Abstract

Background

An upper abdominal mass without tenderness often indicates a benign or malignant tumor once liver or spleen hyperplasia has been excluded. A lymphadenopathic mass from Talaromyces marneffei infection is rare.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 29-year-old human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected man who presented with an upper abdominal mass and without any symptoms related with infection. Histopathology and next-generation sequencing (NGS) following biopsy of the mass confirmed T. marneffei-infected lymphadenopathy, and the patient was successfully treated with amphotericin B and itraconazole.

Conclusions

This case report suggests that potential fungal infection should be considered during the diagnostic workup of a mass in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Upper abdominal distension, along with a non-tender mass, often suggests a benign or malignant tumor once liver or spleen hyperplasia has been excluded. A series of imaging and pathologic examinations are often required to diagnose the mass. However, an upper abdominal mass due to fungal lymphadenopathy is rare. Talaromycosis caused by Talaromyces marneffei is a regional fungal disease that is endemic to Southeast Asia, India, and southern China [1, 2]. Talaromycosis is a life-threatening mycosis that primarily affects immunocompromised individuals and it is common in people living with HIV and is more likely to spread through the blood and affect the whole body [1]. As one of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining diseases, the mortality and morbidity rates of talaromycosis are preceded only by HIV-related tuberculosis and cryptococcosis in Thailand [3]. Although the incidence of talaromycosis in people living with HIV has decreased because of the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy, its mortality is still as high as 20% [4]. The infection usually starts as a subacute disease: patients commonly develop fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and abnormal symptoms of respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases [5]. Skin bumps with a small dent in the center are a common manifestation, in addition to fever and other infection-related presentations [6]. Herein, we describe the diagnostic workup for a patient with an upper abdominal mass derived from T. marneffei-infected lymphadenopathy.

Case presentation

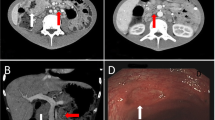

A 29-year-old man presented with abdominal distension, which had lasted for more than 2 months, accompanied by a weight loss of 10 kg. No complaints of chills and fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or diarrhea were reported by this patient. Physical examination revealed a swollen abdomen with a mass of 10 cm in diameter in the upper abdomen and multiple swollen lymph nodes in the neck. HIV antibody test was positive, and HIV-1 infection was confirmed with only 8 CD4+ cells/μL. Laboratory tests revealed that he had anemia and leukopenia, in addition to elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels (Table 1). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a giant mass in the upper abdomen (Fig. 1a). Based on the clinical and imaging findings, lymphoma was suspected. Subsequently, a cervical lymph node biopsy was performed, which demonstrated large areas of tissue necrosis in the lymph nodes, along with a large number of foam cell reactions around them as well as numerous yeast-like cells in the cytoplasm, suggesting a fungal infection (Fig. 2). The T. marneffei infection was initially diagnosed by NGS of the retroperitoneal lymph node tissue, which revealed a T. marneffei fungemia of 39,185 unique reads with 96.42% coverage of identified fungal genes in 72 h (Fig. 3). The blood and tissue culture grew T. marneffei in 11 and 5 days, respectively, confirming the diagnosis of T. marneffei infection.

Hematoxylin–eosin staining (a magnification, ×400), Gomori methenamine silver staining (b magnification, ×400), and periodic acid schiff staining (c magnification, ×400), show large areas of soft tissue necrosis in the cervical lymph nodes accompanied with a large number of foam cell reactions around them, along with multiple yeast-like cells gathered in the cytoplasm, suggesting a fungal infection

NGS coverage map of tissue from the retroperitoneal lymph nodes suggested that T. marneffei was the main pathogen, and a total coverage of 9.37% was obtained (a). Distribution of viruses, bacteria, and fungi identified in the retroperitoneal lymph node tissue by NGS revealed that T. marneffei was the main pathogen, with a sequence number of 39,182 and highest relative abundance of 96.42% (b)

After the diagnosis was considered to be a fungal infection following neck lymph node biopsy, treatment with intravenous amphotericin B was initiated. When the diagnosis of T. marneffei was confirmed by NGS, the current treatment was continued. After 2 weeks, oral itraconazole for consolidation therapy along with antiretroviral therapy was started, resulting in a favorable clinical response in 1 month and shrinkage of the abdominal mass (Fig. 1b). The patient was discharged from the hospital in a stable condition.

Discussion and conclusions

Lymphadenopathy is extremely common in patients with HIV infection and has several possible causes, including the generalized lymphadenopathy of HIV-infection, malignancy, and single or multiple co-infections [7]. As with the case that we reported, HIV-infected person with abdominal lymphadenopathy as the main clinical symptom may be finally diagnosed with T. marneffei infection. T. marneffei can cause infection in immunocompromised individuals with, or without, a history of residence in, or travel to, an endemic region [8]. It is the most important thermally dimorphic fungus, which can cause respiratory, skin, and systemic mycosis in China and Southeast Asia [9]; it is also a life-threatening mycosis that primarily affects immunocompromised individuals [1]. The main risk factor for T. marneffei infection is cell-mediated immune dysfunction, which is usually secondary to HIV infection, especially in people with CD4+ cell counts below 100 cells/μL [10]. The symptoms of T. marneffei infection vary. The most common symptoms include fever, weight loss, malaise and anemia. There may also be fungemia, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, lung disease (non-productive cough and dyspnea), diarrhea, splenomegaly, and systemic skin lesions [11]. Skin lesions are present in 60–70% of patients, which are often the early manifestations of disseminated cases, and more common on the face, trunk and upper limbs [6]. The common laboratory findings of T. marneffei infection include anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated transaminases [12]. The laboratory examination results of the patient we reported suggest anemia and leukopenia in addition to elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin levels. These were helpful in making the early diagnosis of T. marneffei infection.

Microscopic findings of intramacrophage and extramacrophage yeast organisms in smears of skin lesions, lymph nodes, and bone marrow aspirate can lead to a rapid presumptive diagnosis [6]. In addition, T. marneffei is a dimorphic fungus, and a diffusible red pigment that can be seen on culture can confirm the diagnosis. However, the very long time for culture, can lead to delays in diagnosis and increased mortality, especially in patients without skin lesions [8]. The histopathologic finding of intracellular and extracellular yeast forms and the characteristic cross-septation of T. marneffei highlighted by Gomori methenamine silver staining from specimens obtained from the affected tissue or T. marneffei grew in cultures that could identified the diagnosis [13]. In atypical and severe cases, it is difficult to establish a rapid diagnosis using traditional assays. The patient whose case we reported, was characterized mainly with an abdominal mass, but without the typical T. marneffei symptoms, such as skin lesions. Finally, the nucleotide sequence of T. marneffei in the abdominal mass samples from our patient, was identified quickly by NGS. It can be seen that NGS testing brings the dawn of diagnosis detect rare pathogen and takes a shorter time [14]. Actually, The current gold standard for the diagnosis of T. marneffei infection is pathogen culture, but culture generally takes 7–10 days, making early diagnosis difficult. In contrast, NGS diagnosis only takes 24–72 h [15].

Antifungal therapy is the first choice of treatment for T. marneffei, and it is classified into induction, consolidation, and maintenance stages. International guidelines recommend the use of amphotericin B deoxycholate for initial (induction) treatment at a dose of 0.7 to 1 mg per kilogram of body weight per day for 2 weeks, followed by itraconazole at a daily dose of 400 mg for 10 weeks [16]. A recent randomized controlled trial on itraconazole versus amphotericin B in the treatment of penicilliosis in Vietnam suggests that amphotericin B is superior to itraconazole at induction stage in HIV related T. marneffei infection [17].

Unlike previously reported cases, we reported an unusual case of T. marneffei infection in a patient with AIDS, the principal clinical manifestations of abdominal distension and abdominal mass. Due to the lack of specific clinical manifestations, T. marneffei infection could likely be misdiagnosed as tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and lymphoma in patients with systemic lymphadenopathy. Accordingly, it is necessary to emphasize the need to diagnose this disease. In the case of atypical talaromycosis, the diagnosis is more rapid by NGS than by biopsy or culture, allowing rapid initiation of therapy, which is particularly important in immunocompromised patients. Hence, rapid diagnosis is of significant benefit to these patients.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

References

Vanittanakom N, Cooper C, Fisher M, Sirisanthana T. Penicillium marneffei infection and recent advances in the epidemiology and molecular biology aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(1):95–110.

Hu Y, Zhang J, Li X, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Ma J, Xi L. Penicillium marneffei infection: an emerging disease in mainland China. Mycopathologia. 2013;175:57–67.

Sirisanthana T, Supparatpinyo K, Perriens J, Nelson K. Amphotericin B and itraconazole for treatment of disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(5):1107–10.

Wang Y, Xu H, Han Z, Zeng L, Liang C, Chen X, Chen Y, Cai J, Hao W, Chan J, et al. Serological surveillance for Penicillium marneffei infection in HIV-infected patients during 2004–2011 in Guangzhou, China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(5):484–9.

Si Z, Qiao J. Talaromyces marneffei infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2580.

Limper AH, Adenis A, Le T, Harrison TS. Fungal infections in HIV/AIDS. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(11):e334–43.

Mudd J, Murphy P, Manion M, Debernardo R, Hardacre J, Ammori J, Hardy G, Harding C, Mahabaleshwar G, Jain M, et al. Impaired T-cell responses to sphingosine-1-phosphate in HIV-1 infected lymph nodes. Blood. 2013;121(15):2914–22.

Le T, Wolbers M, Chi NH, Quang VM, Chinh NT, Lan NP, Lam PS, Kozal MJ, Shikuma CM, Day JN, et al. Epidemiology, seasonality, and predictors of outcome of AIDS-associated Penicillium marneffei infection in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(7):945–52.

Supparatpinyo K, Khamwan C, Baosoung V, Nelson K, Sirisanthana T. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in southeast Asia. Lancet (London, England). 1994;344(8915):110–3.

Chan JF, Lau SK, Yuen KY, Woo PC. Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei infection in non-HIV-infected patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e19.

Wong S, Wong K. Penicillium marneffei infection in AIDS. Pathol Res Int. 2011;2011:764293.

Larsson M, Nguyen L, Wertheim H, Dao T, Taylor W, Horby P, Nguyen T, Nguyen M, Le T, Nguyen K. Clinical characteristics and outcome of Penicillium marneffei infection among HIV-infected patients in northern Vietnam. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9(1):24.

Chen D, Chang C, Chen M, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Zhang T, Wang Z, Yan J, Zhu H, Zheng L, et al. Unusual disseminated Talaromyces marneffei infection mimicking lymphoma in a non-immunosuppressed patient in East China: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):800.

Church D, Cerutti L, Gürtler A, Griener T, Zelazny A, Emler S. Performance and application of 16S rRNA gene cycle sequencing for routine identification of bacteria in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;33(4):e00053-19.

Chen P, Sun W, He Y. Comparison of the next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology with culture methods in the diagnosis of bacterial and fungal infections. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(9):4924–9.

Kaplan JEBC, Holmes KK, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-54):51–207.

Le T, Kinh N, Cuc N, Tung N, Lam N, Thuy P, Cuong D, Phuc P, Vinh V, Hanh D, et al. A trial of itraconazole or amphotericin B for HIV-associated talaromycosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2329–40.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the patient for the support given in providing the data.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant numbers 81873761 and 81672026]; National Science and Technology Major Special Program of the 13th Five-Year Plan of China [Grant numbers 2018ZX10302104 and 2018ZX10302205]. The funders play a role in study design, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data, and they study supervision and providing important intellectual content.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XC: Study conception and design; drafting of manuscript; review, analysis and interpretation of scientific literature. LJ: critical revision of the manuscript and analysis of the analysis of NGS data and production of sequencing coverage map; YW: acquisition clinical data; JC: performing the pathological diagnosis and analyzing the result of the pathological examination; TZ and YM: providing important intellectual content; YZ: study conception and design, obtaining funding and study supervision. All authors have contributed to the manuscript and ensure that this is the case. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing You An Hospital, Capital Medical University.

Consent to publish

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Jia, L., Wu, Y. et al. A mass in the upper abdomen derived from Talaromyces marneffei infected lymphadenopathy: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 21, 750 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06489-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06489-7