Abstract

Background

An infected aneurysm of the thoracic aorta is a rare clinical condition with significant morbidity and mortality. Patients with fast-growing aortic aneurysms show a high incidence of rupture. Gram-positive organisms, such as the Staphylococcus and Enterococcus species, are the most common cause of infection.

Case presentation

A 91-year-old man presented at our facility with high grade fever and tachypnea, which he had experienced for the previous two days. He had a history of end-stage renal disease and had been undergoing regular chest computed tomography (CT) follow-up for a left lower lung nodule. CT imaging with intravenous contrast media showed a thoracic aortic aneurysm with hemothorax. Rupture of the aneurysm was suspected. CT imaging performed a year ago showed a normal aorta. Blood samples showed a Bacillus cereus infection. The patient was successfully treated for a mycotic aortic aneurysm secondary to Bacillus cereus bacteremia.

Conclusions

Here, we report a rare of an infected aneurysm of the thoracic aorta probably caused by Bacillus cereus. Although infected aneurysms have been described well before, an aneurysm infected with Bacillus cereus is rare. Bacillus cereus, a gram-positive spore-building bacterium, can produce biofilms, which attach to catheters. It has recently emerged as a new organism that can cause serious infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bacillus cereus is a gram-positive rod-shaped bacteria found in fresh water, soil, and hospital surroundings. It is associated mainly with food poisoning, but it can cause severe infection, such as osteomyelitis, meningitis, and endocarditis, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals [1]. An infected aneurysm is a rare and life-threatening clinical condition that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Here, we report a rare case of infectious thoracic aneurysm probably caused by Bacillus cereus. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of an infected aortic aneurysm probably caused by Bacillus cereus.

Case presentation

A 91-year-old male presented with high grade fever, chills, and tachypnea. He had been experiencing these symptoms for two days prior to presentation. He had a history of end-stage renal disease and for the previous 8 months had a PermCath emplacement in the right internal jugular vein for regular hemodialysis treatment. For the past year he had also been receiving regular computed tomography (CT) follow up for a left lower lung nodule. He denied obvious chest or abdominal pain. On physical examination his blood pressure was 127/87 mmHg, pulse rate 112/min, respiration rate 20/min, and body temperature 39.6 °C. A cardiopulmonary examination showed coarse breathing sounds over the left lung and regular heart beat without jugular venous distention. Abdominal and neurological examinations showed unremarkable findings. Femoral, popliteal, and dorsalis pedis pulses were equal and palpable bilaterally.

A laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell count of 20,050/uL (reference range, 4000–10,000/uL) with 73% segmented neutrophils, hemoglobin 11.7 mg/dL (reference range, 12–14 mg/dL), creatinine 6.65 mg/dL, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) 30.45 mg/dL (reference range, < 0.3 mg/dL), blood pH 7.46, HCO3 20.9 mmol/L, base excess − 2.1 mmol/L, and pCO2 30.1 mmHg.

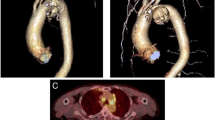

Chest X-ray showed widening of the mediastinum with left costophrenic angle blunting. Due to detection of the serious infection without a focused infection site and the chest X-ray findings, further imaging was prescribed. CT imaging with intravenous contrast media showed a thoracic aortic aneurysm (5.7 cm × 7 cm × 9 cm) at the T8 level with atelectasis of the left lung and hemothorax (Fig. 1). A CT scan for a lung nodule from a year prior to presentation showed a normal aorta (Fig. 2). The CT results combined with clinical symptoms of high fever and leukocytosis with elevated CRP, led us to suspect an infectious thoracic aneurysm. The patient was transferred to ICU. Intravenous vancomycin 1 g 3 times per week and intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g every 12 h were started empirically. The patient developed fulminant septic shock and acute respiratory failure. An emergency thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) for the thoracic aortic aneurysm was performed. After TEVAR and antibiotic administration, the patient’s septic shock improved and his clinical condition stabilized.

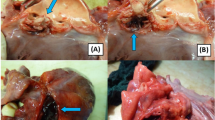

Post admission day 3 and day 5, Bacillus cereus was isolated in two sets of aerobic culture obtained from the peripheral vein. A third culture obtained from the PermCath at admission showed Bacillus cereus with a 24-h shorter positive time than those from the peripheral vein. Gray colonies with irregular perimeters were seen growing on sheep blood agar indicating beta-hemolytic bacteria (Fig. 3). Gram staining revealed gram-positive Bacillus species (Fig. 4). Bacillus cereus was isolated using the BD Phoenix 100 system. However, no bacteria grew in an anaerobic culture. Post antibiotic administration and during follow up on days 2, 3, and 4, a PermCath tip sample and three blood samples were negative for both anaerobic and aerobic cultures.

After detection of Bacillus cereus bacteremia, the patient was administered intravenous vancomycin for 6 weeks followed by fluoroquinolones oral form for 4 weeks and the PermCath was removed. Ultrasound imaging of the heart showed no pericardial effusion and no obvious vegetation. After the treatment, the patient remained asymptomatic for 6 months, without signs of relapse of infection.

Discussion and conclusions

Here, we report a rare of an infected aneurysm of the thoracic aorta probably caused by Bacillus cereus that was successfully treated by surgical and antibiotic interventions. Bacillus cereus typically presents as a gastrointestinal infection, but many cases have been reported recently that indicate it can cause life-threatening and systemic infections, such as osteomyelitis, necrotizing fasciitis, endophthalmitis, meningitis, and endocarditis, particularly in neonates, immunocompromised individuals, and intravenous drug abusers [1]. Therefore, Bacillus cereus bacteremia is a growing concern as a cause of invasive infection. However, cardiovascular complications of Bacillus cereus infection probably resulting in infected aneurysms have not r been reported previously.

The clinical isolate of Bacillus cereus is usually regarded as a contaminant, but it is still one of the pathogens causing nosocomial bloodstream infections [1]. The possible infectious routes may include bacterial contamination through the skin, venous catheter, or healthcare providers. In a retrospective study of 29 Bacillus cereus bloodstream infection cases, the main etiology was venous catheter-related (69%) [1]. In our case, an arteriovenous fistula was not made for hemodialysis due to the patient’s old age. The PermCath was used for hemodialysis for about 8 months without infection. However, at the present presentation, laboratory analysis showed that the same bacteria were present in three blood cultures (two from the peripheral vein obtained at an interval of 8 h and one from the PermCath) which meets the criteria for catheter-related bloodstream infection. The gram-positive time of the culture from the PermCath was shorter than those from the peripheral vein by about 24 h [2]. Following admission and post antibiotic administration, a culture from the tip of the PermCath and three blood cultures from post admission days 3, 4, and 5 were negative. The BD Phoenix™ system was used to identify the bacterial isolates. Antimicrobial susceptibility is determined by the antimicrobial breakpoints of Bacillus cereus in the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [1]. However, we did not conduct susceptibility tests because our laboratory could not meet the Bacillus cereus testing criteria provided in the guidelines.

Generally, the central-line-associated bloodstream infection rate in intensive care units is estimated to be 0.8 per 1000 central line days. The common pathogens causing central-line-associated bloodstream infections include Staphylococci, Enterococci, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella [3]. Bacillus species-related infections are rare in central-line-associated bloodstream infections and some reports suggest that biofilm-forming strains of the Bacillus species can cause nosocomial bacteremia by catheter infection [4]. The biofilms are an important component of bacterial survival which enables them to form communities, adhere to surfaces, and resist antibiotics [5,6,7]. In addition, the presence of indwelling medical devices increases the risk of biofilm formation [5].

An infected thoracic aortic aneurysm is a rare clinical condition and accounts for 1–3% of all aneurysms. Patients with an infected thoracic aortic aneurysm are associated with high incidences of rupture due to the fast growth of aortic aneurysms [8]. More than 60% of the pathogens causing aortic infection are gram-positive bacteria such as the Staphylococcal, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae species [9].

There are four main mechanisms that may describe the pathogenesis of infected aortic aneurysms. They include septic emboli, bacteremic seeding, direct bacterial inoculation at the time of trauma and contiguous infection. An intima with atherosclerosis allows bacteria to enter the aortic wall and is the most common pathogenesis of an infected aortic aneurysm, especially in elderly patients [9]. There were no perioperative cultures and pathologies to confirm the pathogenesis because endovascular surgery had been performed. An infected aortic aneurysm was suspected due to the clinical symptoms, laboratory examinations and radiological findings, including a mushroom-like appearance and fast-growing aorta aneurysm which grew from normal to nearly 7 cm within a year. We hypothesized that Bacillus cereus bacteremia seeding of the atherosclerotic plaque led to arterial wall infection.

In general, 4–6 weeks of vancomycin is optimal for treatment of Bacillus cereus bacteremia. In a retrospective study of 29 Bacillus cereus bloodstream infection cases, all isolates showed good susceptibility to vancomycin, MIC ≤2 (CLSI’s breakpoint for vancomycin is ≤4) [1]. However, most Bacillus cereus are resistant to penicillin and cephalosporins due to the production of β-lactamase. Other antimicrobial options, including fluoroquinolones, carbapenem, clindamycin, daptomycin and linezolid, may be effective only if the Bacillus cereus isolate is susceptible. This is because high resistance rates are still noted in some studies–approximately 10.3% for levofloxacin and 65.5% for clindamycin [1, 9, 10]. In our case, the patient was treated with vancomycin for 6 weeks followed by fluoroquinolones oral use. His clinical condition improved and a PermCath tip culture (3 days post antibiotic treatment) and three sets of blood culture in serial were negative. Generally, the antibiotic treatment can be extended for 6 to 12 weeks after surgical excision and even longer if a patient’s immunosuppressed condition is noted. Some authors suggest that life-long parenteral antibiotics may be considered if a patient has active bacteremia [9, 10].

Endovascular aortic repair may be an alternative to antibiotics for treating infected aortic aneurysms. However, the risk of recurrence of infection may be high due to embedded infection. In a systematic review of 48 cases of mycotic aortic aneurysm from 22 reports indicates that endovascular aortic repair should be considered as a method to achieve hemodynamic stability when patients present with rupture or shock [10]. In patients with comorbidities, emergency endovascular stenting may be indicated to treat ruptured infected aortic aneurysms when open repair is not possible [8, 11].

Bacillus cereus can produce biofilms, which can attach to catheters and lead to bacteremia. Bacillus cereus bacteremia is a growing concern as a cause of invasive infection especially in immunocompromised individuals.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current case report are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CLSI:

-

Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- TEVAR:

-

Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair

References

Ikeda M, Yagihara Y, Tatsuno K, Okazaki M, Okugawa S, Morita K. Clinical characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibility of Bacillus cereus blood stream infections. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2015;14:43.

Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, Craven DE, Flynn P, O’Grady NP, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45.

Atilla A, Doğanay Z, Kefeli Çelik H, Demirağ MD, S Kiliç S, Central line-associated blood stream infections: characteristics and risk factors for mortality over a 5.5-year period. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:646–652.

Kuroki R, Kawakami K, Qin L, Kaji C, Watanabe K, Kimura Y, et al. Nosocomial bacteremia caused by biofilm-forming Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis. Intern Med. 2009;48:791–6.

Aparna MS, Yadav S. Biofilms: microbes and disease. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:526–30.

Aygun FD, Aygun F, Cam H. Successful treatment of Bacillus cereus bacteremia in a patient with propionic acidemia. Case Rep Pediatr. 2016;2016:6380929.

Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–22.

Usui A. Surgical management of infected thoracic aneurysms. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2013;75:161–7.

Lopes RJ, Almeida J, Dias PJ, Pinho P, Maciel MJ. Infectious thoracic aortitis: a literature review. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:488–90.

Kan CD, Lee HL, Yang YJ. Outcome after endovascular stent graft treatment for mycotic aortic aneurysm: a systematic review. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:906–12.

Heneghan RE, Singh N, Starnes BW. Successful emergent endovascular repair of a ruptured mycotic thoracic aortic aneurysm. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:843.e1–6.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TCW drafted the manuscript. TCW, CCP, PWH and CBT revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editors of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, TC., Pai, CC., Huang, PW. et al. Infected aneurysm of the thoracic aorta probably caused by Bacillus cereus: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 19, 959 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4602-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4602-2