Abstract

Background

This antimicrobial surveillance study reports in vitro antimicrobial activity and susceptibility data for a panel of agents against respiratory isolates of Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Methods

Isolates from respiratory specimens were collected in Africa/Middle East, Asia/South Pacific, Europe and Latin America between 2016 and 2018, as part of the Antimicrobial Testing Leadership and Surveillance (ATLAS) program. Broth microdilution methodology was used to quantify minimum inhibitory concentrations, from which rates of susceptibility were determined using EUCAST breakpoints (version 10). Rates of subsets with genes encoding β-lactamases (extended-spectrum β-lactamases [ESBLs], serine carbapenemases and metallo-β-lactamases [MBLs]) were also determined, as well as rates of multidrug-resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa.

Results

Among all respiratory Enterobacterales isolates, susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenem, colistin and amikacin was ≥94.4% in each region. For Enterobacterales isolates that were ESBL-positive or carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative, ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility was 93.6 and 98.9%, respectively. Fewer than 42.7% of MBL-positive Enterobacterales isolates were susceptible to any agents, except colistin (89.0% susceptible). Tigecycline susceptibility was ≥90.0% among Citrobacter koseri and Escherichia coli isolates, including all β-lactamase-positive subsets. ESBL-positive Enterobacterales were more commonly identified in each region than isolates that were ESBL/carbapenemase-positive; carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative; or MBL-positive. Among all respiratory P. aeruginosa isolates, the combined susceptibility rates (susceptible at standard dosing regimen plus susceptible at increased exposure) were highest to ceftazidime-avibactam, colistin and amikacin (≥82.4% in each region). Susceptibility to colistin was ≥98.1% for all β-lactamase-positive subsets of P. aeruginosa. The lowest rates of antimicrobial susceptibility were observed among MBL-positive isolates of P. aeruginosa (≤56.6%), with the exception of colistin (100% susceptible). MDR P. aeruginosa were most frequently identified in each region (18.7–28.7%), compared with the subsets of ESBL-positive; carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative; or MBL-positive isolates.

Conclusions

Rates of susceptibility among the collections of respiratory Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa isolates were highest to ceftazidime-avibactam, colistin and amikacin in each region. Tigecycline was active against all subsets of C. koseri and E. coli, and colistin was active against all subsets of P. aeruginosa. The findings of this study indicate the need for continued antimicrobial surveillance among respiratory Gram-negative pathogens, in particular those with genes encoding MBLs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacteria is a long-standing problem that needs to be monitored in an effort to preserve the efficacy of current antimicrobial agents. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and species of Enterobacterales are common causative pathogens of respiratory infections such as hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (HABP) and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (VABP), and respiratory infections caused by antimicrobial-resistant Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa are associated with higher patient mortality [1, 2]. Among isolates of Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa, antimicrobial resistance can be mediated by the production of β-lactamases, for example, extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), serine carbapenemases and metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) [3].

Ceftazidime-avibactam is a combination antimicrobial agent comprising ceftazidime, a third-generation cephalosporin, and avibactam, a non-β-lactam β-lactamase-inhibitor. Avibactam inhibits Ambler class A, class C, and certain class D OXA-type β-lactamases, but not MBLs. Therefore ceftazidime-avibactam is active against ESBL- and serine carbapenemase-positive Gram-negative isolates, but not against MBL-positive isolates [4,5,6]. Ceftazidime-avibactam has been approved for the treatment of HABP and VABP, as well as complicated intra-abdominal infection (in combination with metronidazole) and complicated urinary tract infection (including pyelonephritis) [7, 8]. In Europe, ceftazidime-avibactam is also indicated for the treatment of infections due to aerobic Gram-negative organisms in adult patients with limited treatment options [8].

The aim of this study is to report in vitro antimicrobial activity and susceptibility data for a panel of antimicrobial agents against isolates of Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa collected from respiratory specimens as part of the Antimicrobial Testing Leadership and Surveillance (ATLAS) program (2016–2018). Data on rates of resistant isolates will also be presented. The geographical regions of collection included in the analysis are Africa/Middle East, Asia/South Pacific, Europe and Latin America.

Methods

Isolates from respiratory specimens were collected from hospitalised patients from participating study centers between 2016 and 2018 in four geographical regions (Africa/Middle East, Asia/South Pacific, Europe and Latin America). Only non-duplicate isolates of the organism considered to be the potential causative pathogen of the infection were included in the study. Demographic information recorded for each isolate included specimen source, patient age and sex, and type of hospital setting.

Isolates were collected and identified at the participating center, and pure cultures were shipped to the central laboratory (International Health Management Associates [IHMA] Inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA). The central laboratory then re-identified and confirmed bacterial species using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Bruker Biotyper; Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA), and performed antimicrobial susceptibility testing using self-manufactured frozen broth microdilution panels [9]. Ceftazidime-avibactam was tested with a fixed concentration of 4 mg/L avibactam with doubling dilutions of ceftazidime. All minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were interpreted using version 10.0 of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) clinical breakpoint tables [10]. Among the Enterobacterales, isolates of Morganella spp., Proteus spp., Providencia spp. or Serratia spp. were excluded from the analysis for colistin activity, due to intrinsic resistance. All isolates of Enterobacterales were included in the analysis for tigecycline activity, but tigecycline EUCAST breakpoints are only available for isolates of Citrobacter koseri and Escherichia coli. For isolates of P. aeruginosa, EUCAST have revised the susceptible breakpoints at the standard dosing regimen (S) for piperacillin-tazobactam, aztreonam, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem and levofloxacin [10], therefore isolates tested against these antimicrobial agents are categorized as either susceptible at increased exposure (I), or as resistant (R). For all antimicrobial agents tested against P. aeruginosa, the combined susceptibility rates (susceptible at standard dosing regimen plus susceptible at increased exposure) are presented here.

A multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype among isolates of P. aeruginosa was defined as resistance to one or more antimicrobial agent (given in parentheses) from three or more of the following antimicrobial classes: aminoglycosides (amikacin), carbapenems (imipenem or meropenem), cephalosporins (ceftazidime or cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin) and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (piperacillin-tazobactam).

Enterobacterales isolates with MIC values of ≥2 mg/L to meropenem were screened for genes encoding clinically-relevant β-lactamases (ESBLs: SHV, TEM, CTX-M, VEB, PER and GES; plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases: ACC, ACT, CMY, DHA, FOX, MIR and MOX; serine carbapenemases: GES, KPC and OXA-48-like; and MBLs: NDM, IMP, VIM, SPM and GIM) using published multiplex PCR assays [11]. Additionally, isolates of E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca and Proteus mirabilis with MIC values of ≥2 mg/L to ceftazidime or aztreonam were screened for the same genes. P. aeruginosa isolates with meropenem MIC values of ≥4 mg/L were screened for genes encoding MBLs (IMP, VIM, NDM, GIM and SPM) and serine carbapenemases (KPC and GES) using published multiplex PCR assays [12]. All detected carbapenemase genes were amplified using flanking primers and sequenced, and sequences were compared against publicly available databases.

The following subsets of resistant isolates are presented: ESBL-positive Enterobacterales; ESBL-positive and carbapenemase-positive Enterobacterales (hereafter described as ESBL/carbapenemase-positive); carbapenemase-positive and MBL-negative Enterobacterales or P. aeruginosa; carbapenemase-positive and MBL-positive Enterobacterales or P. aeruginosa (hereafter described as MBL-positive) and MDR P. aeruginosa.

Results

Isolates collected

A total of 15,460 isolates from respiratory specimens (10,128 Enterobacterales and 5332 P. aeruginosa) were collected from a total of 51 countries in four geographical regions between 2016 and 2018. The number of centers in each participating country and the number of isolates collected by each center are presented in Supplementary Table 1. More than half of isolates were collected in Europe (58.6%; n = 9055), followed by Asia/South Pacific (19.7%; n = 3040); Latin America (13.3%; n = 2061) and Africa/Middle East (8.4%; n = 1304).

Respiratory specimen sources were: sputum, 45.8% (n = 7088); endotracheal aspirate, 27.1% (n = 4190); bronchoalveolar lavage, 13.9% (n = 2146); bronchus, 8.2% (n = 1269). Less than 3% of isolates were classified as unspecified, thoracentesis fluid, lungs, trachea or aspirate.

The majority of isolates from respiratory specimens were collected from male patients (64.5%; n = 9972) and half were from patients aged 65 years and older (50.0%; n = 7723). The percentage of isolates collected from respiratory specimens on general wards (47.9%; n = 7398) was similar to intensive care units (43.4%; n = 6716).

Enterobacterales

Antimicrobial activity and susceptibility data for a panel of antimicrobial agents against the collection of Enterobacterales isolates from respiratory sources are shown by region in Table 1. In each region, the highest rates of susceptibility among the collection of Enterobacterales were to ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenem, colistin and amikacin (≥94.4%). Tigecycline susceptibility in all regions was ≥97.9% among isolates of C. koseri and E. coli, the only species within the Enterobacterales collection to which EUCAST breakpoints apply.

Among ESBL-positive Enterobacterales, susceptibility was highest to ceftazidime-avibactam and colistin (≥93.6%) (Table 2). Susceptibility to tigecycline was high among ESBL-positive C. koseri and E. coli (98.8%). The susceptibility among ESBL/carbapenemase-positive Enterobacterales was highest to colistin and ceftazidime-avibactam (≥64.7%). In this subset, 92.9% of C. koseri and E. coli were susceptible to tigecycline. Among carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative Enterobacterales, susceptibility was highest to ceftazidime-avibactam and colistin (≥74.1%). All carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative C. koseri and E. coli were susceptible to tigecycline. For MBL-positive Enterobacterales, susceptibility was highest to colistin, and the susceptibility of MBL-positive C. koseri and E. coli to tigecycline was 90.0%. No isolates of MBL-positive Enterobacterales were susceptible to amoxicillin-clavulanate, ceftazidime, ceftazidime-avibactam or cefepime.

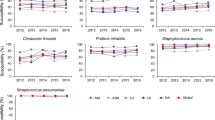

By region, the 2016–2018 rate of ESBL-positive Enterobacterales was lowest in Europe and highest in Africa/Middle East (Fig. 1). Fewer than 5% of Enterobacterales isolates collected in each region were ESBL/carbapenemase-positive, carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative or MBL-positive.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Antimicrobial activity and susceptibility data for a panel of antimicrobial agents against the collection of P. aeruginosa isolates from respiratory sources are shown by region in Table 3. The combined susceptibility (susceptible at standard dosing regimen plus susceptible at increased exposure) among the collection of P. aeruginosa in each region was highest to colistin, ceftazidime-avibactam and amikacin (≥82.4%). Rates of susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenem and amikacin were lower in Latin America than in Africa/Middle East, Asia/South Pacific and Europe.

Among MDR isolates of P. aeruginosa, susceptibility was highest to colistin, ceftazidime-avibactam and amikacin (≥61.3%) (Table 4). Susceptibility among carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative P. aeruginosa was highest to colistin and ceftazidime-avibactam (≥71.7%). No isolates of carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative P. aeruginosa were susceptible to imipenem. All MBL-positive P. aeruginosa isolates were susceptible to colistin, with ≤19.1% susceptible to amikacin or ceftazidime-avibactam.

By region, the 2016–2018 rate of MDR P. aeruginosa was lowest in Asia/South Pacific and highest in Latin America (Fig. 2). The 2016–2018 rate of carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative P. aeruginosa in each region was ≤3%, with only one such isolate collected in Africa/Middle East and three isolates in Asia/South Pacific. The 2016–2018 rate of MBL-positive P. aeruginosa was lowest in Asia/South Pacific and highest in Latin America.

Discussion

This study presents in vitro antimicrobial activity and susceptibility data for a panel of antimicrobial agents against respiratory isolates of Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa, collected as part of the ATLAS program (2016–2018), as well as data on subsets of resistant isolates.

Among the Enterobacterales isolates, rates of antimicrobial susceptibility to amikacin, ceftazidime-avibactam, colistin, meropenem and tigecycline were similar, irrespective of the geographical region of collection. For P. aeruginosa isolates, however, rates of susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam, colistin and amikacin were lower in Latin America, when compared with the other regions. In a phase 3 trial of hospitalized adults with HABP or VABP due to Gram-negative pathogens, the overall ceftazidime-avibactam MIC90 against isolates of Enterobacterales (n = 317) was 0.5 mg/L, and against isolates of P. aeruginosa (n = 101) was 8 mg/L [13]. These data are comparable with the MIC90 values for ceftazidime-avibactam in the current study, with the exception of isolates from Latin America, where the ceftazidime-avibactam MIC90 against the collection of P. aeruginosa was 32 mg/L.

The rates of all subsets of resistant P. aeruginosa isolates presented here were higher in Latin America than the other regions, which may explain the lower ceftazidime-avibactam activity and susceptibility seen in Latin America. The rate of MDR P. aeruginosa in Latin America (28.7%) was similar to a 2015–2016 global antimicrobial surveillance study (34.6%), where the rate in Latin America was the highest among seven geographical regions [14]. The 2015–2016 global study included aztreonam and colistin in their MDR study definition [14], whereas the current study definition of MDR P. aeruginosa omitted aztreonam and colistin, based on guidance from the Belgian High Council of Health [15] and the combinations of pathogens and antimicrobial agents under continued European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) surveillance [16]. A 2012–2015 study of clinical P. aeruginosa isolates from Latin America reported that 35.8% (643/1794) of P. aeruginosa isolates were meropenem-nonsusceptible (% intermediate plus % resistant) [17]; similar to the current study (37.0% [298/805]).

In the present study, susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam among carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative Enterobacterales isolates remained high (98.9%). This was comparable to the 2012–2015 rate of ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility reported among isolates of Enterobacterales, collected from the same regions as the current study, that were OXA-48-positive and MBL-negative (99.2%) [6]. The lack of ceftazidime-avibactam activity against MBL-positive isolates (due to the hydrolysis of both ceftazidime and avibactam by the MBL class of β-lactamases [18]) is clearly demonstrated in the present study. In addition, ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility was notably lower among ESBL/carbapenemase-positive Enterobacterales (64.7%), compared with ESBL-positive isolates (93.6%). A total of 124 isolates in the ESBL/carbapenemase-positive subset were ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant, of which 123 were MBL-positive and the remaining isolate was carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative (data not shown). The single carbapenemase-positive/MBL-negative isolate had a ceftazidime-avibactam MIC of 32 mg/L (EUCAST resistance breakpoint, > 8 mg/L). Isolates of Enterobacterales have been found to coproduce MBLs and Ambler class A β-lactamases, such as ESBLs [19].

The limitations of this study were the predefined number of isolates per species, as well as the variability in center and country participation between the study years, meaning that these results cannot be interpreted as epidemiology findings. The details on the type or size of study centers are not recorded at the time of isolate collection, which could limit the clinical relevance of the data. Despite this, the data reported here highlight the presence of antimicrobial-resistant respiratory Gram-negative pathogens in the four geographical regions presented. Ceftazidime-avibactam was active against resistant isolates of Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa, with the exception of those organisms that were MBL-positive; among this subset of Enterobacterales, susceptibility was highest to colistin. This study provides valuable information to clinicians on the susceptibility of these resistant isolates to antimicrobial agents in current use. Continued monitoring of the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of respiratory Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa isolates is necessary to identify the most difficult-to-treat respiratory pathogens and improve patient outcomes.

Conclusions

Among the collection of respiratory Enterobacterales isolates, rates of susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenem, colistin and amikacin were 94.4–99.6% in each region. For the subsets of resistant Enterobacterales, rates of susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenem and amikacin were lowest among MBL-positive isolates of Enterobacterales (0.0–42.7%), whereas colistin susceptibility was 89.0%. At least 90.0% of all Citrobacter koseri and Escherichia coli isolates were susceptible to tigecycline, including all subsets of resistant isolates.

For the collection of respiratory P. aeruginosa isolates, ceftazidime-avibactam, colistin and amikacin susceptibility was 82.4–99.8%. Among all resistant isolates of P. aeruginosa, colistin susceptibility remained ≥98.1%. For MBL-positive P. aeruginosa, antimicrobial susceptibility was lowest to all agents except colistin and aztreonam (0.0–19.1%).

For the majority of agents, antimicrobial susceptibility was reduced among the subsets of resistant Gram-negative isolates; most notably the MBL-positive subset. Monitoring of antimicrobial susceptibility is therefore necessary to help physicians to choose appropriate treatment options and improve the treatment outcomes for respiratory Gram-negative infections.

Availability of data and materials

Data from the study can be accessed at https://atlas-surveillance.com. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study of isolates from respiratory specimens collected in Africa/Middle East, Asia/South Pacific, Europe and Latin America between 2016 and 2018, as part of the ATLAS program, are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ATLAS:

-

Antimicrobial Testing Leadership and Surveillance

- ESBL:

-

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase

- EUCAST:

-

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- HABP:

-

Hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia

- I:

-

Susceptible, increased exposure

- KPC:

-

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase

- MBL:

-

Metallo-β-lactamase

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistant

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration (mg/L)

- MIC50 :

-

MIC required to inhibit growth of 50% of isolates (mg/L)

- MIC90 :

-

MIC required to inhibit growth of 90% of isolates (mg/L)

- N/A:

-

Not available

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- R:

-

Resistant

- S:

-

Susceptible (standard dosing)

- VABP:

-

Ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia

References

Zilberberg MD, Nathanson BH, Sulham K, Fan W, Shorr AF. A novel algorithm to analyze epidemiology and outcomes of carbapenem resistance among patients with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: a retrospective cohort study. Chest. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2018.12.024.

Watkins RR, Van Duin D. Current trends in the treatment of pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. F1000Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16517.2.

Bush K. Past and present perspectives on β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(10). https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01076-18.

Zhanel GG, Lawson CD, Adam H, Schweizer F, Zelenitsky S, Lagacé-Wiens PR, et al. Ceftazidime-avibactam: a novel cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor combination. Drugs. 2013;73(2):159–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0013-7.

Lagacé-Wiens P, Walkty A, Karlowsky JA. Ceftazidime-avibactam: an evidence-based review of its pharmacology and potential use in the treatment of gram-negative bacterial infections. Core Evid. 2014. https://doi.org/10.2147/CE.S40698 eCollection 2014.

Kazmierczak KM, Bradford PA, Stone GG, de Jonge BLM, Sahm DF. In vitro activity of ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam-avibactam against OXA-48-carrying Enterobacteriaceae isolated as part of the international network for optimal resistance monitoring (INFORM) global surveillance program from 2012 to 2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(12). https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00592-18.

Allergan (AbbVie). Avycaz (ceftazidime-avibactam) for injection, for intravenous use: prescribing information. Madison: Allergan; 2019. https://www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/avycaz_pi. Accessed 21 August 2020

Pfizer. Zavicefta: summary of product characteristics. Groton: Pfizer. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zavicefta-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 21 August 2020.

International Standards Organization. Clinical laboratory testing and in vitro diagnostic test systems - Susceptibility testing of infectious agents and evaluation of performance of antimicrobial susceptibility test devices. Part 1: Reference method for testing the in vitro activity of antimicrobial agents against rapidly growing aerobic bacteria involved in infectious diseases. 2006. ISO 20776-1.

The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 10.0, 2020. http://www.eucast.org. Accessed 12 August 2020.

Lob SH, Kazmierczak KM, Badal RE, Hackel MA, Bouchillon SK, Biedenbach DJ, et al. Trends in susceptibility of Escherichia coli from intra-abdominal infections to ertapenem and comparators in the United States according to data from the SMART program, 2009 to 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(6):3606–10. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.05186-14.

Nichols WW, de Jonge BL, Kazmierczak KM, Karlowsky JA, Sahm DF. In vitro susceptibility of global surveillance isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to ceftazidime-avibactam (INFORM 2012 to 2014). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(8):4743–9. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00220-16.

Torres A, Zhong N, Pachl J, Timsit JF, Kollef M, Chen Z, et al. Ceftazidime–avibactam versus meropenem in nosocomial pneumonia, including ventilator-associated pneumonia (REPROVE): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):285–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30747-8.

Karlowsky JA, Lob SH, Young K, Motyl MR, Sahm DF. Activity of imipenem/relebactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa with antimicrobial-resistant phenotypes from seven global regions: SMART 2015-2016. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;15:140–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2018.07.012.

Conseil Supérieur de la Santé (CSS). Recommandations en matière de prévention, maîtrise et prise en charge des patients porteurs de bactéries multi-résistantes aux antibiotiques (MDRO) dans les institutions de soins. Bruxelles: CSS; 2019. Avis n° 9277

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) reporting protocol 2020. European antimicrobial resistance surveillance network (EARS-net) surveillance data for 2019. ECDC; 2020.

Karlowsky JA, Kazmierczak KM, Bouchillon SK, de Jonge BLM, Stone GG, Sahm DF. In vitro activity of ceftazidime-avibactam against clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa collected in Latin American countries: results from the INFORM global surveillance program, 2012 to 2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(4). https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01814-18.

Abboud MI, Damblon C, Brem J, Smargiasso N, Mercuri P, Gilbert B, et al. Interaction of avibactam with class B metallo-β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(10):5655–62. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00897-16.

Biedenbach DJ, Kazmierczak K, Bouchillon SK, Sahm DF, Bradford PA. In vitro activity of aztreonam-avibactam against a global collection of gram-negative pathogens from 2012 and 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(7):4239–48. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00206-15.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participating investigators and laboratories and would also like to thank the staff at International Health Management Associates (IHMA) Inc. for their co-ordination of the study.

Funding

This study is funded by Pfizer. Medical writing support was provided by Neera Hobson, PhD at Micron Research Ltd. (Ely, UK), which was funded by Pfizer. Micron Research Ltd. also provided data management services which were funded by Pfizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DP participated in data collection and interpretation, as well as drafting and reviewing the manuscript. GGS was involved in the study design, participated in data interpretation, and drafted and reviewed the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DP received funding for performing collection of clinical bacterial isolates for sending to International Health Management Associates (IHMA) Inc. GGS is an employee and a shareholder of Pfizer Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

. Number of centers and respiratory isolates in participating counties (ATLAS 2016–2018). Supplementary Table 2. Species of respiratory Enterobacterales isolates (n = 10,128) (ATLAS 2016–2018).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Piérard, D., Stone, G.G. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical respiratory isolates to ceftazidime-avibactam and comparators (2016–2018). BMC Infect Dis 21, 600 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06153-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06153-0