Abstract

Background

Mycoplasma sp. are well recognized as etiological agents of respiratory and sexually transmitted disease. Mycoplasma penetrans, a species of Mycoplasma sp., has been frequently detected in HIV-positive patients and associated with the progression of HIV-associated disease. To date, there is only a single case report describing M. penetrans as the causative agent of a severe respiratory tract infection in a HIV-negative patient.

Case presentation

In this report, we describe the case of M. penetrans bacteremia in a HIV-negative, 38-year-old, female, immunocompromised, solid organ transplant patient (combined kidney and pancreas transplantation in 2016), who was admitted to our hospital with anemic uterine bleeding and fever of 38.3 °C. Several hours before her admission at our university hospital, a latex bladder catheter was inserted into her uterus and she complained about fatigue, dizziness and ongoing vaginal bleeding. Laboratory examination showed severe anemia, but microbiological examination was inconspicuous (culture negative vaginal and cervical smears, negative urine culture). Bacterial blood cultures showed a growth signal after 4 h, but microscopic examination with Gram staining and subcultures on different agar media did not identify bacterial pathogens. To identify the bacterial cause of malignancy in the patient, metagenomic sequencing of the blood culture was performed that identified M. penetrans.

Conclusion

Metagenomic sequencing identified M. penetrans in an immunosuppressed patient with culture-negative bacteremia. Clinicians should be aware of the opportunistic potential of M. penetrans that may cause severe infections in certain vulnerable patient populations and the limitations of culture and Gram staining for confirming the presence of fastidious bacterial pathogens like Mycoplasma spp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mycoplasmataceae are among the smallest self-replicating organisms known and the only described prokaryotes that lack a cell wall [1]. They have an extremely reduced genome size of around 1 Mb and lack most genes required for nutrient metabolism and therefore often adopt a parasitic lifestyle in their host organisms. Mycoplasmataceae have been isolated from various body sites in humans; however, only a few species have been well recognized as etiological agents of disease [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Among these the most prevalent pathogenic Mycoplasma spp. in humans are Mycoplasma pneumoniae that causes respiratory tract infections and pneumonia, and the widespread sexually transmitted Mycoplasma genitalium. Mycoplasma hominis and the closely related species Ureaplasma urealyticum are common colonizers of the urogenital tract and have been associated with chronic urogenital infections [9, 10].

For the detection of bacterial pathogens in patients with bacteremia, blood culture is still the most commonly used diagnostic method in the bacteriology laboratory. However, culture and Gram staining often remain negative when fastidious, cell-wall free microorganisms such as Mycoplasma spp. are the causative agent of infection. Therefore, rapid detection of microorganisms is pivotal for patient management and initiation of adequate antimicrobial therapy. In cases in which blood culture remains negative but the clinical signs and symptoms of the patient strongly indicates infectious disease, diagnosis can be achieved by using metagenomic sequencing. Metagenomics allows culture-independent sequencing of the pathogen’s genome directly from the clinical specimens and potentially provides insights into the pathogen’s virulence (by detection of virulence genes) and drug susceptibility (by identification of resistance mutations in target genes).

Case presentation

In June 2018, a 38-year-old female patient was admitted to our hospital with anemic uterine bleeding and fever of 38.3 °C (Fig. 1). Her personal history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus type I, a combined kidney and pancreas transplantation in 2016 and known uterine myomas, which were the origin of several episodes of hemorrhagic bleeding within the last 2 years. The nulliparous patient was in regular gynecological examination without surgical interventions. She was denied implantation of any levonorgestrel containing intrauterine device because of concerns about elevated risk of foreign-body associated infection in her immunocompromised state (dual immunosuppression with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil; both with stable drug levels).

Upon admission at our university hospital, the patient complained about fatigue, dizziness and ongoing vaginal bleeding. Several hours before admission, a latex bladder catheter was inserted into her uterus, and she received an intravenous hemostatic treatment with tranexamic acid and fibrinogen in another hospital. On examination, the patient was in a reduced general condition but alert and fully oriented. The temperature was 38.3 °C, the blood pressure 107/45 mmHg, the pulse 90 beats per minute, and the respiratory rate and oxygen saturation were in normal range.

Laboratory examination showed severe anemia (hemoglobin 40 g/L, hematocrit 0.137 L/L, erythrocyte count [1.37 × 1012/L]) but normal leucocyte (4.38 × 109/L) and thrombocyte counts (193 × 109/L). C-reactive protein was in a normal range (3.3 mg/L).

A microbiological diagnostic workup was undertaken. The vaginal smear grew normal flora and Staphylococcus aureus. The cervical smear was PCR-negative for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. Two out of four blood culture bottles turned positive after 5 h (Bact/Alert® Virtuo, BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France). However, microscopy with Gram stain showed no microorganisms, and subcultures on different agar media (i.e. Columbia sheep blood agar, colistin-nalidixic acid agar, chocolate agar, MacConkey agar, brucella agar, phenylethyl alcohol agar [all BioMérieux] and a modified Shepard agar medium [A7; ELITech, Puteaux, France] remained without growth. In the effort to identify the cause of the positive growth signal in the blood culture, 5 ml of the blood culture was used for metagenomic sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq platform. In detail, 2 ml erythrocyte lysis buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was added to 5 ml of negative blood culture. It was vortexed at maximum speed for 15 s and afterwards incubated for 5 min at room temperature, followed by addition of 0.1 volume of 10X Turbo DNAse buffer and 3 μl of Turbo DNAse (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc.). The sample was gently mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Afterwards, it was centrifuged at maximum speed for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed. The pellet was resuspended in 650 μl of pre-warmed PM1 buffer from the AllPrep® PowerFecal® DNA/RNA Kit (Qiagen). DNA extraction from bacterial cells was performed according to the manufactures’ instructions. Library preparation was done using the Qiagen® QIAseq FX DNA Library Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the producers’ recommendations. Sequencing library quality and size distribution were analyzed on a Fragment analyzer automated CE system (Advanced Analytical Technologies Inc., Heidelberg, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the Fragment Analyzer 474 HS NGS Fragment Kit. Sequencing libraries were paired-end sequenced (2 × 150 bp) on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina®, San Diego CA, USA).

Raw sequencing reads (FASTQ) were filtered and trimmed using TRIMMOMATIC [11], applying a threshold PHRED score of 25. Phylogenetic analysis was done by using the full length 16S rRNA, rpoB and recA gene sequences of the following Mycoplasma spp.: M. penetrans HF-2 (NCBI accession number: BA000026.2), M. genitalium G37 (NCBI accession number: NC_000908.2), M. pneumoniae M129 (NCBI accession number: NC_000912.1), Mycoplasma fermentans M64 (NCBI accession number: NC_014921.1), Mycoplasma salivarium ATCC_23064 (NCBI accession number: NZ_AXZE01000009.1), M. hominis ATCC_23114 (NCBI accession number: NC_013511.1), and as outlier U. urealyticum serovar 10 ATCC 33699 (NCBI accession number: NC_011374.1) was included in the phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic trees were generated with the FastTree MP software [12] (bootstrap 1000 option, maximum likelihood GTR [generalized time-reversible model] option). The metagenomic sequence reads covered 99.2% of the published reference sequence of 1.35862 Mb [6]. In the 16S rRNA gene, two mismatches were found at nucleotide positions C98T and T221C compared to the reference strain sequence. This combined genetic information points towards the presence of M. penetrans in the blood cultures (Fig. 2). In order to confirm the phylogenetic analysis, metagenomic sequences of the negative blood culture from the patient with a growth signal in the BacT/ALERT system were classified using Kaiju [13] and yielded 363′851 reads, of which 78% were annotated as M. penetrans (Additional file 2: Table S1, Additional file 1: Figure S1). An inoculated blood culture without a growth signal in the BacT/ALERT system and the non-inoculated blood culture growth medium were sequenced as negative controls for the meta-genomic sequencing approach (Additional file 3: Table S2, Additional file 4: Table S3). While no M. penetrans reads were identified in both negative controls, the most frequently detected reads assigned to Enterococcus sp., Streptococcus sp. and Staphylococcus sp. (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

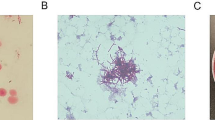

Phylogenetic analysis of clinical metagenomic reads detected by metagenomic sequencing of the negative blood culture from the patient with a growth signal in the BacT/ALERT system (i.e. clinical metagenomic reads). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the full length 16S rRNA (a), the rpoB (b) and the recA gene sequences (c) of different Mycoplasma sp. with Ureaplasma urealyticum as outlier

The patient was taken to the operating theatre for diagnostic hysteroscopy and endometrial ablation. She received a preoperative single shot dose of cefazolin (2 g) intravenously. Since the postoperative course was without complications, the patient remained afebrile and the uterine bleeding stopped after the removal of intrauterine catheter. The M. penetrans bacteremia was self-limiting, requiring no further antibiotic treatment, and the patient was discharged in stable general condition.

Discussion

In this study, we report the case of an immunocompromised 38-year-old female patient with culture negative bacteremia that most likely results from a preceding urogenital M. penetrans colonization. Previously, only a few studies have focused on bacteremia caused by urogenital Mycoplasma spp. [14, 15]. Colonization rate of M. penetrans in the urogenital tract of healthy women and men is unknown; however, M. penetrans seroprevalence was < 1% in HIV-negative blood donors [16]. In congruence, other studies confirmed a low M. penetrans seroprevalence of 0.3% in the general population [17]. In contrast, high M. penetrans seroprevalence was found in HIV-positive patients and increased with progression of HIV-associated disease [2, 17, 18]. Taken together, these findings indicate that M. penetrans seroprevalence may be associated with the immune status of the patient. However, reports on M. penetrans infection in HIV-negative individuals are scarce in the literature. To date, only a single case report exists describing the isolation of M. penetrans from a HIV-negative patient with a primary antiphospholipid syndrome, a multisystem autoimmune condition [19].

As there are substantial difficulties in detecting fastidious bacterial pathogens like M. penetrans with culture and Gram staining, we believe that there might be a significant “under-detection” of M. penetrans colonization and infection. Therefore, more rapid, culture-independent molecular methods are required to circumvent this potential detection bias. In recent years, metagenomic sequencing has proven useful in investigating the pathogenic potential of fastidious microorganisms that can just be laboriously cultivated directly from clinical specimens [20, 21]. However, use of appropriate controls is pivotal as the presence of contaminating DNA in blood cultures, extraction chemicals or sequencing reagents may lead to false interpretation of PCR-based (e.g. 16S rRNA sequencing) or meta-genomic sequencing results. One limitation of meta-genomic sequencing approaches are the still long turn-around times, and thus, meta-genomic sequencing results are often not timely available to the treating physician. This results from the fact that meta-genomic sequencing is mostly just employed when the “first-line of diagnostics” (e.g. Gram stain and culture on solid agar media) has failed. Also in this case report, meta-genomic sequencing results could just be made available to the physician after empiric cephalosporin-based therapy had been administered to the patient and the hysterectomy had been performed. Luckily, the patient cleared the bacteremia spontaneously most probably due to bacterial load reduction via hysteroscopy and improvement of her general condition, making specific antibiotic treatment (e.g. with a macrolide antibiotic) unnecessary. Thus, diagnostic workflows must be improved in order to timely provide meta-genomic sequencing results. This requires more rapid library preparation and sequencing protocols, and most of all, cheaper sequencing chemicals that enable a cost-efficient use of meta-genomic sequencing as “first-line diagnostics” in certain patient populations (e.g. critically ill patients, transplant recipients, immunocompromised patients).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the patient described in our case report is HIV-negative but immunocompromised (solid organ transplant). To our knowledge, this is the first report of M. penetrans bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient. Although we cannot track back the route of infection in the patient, we assume that the source of the bacteremia with M. penetrans was due to mucosal translocation in the utero-cervical compartment in the context of several gynecological interventions. We could show that metagenomic sequencing directly from clinical specimens in patients with culture negative bacteremia of unknown origin can be a helpful tool to receive an accurate microbiological diagnosis, thus allowing to potentially switch to a targeted antibiotic treatment and stop unnecessary empiric treatment for the purposes of antibiotic stewardship.

Availability of data and materials

Whole genome sequence of the analyzed clinical Mycoplasma penetrans isolate is available on NCBI under accession number: RCHY00000000 (BioSample: SAMN10180533).

References

Fraser CM, Gocayne JD, White O, Adams MD, Clayton RA, Fleischmann RD, Bult CJ, Kerlavage AR, Sutton G, Kelley JM. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–404.

Blanchard A. Mycoplasmas and HIV infection, a possible interaction through immune activation. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1997;109:590–3.

Clausen HF, Fedder J, Drasbek M, Nielsen PK, Toft B, Ingerslev HJ, Birkelund S, Christiansen G. Serological investigation of Mycoplasma genitalium in infertile women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1866–74.

Peterson SN, Fraser CM. The complexity of simplicity. Genome Biol. 2001;2:1–7.

Rosengarten R, Citti C, Much P, Spergser J, Droesse M, Hewicker-Trautwein M. The changing image of mycoplasmas: from innocent bystanders to emerging and reemerging pathogens in human and animal diseases. Emerg Bacterial Pathog. 2001;8:166–85 Karger Publishers.

Sasaki Y, Ishikawa J, Yamashita A, Oshima K, Kenri T, Furuya K, Yoshino C, Horino A, Shiba T, Sasaki T. The complete genomic sequence of Mycoplasma penetrans, an intracellular bacterial pathogen in humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5293–300.

Taylor-Robinson D. Mycoplasma genitalium-an up-date. London: SAGE Publications Sage UK; 2002.

Uusküla A, Kohl PK. Genital mycoplasmas, including Mycoplasma genitalium, as sexually transmitted agents. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:79–85.

Potts JM, Ward AM, Rackley RR. Association of chronic urinary symptoms in women and Ureaplasma urealyticum. Urol. 2000;55:486–9.

Baka S, Kouskouni E, Antonopoulou S, Sioutis D, Papakonstantinou M, Hassiakos D, Logothetis E, Liapis A. Prevalence of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in women with chronic urinary symptoms. Urol. 2009;74:62–6.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20.

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1641–50.

Menzel P, Ng KL, Krogh A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11257.

First MP. Mycoplasmemia in adult male patients. JAMA. 1976;236:2522–4.

Levi N, Eiberg J, Skov JJ, Prag J, Jörgensen J, Schroeder T. Mycoplasma in urine and blood following catheterisation of patients undergoing vascular surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;38:355–8.

Wang RH, Hayes MM, Wear D, Lo S, Shih JK, Alter H, Grandinetti T, Pierce P. High frequency of antibodies to Mycoplasma penetrans in HIV-infected patients. Lancet. 1992;340:1312–6.

Wang RYH, Shih JWK, Weiss SH, Grandinetti T, Pierce PF, Lange M, Alter HJ, Wear DJ, Davies CL, Mayur RK. Mycoplasma penetrans infection in male homosexuals with AIDS: high seroprevalence and association with Kaposi's sarcoma. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:724–9.

Grau O, Slizewicz B, Tuppin P, Launay V, Bourgeois E, Sagot N, Moynier M, Lafeuillade A, Bachelez H, Clauvel JP. Association of Mycoplasma penetrans with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:672–81.

Yáñez A, Cedillo L, Neyrolles O, Alonso E, Prévost M-C, Rojas J, Watson HL, Blanchard A, Cassell GH. Mycoplasma penetrans bacteremia and primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:164–7.

Seth-Smith HM, Harris SR, Skilton RJ, Radebe FM, Golparian D, Shipitsyna E, Duy PT, Scott P, Cutcliffe LT, O’Neill C. Whole-genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis directly from clinical samples without culture. Genome Res. 2013;23:855–66.

Loman NJ, Constantinidou C, Christner M, Rohde H, Chan JZ-M, Quick J, Weir JC, Quince C, Smith GP, Betley JR. A culture-independent sequence-based metagenomics approach to the investigation of an outbreak of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli O104: H4. JAMA. 2013;309:1502–10.

Acknowledgements

We thank the technicians of the Institute of Medical Microbiology for expert help and assistance. We thank the Institute of Medical Microbiology, University of Zurich, for continuous support.

Funding

This study was funded by the Institute of Medical Microbiology, University of Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BP and DV collected the patients’ health related data. FI, RVH, PMK and KW were responsible for the microbiological work-up of the samples and the data analysis. All authors wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for the use of her biological material for meta-genomic sequencing and her health-related and microbiological data for this study.

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of the case study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

(A) Metagenomic sequencing of the negative blood culture from the patient with a growth signal in the BacT/ALERT system (363′851 classified reads), (B) of an inoculated blood culture without a growth signal in the BacT/ALERT system (12′500 classified reads) and (C) of the non-inoculated blood culture growth medium (16′047 classified reads).

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Metagenomic sequencing of the negative blood culture from the patient with a growth signal in the BacT/ALERT system.

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Metagenomic sequencing of an inoculated blood culture without a growth signal in the BacT/ALERT system.

Additional file 4: Table S3.

Metagenomic sequencing of the non-inoculated blood culture growth medium.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Preiswerk, B., Imkamp, F., Vorburger, D. et al. Mycoplasma penetrans bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient detected by metagenomic sequencing: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 20, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4723-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4723-7