Abstract

Background

To investigate the trends and correlation between antibacterial consumption and carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative bacteria from 2012 to 2019 in a tertiary-care teaching hospital in southern China.

Methods

This retrospective study included data from hospital-wide inpatients collected between January 2012 and December 2019. Data on antibacterial consumption were expressed as defined daily doses (DDDs)/1000 patient-days. Antibacterials were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. The trends in antimicrobial usage and resistance were analyzed by linear regression, while Pearson correlation analysis was used for assessing correlations.

Results

An increasing trend in the annual consumption of tetracyclines, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor (BL/BLI) combinations, and carbapenems was observed (P < 0.05). Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) significantly increased (P < 0.05) from 18% in 2012 to 60% in 2019. Moreover, significant positive correlations were found between resistance to carbapenems in A. baumannii (P < 0.05) and Escherichia coli (E. coli; P < 0.05) and consumption of carbapenems, while the resistance rate of A. baumannii to carbapenems was positively correlated with cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor (C/BLI) combinations (P < 0.01) and tetracyclines usage (P < 0.05). We also found that use of quinolones was positively correlated with the resistance rate of Burkholderia cepacia (B. cepacia) to carbapenems (P < 0.05), and increasing uses of carbapenems (P < 0.01) and penicillin/β-Lactamase inhibitor (P/BLI) combinations (P < 0.01) were significantly correlated with reduced resistance of Enterobacter cloacae (E. cloacae) to carbapenems.

Conclusion

These results revealed significant correlations between consumption of antibiotics and carbapenem resistance rates in Gram-negative bacteria. Implementing proper management strategies and reducing the unreasonable use of antibacterial drugs may be an effective measure to reduce the spread of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CRGN), which should be confirmed by further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Increasing antibacterial resistance and associated infections have become a global health threat [1]. Antibacterial resistance can lead to unresponsiveness to treatment, resulting in persistent illness and increased risk of death [2]. Multidrug-resistant organisms harm not only patients who are infected but also those not infected with multidrug-resistant bacteria. All patients are affected by the lack of appropriate antibiotic regimens due to less efficient antimicrobial agents [3].

Among the many antibiotic-resistant bacteria infections, carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CRGN), which mainly include carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA), pose a significant threat to humanity in terms of mortality, medical burden, and trends in antimicrobial resistance [4]. The emergence and spread of CRGN are considered to be mainly related to the hydrolysis of carbapenemase, changes in membrane permeability [5], overuse of antimicrobials, and healthcare-associated infections [6]. In a report, the European Union and European Economic Area estimated that the burden of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia (CRKP) increased the most (by 6.16 times) among the bacterial species studied in terms of the number of infections and deaths during 2007–2015, followed by carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli (CREC) [7]. In the face of rapidly increasing antimicrobial resistance, the World Health Organization (WHO) ranked CRGN as the most urgent bacteria in 2017 [8].

According to data reported by the China Antibacterial Surveillance Network, the usage rate and defined daily doses (DDDs)/1000 patient-days in inpatients have shown a downward trend from 2011 to 2017 since the rectification of the clinical application of antimicrobials in China in 2011 [9]. However, consumption of carbapenems has increased, with a rise of carbapenem resistance rate in Gram-negative bacteria. Therefore, it was proposed to strengthen the management of carbapenems and tigecycline to reduce carbapenem resistance in China in February 2017. It was shown that reduced antibacterial use is positively associated with improved bacterial resistance without negatively affecting medical quality indexes [10]. Since use of antibiotics can create selective pressure favoring the spread of resistance [11], assessing the association of antibiotic usage with antimicrobial resistance could help local physicians and decision-makers make better use of antibacterials and distribute healthcare funds more effectively, while improving infection control strategies [12]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the changing trend of antibacterial usage and the prevalence of CRGN from 2012 to 2019 in a tertiary hospital and to evaluate the correlation between them.

Methods

Study design and setting

The data in this study were collected from local monitoring of carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative bacteria and antibacterial consumption at the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, which is a comprehensive, tertiary care, university-affiliated, and teaching hospital in the south of China. It is also the largest hospital in Southeast Guangxi, with currently 2400 available beds.

Bacterial isolates and susceptibility testing

Antibiotic resistance data, which were provided by the hospital’s clinical microbiology laboratory, were extracted from the hospital information system. A total of 37,716 cases with data on Gram-negative bacterial resistance were recorded, including all positive clinical specimens, and 34,489 cases with data on six isolated species, including A. baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), Klebsiella pneumonia (K. pneumonia), E. coli, E. cloacae, and B. cepacia, which were target bacteria to be monitored in this hospital. The resistance rate was reported as the percentage of resistant isolates among all tested isolates. Antimicrobial susceptibility was tested based on the latest performance standards set by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Tested isolates that had intermediately resistance were eliminated from this analysis. We retained the first isolate of duplicate test results from the same patient during the same in-patient stay. The isolation rate was calculated as the percentage of total gram-negative bacterial isolates.

Antibacterial consumption

Antibacterial consumption data from 2012 to 2019 were obtained from the hospital information system. According to the Guidelines for Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification and DDD assignment 23rd edition (2020, [13]), which was developed by the WHO, data on antibacterial consumption were expressed as DDDs/1000 patient-days. Antibacterials were classified according to the ATC classification system.

Statistical analysis

The changing trends of antimicrobial use and resistance were analyzed by linear regression. Pearson correlation analysis was used for evaluating the relationship between antibiotic consumption and bacterial resistance rates. SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, USA) was used for statistical analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Antibacterial consumption

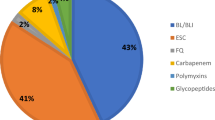

In this study, consumption of antibiotics throughout the years was first assessed. Figure 1 and Table 1 show the DDDs/1000 patient-days and annual usage trends of antibiotics. During the entire study period, the six top-ranked consumed classes of antimicrobial agents were cephalosporins [except for cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor (C/BLI) combinations], β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor (BL/BLI) combinations, quinolones, macrolides, penicillins [except for penicillin/β-Lactamase inhibitor (P/BLI) combinations] and carbapenems. The carbapenem class of antibiotics contained three members in this hospital, including meropenem, imipenem, and biapenem, all of which showed an increasing trend. Among all antibiotics, the most frequently used was piperacillin-tazobactam, followed by cefuroxime and levofloxacin. The annual consumption of several antibiotics significantly decreased during this period, including amphenicols, cephalosporins (except for C/BLI combinations), and lincosamides (P < 0.05). Additionally, there was an increasing trend in the annual consumption of tetracyclines, BL/BLI combinations, and carbapenems (P < 0.05). No statistically significant variation was observed in the consumption of macrolides, aminoglycosides, and quinolones (P > 0.05).

Inpatient antibiotic use for the entire study period. BL/BLI: β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor; C/BLI: cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor; P/BLI: penicillin/β-Lactamase inhibitor. Annual consumption of antibiotics was expressed in defined daily doses (DDDs)/1000 patient-days for various antibiotic classes

Bacterial resistance

Next, bacterial isolates showing carbapenem resistance were assessed.

Bacterial isolates

Consecutive, non-duplicate bacterial isolates were collected from patients treated at the hospital. Altogether 11,813 E. coli isolates, 7412 K. pneumonia isolates, 7583 P. aeruginosa isolates, 4936 A. baumannii isolates, 2007 E. cloacae isolates, and 738 B. cepacia isolates detected between 2012 and 2019 were included in the analysis. Figure 2a shows the trend of the isolation rate of these species. Isolation rates for K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa, and A. baumannii showed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05), while E. coli, E. cloacae, and B. cepacia showed a downward trend over recent years (P < 0.05).

Carbapenem resistance

Figure 2b shows carbapenem resistance trends in Gram-negative bacteria. Carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii significantly increased (P < 0.05) from 18% in 2012 to 60% in 2019. In contrast, a significant decrease in carbapenem resistance of E. cloacae was observed (P < 0.01). However, the remaining four Gram-negative isolates had no significant differences in carbapenem resistance (P > 0.05).

Correlation between antibacterial consumption and carbapenem resistance

In correlation analysis, Figs. 3 and 4 show associations of resistance to carbapenem with antibacterial usage for different classes from 2012 to 2019. Significant positive associations were found of consumption of tetracyclines (P < 0.05), BL/BLI combinations (P < 0.05), C/BLI combinations (only including cefoperazone-sulbactam) (P < 0.01), meropenem (P < 0.05), imipenem (P < 0.01) and carbapenems (P < 0.05) with the rate of CRAB. Conversely, there were significant negative associations of consumption of penicillins (except for P/BLI combinations) (P < 0.01), amphenicols (P < 0.01), first-generation cephalosporins (P < 0.01) and lincosamides (P < 0.01) with the rate of CRAB. Moreover, usage of meropenem (P < 0.05) and carbapenems (P < 0.05) were positively correlated with the rate of CREC. Carbapenem-resistant E. cloacae showed significant negative correlations with usage of P/BLI combinations (P < 0.01), BL/BLI combinations (P < 0.01), meropenem (P < 0.01) and carbapenems (P < 0.01), but a significant positive correlation with total cephalosporins (except for C/BLI combinations) use (P < 0.05). Moreover, carbapenems resistance in B. cepacia was positively correlated with quinolones use (P < 0.05). Unexpectedly, there was no significant correlation between antibacterial consumption and carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa and K. pneumonia (P > 0.05). Moreover, we found that the rise of carbapenems usage was consistent with an increase in the number of Gram-negative isolates resistant to carbapenems (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Associations of resistance to carbapenems with antibacterial usage for the entire study period. BL/BLI: β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor; C/BLI: cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor; P/BLI: penicillin/β-Lactamase inhibitor. Consumption of antibiotic was expressed in defined daily doses (DDDs)/1000 patient-days

Associations of antibiotic usage and carbapenem resistance rates in E. coli, A. baumannii, E. cloacae, and B. cepacia in the entire study period. a Correlation between usage of carbapenems and carbapenem resistance in E. coli. b Associations of usage of tetracyclines, carbapenems, and C/BLI combinations with carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii. c Associations of usage of carbapenems and P/BLI combinations with carbapenem resistance in E. cloacae. d Correlation between consumption of quinolones and carbapenem resistance in B. cepacia. C/BLI: cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor; P/BLI: penicillin/β-Lactamase inhibitor. Consumption of antibiotic was expressed in defined daily doses (DDDs)/1000 patient-days

Discussion

The present study revealed significant associations of consumption of antibiotics with the rates of carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative bacteria.

As shown above, cephalosporins (except for C/BLI combinations) had the largest consumption variety, despite showing a downward trend. In addition, consumption of BL/BLI combinations showed an increasing trend, and piperacillin-tazobactam was the most frequently used antibiotic combination, corroborating previous findings [14]. It is known that a history of using 3rd generation cephalosporins independently predicts extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing K. pneumoniae or E. coli bacteremia [15]. The replacement of 3rd generation cephalosporins by BL/BLI combinations is suitable for reducing the incidence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae [16,17,18]. Additionally, our results revealed significantly increased consumption of carbapenems, corroborating global trends [19, 20]. Furthermore, the present findings confirmed that elevated carbapenem usage was associated with increased number of infections resistant to carbapenems. Yet, it is undeniable that overuse of carbapenems presents an important problem, and carbapenems should be used more rationally.

In this study, the isolation rates of E. coli, E. cloacae, and B. cepacia showed a downward trend. As expected, E. coli was the most common isolate in 2012–2019, but still highly sensitive to carbapenems. Carbapenem resistance rates in K. pneumoniae were significantly lower than the national levels and relatively stable, ranging from 2% in 2012 to 3% in 2019. Previous studies in China revealed CRKP incidence increased from 8.9% in 2005 to 26.3% in 2018 [21, 22]. Surprisingly, the detection rate of CRKP declined for the first time in 2019 [21].

CRAB had the highest rate among all assessed species, rapidly rising between 2012 and 2019, as reported for the whole country [21,22,23]. Since A. baumannii has a resistance rate above 50% to most antibacterial drugs, susceptibility testing should always be performed before its application [24]. Our results showed significant positive associations of resistance to carbapenems in A. baumannii and E. coli with carbapenem consumption, corroborating a large multicenter study in China [25]. Previous studies have indicated that CRAB rate increase is related to carbapenem exposure [26, 27].

Different from findings by Tan et al [28], which showed no significant association between usage of BL/BLI combinations and CRAB prevalence, A. baumannii resistance to carbapenems was positively correlated with cefoperazone-sulbactam usage in the present study. We also observed a positive correlation between tetracycline consumption and A. baumannii resistance to carbapenems. The cefoperazone/sulbactam-based combination regimen, which is usually combined with tigecycline, minocycline, carbapenems or aminoglycosides, is the commonest treatment option for carbapenem-resistant and extensively drug-resistant A. baumannii infections [29]. Therefore, it is understandable that increased consumption of cefoperazone-sulbactam and tetracyclines is associated with carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii.

Unexpectedly, increasing use of carbapenems and P/BLI combinations was significantly correlated with reduced resistance of E. cloacae to carbapenems. Nevertheless E. cloacae has genomic heterogeneity, and consumption of carbapenems is an independent risk factor for infection of imipenem-heteroresistant E. cloacae [30], which may be selected for highly resistant and pathogenic strains. Accordingly, this finding did not provide a strong basis for the selection of antimicrobials to E. cloacae infections. Given the lack of related research on the correlation between antibacterial consumption and carbapenem resistance in E. cloacae, further research is needed to verify this association. It is difficult to treat infections caused by B. cepacia, because of the high level of intrinsic and acquired resistance to many antimicrobial agents. Carbapenems are one of the most reliable antibacterial drugs [31]. Yet, we found that use of quinolones was positively correlated with B. cepacia resistance to carbapenems, which prompts more attention to be paid to the use of quinolones to slow down carbapenem resistance in B. cepacia.

Because of the urgent need to improve the rational use of antibiotics, a multidisciplinary antibiotic team, comprising infectious disease specialists, microbiologists, clinical pharmacists, and clinicians, was established in 2017 in our hospital. This team ensures appropriate administration of antibiotic therapy for inpatients, pointing out medication errors and offering corrective suggestions. Coincidentally, carbapenem resistance rates in K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, E. cloacae, and B. cepacia showed a downward trend from 2017 to 2019. Consequently, reducing the unreasonable use of antibacterial drugs may be an effective measure for reducing the spread of CRGN; however, further studies are needed to confirm these observations.

There were some limitations in this study. Firstly, it was conducted only at one tertiary hospital, while carbapenem resistance rates and antibacterial consumption may vary widely across hospitals; therefore, a multicenter study with more relevant data is needed to explore the correlation between antibacterial consumption and CRGN. In addition, due to the retrospective nature of this study, safety could not be examined, and appropriate and inappropriate uses of antibiotics could not be clearly distinguished. Furthermore, the development of carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative infection is associated with various factors, and the selective pressure of antibacterial drugs is only one of them. Multi-factor analysis needs to be further studied.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated significant correlations between consumption of antibiotics and the rates of CRGN. Implementing proper management strategies and reducing the unreasonable use of antibacterial drugs may be an effective measure for reducing the spread of CRGN, which needs to be further verified in future studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A. baumannii :

-

Acinetobacter baumannii

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- B. cepacia :

-

Burkholderia cepacia

- E. cloacae :

-

Enterobacter cloacae

- P. aeruginosa :

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- K. pneumonia :

-

Klebsiella pneumonia

- CRGN:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria

- CRE:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

- CRAB:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

- CRPA:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- CRKP:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia

- CREC:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli

- ESBL:

-

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase

- BL/BLI:

-

β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor

- C/BLI:

-

Cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor

- P/BLI:

-

Penicillin/β-Lactamase inhibitor

- DDDs:

-

Defined daily doses

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Tacconelli E, Sifakis F, Harbarth S, Schrijver R, van Mourik M, Voss A, et al. Surveillance for control of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):e99–e106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30485-1.

WHO. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. Australas Med J. 2014;7:237.

Friedman ND, Temkin E, Carmeli Y. The negative impact of antibiotic resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(5):416–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.002.

Doi Y. Treatment options for Carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(Supplement_7):S565–s75. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz830.

Potter RF, D'Souza AW, Dantas G. The rapid spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Drug Resist Updat. 2016;29:30–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2016.09.002.

Tomczyk S, Zanichelli V, Grayson ML, Twyman A, Abbas M, Pires D, et al. Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in healthcare facilities: a systematic review and reanalysis of quasi-experimental studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(5):873–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy752.

Cassini A, Högberg LD, Plachouras D, Quattrocchi A, Hoxha A, Simonsen GS, et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European economic area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30605-4.

Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):318–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3.

Qu J, Huang Y, Lv X. Crisis of antimicrobial resistance in China: now and the future. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2240. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02240.

Zou YM, Ma Y, Liu JH, Shi J, Fan T, Shan YY, et al. Trends and correlation of antibacterial usage and bacterial resistance: time series analysis for antibacterial stewardship in a Chinese teaching hospital (2009-2013). Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(4):795–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-014-2293-6.

Aiken AM, Allegranzi B, Scott JA, Mehtar S, Pittet D, Grundmann H. Antibiotic resistance needs global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(7):550–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70709-1.

Wushouer H, Zhang ZX, Wang JH, Ji P, Zhu QF, Aishan R, et al. Trends and relationship between antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic use in Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region, China: based on a 3 year surveillance data, 2014-2016. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(3):339–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2017.09.021.

Guidelines for atc classification and ddd assignment 23rd edition (2020). 2020. Https://www.Whocc.No/atc_ddd_index/.

Zhang D, Hu S, Sun J, Zhang L, Dong H, Feng W, et al. Antibiotic consumption versus the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria at a tertiary hospital in China from 2011 to 2017. J Infect Public Health. 2019;12(2):195–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2018.10.003.

Du B, Long Y, Liu H, Chen D, Liu D, Xu Y, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection: risk factors and clinical outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1718–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-002-1521-1.

Livermore DM, Hope R, Reynolds R, Blackburn R, Johnson AP, Woodford N. Declining cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone non-susceptibility among bloodstream Enterobacteriaceae from the UK: links to prescribing change? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(11):2667–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkt212.

Mascarello M, Simonetti O, Knezevich A, Carniel LI, Monticelli J, Busetti M, et al. Correlation between antibiotic consumption and resistance of bloodstream bacteria in a University Hospital in North Eastern Italy, 2008-2014. Infection. 2017;45(4):459–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-017-0998-z.

Zhou H, Li GH, Chen BY, Zhuo C, Cao B, Yang Y, et al. Chinese expert consensus on response strategies for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing enterobacteriaceae. Natl Med J China. 2014;94:1847–56.

Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, Caudron Q, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, et al. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):742–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70780-7.

Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, Pant S, Gandra S, Levin SA, et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(15):E3463–e70. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1717295115.

Hu F, Zhu D, Wang F, Wang M. Current status and trends of antibacterial resistance in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(suppl_2):S128–s34. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy657.

Hu F, Guo Y, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Wu S, Jiang X, et al. Resistance reported from China antimicrobial surveillance network (CHINET) in 2018. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(12):2275–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-019-03673-1.

Resistance in tertiary hospitals reported from china antimicrobial surveillance network (chinet) in 2019. China antimicrobial surveillance network (chinet) 2020. Http://www.Chinets.Com/document.

Chen BY, He LX, Hu BJ. Consensus of the Chinese specialists for diagnosis, treatment & control of Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012;92(2):76–85.

Yang P, Chen Y, Jiang S, Shen P, Lu X, Xiao Y. Association between antibiotic consumption and the rate of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria from China based on 153 tertiary hospitals data in 2014. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1):137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-018-0430-1.

Kim YA, Park YS, Youk T, Lee H, Lee K. Abrupt increase in rate of Imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii Complex strains isolated from general hospitals in Korea and correlation with Carbapenem administration during 2002-2013. Ann Lab Med. 2018;38(2):179–81. https://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2018.38.2.179.

Zeng S, Xu Z, Wang X, Liu W, Qian L, Chen X, et al. Time series analysis of antibacterial usage and bacterial resistance in China: observations from a tertiary hospital from 2014 to 2018. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:2683–91. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S220183.

Tan CK, Tang HJ, Lai CC, Chen YY, Chang PC, Liu WL. Correlation between antibiotic consumption and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii causing health care-associated infections at a hospital from 2005 to 2010. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2015;48(5):540–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2014.02.004.

Guan X, He L, Hu B, Hu J, Huang X, Lai G, et al. Laboratory diagnosis, clinical management and infection control of the infections caused by extensively drug-resistant gram-negative bacilli: a Chinese consensus statement. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(Suppl 1):S15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.11.004.

Zhou Y, Jia X, Jianchun HE, Y X. Study on clinical characteristics and risk factors for infection of imipenem-heteroresistant Enterobacter cloacae. China Medical Herald. 2019.

Sfeir MM. Burkholderia cepacia complex infections: more complex than the bacterium name suggest. J Inf Secur. 2018;77:166–70.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Danping Qiu for help with the analysis of bacterial isolates and susceptibility testing.

Funding

This study was funded by the Programs for Science and Technology Development of Yulin, China (Grant No. 20202007). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CL and XZ carried out the studies, participated in data collection, and drafted the manuscript. CL, PP and XZ performed statistical analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. LZ1, GM, and LZ2 participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Department of Pharmacy, Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Yulin, Guangxi, 537000, China.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Approval No. 2019052). No consent to participate is required in this study since data from patients have been presented only in a general manner, and no patient can be identified by third parties.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, C., Zhang, X., Zhou, L. et al. Trends and correlation between antibacterial consumption and carbapenem resistance in gram-negative bacteria in a tertiary hospital in China from 2012 to 2019. BMC Infect Dis 21, 444 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06140-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06140-5