Abstract

Background

Bacterial infective endocarditis caused by Proteus mirabilis is rare and there are few cases in the literature. The natural history and treatment of this disease is not as clear but presumed to be associated with complicated urinary tract infection (cUTI).

Case presentation

A 65-year-old female with a history of rheumatoid arthritis, factor V Leiden hypercoagulability, and prior saddle pulmonary embolism presented to the emergency department following a mechanical fall. Computed Tomography showed evidence of acute/subacute splenic emboli. Complicated UTI was likely secondary to a ureteral stone. Blood and urine cultures also grew out P. mirabilis. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a mobile echogenic density on the anterior mitral valve (MV) leaflet consistent with a vegetation. The patient underwent MV replacement, and P. mirabilis was isolated from the surgically removed valve.

Conclusions

We hypothesize that the patient’s immunocompromised status following steroid and Janus Kinase inhibitor usage for rheumatoid arthritis contributed to Gram-negative bacteremia following P. mirabilis UTI, ultimately seeding the native MV. Additional studies with larger numbers of Proteus endocarditis cases are needed to investigate an association between immunosuppression and Proteus species endocarditis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bacterial infective endocarditis (IE) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and has become one of the leading life-threatening infection syndromes [1]. IE caused by Proteus mirabilis is exceedingly rare, and only a limited number of endocarditis due to Proteus spp. have been documented in the literature [2,3,4]. Due to this scarcity, there is a lack of definitive therapeutic guidelines of IE due to P. mirabilis [1, 2]. Documented treatment of Proteus endocarditis thus far has involved a prolonged course of antibiotics with up to half of patients requiring surgical intervention [5, 6]. Of the existing literature on IE due to Proteus spp., immunologic phenomena have not been frequently reported or well characterized [2]. Therefore, we present a unique case of mitral valve endocarditis caused by PM that highlights the potential role of immunosuppression in this uncommon presentation of IE.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old female with a history of rheumatoid arthritis on chronic prednisone and scheduled Tofacitinib ER 11 mg q daily, factor V Leiden hypercoagulability, prior saddle pulmonary embolism, and no known valvular heart disease presented to the emergency department following a mechanical fall. On admission, she had a complaint of generalized fatigue. She had a temperature of 36.7 °C, heart rate (HR) of 97 beats per minute and a blood pressure (BP) of 155/86 with a normal lactate level. Her lungs were clear and there was no appreciable heart murmur noted. The remainder of the physical exam was normal.

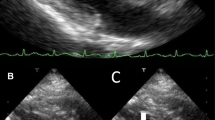

Her white blood cell count was 11,370/µL. Within 1 day of admission, patient had temperature of 40 °C, HR 104 bpm, BP dropping to 103/67 mmHg and white blood cell count increased to 18,480/µL. An abdominal/pelvic CT scan showed evidence of acute/subacute splenic emboli, with wedge-shaped zones of hypoattenuation in the inferior and superior aspects of the spleen (Fig. 1) and a 4 mm ureteral stone without hydronephrosis. Her urinalysis had bacteria, nitrite, and leukocyte esterase with only 5 WBCs. She was admitted to the general medical floor with a diagnosis of cUTI and was started on piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g every 8 h as an extended infusion. A transthoracic echocardiography revealed a 1.2 × 0.5 cm mobile echogenic density on the anterior leaflet of the MV (Fig. 2) with moderate mitral regurgitation (Fig. 3). Urine and blood cultures collected on the day of admission grew a pan sensitive strain of P. mirabilis (Table 1). Antibiotics were changed to ceftriaxone (2 g IV every 24 h) and gentamicin 5 mg/kg/day divided q 8 h. On hospital day 3, the patient developed respiratory distress and hypoxemia due to acute pulmonary edema on CXR (Fig. 4) requiring non-invasive positive pressure ventilation and was transferred to the intensive care unit. She became hypotensive and required intravenous nor-epinephrine. She developed new onset atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response. Follow-up blood cultures continued to grow out P. mirabilis. Her white blood cell count peaked at 41,000 on hospital day 4. She subsequently required a second vasoactive agent, neosynephrine. Repeat echocardiography revealed an enlarging non-mobile vegetation 1.1 × 0.8 cm attached to the atrial side of the anterior MV leaflet. The mitral regurgitation was now severe with flow reversal into the pulmonary veins.

The patient underwent cystoscopy for left ureteral stent placement for the noted stone. She continued to have mixed cardiogenic and septic shock secondary to P. mirabilis. bacteremia and MV endocarditis, now requiring continuous infusions of inotropic and two different vaso-active agents. A pulmonary artery catheter was placed to guide management (Fig. 5). On hospital day 7, she underwent surgical MV replacement with a 29 mm magnaease valve. Intra-op transesophageal echo revealed a well-seeded bioprosthetic mitral valve with no mitral regurgitation.

Repeat blood cultures negative for P. mirabilis. Continuous vasoactive agents and inotropes were tapered to off. Cardiac valve pathology confirmed acute MV endocarditis and intraoperative (Fig. 6). Ceftriaxone (2 g IV every 24 h) was given for 6 weeks post procedure and gentamicin was discontinued. The patient was discharged home post op day 5.

Discussion and conclusions

Proteus mirabilis is Gram negative rod-shaped bacterium, member of the order Enterobacteriales, family Enterobacteriaceae, remains to be one of the common causes for complicated urinary tract infections consisting of flagellae and swarm cell differentiation contributing to its ability to cause ascending UTI and bacteremia. P. mirabilis is known to be producing urease, making urine alkaline from conversion of urea to ammonia and subsequently ammonium by consuming free hydrogen ion. Alkaline urine, in turn, facilitates struvite stones formation consisting of phosphate, carbonate and magnesium and subsequent vicious cycle of leukocytes, struvite, proteinaceous matrix & bacteria forms nidus for infection as infected staghorn calculus [7,8,9,10,11].

Cases of P. mirabilis endocarditis has rarely been reported in the current literature, with only 16 reports of IE caused by any Proteus species presented with high mortality of 43.8% [2]. In a large study of IE, only 3 out of 2761 (0.1%) definite cases were due to Proteus species [12]. While few cases have been documented, most patients with Proteus endocarditis presented with notably severe disease with high mortality [13,14,15,16]. The most recent incidence of native valve Proteus endocarditis was documented in 2016, in which the patient presented with P. mirabilis endocarditis of the aortic valve and was successfully treated with a dual antibiotic regimen of ceftriaxone and gentamicin [3]. Previously, two cases of Proteus endocarditis of native mitral valves were successfully treated without surgical intervention [17, 18].

Similar to factors found to be associated with non-HACEK Gram-negative bacillus (GNB) endocarditis, endocarditis due to enteric bacilli other than Salmonellae, and other previously reported cases of Proteus endocarditis, our patient presented with urinary tract infection (UTI) [3, 13, 19]. In a recent systematic review of Proteus endocarditis, 43.8% of patients had cocontaminant UTI [2]. Therefore, in retrospect, Proteus urosepsis was likely due to a 4 mm ureteral stone in our patient.

Interestingly, while embolic phenomena were frequently reported in cases of Proteus IE, only one other case reported splenic infarctions similarly seen in our patient [2, 18, 20]. Additionally, only 2 out of 14 (14.3%) documented cases of endocarditis due to any Proteus species reported immunologic involvement [2]. We hypothesize that our patient’s immunocompromised status following steroid and Janus Kinase inhibitor usage for rheumatoid arthritis contributed to Gram-negative bacteremia following Proteus urinary tract infection, ultimately seeding the native MV. Additional studies with larger numbers of Proteus endocarditis cases are needed to investigate an association between immunosuppression and P. mirabilis endocarditis. Overall, we summarize a case of P. mirabilis cUTI accentuating into persistent bacteremia and IE due to immunocompromised status of the host and yet being successfully managed by early surgical intervention and extended single antibiotic regimen.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included within this published article.

Abbreviations

- IE:

-

Infective endocarditis

- cUTI:

-

Complicated urinary tract infection

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- TTE:

-

Transthoracic echocardiography

- MV:

-

Mitral valve

- GNB:

-

Gram-negative bacteria

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

References

Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. American Heart Association Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Stroke Council. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:1435–1486. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296.

Ioannou P, Vougiouklakis G. Infective endocarditis by Proteus species: a systematic review. Germs. 2020;10(4):229–39. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2020.1209.

Brotzki CR, Mergenhagen KA, Bulman ZP, Tsuji BT, Berenson CS. Native valve Proteus mirabilis endocarditis: successful treatment of a rare entity formulated by in vitro synergy antibiotic testing. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215956. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-215956.

Albuquerque I, Silva AR, Carreira MS, Friões F. Proteus mirabilis endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12: e230575. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2019-230575.

Habib G, France C, Grazia M, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3075–128. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319.

Goel R, Sekar B, Payne MN. Proteus endocarditis in an intravenous drug user. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015212447.

Griffith DP, Musher DM. Urease: the primary cause of infection-induced urinary stones. Invest Urol. 1976;13(5):346–50.

Chen CY, Chen YH, Lu PL, Lin WR, Chen TC, Lin CY. Proteus mirabilis urinary tract infection and bacteremia: risk factors, clinical presentation, and outcomes. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:228–36.

Schaffer JN, Pearson MM. Proteus mirabilis and urinary tract infections. Microbiol Spectr. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0017-2013.

Prywer J, Olszynski M. Bacterially induced formation of infectious urinary stones: recent developments and future challenges. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(3):292–311.

Allison C, Coleman N, Jones PL, Hughes C. Ability of Proteus mirabilis to invade human urothelial cells is coupled to motility and swarming differentiation. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4740–6.

Morpeth S, Murdoch D, Cabell CH, et al. International Collaboration on Endocarditis Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS) Investigators. Non-hacek Gram-negative bacillus endocarditis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:829–35.

Carruthers MM. Endocarditis due to enteric bacilli other than Salmonellae: case reports and literature review. Am J Med Sci. 1977;273(2):203–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-197703000-00011.

Ananthasubramaniam K, Karthikeyan V. Aortic ring abscess and aortoatrial fistula complicating fulminant prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Proteus mirabilis. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:63–6.

Rosen P, Armstrong D. Infective endocarditis in patients treated for malignant neoplastic diseases: a post mortem study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1973;60:241–50.

Taniguchi T, Murphy FD. Mural bacterial endocarditis produced by Proteus. J Am Med Assoc. 1950;143:427–8.

Claassen DO, Batsis JA, Orenstein R. Proteus mirabilis: a rare cause of infectious endocarditis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39(4):373–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365540600981652.

Kalra A, Cooley C, Tsigrelis C. Treatment of endocarditis due to Proteus species: a literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(4):e222–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2010.12.002.

Falcone M, Tiseo G, Durante-Mangoni E, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of endocarditis due to non-HACEK Gram-negative bacilli: data from the prospective multicenter Italian endocarditis study cohort. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(4):e02208-e2217. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02208-17.

Vandenbos F, Hyvernat H, Lucas P, et al. Enterobacterial native valve endocarditis in the intensive care unit: report of two cases. Revue de Médecine Interne. 2000;21:560–1.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LGG, JMS, DSG, AH, MM, and KBS contributed to the case study concept. Literature review and data collection were performed by LGG, KBS and JMS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LGG and JMS, DSG, AH, MM, and KBS commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The participant has provided informed written consent to the submission of the case report to the journal, including clinical details and images.

Competing interests

Author(s) reports no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Grossman, L.G., Sharkey, J.M., Grossman, D.S. et al. Rare case of Proteus mirabilis native mitral valve endocarditis in an immunocompromised patient. BMC Infect Dis 21, 1250 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06931-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06931-w