Abstract

Background

Globally, tuberculosis (TB) remains the leading cause of death from a single infectious disease. TB treatment outcome is an important indicator for the effectiveness of a national TB control program. This study aimed to assess treatment outcomes of TB patients and its determinants in Batkhela, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was designed using all TB patients who were enrolled at District Head Quarter (DHQ) Hospital Batkhela, Pakistan, from January 2011 to December 2014. A binary logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with successful TB treatment outcomes defined as the sum of cure and completed treatment.

Results

A total of 515 TB patients were registered, of which 237 (46%) were males and 278 (53.98%) females. Of all patients, 234 (45.44%) were cured and 210 (40.77%) completed treatment. The overall treatment success rate was 444 (86.21%). Age 0–20 years (adjusted odds ratio, AOR = 3.47; 95% confidence interval, CI) = 1.54–7.81; P = 0.003), smear-positive pulmonary TB (AOR) = 3.58; 95% CI = 1.89–6.78; P = < 0.001), treatment category (AOR = 4.71; 95% CI = 1.17–18.97; P = 0.029), and year of enrollment 2012 (AOR = 6.26; 95% CI = 2.52–15.59; P = < 0.001) were significantly associated with successful treatment outcome.

Conclusions

The overall treatment success rate is satisfactory but still need to be improved to achieve the international targeted treatment outcome. Type of TB, age, treatment category, and year of enrollment were significantly associated with successful treatment outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, tuberculosis (TB) remains the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), ranking above human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [1, 2]. In 2018, an estimated 10 million incident TB cases and 1.6 million deaths due to TB were reported globally [1]. The magnitude of the disease varies from country to country with more prevalent in low-income countries [1, 2].

Increasing the rate of successful treatment outcome is one of the strategies for effective control of TB in the community. The End TB Strategy defines targets for 2030; to decrease the incidence rate by 80% (new cases per 100,000 population per year) and 90% reduction in the number of TB deaths compared with levels in 2015 [3]. However, successful treatment outcome has increased in several countries following the implementation of Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course (DOTS) program [4]. TB is still a major health problem in Pakistan, with an estimated 510,000 new TB cases and approximately 15,000 drug resistant TB cases reported every year [5]. Recently, a standardized TB prevention and control program that regularly monitors the incidence of TB and as well as drug susceptibility testing in the population has been launched at Hayatabad Medical Complex Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province [6]. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan several studies have been conducted on the prevalence of TB [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Monitoring treatment outcomes among war affected countries such as Pakistan provides evidence to assess the effectiveness of TB control programs. There are few epidemiological studies conducted in Pakistan on TB treatment outcomes [13,14,15,16,17]. However, data are limited between 2011 and 2014 in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa for the analysis of trends. Moreover, identifying factors associated with poor treatment outcomes of patients with TB in war affected region provides additional information for national and global TB programs to implement targeted interventions aimed at prevention and management. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the TB treatment outcomes and its determinants in Batkhela, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, between 2011 and 2014.

Methods

Study design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted among TB patients who enrolled at District Head Quarter (DHQ) Hospital Batkhela, Pakistan, from January 2011 to December 2014.

Setting

Batkhela is the capital city of Malakand district and it is one of the popular business city in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Malakand district is situated in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. The total population of the district is 720,295 (2017 census) [18]. The DHQ Hospital Batkhela, providing health care facilities to the local residence of Batkhela and district Malakand. The area has been providing humanitarian protection and shelter for a large number of refugees from different districts of Malakand division during flood and war. At the hospital, TB treatment is prescribed based on the recommendations of the national TB guidelines, which is based on recommendations from WHO guidelines. All newly diagnosed TB patients receive a standardized regimen of first-line TB drugs that consists of an 2-month intensive phase with a combination of pyrazinamide (Z), isoniazid (INH), ethambutol (E), and rifampicin (R) a 2-month continuation phase with a combination of rifampicin (R) and ethambutol (E). However, certain groups of TB patients (such as MDR-TB patients) cannot receive the first-line regimen, requiring second-line regimens [19, 20].

Participants

All TB patients who were enrolled at DHQ Hospital between 1st January 2011 and 31st December 2014 were included.

Data sources

Data were extracted from patients’ TB registration books and medical records by trained data collectors. The registration books contained basic information such as socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

Variables

Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers.

Laboratory procedure

According to the standard protocol the sputum was collected from the suspected patients having symptom of TB in 5 ml sterile bottle, after collection of sputum the bottle were kept in 15 ml sterile bottle to avoid the leakage of the infectious samples. The samples were labeled and further process by the laboratory technician of the hospitals. Smear microscopy with Ziehl-Neelsen staining and fluorescence microscopy are used in the Hospital for both the diagnosis and monitoring of TB [21].

Standard definition

TB treatment outcomes and clinical cases were defined according to the standard World Health Organization (WHO) definitions (Table 1). In this study, treatment success was defined as a sum of cured and treatment completed; and poor treatment was defined as the sum of treatment failure, death or lost to follow up.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were checked for completeness by principal investor. Data were entered, cleared and descriptive analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Binary logistic regression model was used to analyze the association between treatment outcome and potential determinate variables at 95% confidence interval. P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the patients

A total of 515 TB patients, registered and treated for TB at DHQ Hospital between January 2011 to December 2014, were included in this study. Of these, 278 (53.98%) were female and 185 (35.92%) were age less than 20 years (Table 2).

Clinical characteristics of the patients

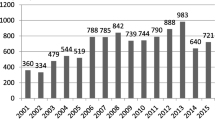

Of the total patients, 252 (48.93%) were smear positive PTB, 82 (15.92%) were smear negative PTB and 181 (35.15%) were EPTB as shown in Table 2. Majority of the patients 493 (95.72%) were new TB cases, and 503 (97.7%) were treatment category I (CAT-I). The number of cases diagnosed with TB in the hospital was increased from 116 (22.52%) in 2011 to 161 (31.26%) in 2014.

Treatment outcomes

The overall TB treatment success rate (i.e. cured and treatment completed) in Batkhela was 444/515 (86.21%). Of all patients, 234 (45.44%) were cured, 210 (40.77%) completed treatment, 14 (2.72%) died, 20 (3.88%) lost to follow-up, and 3 (0.58%) were transferred out (Table 3). The treatment success rate was higher among female 243/278 (87.41%) than male 201/237 (84.81%) and increased over time.

Factors associated with treatment success

Table 4 shows factors associated with successful TB treatment outcomes. Type of TB, age, and year of treatment commencement were significantly associated with successful treatment outcomes. The odds of successful treatment outcomes was higher among patients with age group 0–20 years (AOR = 3.47; 95% CI: 1.54–4.7.81), 21–40 years (AOR = 2.76; 95%CI: 1.26–6.03), and 41–60 years (AOR = 2.82; 95%CI: 1.08–7.35) compared to patients with age group > = 61 years. The study also found that the odds of successful treatment outcomes was three times higher among smear positive pulmonary TB patients than extra pulmonary TB patients (AOR = 3.58; 95% CI: 1.89–6.78). The odds of successful treatment outcomes were higher among patients with treatment CAT-I than patients with treatment category II (CAT-II) (AOR = 4.71, 95%CI: 1.17–18.97).

Discussion

This study was designed to assess treatment outcomes and determine predictors of poor treatment outcomes among patients with TB in war affected region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. We found that the overall TB treatment success (i.e. having an outcome of cured or treatment completed) at the end of the treatment was 86.2%, which is similar to other resource-constrained countries such as India (81–83%) [23,24,25], Ethiopia (85.6%) [26], Nigeria (83.1%) [27], Uzbekistan (83%) [28], Thailand (78.5–87.5%) [29], and higher than war affected countries such as Somalia (81.8%) [30], Iran (83.1%) [31] and Afghanistan (77.7%) [32]. However, the treatment success rate in our study was lower than the treatment success rate reported in the previous studies in Pakistan [13, 33]. It is also lower than the global End TB Strategy targets. Demographic and clinical factors such as type of TB, year of treatment commencement, and age, were significantly associated with treatment outcomes of patients with TB.

Our study showed that patients with age less than 60 years were nearly three times more likely to get successful treatment outcome as compared to patients with age greater than 61 years. These results are consistent with previous studies conducted in Ethiopia [34]. This may be due to the fact that older age patients are at a higher risk of death due to ageing. Another reason for low treatment outcome in older age patients could be because older age patients might be at higher risk of having chronic comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, hypertensions, and cancers. Low socio-economic status, poor adherence to treatment, and difficulty of traveling and arriving early at health facilities for DOTS could be also other reasons for low treatment outcomes in older age patients. These findings highlight the importance of providing close follow up for older age patients to increase their successful treatment outcome.

The other important finding is that smear positive pulmonary TB patients were more likely to have a successful treatment outcome than other types of TB patients. This result is consistent with previous studies conducted in Ethiopia [34]. This could be explained by the fact that smear positive pulmonary TB patients might be diagnosed easily and started the treatment promptly and may have close follow by health professionals. All TB diagnosed patients were treated at DOTS clinics using regimens recommended by WHO. Two types of treatment category were set CAT-I and CAT-II. Results of the current study show that patients with treatment CAT-I was more likely to have successful treatment outcomes than patients with treatment CAT-II.

Our study also showed that patients who started treatment before 2014 were more likely to have successful treatment outcomes than patients who started treatment in 2014. The finding indicated that successful treatment outcomes were decreased overtime from (87.0%) in 2011 and (94.9%) in 2012 to (73.9%) in 2014. This may be related to the desaturation of health care systems and TB treatment services of country because of the war. It could be also due to increased number of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) which is defined as TB that is resistant to the two most powerful first-line TB drugs (i.e. isoniazid and rifampicin). We also found that the overall prevalence of smear positive PTB was high among reported cases, which concurs with previous studies showing that majority of patients taking TB treatment were smear positive PTB [33]. The smear positive PTB patients are dangerous and can easily spread the infection in the community. Early diagnosis and treatment of such cases are very important and necessary to reduce the progression of TB. The overall case fatality rate was (2.72%) which is high from previous published studies [35]. The high rate of mortality among TB patients could be attributed to less access to hospitals, at door step availability of least health diagnostic facilities, no early diagnosis and treatment of the disease, poverty, and poor nutritional status in our society.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, since the study was based on secondary data, some important clinical variables such as HIV, diabetes mellitus, and other co-morbidities as well as behavioral factors such as alcohol drinking and smoking were not available in the registers and therefore were not included in our study. Secondly, in this study those patients who had documented evidence of completion were counted as having a successful treatment outcome, whereas they may have undetected failure of therapy. This may lead to overestimation of the treatment outcome rate in our study. Third, as the study used data reported between 2011 and 2014, we have not assessed recent treatment outcomes, and a longer follow-up period will be required to assess longer-term trends in treatment outcomes, which is out of the scope of the current study.

Conclusion

The overall treatment success rate is satisfactory but still need to be improved to achieve the international targeted End TB Strategy milestones. Type of TB, age, treatment category, and year of enrollment were significantly associated with successful treatment outcomes. Successful treatment outcomes were decreased over time which is an alarming signal for MDR-TB.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used, generated and/or analyzed in this study are available free of cost from the principal author/corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- DHQ:

-

District Head Quarter

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- DOTS:

-

Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- AFB:

-

Acid Fast Bacilli

- PTB:

-

Pulmonary Tuberculosis

- EPTB:

-

Extra-pulmonary Tuberculosis

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- CAT-I:

-

Category-I

- CAT- II:

-

Category-II

- COR:

-

Crude Odds Ratio

- MDR-TB:

-

Multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis

References

Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

MacNeil A, Glaziou P, Sismanidis C, Maloney S, Floyd K. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis and progress toward achieving global targets-2017. Morb Mortal Wly Rep. 2019;68(11):263–6. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6811a3.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. IGO.

Otu AA. Is the directly observed therapy short course (DOTS) an effective strategy for tuberculosis control in a developing country? Asian Pacific J Trop Dis. 2013;3(3):227–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2222-1808(13)60045-6.

WHO EMRO. Tuberculosis: Pakistan. [Retrieved on 22-11-2019]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/pak/programmes/stop-tuberculosis.html.

Khan MT, Malik SI, Ali S, Masood N, Nadeem T, Khan AS, et al. Pyrazinamide resistance and mutations in pncA among isolates of mycobacterium tuberculosis from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3764-2.

Ayaz S, Tahira N, Khan S, Khan SN, Rubab L, Akhtar M. Pulmonary tuberculosis: still prevalent in human in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Pakistan J Life and Soc Sci. 2012;10(1):39–41.

Ahmad TA. Epidemiology of tuberculosis: current status in district Dir (lower) Pakistan. Int J Sci Eng Res. 2013;4(11):755–63.

Ahmad T, Ahmad K, Rehman MM, Khan A, Jadoon MA, Rehman MN, et al. Tuberculosis is still a prevalent disease in population of district Dir (lower) Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. Glob Vet. 2014;12(1):125–8. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.gv.2014.12.01.82277.

Ahmad T, Zohaib DM, Zaman Q, Saifullah JMA, Ismail M, Tariq M, et al. Prevalence of tuberculosis infection in general population of district Dir (lower) Pakistan. Middle-East J Sci Res. 2015;23(1):14–7. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2015.23.01.91145.

Ahmad T, Jadoon MA, Khattak MN. Prevalence of sputum smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis at Dargai, district Malakand, Pakistan: a four year retrospective study. Egyptian J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2016;65(2):461–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcdt.2015.12.004.

Lalokhil MS, Khan A, Adnan M, Khan MI. Prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis in district Mardan Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Microbiology. 2019;3(1):1–7.

Ahmad T, Haroon KM, Khan MM, Ejeta E, Karami M, Ohia C. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment short course and its determinants in Shangla, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan: a retrospective study. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2017;6:360–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmy.ijmy_69_17.

Atif M, Anwar Z, Fatima RK, Malik I, Asghar S, Scahill S. Analysis of tuberculosis treatment outcomes among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Bahawalpur, Pakistan. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):370. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3473-8.

Akhtar S, Rozi S, White F, Hasan R. Cohort analysis of directly observed treatment outcomes for tuberculosis patients in urban Pakistan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(1):90–6.

Syed MA. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients registered at DOTs Centre in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;21:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2014.03.953.

Abbasi S, Tahir M. Effectiveness of directly observed therapy short course (DOTS) in patients with tuberculosis registered at Federal General Hospital, Islamabad. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;73:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.04.4194.

Block Wise Provisional Summary Results of 6th Population & Housing Census-2017 [Retrieved on 06-02-2019]. Available from: http://www.pbscensus.gov.pk/sites/default/files/bwpsr/kp/malakand%20protected%20area_blockwise.pdf.

World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes, third edition. Revision approved by STAG, June 2004. WHO/CDS/TB/2003.313. [Retrieved on 06-02-2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/tb_2003_313_chap4_rev.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of tuberculosis, American thoracic society, CDC, and infection diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:1–77 [Retrieved on 06-02-2019]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5211a1.htm.

Pai M, Behr MA, Dowdy D, Dheda K, Divangahi M, Boehme CC, et al. Nature reviews disease primers. Tuberculosis. 2016;2:16076. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.76.

WHO. Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis – 2013 revision (updated 2014) Geneva, Switzerland; 2013.

Ramya VH, Gayathri G, Gangadharan V. A study of treatment outcomes of pulmonary tuberculosis and extrapulmonary tuberculosis patients in a tertiary care Centre. Int J Adv Med. 2017;4(4):1133–7. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3933.ijam20173246.

Akarkar NS, Pradhan SS, Ferreira AM. Treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients at an urban health Centre, Goa, India- eight year retrospective record based study. Int J Comm Med Public Health. 2017;4(3):831–4. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20170767.

Ramachandran G, Kupparam HKA, Vedhachalam C, Thiruvengadam K, Rajagandhi V, Dusthackeer A, et al. Factors influencing tuberculosis treatment outcome in adult patients treated with thrice-weekly regimens in India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(5):e02464–16. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02464-16.

Trivedi PR, Khakhkhar TM. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment short-course and factors affecting the outcome in tertiary care hospital. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2019;8(5):981–6. https://doi.org/10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20191588.

Sakajiki MA, Garba B, Ibrahim Y, Mohammed BA, Abdullahi U, Sada KB. IbrahimTM. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis at a specialist hospital in North Western Nigeria - a 30 months retrospective study. Pakistan J Chest Med. 2018;24(1):04–9.

Gadoev J, Asadov D, Tillashaykhov M, Tayler-Smith K, Isaakidis P, Dadu A, et al. Factors associated with unfavorable treatment outcomes in new and previously treated TB patients in Uzbekistan: a five year countrywide study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128907. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128907.

Somsong W, Lawpoolsri S, Kasetjaroen Y, Manosuthi W, Kaewkungwal J. Treatment outcomes for elderly patients in Thailand with pulmonary tuberculosis. Asian Biomed. 2018;12(2):75–82. https://doi.org/10.1515/abm-2019-0004.

Ali MK, Karanja S, Karama M. Factors associated with tuberculosis treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients attending tuberculosis treatment centres in 2016–2017 in Mogadishu, Somalia. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:197. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.28.197.13439.

Khazaei S, Hassanzadeh J, Rezaeian S, Ghaderi E, Khazaei S, Hafshejani AM, et al. Treatment outcome of new smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Hamadan, Iran: a registry-based cross-sectional study. Egyptian J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2016;65:825–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcdt.2016.05.007.

Rahimi BA, Rahimy N, Ahmadi Q, Hayat MS, Wasiq AW. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis treatment regimens in Kandahar, Afghanistan. Indian J Tuberc. 2020;67(1):87In press, corrected proof, available online 7 November 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtb.2018.10.008.

Ahmad T, Jadoon MA. Cross sectional study of pulmonary tuberculosis at civil hospital Thana, district Malakand Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. World J Zool. 2015;10(3):161–7. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wjz.2015.10.3.9578.

Beza MG, Wubie MT, Teferi MD, Getahun YS, Bogale SM, Tefera SB. A five years tuberculosis treatment outcome at Kolla Diba health center, Dembia District, Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective cross-sectional analysis. J Infect Dis Ther. 2013;1(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2332-0877.1000101.

Saleem M, Ahmad W, Jamshed F, Sarwar J, Gul N. Prevalence of tuberculosis in Kotli, Azad Kashmir. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2013;25(1–2):175–8.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Department of Microbiology, Hazara University Mansehra and DHQ Hospital Batkhela during the current study.

Funding

This study was supported by Chinese National Natural Fund (81573258), Jiangsu Provincial Six Talent Peak (WSN-002). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TA: Study design, data collection and extraction, paper writing and analysis; MAJ: Study design and critical review; MK1, H: Help in data collection and paper writing; MMK, AH, THM, MW, HJ: Technical assistance and literature search; EE: Help in statistical analysis. MAJ, MK1, H, MK2, KAA: Critical reviewed and edited the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethical research committee (Advanced Studies and Research Board) of Hazara University Mansehra, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan [No. HU/R&P/ASRB/2015/1995]. The study was conducted in accordance with approval guideline and prior permission was granted by the higher authority of DHQ Hospital Batkhela. To ensure confidentiality of the information collected from TB registration books, name or identification number of TB patient was not included in the data collection sheet.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, T., Jadoon, M.A., Khan, M. et al. Treatment outcomes of patients with tuberculosis in war affected region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis 20, 463 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05184-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05184-3