Abstract

Background

Neurogenic pulmonary edema is a rare but serious complication of febrile status epilepticus in children. Comprehensive screening for viral pathogens is seldomly performed in the work-up of febrile children.

Case presentation

A 22-month-old girl presented with her first episode of febrile status epilepticus, after which she developed acute pulmonary edema and respiratory failure. After the termination of seizure activity, the patient was intubated and managed on mechanical ventilation in the emergency room. The resolution of respiratory failure, as well as the neurological recovery, was achieved 9 h after admission, and the patient was discharged 6 days after admission without any complications. Molecular biological diagnostic methods identified the presence of human coronavirus HKU1, influenza C virus, and human parainfluenza virus 2 from the patient’s nasopharyngeal specimens.

Conclusions

Neurogenic pulmonary edema following febrile status epilepticus was suspected to be the etiology of our patient’s acute pulmonary edema and respiratory failure. Timely seizure termination and rapid airway and respiratory intervention resulted in favorable outcomes of the patient. Molecular biological diagnostic methods identified three respiratory viruses; however, their relevance and association with clinical symptoms remain speculative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Neurogenic pulmonary edema (NPE) is characterized by the development of pulmonary edema within minutes to hours of a significant central nervous system (CNS) insult, often resolving spontaneously within 24–48 h [1,2,3]. Febrile seizures (FS) is the most common convulsive event, affecting 2–5% of children younger than 60 months [4,5,6,7]. The majority of FS cases follow a benign clinical course; however, approximately 5–8% of FS cases develop status epilepticus (SE) [8, 9]. NPE following febrile SE in children is a rare complication, although its incidence rate might be underestimated [10,11,12,13].

Molecular biological diagnostic methods such as multiplex PCR and next generation sequencing (NGS) can detect pathogens from clinical specimens with high sensitivity; this also leads to co-detection of multiple pathogens from the same clinical specimen. With the increased application of multiplex PCR in clinical settings, there have been reports of multiple pathogen co-detection rates from 10 to 50% of human respiratory specimens [14,15,16,17]. It has also been revealed that multiple pathogens, both viral and bacterial, are prevalent even in respiratory specimens from healthy, asymptomatic children [14, 18]. It is sometimes difficult to interpret clinical relevance of detected pathogens by molecular biological diagnostic methods alone [19]. The interaction among co-detected multiple pathogens and their association with clinical symptoms remain controversial [17, 20,21,22,23].

We report the case of a 22-month-old girl with febrile SE who developed acute respiratory failure due to NPE. We also describe the co-detection of three respiratory viruses from the patient’s nasopharyngeal specimens using molecular biological diagnostic methods.

The Institutional Medical Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases and the Ethics Committee of Showa General Hospital approved this study (Approval Nos. 553 and 677, and REC-094, respectively). The patient’s parents provided written informed consent for analysis of the patient’s clinical specimens and publication of this case report.

Case presentation

The patient is a previously healthy 22-month-old girl without perinatal abnormalities or personal or family history of seizure. The patient had not been to any nursery school prior to the event. She had two siblings, 11 and 5 years old, who had no respiratory symptoms. Clonic seizure of the patient’s right side commenced 12 h after fever development, followed by generalized tonic and tonic-clonic seizures without self-resolution. The seizure activity had persisted for 40 min when the patient arrived at our emergency room (ER) by ambulance. Spontaneous breathing was absent with SpO2 of 50% upon ER arrival. Bag valve mask (BVM) ventilation supplied with 100% oxygen was commenced immediately, and SpO2 increased to 92%. The seizure activity was terminated by intravenous administration of 0.2 mg/kg of midazolam and 2 μg/kg of fentanyl. Her vital signs upon seizure termination were as follows: Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 3 (eyes 1, verbal 1, motor 1), pupils 3 mm in diameter and reactive to light stimuli bilaterally, body temperature 38.2 °C, heart rate 185 beats per minute (bpm), systolic blood pressure 107 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure 60 mmHg, and SpO2 99% under BVM ventilation with 100% oxygen supplementation. The patient remained apneic, and SpO2 quickly dropped to 50% when BVM ventilation was temporally interrupted. Venous blood gas analysis revealed respiratory and metabolic acidosis. An endotracheal tube of 4 mm in diameter was inserted for airway protection. Copious pink frothy airway secretions were identified upon intubation, and the discharge continued until the application of mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 6 cmH2O. SpO2 was maintained above 95% after introduction of mechanical ventilation. There were no apparent injuries or hemorrhage in the oral and nasopharyngeal cavities, nor was there laryngeal edema or airway obstruction.

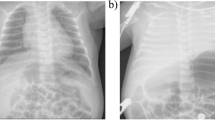

Chest auscultation revealed bilateral coarse crackles, but no heart murmur was detected. An abdominal examination revealed no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. Chest radiography showed bilateral, centrally distributed opacities without cardiac dilation (Fig. 1a). Echocardiography demonstrated normal cardiac wall motion with ejection fraction of 69% and non-pathological trivial tricuspid regurgitation. An electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia of 151 bpm without significant ST-T changes, atrial overload, or ventricular hypertrophy. Laboratory examinations revealed a mildly elevated white blood cell count, hyperglycemia, hyperammonemia, acidemia, hypercapnia, and lactic acidosis (Table 1). Creatine kinase (CK), platelet count and coagulation times were within normal limits. Computed tomography (CT) of the head revealed no abnormal findings, and continuous electroencephalography (EEG) findings did not suggest encephalopathy. A cerebrospinal fluid examination revealed no elevation in cell counts. Rapid immunochromatographic tests of nasopharyngeal specimen for influenza A and B viruses were negative.

Hypercapnia resolved after introduction of mechanical ventilation, and SpO2 was maintained above 95% with PEEP of 6 cmH2O and FiO2 of 0.3 or less. Pink frothy airway secretions persisted for 6 h after endotracheal intubation and then spontaneously resolved. Intravenous administration of 300 mg/kg/day of ampicillin/sulbactam (ABPC/SBT) and 20mf/kg/day of acyclovir (ACV) were empirically initiated. The patient was managed under continuous infusion of midazolam and EEG monitoring. There was no recurrence of seizure activity, and the patient became responsive without apparent neurological deficit nine hours after admission. The midazolam infusion was terminated, and the patient was extubated uneventfully 10 h after admission. There was no sign of respiratory distress after extubation, and the oxygen therapy was terminated when improvement of chest radiograph findings was confirmed on hospital day 2 (Fig. 1b). Blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and urine cultures were all negative for bacteria. Tracheal secretion cultures were positive for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, although the patient revealed no sign of bacterial pneumonia. Real-time PCR analysis did not reveal herpes simplex virus in cerebrospinal fluid, or human herpesviruses 6 and 7 in serum. ABPC/SBT and ACV were terminated on hospital day 6, and the patient was discharged. The follow-up EEG examination at one month after discharge was normal and the patient remained free of complications.

Molecular biological diagnostic assays were conducted for comprehensive detection of viral pathogens from the patient’s nasopharyngeal specimens collected upon admission and on hospital day 2. The BIOFIRE FILMARRAY Respiratory Panel (bioMérieux, France) and real-time RT-PCR were used to target predefined respiratory pathogens, and metagenomic RNA-Seq using NGS was performed to detect pathogens in unbiased fashion (Table 2) [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. The BIOFIRE FILMARRAY Respiratory Panel (BioMérieux, France) does not targeting influenza C virus (FluC), however, it detected human coronavirus HKU1 (hCoV-HKU1) and human parainfluenza virus 2 (HPIV2) from the initial specimen. Real-time RT-PCR is an assay targeting 19 respiratory viruses including FluC. It identified hCoV-HKU1, FluC, and HPIV2 with quantification cycles (Cq) values of 21.5, 19.7, and 36.4, respectively. The following respiratory pathogens were not detected by BIOFIRE FILMARRAY Respiratory Panel or by real-time RT-PCR assay; influenza A (subtype H1pdm and H3), influenza B, human metapneumovirus, human respiratory syncytial viruses A and B, human bocavirus, rhinovirus, human respiroviruses 1 and 3, human parainfluenza virus 4, human adenoviruses (including 2 and 4), human coronaviruses NL63, OC43, and 229E, Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. NGS revealed hCoV-HKU1 and FluC, but HPIV2 was not identified. A nasopharyngeal specimen collected on hospital day 2 was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR, revealing hCoV-HKU1 and FluC with Cq values of 30.0 and 25.9, respectively, but HPIV2 was not detected.

Discussion and conclusions

We report the pediatric NPE case following febrile SE, in whom three respiratory viruses were co-detected from the patient’s nasopharyngeal specimens using molecular biological diagnostic methods. NPE following febrile SE in children is a rare but serious life-threatening complication [11,12,13]. Despite the higher incidence rate of FS in Japanese children than in children in other countries, few Japanese patients with NPE caused by febrile SE have been reported in literature [31,32,33].

NPE was suspected to be the etiology of our patient’s acute respiratory failure. Pulmonary edema was diagnosed by pink frothy airway secretions. There was prolonged oxygenation failure, even after resolution of the SE-induced apnea, with bilateral coarse crackles upon auscultation, and characteristic chest radiograph findings.

NPE is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion. The echocardiography revealed intact cardiac function, and electrocardiogram and CK measurement revealed no evidence of myocardial injury. Intravenous volume resuscitation was not conducted prior to the presentation of pulmonary edema. These findings rule out the possibility of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. The absence of airway obstruction upon intubation makes the negative pressure pulmonary edema an unlikely etiology. Viral, bacterial, and aspiration pneumoniae, as well as acute respiratory distress syndrome, do not fit the clinical presentation of respiratory failure with rapid development and resolution. The absence of hemorrhagic injury in the oral and nasopharyngeal cavities excludes the possibility of blood aspiration.

Our case has some limitations regarding the diagnosis of NPE. Arterial blood gas measurement was not conducted because of the avoidance of arterial catheter insertion in pediatric patients in our facility. This prevented us from evaluating respiratory function indices such as PaO2/FiO2 ratio and alveolar-arterial gradient. The more specific markers of myocardial injury and volume overload were not measured, including creatine kinase-muscle/brain, cardiac troponin, and brain natriuretic peptide. Despite these limitations, exclusion of other common etiologies led us to assume that NPE following SE was the most likely etiology of our patient’s acute respiratory failure.

The pathophysiology of NPE remains unclear; however, a massive increase in sympathetic activity following CNS insult is thought to be the major initial factor [1,2,3]. The hypothalamus and medulla are thought to be the anatomical origins of NPE, and the identified triggers of NPE include enterovirus-71-associated brainstem encephalitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, and epilepsy with generalized seizures or SE [2, 34]. It is hypothesized that sympathetic overstimulation leads to generalized vasoconstriction, resulting in pulmonary hypertension and increased pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressure [35]. The increased permeability of pulmonary capillaries is suspected to be another mechanism of NPE, which can be attributed to the stimulation of alpha- or beta-adrenergic receptors by sympathetic overactivity, as well as to the release of cytokines by triggering cerebral lesions [1, 2, 35, 36]. The management of NPE includes rapid cessation or alleviation of CNS insult and supportive treatment of pulmonary edema. In our case, febrile SE was rapidly terminated upon hospital arrival, and oxygenation was secured by introduction of positive pressure mechanical ventilation. Timely achievement of both resulted in the favorable outcome of our patient.

Three respiratory viruses were identified from our patient’s nasopharyngeal specimens; hCoV-HKU1, FluC, and HPIV2. HCoV-HKU1 mainly causes upper respiratory tract infection, and higher incidence of FS complication is reported compared to other respiratory viruses [37, 38]. Acute upper respiratory tract infection caused by FluC is often accompanied by mild symptoms; however, there are reports of severe pneumonia and acute encephalopathy in children [39,40,41]. HPIV2 causes lower respiratory tract infection, and it is responsible for the majority of viral croup cases together with HPIV type 1 [42,43,44].

Our findings regarding pathogens using molecular diagnostic methods requires cautious interpretation. Genomic detection by molecular biological diagnostic methods do not certify the viability or pathogenicity of detected pathogens [18, 19]. It can be difficult to distinguish whether the infection of detected pathogen is symptomatic or asymptomatic, especially when several pathogens are co-detected, even from healthy, asymptomatic individuals [14, 18]. The viral loads obtained from real-time RT-PCR assay can be influenced by individual clinical specimens’ collection methods. Viral load standardization by reference genes in clinical specimens is not established, prohibiting comparing viral loads among various clinical samples. It is proposed, however, that pathogens with high viral loads are likely to be significantly associated with respiratory infections [45]. The real-time RT-PCR analysis upon consecutively collected clinical specimens during symptomatic periods, or upon samples from both symptomatic and asymptomatic periods, might help elucidate the clinical significance of detected pathogens.

The clinical relevance of the three detected viruses in our patient remains speculative. The finding of high viral loads of hCoV-HKU1 and FluC in the initial specimen upon admission suggests that hCoV-HKU1 and FluC were associated with the patient’s clinical presentation. The initial low viral load and the later disappearance of HPIV2 might have resulted from either HPIV2 infection prior to the other two viruses or asymptomatic colonization in the patient’s nasopharyngeal cavity. Considering the absence of nursey school attendance, the three respiratory viruses might have been transmitted to the patient from her older siblings. Symptomatically, it is also assumed that hCoV-HKU1 and FluC were associated with the pathogenesis of our patient’s case. Although human coronavirus is associated with various clinical presentations including acute bronchiolitis and gastroenteritis, its etiological role is most likely in pediatric FS cases [46]. HCoV-HKU1 is significantly associated with pediatric FS cases, even among human coronaviruses, which makes hCoV-HKU1 most likely responsible for our patient’s FS and NPE following the CNS insult [38]. There remains a possibility of the contribution of FluC to our patient’s clinical presentation, considering a case report of acute encephalopathy with FluC infection [41].

Interaction of multiple viral pathogens and their association with clinical symptoms remain controversial. Both negative and positive correlations between virus co-detection and clinical symptoms have been reported [20,21,22,23]. Tanner et al. suggested that the co-detection of different respiratory viruses is not random but reciprocal, either positively or negatively [17]. Regarding human coronavirus, the presence of viral co-detection was associated with an increased likelihood of lower respiratory tract disease compared to the detection of coronavirus alone [20]. This suggests the possibility that human coronavirus might demonstrate higher pathogenicity when co-existing with other viral pathogens. It cannot be determined, however, whether interaction among co-detected three respiratory pathogens contributed to the rare and severe clinical presentation of our patient.

We described a pediatric case of NPE following febrile status epilepticus. The timely termination of seizure activity and the rapid introduction of positive pressure mechanical ventilation resulted in the patient’s favorable outcome. Three respiratory viruses were identified using molecular biological diagnostic methods. Nevertheless, the clinical significance of these findings remains speculative.

Abbreviations

- ABPC/SBT:

-

Ampicillin/sulbactam

- ACV:

-

Acyclovir

- BVM:

-

Bag valve mask

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalogram

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- hCoV-HKU1:

-

Human coronavirus HKU1

- HPIV2:

-

Human parainfluenza virus 2

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

- NPE:

-

Neurogenic pulmonary edema

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

- PICU:

-

Pediatric intensive care unit

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SE:

-

Status epilepticus

References

Busl KM, Bleck TP. Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(8):1710–5.

Davison DL, Terek M, Chawla LS. Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Crit Care. 2012;16(2):212.

Baumann A, Audibert G, McDonnell J, Mertes PM. Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(4):447–55.

Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures; American Academy of Pediatrics. Neurodiagnostic evaluation of the child with a simple febrile seizure. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):389–94.

Natsume J, Hamano SI, Iyoda K, et al. New guidelines for management of febrile seizures in Japan. Brain Dev. 2017;39(1):2–9.

Verity CM, Butler NR, Golding J. Febrile convulsions in a national cohort followed up from birth. II--Medical history and intellectual ability at 5 years of age. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290(6478):1311–5.

Hesdorffer DC, Benn EK, Bagiella E, Nordli D, Pellock J, Hinton V. Shinnar S; FEBSTAT study team. Distribution of febrile seizure duration and associations with development. Ann Neurol. 2011 Jul;70(1):93–100.

Shinnar S. Febrile seizures and mesial temporal sclerosis. Epilepsy Curr. 2003;3(4):115–8.

Gurcharran K, Grinspan ZM. The burden of pediatric status epilepticus: epidemiology, morbidity, mortality, and costs. Seizure. 2019;68:3–8.

Mahdavi Y, Surges R, Nikoubashman O, Olaciregui Dague K, Brokmann JC, Willmes K, Wiesmann M, Schulz JB, Matz O. Neurogenic pulmonary edema following seizures: a retrospective computed tomography study. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;94:112–7.

Nguyen TT, Hussain E, Grimason M, Goldstein J, Wainwright MS. Neurogenic pulmonary edema and acute respiratory distress syndrome in a healthy child with febrile status epilepticus. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(10):1287–91.

Aneja A, Arora N, Sanjeev R, Semalti K. Neurogenic pulmonary edema following status Epilepticus: an unusual case. Int J Clin Ped. 2015;4(4):186–8.

Reuter-Rice K, Duthie S, Hamrick J. Neurogenic pulmonary edema associated with pediatric status epilepticus. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(10):957–8.

Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) Study Group. Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet. 2019;394(10200):757–79.

Wong-Chew RM, García-León ML, Noyola DE, et al. Respiratory viruses detected in Mexican children younger than 5 years old with community-acquired pneumonia: a national multicenter study. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;62:32–8.

El Kholy AA, Mostafa NA, Ali AA, Soliman MM, El-Sherbini SA, Ismail RI, El Basha N, Magdy RI, El Rifai N, Hamed DH. The use of multiplex PCR for the diagnosis of viral severe acute respiratory infection in children: a high rate of co-detection during the winter season. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(10):1607–13.

Tanner H, Boxall E, Osman H. Respiratory viral infections during the 2009-2010 winter season in Central England, UK: incidence and patterns of multiple virus co-infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(11):3001–6.

Morikawa S, Hiroi S, Kase T. Detection of respiratory viruses in gargle specimens of healthy children. J Clin Virol. 2015;64:59–63.

Gray J, Coupland LJ. The increasing application of multiplex nucleic acid detection tests to the diagnosis of syndromic infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(1):1–11.

Ogimi C, Englund JA, Bradford MC, Qin X, Boeckh M, Waghmare A. Characteristics and outcomes of coronavirus infection in children: the role of viral factors and an Immunocompromised state. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019;8(1):21–8.

Gagliardi TB, Paula FE, Iwamoto MA, Proença-Modena JL, Santos AE, Camara AA, Cervi MC, Cintra OA, Arruda E. Concurrent detection of other respiratory viruses in children shedding viable human respiratory syncytial virus. J Med Virol. 2013;85(10):1852–9.

Trenholme AA, Best EJ, Vogel AM, Stewart JM, Miller CJ, Lennon DR. Respiratory virus detection during hospitalisation for lower respiratory tract infection in children under 2 years in South Auckland, New Zealand. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(6):551–5.

Upadhyay BP, Banjara MR, Shrestha RK, Tashiro M, Ghimire P. Etiology of Coinfections in children with influenza during 2015/16 winter season in Nepal. Int J Microbiol. 2018;2018:8945142.

Kaida A, Kubo H, Takakura K, Sekiguchi J, Yamamoto SP, Kohdera U, Togawa M, Amo K, Shiomi M, Ohyama M, Goto K, Hase A, Kageyama T, Iritani N. Associations between co-detected respiratory viruses in children with acute respiratory infections. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2014;67(6):469–75.

Nakauchi M, Takayama I, Takahashi H, Oba K, Kubo H, Kaida A, Tashiro M, Kageyama T. Real-time RT-PCR assays for discriminating influenza B virus Yamagata and Victoria lineages. J Virol Methods. 2014;205:110–5.

Nakauchi M, Yasui Y, Miyoshi T, Minagawa H, Tanaka T, Tashiro M, Kageyama T. One-step real-time reverse transcription-PCR assays for detecting and subtyping pandemic influenza a/H1N1 2009, seasonal influenza a/H1N1, and seasonal influenza a/H3N2 viruses. J Virol Methods. 2011;171(1):156–62.

Poritz MA, Blaschke AJ, Byington CL, Meyers L, Nilsson K, Jones DE, Thatcher SA, Robbins T, Lingenfelter B, Amiott E, Herbener A, Daly J, Dobrowolski SF, Teng DH, Ririe KM. FilmArray, an automated nested multiplex PCR system for multi-pathogen detection: development and application to respiratory tract infection. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26047.

Abayasekara LM, Perera J, Chandrasekharan V, Gnanam VS, Udunuwara NA, Liyanage DS, Bulathsinhala NE, Adikary S, Aluthmuhandiram JVS, Thanaseelan CS, Tharmakulasingam DP, Karunakaran T, Ilango J. Detection of bacterial pathogens from clinical specimens using conventional microbial culture and 16S metagenomics: a comparative study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):631.

Kuroda M. Next-generation sequencing protocol for comprehensive detection of pathogens. Database of Pathogen Genomics and Epidemiology provided by National Institute of Infectious Diseases https://gph.niid.go.jp/gs_app/ngs_sop_draft_ver1.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2020.

Takeuchi F, Sekizuka T, Yamashita A, Ogasawara Y, Mizuta K, Kuroda M. MePIC, metagenomic pathogen identification for clinical specimens. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2014;67(1):62–5.

Choi YJ, Jung JY, Kim JH, Kwon H, Park JW, Kwak YH, Kim DK, Lee JH. Febrile seizures: are they truly benign? Longitudinal analysis of risk factors and future risk of afebrile epileptic seizure based on the national sample cohort in South Korea, 2002-2013. Seizure. 2019;64:77–83.

Sugai K. Current management of febrile seizures in Japan: an overview. Brain Dev. 2010;32(1):64–70.

Tasaka K, Matsubara K, Hori M, Nigami H, Iwata A, Isome K, Kawasaki Y, Nagai S. Neurogenic pulmonary edema combined with febrile seizures in early childhood-a report of two cases. IDCases. 2016;6:90–3.

Finsterer J. Neurological perspectives of neurogenic pulmonary edema. Eur Neurol. 2019;81(1–2):94–102.

Šedý J, Kuneš J, Zicha J. Pathogenetic mechanisms of neurogenic pulmonary edema. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(15):1135–45.

Avlonitis VS, Wigfield CH, Kirby JA, Dark JH. The hemodynamic mechanisms of lung injury and systemic inflammatory response following brain death in the transplant donor. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(4 Pt 1):684–93.

Jin Y, Song JR, Xie ZP, Gao HC, Yuan XH, Xu ZQ, Yan KL, Zhao Y, Xiao NG, Hou YD, Duan ZJ. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of human CoV-HKU1 in children with acute respiratory tract infections in China. J Clin Virol. 2010 Oct;49(2):126–30.

Lau SK, Woo PC, Yip CC, Tse H, Tsoi HW, Cheng VC, Lee P, Tang BS, Cheung CH, Lee RA, So LY, Lau YL, Chan KH, Yuen KY. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2063–71.

Atkinson KV, Bishop LA, Rhodes G, Salez N, McEwan NR, Hegarty MJ, Robey J, Harding N, Wetherell S, Lauder RM, Pickup RW, Wilkinson M, Gatherer D. Influenza C in Lancaster, UK, in the winter of 2014-2015. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46578.

Thielen BK, Friedlander H, Bistodeau S, Shu B, Lynch B, Martin K, Bye E, Como-Sabetti K, Boxrud D, Strain AK, Chaves SS, Steffens A, Fowlkes AL, Lindstrom S, Lynfield R. Detection of influenza C viruses among outpatients and patients hospitalized for severe acute respiratory infection, Minnesota, 2013-2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7):1092–8.

Takayanagi M, Umehara N, Watanabe H, Kitamura T, Ohtake M, Nishimura H, Matsuzaki Y, Ichiyama T. Acute encephalopathy associated with influenza C virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(6):554.

Henrickson KJ. Parainfluenza viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(2):242–64.

Mizuta K, Abiko C, Aoki Y, Ikeda T, Itagaki T, Katsushima F, Katsushima Y, Matsuzaki Y, Noda M, Kimura H, Ahiko T. Epidemiology of parainfluenza virus types 1, 2 and 3 infections based on virus isolation between 2002 and 2011 in Yamagat, Japna. Microbiol Immunol. 2012;56(12):855–8.

Leung AK, Kellner JD, Johnson DW. Viral croup: a current perspective. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18(6):297–301.

Schjelderup Nilsen HJ, Nordbø SA, Krokstad S, Døllner H, Christensen A. Human adenovirus in nasopharyngeal and blood samples from children with and without respiratory tract infections. J Clin Virol. 2019;111:19–23.

Jevšnik M, Steyer A, Pokorn M, Mrvič T, Grosek Š, Strle F, Lusa L, Petrovec M. The role of human coronaviruses in children hospitalized for acute bronchiolitis, acute gastroenteritis, and febrile seizures: a 2-year prospective study. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155555.

Acknowledgements

None.

Availability of data and material

All the data generated and analyzed in this study are described in this published article.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (Grant Nos: JP18fk0108030, JP18fk0108019). The funding agency played no roles in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SE, KH, SA, YI, TK1, TS, TK2, and KO contributed to the clinical treatment. MH and MK performed Filmarray and NGS. SS, TO and TK3 performed real-time RT-PCR. YT, TI, KO and TK3 wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional medical ethical committees of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (Approval No. 553 and 677) in Japan, the ethical committee of Showa General Hospital (Approval No. REC-094) and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents regarding the use of the patient’s clinical specimens for genomic analysis.

Consent for publication

The written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents regarding the publication of this manuscript. The consent form is held by the authors’ institution and is available for review upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Takagi, Y., Imamura, T., Endo, S. et al. Neurogenic pulmonary edema following febrile status epilepticus in a 22-month-old infant with multiple respiratory virus co-detection: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 20, 388 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05115-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05115-2