Abstract

Introduction

Late presentation to HIV/AIDS care which is attended by problems like, poor treatment outcomes, early development of opportunistic infections, increased healthcare costs, and mortality is a major problem in Ethiopia. Although evidences are available on the prevalence and associated factors of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care, discrepancies among findings are appreciated. Thus, the country has faced difficulties of having a single estimated data.

Objective

This study aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of late presentation of HIV positive adults to HIV/AIDS care and its predictors in Ethiopia.

Method

We searched all available articles through Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Sciences, and EMBASE databases. Additionally, we accessed articles from the Ethiopian institutional online research repositories and reference lists of included studies. We included cohort, case- control, and cross-sectional studies in our review. Besides, we utilized the weighted inverse variance random-effects model. The total percentage of variation among studies due to heterogeneity was determined by I2 statistic. Searching was limited to studies conducted in Ethiopia and published in the English language. Publication bias was checked by Egger’s regression test.

Results

A total of 8 studies with 7, 568 participants were included. The pooled prevalence of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care was 52.89% (95%CI: 35.37, 70.40). The odds of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care of frequent alcohol users [3.67(95% CI = 1.52–5.83)], high fear of stigma [3.90 (95% CI = 1.51–6.28)], chronic illness [3.34(95% CI = 1.52–5.16)], and the presence of symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis [3.06 (95% CL = 1.18–4.94)] were higher compared to participants who did not experience the preceding.

Conclusion

The prevalence of late presentation of HIV positive adults to HIV/AIDS care was high in Ethiopia. Frequent alcohol use, high fear of stigma, chronic illness, and the presence of symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis were associated with high odds of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care.

Trial registration

Registered in PROSPERO databases with the registration number of CRD42018081840.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Late presentations to Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) care is defined as persons presenting for care with a CD4 cell count below 350 cells/μl or presenting with an AIDS-defining event, regardless of the CD4 cell count [1].

HIV is a global pandemic health problem which affects all segments of the population. In 2017, around 36.9 million people were living with HIV in the world of which 21.7 million people accessed antiretroviral therapy [2]. The proportion of adults living with HIV and accessed ART (antiretroviral therapy) in the Middle East and North Africa was 29% [2].

Despite the accessibility of ART, different studies conducted in developed [3,4,5,6] and developing [7, 8] countries revealed that late presentation to HIV/AIDS care was a major problem in different countries. It was reported that in Sub-saharan Africa, over one-third of the HIV infected individuals presented to HIV/AIDS care late [9].

Accordingly, adults who presented lately to HIV/AIDS care encountered many problems, like poor treatment outcomes, increased mortality [3], high healthcare costs [10], and development of opportunistic infections [3]. Even though different strategies, like frequent change of ART treatment guidelines, extensive education about the management of HIV/AIDS, free testing, and treatment were delivered, late presentation is still a problem in Ethiopia.

Many efforts were made to determine the prevalence and associated factors of late presentation of HIV positive adults to HIV/AIDS care in Ethiopia. However, discrepancies among studies have made the acquisition of a single representative data difficult in Ethiopia. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of late presentation of HIV positive adults to HIV/AIDS care and its predictors.

Method

Protocol registration

The protocol of this systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with a registration number of CRD42018081840.

Reporting

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline was used to report the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis [11] (Additional file 1).

Databases and searching strategies

Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Sciences, and EMBASE were used for searching all available articles. Additionally, we searched articles using the reference lists of included studies. We also accessed the Ethiopian institutional online research repositories using the following searching terms: “late presentation”, “delayed presentation”, “advanced stage presentation”, “late-stage presentation”, “Human Immune Deficiency Virus care”, “Human Immune Deficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome care”, “HIV care”, “HIV/AIDS care”, “associated factors”, “predictors”, “determinants”, “risk factors”, “HIV positive individuals”, “HIV”, “adults”, and “Ethiopia”. The searching string was developed using “OR” and/or “AND” Boolean operators. Search details for PubMed databases were illustrated (Additional file 2). We conducted the search until 24 July, 2018.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles included met the following criteria: [1] observational studies, including cohort, case-control and cross-sectional, [2] published and unpublished studies at any time, [3] being conducted in Ethiopia in the English language, and [4] studies that reported prevalence/or predictors of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. However, conference papers, editorials, trials, reviews, program evaluations, and qualitative studies were excluded.

Outcome measurement

Out of the included studies, three [12,13,14] were defined late presentation as people living with HIV/AIDS and had CD4 count 350cells/mm3 or World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage III or IV during their first clinical visit for HIV care, four [15,16,17,18] were defined late presentation as people with WHO stage 3 or 4 irrespective of CD4 lymphocyte count or a CD4 lymphocyte count of less than 200/μl irrespective of clinical staging at the first visit for HIV/AIDS care, and one [19] was defined late presentation as HIV/AIDS patients registered with CD4 cell counts of < 100/ml.

In this study, chronic illness was defined as disease that needs three or more months of treatment with specified lists of diseases [20].

Study selection and quality assessment

Primarily, all retrieved studies were imported to Endnote version 7 citation manager. Consequently, duplicated studies were carefully removed from Endnote. Then, two independent authors screened and assessed the titles and abstracts and reviewed the full texts. Any disagreement was solved through discussion and communication with the primary authors of the studies. After the full-text review, two investigators assessed the quality of the studies using the Joanna Brigg’s Institute (JBI) quality appraisal criteria adapted for cohort and case-control studies independently [11].

We used the following items to critically appraise studies. For cohort studies, we employed, [1] similarity of groups, [2] similarity of exposure measurement, [3] validity and reliability of measurement, [4] identification of confounders, [5] strategies to deal with confounders, [6] appropriateness of groups/participants at the start of the study, [7] validity and reliability of outcomes measured, [8] sufficiency of follow up time, [9] completeness of follow-up or descriptions of reasons for loss to follow-up, [10] strategies to address incomplete follow-ups, and [11] appropriateness of statistical analysis. For case-control studies we utilized, [1] comparable groups, [2] appropriateness of cases and controls, [3] criteria to identify cases and controls, [4] standard measurement of exposure, [5] similarity in measurement of exposure for cases and controls, [6] handling of confounders, [7] strategies to handle confounders, [8] standard assessment of outcome, [9] appropriateness of duration for exposure, and [10] appropriateness of statistical analysis. Studies were considered as low risk whenever fitted to 50% and/or above quality assessment checklist criteria were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Two independent authors extracted the data. Any disagreements between the authors were solved by discussion and consensus. Consequently, the first author of the study, year of publication, study area, design, population, sample size, prevalence of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care and/or identified associated factors were extracted. For associated variables reported in the primary studies, the AOR was extracted because of its importance for having adjusted and/or controlled possible confounders.

Data analysis

To estimate the pooled prevalence of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care and pooled AOR of identified variables, we used the weighted inverse variance random-effects model. We assessed the percentages of total variations across studies using I2 statistics. The values of I2, 25, 50, and 75% represented low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Publication bias across studies was checked using Egger’s regression test. A Stata version 11 (Stata Corp, college station, TX, USA) statistical software was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Searching results

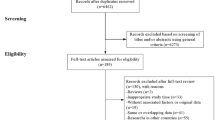

On the whole, 1206 citations were searched using different electronic databases of which 1133 articles were found from PubMed, 60 from Google scholar, 5 from EMBASE, 2 from the web of science, 5 from reference lists of included studies, and 1 from the Ethiopian research repositories. At the beginning, 71 articles were removed due to duplicates and 1115 due to irrelevant titles and abstracts. After a full-text review of 20 articles, 7 were removed due to study areas and 5 due to study designs. Finally, 8 articles were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

A total of eight studies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] with 7568 participants were included in this study. Out of these studies, four [12, 15, 16, 19] were conducted through the case-control study design and the other four [13, 14, 17, 18] were retrospective cohort. Regarding study areas, three studies [15, 17, 18] were conducted in Oromia, two [13, 14] in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR), one [16] in Amhara, one [12] in Tigray, and one [19] in Harari. Detailed characteristics of included studies were described in Table 1.

Quality of included studies

Out of 8 studies, four [13, 14, 17, 18] were assessed using the JBI checklist for cohort studies and four [12, 15, 16, 19] were assessed using the JBI checklist for case-control studies. None of the studies were excluded after quality assessment.

Meta- analysis

Publication bias was not observed among the included studies according to an Egger’s regression test assessment (p-value = 0.367).

Qualitative description

Out of 8 studies, four were considered to determine the pooled prevalence of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. However, all included studies were considered to determine the predictors of late presentation.

Prevalence of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care

The prevalence of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care ranged from 34.4% in SNNPR [14] to 67.7% in Oromia [17]. To estimate the pooled prevalence, four studies [13, 14, 17, 18] were used. Consequently, the pooled prevalence of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in Ethiopia was 52.89% (95% CI: 35.37, 70.40; I2 = 99%; P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Predictors of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, predictors were categorized into three thematic areas like, socio-demographic, clinical and treatment-related predictors.

Socio-demographic related factors

Two studies [14, 17] reported that female sex was significantly associated to late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. On the contrary, one study reported that male respondents were 7.19 times more likely to present late to HIV/AIDS care than females 7.19 (95% CI: 1.279–8.447) [19]. However, in this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled AOR of late presentation was not significantly associated the female sex (Fig. 3).

Two studies [15, 16] showed that frequent alcohol use was a factor associated late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. The pooled AOR of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care among frequent alcohol users versus no alcohol users was 3.67(95% CI: 1.52, 5.83) (Fig. 3). Additionally, two studies [12, 15] reported that two or more sexual partners were associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. However, the pooled result revealed that it is not significantly associated with the outcome variable (Fig. 3).

Clinical-related factors

Two studies [12, 16] reported that there was an association between the fear of stigma and late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. The pooled AOR of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care among adults with high fear of stigma was 3.90 (95% CI: 1.51, 6.28) compared to adults with low fear (Fig. 3).

Two studies [15, 16] noted that the presence of symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis was significantly associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. The pooled AOR of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care among those who had symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis versus those who had no symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis was 3.06 (95% CI:1.18,4.94) (Fig. 3).

Treatment-related factors

Two studies [12, 15] observed that HIV positive individuals who had chronic illness were significantly associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. The pooled AOR of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care among those with chronic illness versus those who had no chronic illness was 3.34(95% CI: 1.52, 5.16) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

In this work, the pooled prevalence of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in Ethiopia was 52.89% (95% CI: 35.37, 70.40). High fear of stigma, frequent alcohol use, symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis, and the presence of chronic illnesses were significantly associated with the problem.

This result is in line with those of studies conducted in Canada (46%) [4], Brazil (69.8%) [21], France (47.7%) [22], and Central Haiti (65%) [23] but lower than those of studies conducted in Cameron (89.7%) [24], South Africa (79%) [25], Benin (84.4%) [26], Asia (72%) [27],and Georgia (71.1%) [28]. This might be due to the availability of nation-wide health extension programs that help to create awareness about early diagnosis, enrolment, and treatment through community conversations, scaling up benchmark activities, and regular home visits.

On the other hand, the finding of this study was higher than that of a study conducted in West Africa (23%) [29]. The possible explanation for the variation might be the huge number of rural population with low education which leads to resistance to new health information.

Regarding predictors, fear of stigma was significantly associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. The odds of HIV positive adults with high fear of stigma were nearly four times more likely to present late to HIV/AIDS care compared to their counterparts. This finding was in line with that of a systematic review and meta-analysis done in low and middle-income countries [30] and Zimbabwe [31]. This could be due to the fact that AIDS stigma affects social interaction and preventive behaviors, like healthcare seeking and HIV testing. Moreover, stigma results in social isolation that prevents people from getting HIV/AIDS related information.

This study revealed that late presentation to HIV/AIDS care among frequent alcohol user adults were nearly 4 times more likely compared to non-frequent alcohol users. This finding is supported by studies conducted in India [32] and France [33]. This was due to the fact that alcohol use decreases awareness and inhibits judgments. In addition, alcohol consumption leads to significant impairment of information processing and motor performance and induces a specific set of physical sensations [34]. Moreover, frequent alcohol consumption results in attention deficient, impulsive behavior, aggressiveness, and intoxication. As a result, patients may have less concern about their own health.

Furthermore, this study showed a significant association between late presentation to HIV/AIDS care and symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis. Late presentation of those who had symptoms during HIV diagnosis was nearly three times more likely compared to those who had no symptoms. This finding is consistent with those of studies done in central Haiti, Cameroon [23, 24] and Switzerland [35]. This could be explained by the fact that the presence of symptoms at the time of diagnosis could result in identity confusion and hopelessness in a person’s life which in turn affects early healthcare seeking behavior.

Finally, HIV positive adults with chronic illnesses during the time of HIV infection were identified as predictors of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. According to this study, late presentation of adults with chronic illnesses was nearly 3.5 times more compared to adults who had no such illnesses. This finding was in agreement with that of a study done in Cameroon [24, 31]. The reason may be that adults who had chronic illnesses preferred treatment for the other illnesses primarily. As a result, they presented late to HIV/AIDS care. Moreover, individuals might attend HIV testing and treatment whenever they develop HIV/AIDS-related diseases.

Conclusion

Late presentation to HIV/AIDS care of adults living with HIV/AIDS was found to be high. High fear of stigma, frequent alcohol use, symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis, and chronic illnesses were significantly associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care. Therefore, we recommend community-based outreach early HIV testing and counseling for all individuals. Early enrollment and linkage to HIV/AIDS care also needs to be strengthened. Furthermore, awareness creation about the problems of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care is important.

Strength and limitation of the study

I-square shows a significant heterogeneity. Hence, we applied random-effect model and deal with the reasons of heterogeneity. Therefore, the pooled result can be used for policy implication because we checked that the outcome is similar in all studies with binary outcome (being late or not lately initiate ART), similar study participants involved, similar study design use, and all studies are in good methodological quality.

To be sure, this high quality attempt is not free from limitations as it may be subject to the unpublished and unaddressed issues. The result of this work is not representative of all regions since data were not gathered from Afar, Dire Dawa, Addis Ababa, Somali, Gambella and Beshangul Gumuze.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during study included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immunodeficiency Virus

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral Therapy

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

References

Antinori A, Coenen T, Costagiola D, Dedes N, Ellefson M, Gatell J, et al. Late presentation of HIV infection: a consensus definition. HIV medicine. 2011;12(1):61–4.

UNAIDS. GLOBAL HIV STATISTICS F A C T S H E E T. 2017.

Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, AdA M, Brockmeyer N, Casabona J, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: results from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE). PLoS medicine. 2013;10(9):e1001510.

Althoff KN, Gange SJ, Klein MB, Brooks JT, Hogg RS, Bosch RJ, et al. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(11):1512–20.

Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Kaslow RA, Bey AK, Vermund SH. Factors associated with delayed initiation of HIV medical care among infected persons attending a southern HIV/AIDS clinic. South Med J. 2006;99(5):472.

Lanoy E, Mary-Krause M, Tattevin P, Perbost I, Poizot-Martin I, Dupont C, et al. Frequency, determinants and consequences of delayed access to care for HIV infection in France. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(1):89.

Battegay M, Fluckiger U, Hirschel B, Furrer H. Late presentation of HIV-infected individuals. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(6):841–51.

Kigozi IM, Dobkin LM, Martin JN, Geng EH, Muyindike W, Emenyonu NI, et al. Late disease stage at presentation to an HIV clinic in the era of free antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2009;52(2):280.

Kigozi IM, Dobkin LM, Martin JN, Geng EH, Muyindike W, Emenyonu NI, Bangsberg DR, Hahn JA. Late disease stage at presentation to an HIV clinic in the era of free antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. PMC. 2009;2(52):280.

Krentz H, Auld M, Gill M. The high cost of medical care for patients who present late (CD4< 200 cells/μL) with HIV infection. HIV medicine. 2004;5(2):93–8.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Gelaw YA, Senbete GH, Adane AA, Alene KA. Determinants of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in southern Tigray zone, northern Ethiopia: an institution based case–control study. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12(1):40.

Gebru T, Lentiro K, Jemal A. Perceived behavioural predictors of late initiation to HIV/AIDS care in Gurage zone public health facilities: a cohort study using health belief model. BMC research notes. 2018;11(1):336.

Gesesew H, Abdo Z, Assefa H. Late presentation to HIV care and its associated factors in Shashamanne hospital. Southeastern Ethiopia: A Retrospective Study; 2014. p. 232–8.

Gesesew HA, Tesfamichael FA, Adamu BT. Factors affecting late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in Southwest Ethiopia: a case control study. Public Health Research. 2013;3(4):98–107.

Abaynew Y, Deribew A, Deribe K. Factors associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in south Wollo ZoneEthiopia: a case-control study. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8(1):8.

Gesesew HA, Ward P, Woldemichael K, Mwanri L. Late presentation for HIV care in Southwest Ethiopia in 2003–2015: prevalence, trend, outcomes and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):59.

Gesesew H, Tsehaineh B, Massa D, Tesfay A, Kahsay H, Mwanri L. The prevalence and associated factors for delayed presentation for HIV care among tuberculosis/HIV co-infected patients in Southwest Ethiopia: a retrospective observational cohort. Infectious diseases of poverty. 2016;5(1):96.

Asrat A. Delayed Presentation for ART Care among PeopleLiving with HIV in Public Hospitals, Harari Region. Harar Bulletin of Health Sciences. 2010;1(3).

Souri S, Symonds NE, Rouhi A, Lethebe BC, Garies S, Ronksley PE, et al. Identification of validated case definitions for chronic disease using electronic medical records: a systematic review protocol. Systematic reviews. 2017;6(1):38.

MacCarthy S, Brignol S, Reddy M, Nunn A, Dourado I. Late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in Brazil among men who self-identify as heterosexual. Revista de saude publica. 2016;50:54.

KdA W, Dray-Spira R, Aubrière C, Hamelin C, Spire B, Lert F, et al. Frequency and correlates of late presentation for HIV infection in France: older adults are a risk group–results from the ANRS-VESPA2 Study, France. AIDS care. 2014;26(sup1):S83–93.

Louis C, Ivers L, Smith Fawzi M, Freedberg K, Castro A. Late presentation for HIV care in Central Haiti: factors limiting access to care. AIDS Care. 2007;19(4):487–91.

Luma HN, Jua P, Donfack O-T, Kamdem F, Ngouadjeu E, Mbatchou HB, et al. Late presentation to HIV/AIDS care at the Douala general hospital, Cameroon: its associated factors, and consequences. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):298.

Fomundam H, Tesfay A, Mushipe S, Mosina M, Boshielo C, Nyambi H, et al. Prevalence and predictors of late presentation for HIV care in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2017;107(12):1058–64.

Zannou DM, Gandaho PB, Azon-Kouanou A, Ahouada C, Agbodande KA, Wanvoegbe A, et al. Late presentation to care among people living with HIV in Cotonou, Benin: a retrospective analysis from 2003 to 2014. Open Journal of Internal Medicine. 2017;7(04):123.

Jeong SJ, Italiano C, Chaiwarith R, Ng OT, Vanar S, Jiamsakul A, et al. Late presentation into care of HIV disease and its associated factors in Asia: results of TAHOD. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2016;32(3):255–61.

Chkhartishvili N, Chokoshvili O, Bolokadze N, Tsintsadze M, Sharvadze L, Gabunia P, et al. Late presentation of HIV infection in the country of Georgia: 2012-2015. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186835.

Hønge BL, Jespersen S, Aunsborg J, Mendes DV, Medina C, da Silva TD, et al. High prevalence and excess mortality of late presenters among HIV-1, HIV-2 and HIV-1/2 dually infected patients in Guinea-Bissau-a cohort study from West Africa. The Pan African medical journal. 2016;25.

Gesesew HA, Gebremedhin AT, Demissie TD, Kerie MW, Sudhakar M, Mwanri L. Significant association between perceived HIV related stigma and late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173928.

Nyika H, Mugurungi O, Shambira G, Gombe NT, Bangure D, Mungati M, et al. Factors associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in Harare City, Zimbabwe, 2015. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):369.

Yadav U, Chandrasekharan V, Guddattu V, Gruiskens J. Mixed method approach for determining factors associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in southern India. J Postgrad Med. 2016;62(3):173.

Elenga N, Geroger-Sow M-T, Nacher M. Risk factors for late presentation for care among HIV-infected patients in Guadeloupe: 1988-2009. J AIDS Clinic Res. 2012;3(7):1000166.

Hull JG, Bond CF. Social and behavioral consequences of alcohol consumption and expectancy: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1986;99(3):347.

Hachfeld A, Ledergerber B, Darling K, Weber R, Calmy A, Battegay M, et al. Reasons for late presentation to HIV care in Switzerland. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):20317.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the authors of primary study included in this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grants from funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GM conceived and designed this this systematic review and meta-analysis. GM, AD and AE established the search strategy, extract the data, assess the quality of included study, analysis and finally wrote the review. All authors had prepared the manuscript. Finally, the authors read, modify and agree on the final prepared manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA guideline checklist. (DOCX 300 kb)

Additional file 2:

Searching strings used for PubMed. (DOCX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Belay, G.M., Endalamaw, A. & Ayele, A.D. Late presentation of HIV positive adults and its predictors to HIV/AIDS care in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 19, 534 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4156-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4156-3