Abstract

Background

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection is estimated to be the most common sexually transmitted infection. The present systematic review summarizes data regarding the prevalence of HPV and the distribution of subtypes in heterosexual male partners of women, who were diagnosed with any grade of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Methods

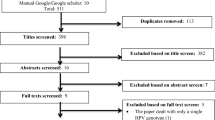

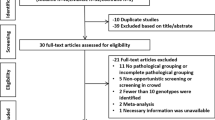

We conducted a systematic review of the literature by Medline and Google Scholar databases using the terms “Human Papillomavirus” or “HPV” plus “men” or “male partners” or “women with CIN”. We included original published English-language articles published from 1/1/2000 until 1/1/2018 that had screened male partners of women with CIN using HPV DNA testing. We excluded studies that they overlapped with other included studies or were unrelated to the study subject.

Results

We included a total of 12 publications, which reported the prevalence of HPV in free-clinical signs male partners of women with CIN. The largest proportion of the studies were from South America (seven studies), and the rest from Europe. The mean age of participants was 35.18 + − 3.47 years. HPV prevalence ranged from 12.9 to 86%; the total HPV prevalence among the studies was 49.1%, while ten out twelve studies (83.3%) demonstrated prevalence > 20%. Between the studies, the distribution of HPV subtypes varied on the basis of the method used, on the population and on the geographic region. A great variety of subtypes were detected, including 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 66, 68, 81 and 83. In six studies the HPV 16 was the most frequent, while in two others the HPV 6 and HPV 83.

Conclusions

Until now, there are not precise screening or surveillance guidelines for the management of partners of women with CIN. This population is frequently colonized by various HPV subtypes and therefore need to be screened in an effort to reduce the infection in both sexes. The screening test could include detection/identification of HPV subtypes by a molecular assay, followed by peniscopy only in the positive cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human Papillomavirus infection (HPV) is estimated to be among the most common sexual transmitted infections. Most HPV infections are asymptomatic or subclinical and become undetectable over time. It is well known that some HPV subtypes can cause anogenital warts, dysplastic and/or neoplastic lesions in women and men (heterosexual and men who have sex with men), generating a considerable economic distress within societies [1,2,3].

There are more than 150 HPV subtypes, which have been grouped according to their oncogenic capacity into High-Risk (HR) and Low-Risk (LR) [4]. Epidemiological studies show that HR are associated in women with invasive cervical cancer and its precursor lesion, the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), whereas in men HR subtypes can cause head and neck squamous carcinoma and penile cancer [5, 6].

CIN is a potentially premalignant transformation and dysplasia of squamous cells of the cervix, caused mainly by the HR-HPV types 16 and 18 [7]. Usually, CIN is eliminated by the host’s immune system without any intervention, but, in some cases, when it left untreated, CIN can progress to cervical cancer [8]. Even though there is a vast bibliography regarding the management of the women diagnosed with CIN, there is very limited number of studies focused on the measures that must be applied in male sexual partners of women with CIN. A positive result for HPV infection usually stress women, who are worried about disclosing the result to others and the fact that there is not a clear management of their sexual partners make the disclosing even more difficult [9]. Previous studies have demonstrated that partners of women with CIN can be infected by the virus, while, the risk of developing cancer seems to be higher in men’s second wives when their first wives died from cervical cancer [10].

The present study summarizes data regarding the global prevalence of HPV and the distribution of subtypes in heterosexual male partners of women, who were diagnosed with any grade of CIN. The scope of this review primarily focuses on the characteristics and the results of the selected studies. Assessing the prevalence of HPV infection of male partners is the first step in order to understand the natural history of HPV in couples with women with CIN, and to finally clarify the management of the male partners.

Methods

In this systematic review we conducted a systematic search in two online databases, Medline and Google Scholar, searching for studies published from 1/1/2000 until 1/1/2018. For our research we use the terms “HPV” OR “Human Papillomavirus”, plus “men”, “male partners” and “women with CIN”. References cited in retrieved articles were also assessed. Eligible studies had to: 1) screen a population of heterosexual male partners of women with CIN, 2) include HPV DNA testing, and 3) be written in English language; all of which were including criteria. The evaluation of articles was performed based on their relevance of the title, abstract and manuscript review. In order to minimize the risk of bias, the evaluation of the articles was performed by two reviewers, independently. We performed a qualitative synthesis of the data for the prevalence and subtype distribution, since the articles varied significantly based on the study design, on the participants characteristics and on the molecular assays used. The prevalence of HPV in the selected studies was calculated by dividing the number of HPV-positive male partners by the total number of male partners of women with CIN. Unfortunately, there were no data for male partners of women without CIN in order to conclude if male partners of women with CIN have higher risk for HPV infection. Hence, no further statistical analysis was possible to be done. All the computations were calculated by R program (RStudio Team (2015). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/).

Results

From the 7682 abstracts reviewed, 35 articles were selected and among them, 12 met the inclusion criteria (Table 1) [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Reasons for the exclusion of 23 articles were that they overlapped with other included studies, they were written in non-English language or they were unrelated to the study subject (see Table 2).

Τhe articles were classified based on the time period when the samples were collected rather than the year of publication (Table 1). Five studies originated from Brazil, two from Spain, one from Netherlands, one from Italy, one from Mexico, one from Colombia and one from Czech Republic. There were differences regarding the time of the samples’ collection: in eight before 2010, in three after 2010. Only one study did not mention the period of the collection of specimens. This study was published in 2012, took the ethical approval in 2009 and the collection of samples would have been rationally done after 2009 and before 2012; so, it was placed between Afonso (collection 2000–2010) and Rob (2013–2015).

In these studies, a variety of molecular assays were used for the detection of HPV in samples, obtained from men, who were sexual partners of women with CIN (Table 3). Information regarding the characterization of HPV subtypes (both HR and LR) were given in nine studies; the remaining three studies assessed HPV detection without subtyping (Table 3). In these three studies the methods used (PCR with universal primers followed by restriction or hybridization) had only the capacity to detect the virus and not to identify subtypes.

Regarding the collection of specimens, the majority of the studies describe similar anatomical sites (the penile groove area, the glans penis, penile body and procure) for sampling by brushing (Table 3). Only one study used self-obtained samples as previously described by Weaver et al. [23]. Apart from the HPV DNA test, half of the studies used peniscopy as an additional diagnostic tool.

Table 4 describes the characteristics of the couples. Four articles included only monogamous couples, while the remaining eight articles either did not mention whether couples were monogamous or if they included both monogamous and non-monogamous couples. In addition, differences in the time of relationship were also observed; four studies included couples with minimum duration of 6 months, two studies at least 1 year, one study at least 2 years and five studies did not mention the duration of the relationship.

Regarding the circumcised participants, four studies included circumcised male partners, one study excluded them; the rest of the studies did not mention if their male partners were or were not circumcised. On the other hand, differences in the use of condoms have also been observed; six studies mentioned the percentage of participants which used condoms, one excluded couples who used condoms and the remaining five articles did not mention the percentage of condom use. Finally, only five studies described the proportion of women with CIN I/ II/ III, whose partners participated in the studies.

The number of men who were partners of women with CIN, was 885. The mean age of the male participants was 35.18 years and the standard deviation was 3.47. The coefficient of variation was 9.8%. A total of 779 penile samples were obtained by brushing, and were tested by any HPV molecular assay; among them, 383 (49.1%) were HPV-positive. Ten out twelve studies (83.3%) demonstrated prevalence > 20%. A great difference regarding the HPV prevalence was observed between the studies, depending on the particular profile of the target group, on the method assay used and on the prevalence of the virus in the various geographical areas (Table 5). The lowest percentage (12.9%) was found by Martin-Ezquerra et al in Spain [17], whereas, the highest (86%) was described by de Rocha et al in Brazil [19].

In addition, among the studies, different HPV subtypes were identified, such as, 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 66, 68, 81 and 83 (see Table 5). According to the data of six studies, HPV 16 was the most frequent subtype [11, 15, 18,19,20, 22], whereas, in two other studies the subtypes 6 and 83 predominated [13, 21].

Finally, only five out of 12 studies have studied the concordance of HPV-subtyping between the couples [15, 17, 19, 21, 22]. Benevolo et al, reported that 42.8% of the couples, that were HPV-positive, harbored at least one identical subtype, including HPV 16, 51, 52, 53, 56 and 58 [15]. This percentage is lower than that described by Lopez-Diez et al, who has demonstrated that 62% of infected couples had at least one subtype in common [22]. In both studies, HPV 16 was detected in a high proportion of infected couples. Vargas et al also showed that 28% of the sexual partners shared at least one viral subtype (16, 51, 52, 54, 68, 73 and 81) [21], while Afonso et al demonstrated that 53.3% of the couples had the same subtype (HPV 16) [18]. de Lima-Rocha et al found that 56.5% of the couples had at least one common subtype (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31), whereas, absolute concordance was observed in only one case (4.3%) [19]. Furthermore, in the same study, the male partner had the same HR sub-types as their female sexual partner (HPV 16, 18, 31).

Discussion

HPV infection is common in asymptomatic men. In a systematic review of the literature, Dunne et al have shown that the prevalence of HPV infection in asymptomatic men ranges from 1.3–72.9% [24], while Smith et al have demonstrated that HPV prevalence among high-risk men (such as sexually transmitted infection clinic attendees, human immunodeficiency virus-positive males, male partners of women with HPV infection or abnormal cytology and men who have sex with men) was from 2 to 93% versus 1–84% in low-risk men [25,26,27]. In addition, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that, between 2013 and 2014, in the USA, the prevalence of genital HPV for men aged from 18 to 59 years old was 45%, while, 25% of men had HR genital HPV infection [28]. A recent meta-analysis revealed a prevalence of 49% of any type of HPV and 35% of HR-subtypes in men [29]. However, the real incidence and prevalence of HPV infection in asymptomatic men is difficult to estimate, due mainly to the silent behavior of this virus not only in men but also in women.

According to data from studies conducted in North and Latin America, genital HPV prevalence is indicated to be higher in men than in women [30,31,32]. A meta-analysis by de Sanjose et al has demonstrated that the overall HPV prevalence in women with normal cervical cytology was 10.4%; the highest percentages were observed in Africa (22.1%), Central America and Mexico (20.4%), Northern America (11.3%), Europe (8.1%), and Asia (8.0%) [33]. On the basis of these estimates, approximately 291 million women worldwide are carriers of HPV DNA, of whom 32% are infected with HPV 16 or 18, or both.

In the present systematic review, we have found that the mean prevalence of HPV infection, in male partners of women with CIN was 49.1%. Although HPV 16 was the most common subtype, many other subtypes (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 66, 68, 81 and 83) were also detected. An interesting finding was that none of the participants had any clinical signs indicating that this target group was a reservoir for the dissemination of the virus. Apart from the HPV detection, the subtyping is very important not only for epidemiological purposes but, also, for evaluating the oncogenic potential of new subtypes in order to establish an effective and safe vaccination program.

Despite the variety of methods for the diagnosis of HPV in men, investigation into the presence of the virus has not been consensual [34]. Unfortunately, the identification of the presence of HPV in men is far more difficult than in women, due to the smaller quantity of plane squamous non-keratinized mucosa of the male genital organ in relation to that of the female [35]. Diagnostic tools are peniscopy, biopsy and HPV DNA testing. Recent studies have demonstrated that even when carried out by experienced professionals, peniscopy has very low specificity, leading to unnecessary biopsies [36]. Today, the identification of HPV has been carried by molecular assays using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or hybrid capture; these methods are rapid, sensitive and easy to be performed [37,38,39,40]. Several of them are commercial, having the capacity not only to detect infection presence but also to characterize the different subtypes. Clinical specimens obtained using brushes from different anatomical sites can be directly tested for the presence of HPV DNA. Giuliano et al have shown that the optimal anatomical sites for detection of HPV are the penile shaft, the glans penis/coronal sulcus and the scrotum; specimens obtained from urethra and semen seem to have the lowest sensitivity [32]. However, sometimes, the detection of genital HPV is technically more complicated in men than in women because cells are more difficult to harvest from skin than from moist mucosal surface. Specimens, such as urine, are more easy to be obtained and to be tested for HPV presence. Neha Pathak et al, have demonstrated that HPV DNA testing of urine may be an alternative and an easier approach [41, 42].

According to the data of the studies included in this review, the use of condoms was limited. In addition, only a minority of participants were circumcised. Previous studies have demonstrated that constant condom use is associated with reduced prevalence of HPV [43]. On the other hand, circumcision seems to minimize the risk for HPV penile infection and in the case of men with multiple sexual partners, circumcision reduce the risk of cervical cancer in their sexual partners [44].

There is a question how to manage the male partners of women diagnosed with CIN. It is well known than men who are found positive for HPV, could be HPV negative after 12 months. This could be explained by the fact that the epithelial cells of the penile skin are more resistant to HPV infection than the cervical epithelium, the clearance rates differ by gender and the duration of HPV infection is shorter in men than in women [45]. Morales et al have shown that the median clearance time for any HPV subtype was 5.1 months (3.5–7.7), while the duration of the colonization was similar for oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV subtypes [46]. Also, Guiliano et al stated that the median clearance rate of any HPV subtype was 5.9 months, with no observed difference in clearance time between oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV subtypes; 75% of participants were negative for any HPV subtype after 12 months [47].

Summarizing the results of the studies included, healthy sexual male partners of women with CIN may be HR HPV-positive, maintaining the risk of viral transmission and consequently the risk of recontamination of their female partners. Therefore, when the male partners were found to be positive by a penile HPV test, they should be advised to undergo a clinical follow up as previously reported by Gupta et al [48]. In addition, the introduction of the 9-valent HPV vaccine, that includes the subtypes 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58, most of which were detected in the partners of women with CIN, combined with education regarding the prevention should limit the spread of the virus within couples [49, 50].

Limitations

The main limitations of this review are the differences between the characteristics among the participants and the different HPV DNA testing assays. Some studies have included regular and monogamous sexual partners, but others just regular partners. Some studies have included men who have been circumcised, which may alter the results since circumcision seems to protect men from HPV infection. Among the studies, the proportion of women with CIN I, CIN II and CIN III differed significantly, while sometimes the proportion was not mentioned. So, searching for correlation between HPV infection of male partner and the grade of CIN was not possible. Also, the studies have been held in different countries, where the prevalence of HPV infection varies in the general population. Finally, among the studies, various HPV DNA tests with different specificity were used for the detection of the virus, in addition, each study characterized specific subtypes.

Conclusion

Until now, there are not precise screening or surveillance guidelines for the management of partners of women with CIN. This population is frequently colonized by various HPV subtypes and therefore need to be screened in an effort to reduce the infection in both sexes. The screening test could include detection/identification of HPV subtypes by a molecular assay, followed by peniscopy only in the positive cases.

Given that the virus is associated with neoplastic lesions, these men are also at risk for HPV-related tumors (penile cancer etc). The introduction of vaccines could play an important role to the prevention and therapy. Prophylactic HPV vaccination (B-cell-mediated immunity) provides lifelong protection against subtypes included in the vaccine; therefore, a vaccination program for children of both sexes is counted to the primary prevention strategies and might reduce the HPV prevalence. On the other hand, therapeutic vaccines, based on an antigen-specific T-cell immunity are promising approaches for the treatment of already existing intracellular HPV infections and are under investigation.

Abbreviations

- ASCUS:

-

Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance

- CD:

-

Cervical dysplasia

- CDC:

-

Center for Control and Prevention

- CIN:

-

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

- GW:

-

Genital warts

- HPV:

-

Human Papillomavirus

- HR:

-

High risk

- HSIL:

-

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- LR:

-

Low-risk

- LSIL:

-

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- N/A:

-

Not available information in study

References

Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C, Murakami I. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25(Suppl 1):2–23.

Chesson HW, Ekwueme DU, Saraiya M, Dunne EF, Markowitz LE. The cost-effectiveness of male HPV vaccination in the United States. Vaccine. 2011;29(46):8443–50.

Abbas A, Yang G, Fakih M. Management of anal cancer in 2010. Part 1: overview, screening, and diagnosis. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24(4):364–9.

Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(6):518–27.

Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Muñoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(4):244–65.

Dunne EF, Nielson CM, Stone KM, Markowitz LE, Giuliano AR. Prevalence of HPV infection among men: a systematic review of the literature. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(8):1044–5.

Anderson LA, O'Rorke MA, Wilson R, Jamison J, Gavin AT, Northern Ireland HPV working group. HPV prevalence and type-distribution in cervical cancer and premalignant lesions of the cervix: a population-based study from Northern Ireland. J Med Virol. 2016;88(7):1262–70.

Zielinski GD, Bais AG, Helmerhorst TJ, Verheijen RH, de Schipper FA, Snijders PJ, et al. HPV testing and monitoring of women after treatment of CIN 3: review of the literature and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59(7):543–53.

McCaffery K, Waller J, Nazroo J, Wardle J. Social and psychological impact of HPV testing in cervical screening: a qualitative study. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(2):169–74.

Levine RU, Crum CP, Herman E, Silvers D, Ferenczy A, Richart RM. Cervical papilloma-virus infection and intraepithelial neoplasia: a study of male sexual partners. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64(1):16–20.

Bleeker M, Hogewoning CJ, Voorhorst FJ, van den Brule AJ, Berkhof J, Hesselink AT, et al. HPV-associated flat penile lesions in male of a non-STD hospital population: less frequent and smaller in size than in male sexual partners of women with CIN. Int J Cancer. 2005;113(1):36–41.

Rosenblatt C, Lucon AM, Pereyra EA, Pinotti JA, Arap S, Ruiz CA. HPV prevalence among partners of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;84(2):156–61.

Rombaldi RL, Serafini EP, Villa LL, Vanni AC, Baréa F, Frassini R, Xavier M, Paesi S. Infection with human papillomaviruses of sexual partners of women having cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39(2):177–87.

Giraldo P, Eleutério J Jr, Cavalcante DI, Gonçalves AK, Romão JA, Eleutério RM. The role of high-risk HPV-DNA testing in the male sexual partners of women with HPV-induced lesions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;137(1):88–91.

Benevolo M, Mottolese M, Marandino F, Carosi M, Diodoro MG, Sentinelli S, et al. HPV prevalence among healthy Italian male sexual partners of women with cervical HPV infection. J Med Virol. 2008;80(7):1275–81.

Guzman-Esquivel J, Martínez-Contreras A, Ramírez-Flores M, Jiménez Ceja LM, Delgado-Enciso I, Martínez-Garza S, et al. Association between human pappilomavirus in men and their sexual partners and uterine cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41(2):335–40.

Martin-Ezquerra G, Fuste P, Larrazabal F, Lloveras B, Fernandez-Casado A, Belosillo B, et al. Incidence of human papillomavirus infection in male sexual partners of women diagnosed with CIN II-III. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22(2):200–4.

Afonso L, Rocha WM, Carestiato FN, Dobao EA, Pesca LF, Passos MR, et al. Human papillomavirus infection among sexual partners attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46(6):533–8.

de Lima Rocha G, Faria FL, Gonçalves L, Souza Mdo C, Fernandes PÁ, Fernandes AP. Prevalence of DNA-HPV in male sexual partners of HPV-infected women and concordance of viral types in infected couples. Plos. 2012;7(7):e40988.

Rob F, Tachezy R, Pichlík T, Rob L, Kružicová Z, Hamšíková E, et al. High prevalence of genital HPV infection among long-term monogamous partners of women with cervical dysplasia or genital warts-another reason for HPV vaccination of boys. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12435.

Vargas H, Betancourt J, Sierra Y, Gómez S, Díaz L, Sánchez J, et al. Type-specific HPV concordance in a group of stable sexual partners from Bogota, Colombia. Mol Biol. 2016;5:170.

Lopez-Diez E, Pérez S, Iñarrea A, de la Orden A, Castro M, Almuster S, et al. Prevalence of concordance of high-risk papillomavirus infection in male sexual partners of women diagnosed with high grade cervical lesions. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35(5):273–7.

Weaver BA, Feng Q, Holmes KK, Kiviat N, Lee SK, Meyer C, et al. Evaluation of genital sites and sampling techniques for detection of human papillomavirus DNA in men. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(4):677–85.

Olesen TB, Sand FL, Rasmussen CL, Albieri V, Toft BG, Norrild B, Munk C, Kjær SK. Prevalence of human papillomavirus DNA and p16INK4a in penile cancer and penile intraepithelial neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):145-58.

Smith JS, Gilbert PA, Melendy A, Rana RK, Pimenta JM. Age-specific prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in males: a global review. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(6):540–52.

Ucciferri C, Tamburro M, Falasca K, Sammarco ML, Ripabelli G, Vecchiet J. Prevalence of anal, oral, penile and urethral human papillomavirus in HIV infected and HIV uninfected men who have sex with men. J Med Virol. 2018;90(2):358–66.

Sammarco ML, Ucciferri C, Tamburro M, Falasca K, Ripabelli G, Vecchiet J. High prevalence of human papillomavirus type 58 in HIV infected men who have sex with men: a preliminary report in Central Italy. J Med Virol. 2016;88(5):911–4.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov.

Rodríguez-Álvarez MI, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Husein-El Ahmed H, Albendín-García L, Gómez-Salgado J, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Prevalence and risk factors of human papillomavirus in male patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):E2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102210.

Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813–9.

Herrero R, Castle PE, Schiffman M, Bratti MC, Hildesheim A, Morales J, et al. Epidemiologic profile of type-specific human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1796–807.

Giuliano AR, Nielson CM, Flores R, Dunne EF, Abrahamsen M, Papenfuss MR, et al. The optimal anatomic sites for sampling heterosexual men for human papillomavirus (HPV) detection: the HPV detection in men study. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1146–52.

de Sanjosé S, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Clifford G, Bruni L, Muñoz N, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(7):453–9.

Nicolau SM, Camargo CG, Stávale JN, Castelo A, Dôres GB, Lörincz A, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA detection in male sexual partners of women with genital human papillomavirus infection. Urology. 2005;65(2):251–5.

Svare EI, Kjaer SK, Worm AM, Osterlind A, Meijer CJ, van den Brule AJ. Risk factors for genital HPV DNA in men resemble those found in women: a study of male attendees at a Danish STD clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(3):215–8.

Kumar B, Gupta S. The acetowhite test in genital human papillomavirus infection in men: what does it add? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(1):27–9.

Zhong Q, Li K, Chen D, Wang H, Lin Q, Liu W. Rapid detection and subtyping of human papillomaviruses in condyloma acuminatum using loop-mediated isothermal amplification with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. Br J Biomed Sci. 2018;75(3):110–5.

Klaassen CH, Prinsen CF, de Valk HA, Horrevorts AM, Jeunink MA, Thunnissen FB. DNA microarray format for detection and subtyping of human papillomavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(5):2152–60.

Ramael M, Van Steelandt H, Stuyven G, Van Steenkiste M, Degroote J. Detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) genomes by the primed in situ (PRINS) labelling technique. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195(12):801–7.

Livingstone DM, Rohatensky M, Mintchev P, Nakoneshny SC, Demetrick DJ, van Marle G, et al. Loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for the detection and subtyping of human papillomaviruses (HPV) in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC). J Clin Virol. 2016;75:37–41.

Pathak N, Dodds J, Zamora J, Khan K. Accuracy of urinary human papillomavirus testing for presence of cervical HPV: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g5264.

Pathak N, Dodds J, Zamora J. Could urine testing be the future of cervical cancer screening? Womens Health (Lond). 2015;11(3):265–7.

Repp KK, Nielson CM, Fu R, Schafer S, Lazcano-Ponce E, Salmerón J, et al. Male human papillomavirus prevalence and association with condom use in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(8):1287–93.

Castellsagué X, Bosch FX, Muñoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV, de Sanjose S, et al. Male circumcision, penile human papillomavirus infection, and cervical cancer in female partners. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1105–12.

Giuliano AR, Nyitray AG, Kreimer AR, Pierce Campbell CM, Goodman MT, Sudenga SL, et al. EUROGIN 2014 roadmap: differences in human papillomavirus infection natural history, transmission and human papillomavirus-related cancer incidence by gender and anatomic site of infection. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(12):2752–60.

Morales R, Parada R, Giuliano AR, Cruz A, Castellsagué X, Salmerón J, et al. HPV in female partners increases risk of incident HPV infection acquisition in heterosexual men in rural Central Mexico. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2012;21(11):1956–65.

Giuliano AR, Lu B, Nielson CM, Flores R, Papenfuss MR, Lee JH, et al. Age-specific prevalence, incidence, and duration of human papillomavirus infections in a cohort of 290 US men. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(6):827–35.

Gupta A, Arora R, Gupta S, Prusty BK, Kailash U, Batra S, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA in urine samples of women with or without cervical cancer and their male partners compared with simultaneously collected cervical/penile smear or biopsy specimens. J Clin Virol. 2006;37(3):190–4.

Harder T, Wichmann O, Klug SJ, van der Sande MAB, Wiese-Posselt M. Efficacy, effectiveness and safety of vaccination against human papillomavirus in males: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):110.

Chelimo C, Wouldes TA, Cameron LD, Elwood JM. Risk factors for and prevention of human papillomaviruses (HPV), genital warts and cervical cancer. J Inf Secur. 2013;66(3):207–17.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS conducted designing the study, literature search, reviewed literature, extracted data from the literature and prepared a draft of the manuscript. SF, MM and KP critically reviewed the manuscript. EP conceived the study, participated in the designing of the study and in the preparation of the final draft.. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Skoulakis, A., Fountas, S., Mantzana-Peteinelli, M. et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus and subtype distribution in male partners of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN): a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 19, 192 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3805-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3805-x