Abstract

Background

Breakthrough invasive fungal infections (bIFIs) are an area of concern in the scarcity of new antifungals. The mixed form of bIFIs is a rare phenomenon but could be potentially a troublesome challenge when caused by azole-resistant strains or non-Aspergillus fumigatus. To raise awareness and emphasize diagnostic challenges, we present a case of mixed bIFIs in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Case presentation

A newly diagnosed 18-month-old boy with acute lymphoblastic leukemia was complicated with prolonged severe neutropenia after induction chemotherapy. He experienced repeated episodes of fever due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli bloodstream infection and pulmonary invasive fungal infection with Aspergillus fumigatus (early-type bIFIs) while receiving antifungal prophylaxis. Shortly after pulmonary involvement, his condition aggravated by abnormal focal movement, loss of consciousness and seizure. Cerebral aspergillosis with Aspergillus niger diagnosed after brain tissue biopsy. The patient finally died despite 108-day antifungal therapy.

Conclusions

Mixed bIFIs is a rare condition with high morbidity and mortality in the patients receiving immunosuppressants for hematological malignancies. This case highlights the clinical importance of Aspergillus identification at the species level in invasive fungal infections with multiple site involvement in the patients on antifungal prophylaxis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cerebral aspergillosis usually occurs secondary to fungemia after inhaling the fungal spores, proliferating and invading the pulmonary alveolar arteries, after the direct invasion from adjacent structures (sinuses), iatrogenic/penetrating trauma, medical surgery, and contamination of indwelling catheters (ventriculoperitoneal shunts). Multiple brain abscesses could be developed by different mechanisms such as direct angioinvasion, thrombosis, and infarction, mycotic aneurysm, or even intracranial hemorrhage [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The incidence of cerebral aspergillosis is not known and is directly related to the underlying diseases and host factors. Although the overall prevalence is estimated to be less than 7%, in the high-risk population such as cancer patients the reported frequency is as high as 20–40% [6, 7]. In recent years, the reports of such infections have increased due to the rising number of immunocompromised patients (human immunodeficiency virus infections, patients with chemotherapy or transplant recipients), and improved diagnostic modalities (radiological and microbiological) [3, 8,9,10].

Breakthrough invasive fungal infection (bIFI) defined as a new fungal infection in the patients receiving therapeutic or prophylactic antifungal agents. Concomitant fungal pneumonia with central nervous system (CNS) infection is a rare occurrence in patients with hematological malignancies, especially those on anti-fungal (AF) prophylaxis. In this report, a mixed pulmonary and CNS aspergillosis reported in a pediatric patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and we discuss bIFIs during antifungal (AF) prophylaxis.

Case presentation

An 18-month-old boy referred to Amir Medical Oncology Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran, because of scattered bruising patches on his trunk and limbs. He was pale and suffering from mild upper respiratory tract symptoms for several days before admission. In the primary laboratory investigation, severe anemia and thrombocytopenia [Hemoglobin: 4 g/dl (1–6 years: 11.5–13.5 g/dL), platelet count: 10000/mcL (150–400 /microliter) and, white blood cell count (WBC): 106000 cells/mcL (1–6 years: 5000–17,000 cells/microliter)] were detected. B cell ALL diagnosed following bone marrow aspiration/biopsy. Induction chemotherapy started with vincristine, PEG-asparaginase, and daunorubicin. Prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was initiated simultaneously with his chemotherapy. About 9 days later, his absolute neutrophilic count dropped rapidly (total WBC count: 500 cells/mcL) when he was afebrile. Acute phase reactants were within normal limits (C-reactive protein concentration and erythrocyte sedimentation rate levels were negative and 3, respectively). Prophylactic liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome, USA) started, and the galactomannan test (GM, Aspergillus antigen) was requested (twice per week) for early detection of invasive aspergillosis (IA). Fever developed on the12th day post-admission. Complete sepsis workup was done and meropenem was initiated. Plain X-ray revealed no new parenchymal involvement. Peripheral and central catheter blood cultures performed for the patient using an automated blood culture system (BACTEC medium Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA). Both cultures were positive for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli with similar antibiotic susceptibility patterns (sensitive to meropenem, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and amikacin). Lock-therapy for catheter bloodstream infection with ciprofloxacin performed (based on hospital protocol). Control blood cultures became negative after 5 days of targeted antibiotic treatment. The chest X-ray was normal at that time (Fig. 1).

The second episode of fever occurred a few days later despite the complete course of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. All cultures repeated, and diagnostic workup upgraded. The stool examined for Clostridium (C) difficile toxin gene by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) after culture for C. difficile. Quantitative PCR for Cytomegalovirus and Mannan test requested in addition to routine indirect mycological (Real-time PCR for Aspergillus and Candida species) and GM tests. The serum GM test was positive during the second investigation (Fig. 2). Spiral chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed small ground-glass opacities in the right and left hemithorax (Fig. 3).

Intravenous voriconazole started and diagnostic bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) scheduled. The result of BAL culture was positive for A. fumigatus on sabouraud dextrose agar (Merck, Germany) (Fig. 4). The minimum inhibition concentrations (MIC) for amphotericin B, caspofungin, voriconazole, posaconazole, and itraconazole for A. fumigatus were 4 mg/l, 0.032 mg/l, 0.25 mg/l, 0.032 mg/l, and 0.125 mg/l, respectively.

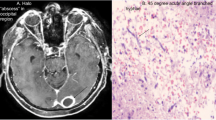

A few days later, the patient’s condition deteriorated suddenly by abnormal focal movement in his right upper limb, loss of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale: 4), and seizure. He transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed total cell count 15 without WBC, protein 164 mg/dl, Lactate dehydrogenase 65 U/L (normal range < 70 U/L), and sugar 48 mg/dl. Brain CT scan showed extensive left hemisphere intracerebral hemorrhage (Fig. 5a). A pediatric neurosurgeon provided external drainage and hemorrhage drained. Fungal PCR and culture from CSF requested, all with negative results. Caspofungin (Cancidas) was added to his antifungal regimen because mucormycosis or fusariosis rarely develop during Ambisome prophylaxis [11]. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed multiple brain abscesses (Fig. 5b).

Brain biopsy performed because of persistent fever despite extensive medical and surgical treatment. KOH revealed septate hyphae (Fig. 4). Tissue biopsy cultured, which was positive for mold infection, the isolated species identified by beta-tubulin gene and sequencing [12]. All other requested diagnostic tests and bacterial culture on brain biopsy were negative. The beta-tubulin gene sequence result was compared with the GenBank database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and revealed that the isolated species is Aspergillus niger. It deposited in the GenBank database with accession number MT561886. The MIC for amphotericin B, caspofungin, voriconazole, posaconazole, and itraconazole in isolated A. niger were 8 mg/l, 0.032 mg/l, 0.5 mg/l, 0.032 mg/l, and 0. 25 mg/l. The patient stayed in the hospital for several weeks without any changes in his clinical status and died due to sudden cardiac arrest associated with severe CNS Aspergillus infection, renal impairment, and septic shock 142 days after admission and 108 days after AF therapy.

Discussion and conclusions

Patients with hematological malignancies are at increased risk of various infections, including IFIs. The risk is higher among those receiving chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, ALL, patients during induction-remission chemotherapy, graft versus host disease, and corticosteroid therapy. AF prophylaxis recommended in high-risk patients in the presence of prolonged severe neutropenia (ANC < 500 cells/μL > 7 days) [13]. Even with the first-line choices, AF prophylaxis may be unsuccessful in about 3–14% of the patients at risk of IFIs [14,15,16]. The occurrence of bIFIs during primary AF prophylaxis at initial remission-induction chemotherapy is considered as “early bIFIs”, while “late bIFIs” usually develops during re-induction for relapsed leukemia, and prolonged corticosteroid treatment [15].

There are some risk factors for developing bIFIs like the occurrence of IFIs due to resistant pathogens, development of resistance in previously susceptible fungi, inadequate absorption (mucositis, enteritis), abnormal metabolism (CYP2C19 heterogenicity), ineffective distribution, drug interactions, and conditions that perpetuate the infection (refractory/relapsed hematological illness). Although Mucormycosis is considered a common cause of bIFIs in those on azole prophylaxis in some reports, other mold infections such as Aspergillus and non-Aspergillus species are also well-known as etiologic agents [14]. The proportion of bIFIs caused by mold varies between 27 and 73% [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The prevalence of bIFIs may also be affected by the AF class. For example, bIFIs in the patients treated with caspofungin usually are caused by Aspergillus spp. [25]. Data regarding post-amphotericin prophylaxis bIFIs are limited, but Aspergillus spp. (A. terreus), Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and even Mucorales have been reported [23].

The emergence of azole-resistant pathogens warrants careful adherence to the stewardship programs in high-risk settings such as hematology/oncology wards [26, 27]. The reported prevalence of azole-resistant strains is more than 50% in the literature [14]. However, the rate is much lower for other AF agents such as amphotericin. In the present case, pulmonary IA developed 24 days after AF prophylaxis, during induction-remission chemotherapy.

Early diagnosis and antifungal therapy are vitally crucial for the best outcome of the patient. The treatment of infections caused by fungi may differ, so it is essential to confirm the genus by culture, PCR, and sequencing. Both microscopic examination and culture are insensitive, and therapy should not withhold in the absence of such confirmation. Non-invasive methods like serum biomarkers (GM and beta-D-glucan assays) are established for the diagnosis of IA [28]. Molecular techniques can also help the clinicians to detect fungal infections in the early stages of IA [29, 30]. The monitoring of both serum GM and blood-PCR is associated with an earlier diagnosis of IA [31]. There are limited reports regarding the diagnosis of CNS infections using the GM assay and PCR. In our case, the GM test was positive in both CSF and blood, while real-time PCR was positive only in the former. Nevertheless, both tests were positive in the third CSF sample, indicating that an accurate diagnosis demands multiple sampling.

In this study, two Aspergillus species isolated from the patient. Diagnosis of A. niger is difficult because Aspergillus section Nigri is a pigmented fungus (also called black Aspergilli) and morphologically is very similar to A. niger. Simões and coworkers by colony morphologic characterizing, microscopic examination, and spectral mass analyses were reported species of Aspergillus section Nigri including Aspergillus aculeatus, Aspergillus brasiliensis, Aspergillus carbonarius, Aspergillus ellipticus, Aspergillus ibericus, Aspergillus japonicas, Aspergillus lacticoffeatus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus phoenicis, Aspergillus sclerotioniger, Aspergillus tubingensis, Aspergillus uvarum, and Aspergillus vadensis [32]. The infections caused by Aspergillus section Nigri are rare and more of these were categorized in A. niger infections. Gautier and coworker reported, from 85 A. niger isolated from respiratory samples, 40 species were diagnosed as A. tubingensis by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, infected patients suffered from different types of chronic respiratory failure [32]. Therefore, Aspergillus niger identified by beta-tubulin gene and sequencing in this case.

In our case, although both isolates showed low MIC to all tested Azoles, high MIC to amphotericin B was found. Amphotericin resistant A. niger documented in the present case report warrants special consideration in high-risk patients receiving amphotericin B for prophylaxis. Thus, given the different AF susceptibility patterns, identification of the Aspergillus at the species level is suggested [13, 33] and should be considered in multiple site involvement.

CNS infections may happen as an occult asymptomatic extra-pulmonary involvement during the diagnostic evaluation of febrile neutropenic patients or symptomatic form, which usually developed after a few weeks (median of 2 weeks) of pulmonary manifestation (range: 5–283 days) [34]. In our case, the patient’s first neurological signs and symptoms were developed as the consequence of extensive CNS hemorrhage concomitantly with pulmonary involvement (three days later). Serial neuroimaging studies revealed secondary fungal abscess formation at the site of hemorrhagic infarctions, which is very rare but previously described [35]. Clinical presentations of fungal brain abscess may not be specific and primarily depends on the site of involvement, single versus multiple lesions and pathological processes (angioinvasion, thrombosis or hemorrhage) [19]. The most common manifestations of fungal CNS infections include fever, nausea, vomiting, altered mental status (confusion, lethargy or loss of consciousness), seizure, focal neurological deficits, tremor, and ataxia [24]. Symptoms may progress rapidly in severely immunocompromised hosts.

Data regarding mixed mold infections are somewhat lack in the literature. Based on the most recent report by Magira et al., Aspergillus spp. was the most prevalent type of identified mixed mold infection in 27 patients retrospectively studied. The most common reported combinations were A. fumigatus/A. terreus, and A. terreus/A. niger, with the mortality rate in such infections being as high as 70% [36]. Mixed mold infection is an infrequent phenomenon, representing a diagnostic and treatment challenge, especially in immunocompromised hosts. There are limited data in the literature about the combination of A. fumigatus/ A. niger in children with vital organ involvement. The definitive diagnosis of CNS aspergillosis requires a high index of suspicion and an aggressive approach. We present herein a case of mixed A. fumigatus/ A. niger infection with fatal outcome in a patient with ALL. Given the different AF susceptibility patterns, identification of the Aspergillus at the species level should considered in invasive fungal infections with multiple site involvement. In line with the current ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline, consideration of different AF classes for the treatment of bIFIs in the patients receiving amphotericin B warranted.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- AF:

-

Antifungal

- ALL:

-

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- bIFI:

-

Breakthrough invasive fungal infection

- WBC:

-

White blood cell count

- GM:

-

Galactomannan

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ANC:

-

Absolute neutrophil count

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus infections

- IA:

-

Invasive aspergillosis

- AMOC:

-

Amir medical oncology center

References

Almutairi BM, Nguyen TB, Jansen GH, Asseri AH. Invasive aspergillosis of the brain: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29(2):375–9.

Badiee P, Hashemizadeh Z, Ramzi M, Karimi M, Mohammadi R. Non-invasive methods to diagnose fungal infections in pediatric patients with hematologic disorders. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2016;9(11):e41573.

Dotis J, Iosifidis E, Roilides E. Central nervous system aspergillosis in children: a systematic review of reported cases. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11(5):381–93.

Marzolf G, Sabou M, Lannes B, Cotton F, Meyronet D, Galanaud D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of cerebral aspergillosis: imaging and pathological correlations. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152475.

Pagano L, Ricci P, Montillo M, Cenacchi A, Nosari A, Tonso A, et al. Localization of aspergillosis to the central nervous system among patients with acute leukemia: report of 14 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(3):628–30.

Schwartz S. Cerebral Aspergillus Infections and Meningitis. In: Comarú PA, editor. Aspergillosis: from diagnosis to prevention. Berlin: Springer; 2010. p. 836.

Singh S, Chowdhury V, Dixit R. CNS aspergillosis. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2006;16(4):749.

Baddley JW. Clinical risk factors for invasive aspergillosis. Med Mycol. 2011;49(Supplement_1):S7–S12.

Jantunen E, Volin L, Salonen O, Piilonen A, Parkkali T, Anttila V-J, et al. Central nervous system aspergillosis in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31(3):191.

Torre-Cisneros J, Lopez OL, Kusne S, Martinez AJ, Starzl TE, Simmons RL, et al. CNS aspergillosis in organ transplantation: a clinicopathological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(2):188–93.

Walsh TJ, Pappas P, Winston DJ, Lazarus HM, Petersen F, Raffalli J, et al. Voriconazole compared with liposomal amphotericin B for empirical antifungal therapy in patients with neutropenia and persistent fever. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):225–34.

Glass NL, Donaldson GC. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61(4):1323–30.

Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S, Denning DW, Groll AH, Lagrou K, et al. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:e1–e38.

Lamoth F, Chung SJ, Damonti L, Alexander BD. Changing epidemiology of invasive mold infections in patients receiving azole prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(11):1619–21.

Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Breakthrough invasive mold infections in the hematology patient: current concepts and future directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(10):1621–30.

Tverdek FP, Heo ST, Aitken SL, Granwehr B, Kontoyiannis DP. Real-life assessment of the safety and effectiveness of the new tablet and intravenous formulations of posaconazole in the prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections via analysis of 343 courses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(8):e00188–17.

Auberger J, Lass-Flörl C, Aigner M, Clausen J, Gastl G, Nachbaur D. Invasive fungal breakthrough infections, fungal colonization and emergence of resistant strains in high-risk patients receiving antifungal prophylaxis with posaconazole: real-life data from a single-Centre institutional retrospective observational study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(9):2268–73.

Biehl LM, Vehreschild JJ, Liss B, Franke B, Markiefka B, Persigehl T, et al. A cohort study on breakthrough invasive fungal infections in high-risk patients receiving antifungal prophylaxis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(9):2634–41.

Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ, Perfect J, Ullmann AJ, Walsh TJ, et al. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(4):348–59.

Corzo-León DE, Satlin MJ, Soave R, Shore TB, Schuetz AN, Jacobs SE, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of invasive fungal infections in allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients in the era of antifungal prophylaxis: a single-Centre study with focus on emerging pathogens. Mycoses. 2015;58(6):325–36.

Kuster S, Stampf S, Gerber B, Baettig V, Weisser M, Gerull S, et al. Incidence and outcome of invasive fungal diseases after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a Swiss transplant cohort study. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20(6):e12981.

Lerolle N, Raffoux E, Socie G, Touratier S, Sauvageon H, Porcher R, et al. Breakthrough invasive fungal disease in patients receiving posaconazole primary prophylaxis: a 4-year study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(11):O952–O9.

Pagano L, Caira M, Candoni A, Aversa F, Castagnola C, Caramatti C, et al. Evaluation of the practice of antifungal prophylaxis use in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia: results from the SEIFEM 2010-B registry. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(11):1515–21.

Winston DJ, Bartoni K, Territo MC, Schiller GJ. Efficacy, safety, and breakthrough infections associated with standard long-term posaconazole antifungal prophylaxis in allogeneic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(4):507–15.

Pang K-AP, Godet C, Fekkar A, Scholler J, Nivoix Y, Letscher-Bru V, et al. Breakthrough invasive mould infections in patients treated with caspofungin. J Inf Secur. 2012;64(4):424–9.

Meis JF, Chowdhary A, Rhodes JL, Fisher MC, Verweij PE. Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2016;371(1709):20150460.

Alborzi A, Moeini M, Haddadi P. Antifungal susceptibility of the Aspergillus species by Etest and CLSI reference methods. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(7):429–32.

Badiee P, Moghadami M, Rozbehani H. Comparing immunological and molecular tests with conventional methods in diagnosis of acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2016;10(01):90–5.

Badiee P, Alborzi A, Shakiba E, Ziyaeyan M, Pourabbas B. Molecular diagnosis of Aspergillus endocarditis after cardiac surgery. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58(2):192–5.

Badiee P, Gandomi B, Sabz G, Khodami B, Choopanizadeh M, Jafarian H. Evaluation of nested PCR in diagnosis of fungal rhinosinusitis. Iran J Microbiol. 2015;7(1):62.

Arvanitis M, Anagnostou T, Mylonakis E. Galactomannan and polymerase chain reaction–based screening for invasive aspergillosis among high-risk hematology patients: a diagnostic meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(8):1263–72.

Gautier M, Normand A-C, L'Ollivier C, Cassagne C, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Dubus J-C, et al. Aspergillus tubingensis: a major filamentous fungus found in the airways of patients with lung disease. Sabouraudia. 2016;54(5):459–70.

Frías-De-León MG, Rosas-de Paz E, Arenas R, Atoche C, Duarte-Escalante E, de Soschin DM, et al. Identification of Aspergillus tubingensis in a primary skin infection. J Mycol Med. 2018;28(2):274–8.

Economides MP, Ballester LY, Kumar VA, Jiang Y, Tarrand J, Prieto V, et al. Invasive mold infections of the central nervous system in patients with hematologic cancer or stem cell transplantation (2000–2016): uncommon, with improved survival but still deadly often. J Inf Secur. 2017;75(6):572–80.

Pasqualotto AC, editor. Aspergillosis: from diagnosis to prevention. Berlin: Springer; 2010.

Magira EE, Jiang Y, Economides M, Tarrand J, Kontoyiannis DP. Mixed mold pulmonary infections in haematological cancer patients in a tertiary care cancer Centre. Mycoses. 2018;61(11):861–7.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to our oncologist team Dr. Shahriari, Dr. Zareifar, Dr. Zekavat and Dr. Bordbar; Salma Mehrangiz (infection control unit staff), Khaje Somaye (microbiology department staff), all members of infection control team in AMOC, for their technical support and assistance with the implementation of ASP in AMOC. Our gratitude also goes to Dr. Hassan Khajehei, for careful linguistic editing of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no support or funding to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study concept and design: AA; Acquisition of data: AA, BP; Neurosurgical intervention: MMS; Radiological advisor: LM; Mycological analysis: BP, JH, GF; Analysis and interpretation of data: AA, BP; Drafting of the manuscript: AA, BP, BH; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AA, BP. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee approved the study protocol at Prof. Alborzi Clinical Microbiology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents o for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Amanati, A., Lotfi, M., Masoudi, M. et al. Cerebral and pulmonary aspergillosis, treatment and diagnostic challenges of mixed breakthrough invasive fungal infections: case report study. BMC Infect Dis 20, 535 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05162-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05162-9