Abstract

Background

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is frequently diagnosed in the Emergency Department (ED). Staphylococcus aureus (SA) is an uncommon isolate in urine cultures (0.5–6% of positive urine cultures), except in patients with risk factors for urinary tract colonization. In the absence of risk factors, community-acquired SA bacteriuria may be related to deep-seated SA infection including infective endocarditis. We hypothesized that SA bacteriuria could be a warning microbiological marker of unsuspected infective endocarditis in the ED.

Methods

This is a retrospective chart review of consecutive adult patients between December 2005 and February 2018. All patients admitted in the ED with both SA bacteriuria (104 CFU/ml SA isolated from a single urine sample) and SA bacteremia, without risk factors for UT colonization (i.e., < 1 month UT surgery, UT catheterization) were analyzed. Diagnosis of infective endocarditis was based on the Duke criteria.

Results

During the study period, 27 patients (18 men; median age: 61 [IQR: 52–73] years) were diagnosed with community-acquired SA bacteriuria and had subsequently documented bacteremia and SA infective endocarditis. Only 5 patients (18%) had symptoms related to UT infection. Median delay between ED admission and SA bacteriuria identification was significantly shorter than that between ED admission and the diagnosis of infective endocarditis (1.4 ± 0.8 vs. 4.3 ± 4.2 days: p = 0.01). Mitral and aortic valves were most frequently involved by infective endocarditis (93%). Mortality on day 60 reached 56%.

Conclusions

This study suggests that community-acquired SA bacteriuria should warn the emergency physician about a potentially associated left-sided infective endocarditis in ED patients without risk factors for UT colonization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Staphylococcus aureus (SA) is an unusual cause of urinary tract infection (UTI) which prevalence ranges between 0.15 and 4.3% [1]. SA bacteriuria has been described predominantly in patients with predisposing conditions for ascending SA colonization (e.g., history of urinary obstruction, urinary catheter, recent urological surgical procedures, malignancy and recent hospitalization) [1,2,3]. Nevertheless, it is commonly interpreted as a genitourinary infection [2,3,4]. In up to 34% of cases, SA bacteriuria is associated with SA bacteremia [1, 2, 5, 6]. These patients have frequently a complicated course with higher hospital mortality [3, 5,6,7].

In the absence of risk factors for SA colonization, SA bacteriuria may be related to deep-seated SA infection, and specifically to infective kidney embolisms associated with an underlying infective endocarditis [3, 6]. Accordingly, this observational study aimed at describing the clinical presentation of patients admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) with SA bacteriuria who were subsequently diagnosed with SA infective endocarditis.

Methods

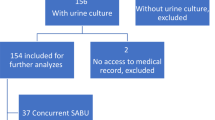

This case series is based on a retrospective chart review of consecutive adult patients admitted initially to the ED of our institution between December 2005 and February 2018, with SA bacteriuria identified in the ED but no risk factors for urinary tract colonization, and who were subsequently diagnosed with definitive infective endocarditis. Patients were studied when (i) admitted to the ED, with (ii) initial SA bacteriuria on the first urine sample, (iii) subsequent identification of SA bacteremia, and (iv) definite diagnosis of infective endocarditis confirmed at hospital discharge. According to the French law, approval from an ethics committee, as well as consent to participate were not required since this study was retrospective and performed on existing data without direct intervention on human subjects.

Bacteriuria was defined as a positive culture > 104 CFU/ml SA isolated from a single urine sample. Risk factors for urinary tract colonization included a history of urinary obstruction, urinary catheter, recent urological surgical procedures, malignancy and recent hospitalization. Concomitant bacteremia was defined as at least one blood culture positive for SA within 72 h following urine culture [2]. Diagnosis of definite infective endocarditis was based on the presence of typical echocardiographic findings (in conjunction of SA bacteremia) and modified Duke’s criteria were secondarily used to precisely determine major and minor criteria [8]. All patients underwent a transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography. Demographic data, presence of a urinary catheter or inserted device, main reason for ED admission, UTI symptoms [9], diagnosis at ED discharge, source of bacteremia, SA antibiotic susceptibility, time lag between ED admission and diagnosis of infective endocarditis, characteristics of infective endocarditis, and 2-month mortality were collected (from shared medical file).

Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the difference in delay between bacteriuria and diagnosis of infective endocarditis by echocardiography.

Results

During the study period, 27 patients (18 men; median age: 61 [IQR: 52–73] years) were diagnosed in the ED with a community acquired SA bacteriuria and had subsequently documented bacteremia and SA definitive infective endocarditis. Median Charlson index was 2.0 [IQR: 1–4.5] and comorbidities included valve disease (30%), prosthetic valve surgery (18%), diabetes (18%), implantable catheter (18%), cirrhosis (11%) and cancer (7%). A single patient was an intravenous drug user (Table 1). Patients presented to the ED after a mean of 4 ± 3 days after the onset of symptoms, mostly with fever (59%) and confusion (48%). Only 5 patients (18%) had symptoms related to UTI (dysuria: n = 1; hematuria: n = 2; lumbar pain: n = 2). Five patients (18%) had a cardiac murmur, three having also a prosthetic valve. All patients were hospitalized. At ED discharge, 21 patients (78%) had a diagnosis of acute infection which site was identified in 14 patients, but only 5 of them were diagnosed out of hand with infective endocarditis (Table 1). SA strains were methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) in 25 patients (93%). The source of SA infection was documented in 59% of patients and was mainly of cutaneous or joint origin (Table 1).

Mean delay between ED admission and SA bacteriuria identification was significantly shorter than that separating ED admission and the diagnosis of infective endocarditis (1.4 ± 3.1 vs. 4.3 ± 4.2 days: p = 0.0016). Moreover, SA bacteriuria from urine sample obtained in the ED was detected earlier than SA bacteremia with a mean difference of 1.9 days.

Mitral and aortic valves were most frequently involved by infective endocarditis (93%) (Table 1). Heart surgery was required in seven patients (4 men; median age: 65 years [IQR: 48–70]) after a median of 10 days (IQR: 7.5–23.5) from ED admission. Indications for surgery included uncontrolled infection despite adapted antibiotherapy (n = 3), massive valvular insufficiency (n = 5), or intractable pulmonary edema (n = 3). Mortality on day 60 reached 56%.

Discussion

The clinical presentation of infective endocarditis is commonly non-specific and constitutes a syndromic diagnosis which should be suspected on the presence of compatible clinical signs associated with predisposing factors (e.g., valvulopathy, prosthetic valve, intravenous drug use), rather than on a single definitive test result [8]. In the present study, infective endocarditis was suspected mainly because of persistent bacteremia, but was also identified in the subset of shocked patients during initial bedside echocardiographic hemodynamic assessment. Median time from ED admission to diagnosis of infective endocarditis reached 3 [IQR 1–6.5] days, and was much shorter than that previously reported in the general population [10]. SA bacteriuria was identified even earlier (1.4 ± 0.8 days) after ED admission in all patients, and mostly in the absence of UTI symptoms [1, 4, 6]. This is presumably explained by the liberal use of urine culture in the ED [11]. Indeed, reasons for ED admission were not related to an infectious origin in more than half of the cases (59%) and diagnosis at ED discharge was non-infectious in 22% of patients. These results are in keeping with previous studies which reported initial misdiagnoses in 26 to 33% of patients with definite infective endocarditis [5].

Even in the absence of UTI, SA bacteremia is frequently (8 to 34%) accompanied by bacteriuria [1, 2, 4,5,6], and patients with both infectious events have an increased risk for complicated SA bacteremia [1, 7], and a two-fold increased risk for admission in intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital mortality [1, 6, 12]. In the present series, the mortality at 2 months after admission to ED was as high as 56%. This suggests that community-acquired SA bacteriuria detected in ED behaves as an early warning signal of potential poor outcome in patients with underlying infective endocarditis. In the present study, SA bacteriuria was related to complicated bacteremia secondary to bone/joint infections in 37% of patients, a similar proportion to that previously reported [4, 7]. Importantly, SA bacteriuria was identified significantly earlier than infective endocarditis in all our patients, with a mean difference of 2.9 days. This time difference could allow initiating antibiotic therapy earlier and may reduce complications of SA bacteremia since a delay of 48 h in antibiotics initiation is a risk factor for metastatic infection [5]. Considering the increased rates of ICU admission and mortality and the non-specific clinical presentation of infective endocarditis [8], SA bacteriuria could be helpful to accelerate both its identification and treatment, when used as a potential indicator of associated SA bacteremia with renal micro-abscesses [1, 6, 13]. In keeping with this hypothesis, 19 out of 27 patients (70%) exhibited vascular phenomena which are consistent with multiple septic systemic emboli, including the development of renal micro-abscesses with associated SA bacteriuria. Accordingly, MSSA, which is most frequently isolated in patients with metastatic SA bacteremia [2, 4], was predominantly identified and infective endocarditis involved left-sided valves in most of the herein reported cases.

The present study lacks power to ascertain the association between SA bacteriuria, SA bacteremia and infective endocarditis. In addition, its retrospective design precluded evaluating patients with isolated SA bacteriuria but no bacteremia to determine the specificity of this potential microbiological “marker”. Similarly, the sensitivity of SA bacteriuria could not be assessed since all patients with SA bacteremia failed to undergo urine culture at the time of blood culture sampling. Accordingly, these preliminary data need to be prospectively confirmed in a larger multicenter cohort of ED patients. However, data were collected and analyzed exhaustively by an independent adjudication committee.

Conclusion

In closing, this study suggests that community-acquired SA bacteriuria should not be interpreted as an isolated UTI or colonization of urinary tract in the absence of risk factors, but should rather warn the front-line physician about a potential associated SA bacteremia secondary to a left-sided infective endocarditis. Whether this simple and easily accessible microbiological “marker” allows reducing the delay of both diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis in patients presenting to the ED with undifferentiated symptoms remains to be confirmed by prospective large-scale studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since they contain confidential personal information that could help identify the patients but can be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and after removal of all personal information.

Abbreviations

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

- SA :

-

Staphylococcus aureus

- UTI :

-

Urinary tract infection

References

Al Mohajer M, Darouiche RO. Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria: source, clinical relevance, and management. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012;14:601–6.

Choi SH, Lee SO, Choi JP, Lim SK, Chung JW, Choi SH, et al. The clinical significance of concurrent Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria in patients with S. aureus bacteremia. J Inf Secur. 2009;59:37–41.

Asgeirsson H, Kristjansson M, Kristinsson KG, Gudlaugsson O. Clinical significance of Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria in a nationwide study of adults with S. aureus bacteraemia. J Inf Secur. 2012;64:41–6.

Pulcini C, Matta M, Mondain V, Gaudart A, Girard-Pipau F, Mainardi JL, et al. Concomitant Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria is associated with complicated S. aureus bacteremia. J Inf Secur. 2009;59:240–6.

Horino T, Sato F, Hosaka Y, Hoshina T, Tamura K, Nakaharai K, et al. Predictive factors for metastatic infection in patients with bacteremia caused by methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:24–8.

Huggan PJ, Murdoch DR, Gallagher K, Chambers ST. Concomitant Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria is associated with poor clinical outcome in adults with S. aureus bacteraemia. J Hosp Infect. 2008;69:345–9.

Perez-Jorge EV, Burdette SD, Markert RJ, Beam WB. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) with associated S. aureus bacteriuria (SABU) as a predictor of complications and mortality. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:208–11.

Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG Jr, Ryan T, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:633–8.

Grigoryan L, Trautner BW, Gupta K. Diagnosis and Management of Urinary Tract Infections in the outpatient setting: a review. JAMA. 2014;312:1677.

Damasco PV, Ramos JN, Correal JCD, Potsch MV, Vieira VV, Camello TC, et al. Infective endocarditis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: a 5-year experience at two teaching hospitals. Infection. 2014;42:835–42.

Pallin DJ, Ronan C, Montazeri K, Wai K, Gold A, Parmar S, et al. Urinalysis in acute care of adults: pitfalls in testing and interpreting results. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1:ofu019.

Chihara S, Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Hota B. Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria as a prognosticator for outcome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:225.

Karakonstantis S, Kalemaki D. The clinical significance of concomitant bacteriuria in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. A review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis. 2018;50:648–59.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TL, BF and PV designed and conducted the study, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; ACHP analyzed the data and critically reviewed the manuscript; AB, LL, MG, TD included patients, collected the data and critically reviewed the manuscript; OB analyzed the microbiological data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval from an ethics committee, as well as consent to participate were not required since this study was retrospective. However, we obtained the permission from the IT department in charge of the patients’ files to access the raw data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lafon, T., Hernandez Padilla, A.C., Baisse, A. et al. Community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria: a warning microbiological marker for infective endocarditis?. BMC Infect Dis 19, 504 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4106-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4106-0