Abstract

Background

Schistosomiasis is very common in the southern part of the Yangtze River Basin in China. It is mainly manifested as appendicitis, ulcers, hematomas, and thickening of the intestinal tract. Schistosomiasis of the appendix is rare, mainly manifested as appendicitis, which is easy to be misdiagnosed.

Case presentation

Here we report a rare case of a Chinese female whose intestinal mass manifested as intestinal polyps and was eventually diagnosed pathologically as schistosomiasis infection (appendix schistosomiasis). So far, there are rare relevant cases reported.

Conclusions

Intestinal schistosomiasis is easily misdiagnosed, and appendix schistosomiasis is rare. The final diagnosis requires pathology, especially surgical pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease caused by the trematode of the genus Schistosoma. In the public health sense, it is second only to malaria, infecting more than 200 million people worldwide, causing severe consequences of 20 million people and 100,000 deaths each year [1, 2]. The disease is mainly manifested in the liver, intestine, urogenital tract, and blood system. It mainly manifests as liver fibrosis in China. Schistosomiasis is very common in the southern Yangtze River basin of China, and such patients are under a history of living at the source of the schistosomiasis epidemic. Intestinal schistosomiasis mainly manifests as appendicitis, ulcers, hematomas, and thickening of the intestine [3]. Among them, schistosomiasis infection of the appendix is prone to gangrene and perforation, but a mass in the appendix is rare. The following case describes a female whose intestinal mass appeared as intestinal polyps and was eventually diagnosed with a schistosomiasis infection of the intestine and appendix by pathology. To the best of our knowledge, there are rare relevant cases reported in the Chinese and English literature.

Case presentation

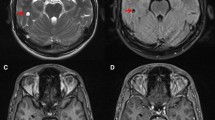

A 65-year-old female from Chaohu, Anhui, China attended our hospital, complaining of slimy stool with mucus for more than 10 years. She had no history of schistosomiasis epidemiology and exposure. She had no family history of colon cancer. The patient did not have any organomegaly on examination. Her blood tests (blood routine, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, tumor marker CA199, CEA, CA125, AFP) and stool tests were normal. Colonoscopy revealed a polypoid-like hump of approximately 2.5 cm × 3.0 cm behind the ileocecal valve, with a thickened superficial duct opening, congestion, and exudation of purulent discharge. The surrounding mucosa was hyperemic, and the appendix was not visible (Fig. 1), the remaining colonic mucosa had no lesions or inflammation. The histopathology of the ileocecal area showed severe chronic inflammation and lymphoid follicular hyperplasia. The entire abdominal CT scan before the colonoscopy showed a soft tissue approximately 2.3 cm × 1.8 cm in the ileocecal area with irregular borders, and moderately continuous enhancement after enhancement (Fig. 2).

We initially diagnosed the bulge of the ileocecal as intestinal polyps and prepared to undergo endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) surgical resection, however, during the operation we found that the lesions may not be completely cleared, the patient finally decided to undergo surgery. In this colonoscopy, we performed the pathological examination of the same part, and the results were similar to the previous results. Laparoscopy showed no ascites in the abdominal cavity, rich omentum tissue, no metastasis in the liver and peritoneum, and the ileocecum and ascending colon omentum were wrapped inside the abdominal wall. The tumor was located at the opening of the appendix in the ileocecal region, which was also the root of the appendix, without invading the serosa.

The tumor markers of the patient were normal, but the malignant tumor could not be ruled out. The surgeon and his family decided to completely remove the right half colon after consultation. Histopathology clearly showed that there were a large number of schistosome eggs deposited in the ileocecal region and the appendix, with a lot of lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils infiltrated, lymphoid tissue proliferation, and lymphoid follicle formation (Fig. 3). We carried out a total of three pathological tests and finally diagnosed with intestinal schistosomiasis (ileucopia, appendix).

Discussion and conclusions

Schistosomiasis is still prevalent in China. An epidemiological survey in the Chaohu area of Anhui Province shows that schistosomiasis is still prevalent there [4,5,6]. Oncomelania hupensis is the intermediate host of schistosomiasis. Research data showed that (1) a total of 314 residents were detected by indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA), but there were no positives; (2) a total of 302 mobile population were detected by IHA, and the positive rate of antibody was 1.32%; (3) 30 individuals were examined by stool tests, and the positive rate was 20% [6]. The patient is from Chaohu, Anhui Province, but she has no relevant epidemiological history, we can’t rule out the possibility of unknown potential infection.

The diagnosis of intestinal schistosomiasis is very difficult, and it is almost impossible to confirm the diagnosis before surgery. It may help to diagnose by asking for the previous history. The gold standard for the diagnosis of an ongoing schistosome infection has for decades been the detection of eggs in a fecal smear. However, the positive rate of fecal worm eggs is very low, histopathology and serology can also help diagnosis [7]. The low positive rate of fecal eggs may be related to fecal sampling, specimen preservation and time, etc. The final diagnosis of our patient was the discovery of schistosome eggs in surgical specimens.

Schistosome eggs can invade many parts of the gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, etc., but mainly cause lesions in the liver, spleen, and colon, causing tissue fibrosis or bleeding [8]. Intestinal schistosomiasis is classified into three types of enteritis acute, chronic, and mixed type, the latter was an important and independent type. The main mechanism of schistosomiasis is that cercariae invade the human body and invade the portal vein system through blood circulation. Eggs fall off with necrotic tissue, enter the intestinal cavity, and deposit in the appendix cavity. Mature worm eggs containing hairy maggots release soluble antigens through the pores of the eggshell and activate the host’s immune system and cause a local immune response.

Acute patients present with immune complex disease, while chronic patients present with T lymphocyte-mediated delayed allergies, which may be accompanied by the deposition of antigen-antibody complexes to form eosinophilic granuloma. With the degeneration, necrosis, and calcification of worm eggs, infiltrating cells were replaced by monocytes and fibroblasts to form chronic granulomas [9].

The disease was easily misdiagnosed as colon cancer, ulcerative colitis, and intestinal tuberculosis. Isolated schistosomiasis infections are rare. Colonoscopy findings and repeated biopsy from the suspected lesions were essential for getting the correct diagnosis, but the positive rate was low, sometimes surgery was needed to confirm the diagnosis. The prevention and control of schistosomiasis are very important, and medical staff needs to strengthen their understanding of schistosomiasis to avoid missing diagnosis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current case reports are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ESD:

-

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

- IHA:

-

Indirect hemagglutination assay

References

Darcy S, Jenkins-Holick, Kaul TL. Schistosomiasis. Urol Nurs. 2013;33(4):163–70.

Colley DG, Addiss D, Chitsulo L. Schistosomiasis. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(Suppl 2):150–1.

Jones HJ, Ibrahim AE, Deroda JK. Schistosomiasis of the appendix inthe UK. Sr Med Assoc J. 2005;7(8):533–4.

Liu H, Sha JJ, Huang H, et al. Investigation on schistosomiasis cognitive levels of people from Chaohu area. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2015;27(6):621–4 Chinese. PMID: 27097483.

Cao ZG, Wang TP, Wu WD, et al. Potential impact of water transfer project from Yangtze River to Huaihe River on snail spread and schistosomiasis transmission. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2007;25(5):385–9 Chinese. PMID: 18441990.

Cao ZG, Gao P, Wang TP, et al. Evaluation on transmission risk of schistosomiasis japonica in the Chaohu Lake area. J Trop Dis Parasitol. 2013;11(4):211–3 222.Chinese.

Wilson AR. The Problem with Diagnosis of Intestinal Schistosomiasis. Ebiomedicine. 2017;25:16–7 S2352396417303961.

Botes SN, Ibirogba SB, McCallum AD, Kahn D. Schistosoma prevalence in appendicitis. World J Surg. 2015;39(5):1080–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-2954-3.

Mosli MH. Schistosomiasis presenting as a case of acute appendicitis with chronic mesenteric thrombosis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2016;2016(1):5863219.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the patient in the case and her family, who helped us in preparing the data.

Funding

There was no funding for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZXL, SJZ, HLQ, YWY, and ZML cared for and managed the patient and did a literature search. ZXL was responsible for writing the manuscript. ZXL and SJZ contributed equally on the article. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

All of the authors currently work in the Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, 230001, P.R. China.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. Patient gave written consent for personal or clinical details along with any identifying images to be published in this study. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

XiuLi Zhu and JiZhong Song are co-first authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, X.L., Song, J.Z., Yu, W.Y. et al. Intestinal schistosomiasis masquerading as intestinal polyps. BMC Infect Dis 21, 434 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06125-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06125-4