Hal S, Sorrell TC, Lee A, Marriott DJ, Daveson K, et al. Invasive infections due to filamentous fungi other than aspergillus: epidemiology and determinants of mortality. Clin Microbiol Infect maig. 2015;21(5):490e1–10.

Seidel D, Meißner A, Lackner M, Piepenbrock E, Salmanton-García J, Stecher M, et al. Prognostic factors in 264 adults with invasive Scedosporium spp. and Lomentospora prolificans infection reported in the literature and FungiScope®. Crit Rev Microbiol febrer. 2019;45(1):1–21.

Heath CH, Slavin MA, Sorrell TC, Handke R, Harun A, Phillips M, et al. Population-based surveillance for scedosporiosis in Australia: epidemiology, disease manifestations and emergence of Scedosporium aurantiacum infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 1 juliol. 2009;15(7):689–93.

Lamaris GA, Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Safdar A, Raad II, Kontoyiannis DP. Scedosporium infection in a Tertiary Care Cancer Center: a review of 25 cases from 1989–2006. Clin Infect Dis 15 desembre. 2006;43(12):1580–4.

Tóth EJ, Nagy GR, Homa M, Ábrók M, Kiss I, Nagy G, et al. Recurrent scedosporium apiospermum mycetoma successfully treated by surgical excision and terbinafine treatment: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 14 abril. 2017;16:31.

Husain S, Muñoz P, Forrest G, Alexander BD, Somani J, Brennan K, et al. Infections due to Scedosporium apiospermum and scedosporium prolificans in transplant recipients: clinical characteristics and impact of antifungal agent therapy on outcome. Clin Infect Dis 1 gener. 2005;40(1):89–99.

Chen SCA, Halliday CL, Hoenigl M, Cornely OA, Meyer W. Scedosporium and Lomentospora Infections: Contemporary Microbiological Tools for the Diagnosis of Invasive Disease. J Fungi (Basel). 4 gener 2021;7(1):23.

Lackner M, Rezusta A, Villuendas MC, Palacian MP, Meis JF, Klaassen CH. Infection and colonisation due to Scedosporium in Northern Spain. An in vitro antifungal susceptibility and molecular epidemiology study of 60 isolates. Mycoses. 2011;54(s3):12–21.

Álvarez-Uría A, Guinea JV, Escribano P, Gómez-Castellá J, Valerio M, Galar A et al. Invasive Scedosporium and Lomentosora infections in the era of antifungal prophylaxis: A 20-year experience from a single centre in Spain. Mycoses. 4 agost 2020.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Each author has contributed significantly to the development of the manuscript. GM and LA were the main contributors to drafting the manuscript. CC performed the anatomopathological study. VH, GS, ML and RM performed the manuscript review and contributed to the intellectual content of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gavalda, M., Lorenzo, A., Vilchez, H. et al. Skin lesions by Scedosporium apiospermum and Nocardia pulmonary infection in an oncologic patient: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 23, 523 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08484-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08484-6