Abstract

Background

TB outbreaking in schools is extremely complex, and presents a major challenge for public health. Understanding the knowledge, attitudes and practices among student TB patients in such settings is fundamental when it comes to decreasing future TB cases. The objective of this study was to develop a Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Questionnaire among Student Tuberculosis Patients (STBP-KAPQ), and evaluate its psychometric properties.

Methods

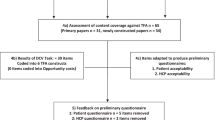

This study was conducted in three stages: item construction, pilot testing in 10 student TB patients and psychometric testing, including reliability and validity. The item pool for the questionnaire was compiled from literature review and early individual interviews. The questionnaire items were evaluated by the Delphi method based on 12 experts. Reliability and validity were assessed using student TB patients (n = 416) and healthy students (n = 208). Reliability was examined with internal consistency reliability and test-retest reliability. Content validity was calculated by content validity index (CVI); Construct validity was examined using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA); The Public Tuberculosis Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Questionnaire (PTB-KAPQ) was applied to evaluate criterion validity; As concerning discriminant validity, T-test was performed.

Results

The final STBP-KAPQ consisted of three dimensions and 25 items. Cronbach’s α coefficient and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.817 and 0.765, respectively. Content validity index (CVI) was 0.962. Seven common factors were extracted by principal factor analysis and varimax rotation, with a cumulative contribution of 66.253%. The resulting CFA model of the STBP-KAPQ exhibited an appropriate model fit (χ2/df = 1.74, RMSEA = 0.082, CFI = 0.923, NNFI = 0.962). STBP-KAPQ and PTB-KAPQ had a strong correlation in the knowledge part, and the correlation coefficient was 0.606 (p < 0.05). Discriminant validity was supported through a significant difference between student TB patients and healthy students across all domains (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

An instrument, “Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Questionnaire among Student Tuberculosis Patients (STBP-KAPQ)” was developed. Psychometric testing indicated that it had adequate validity and reliability for use in KAP researches with student TB patients in China. The new tool might help public health researchers evaluate the level of KAP in student TB patients, and it could also be used to examine the effects of TB health education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since 1970, Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) research has been the primary educational intervention strategy for tuberculosis (TB) control worldwide [1]. Several studies had shown that, the level of KAP in individuals was linked to efficient management of illness, response to medical treatment, and promotion of one’s own health [2,3,4,5]. Lower KAP level had been one of the main indicators of poor health, inefficient health care use, the decrease of the disease screening rate, and maladaptive disease preventive behavior [6,7,8].

Tuberculosis (TB) has existed for millennia and remains a major global health problem. It caused ill-health in millions of people each year and was one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide, ranking above HIV/AIDS as one of the leading causes of death from an infectious disease [9]. Globally in 2015, there was an estimated 10.4 million incident cases of TB, of these, China, India and Indonesia alone accounted for 45% [9]. In Shaanxi Province of China, from 2011 to 2015, the number of student TB patients was always higher than 1300 annually, accounted for 6.17-6.78% of total TB cases [10, 11]. At the same time, TB transmission was ongoing in schools. A total of 44 student TB patients were found and diagnosed during TB outbreak in a middle school in Jinan, Shandong Province from April 2013 to November 2014 [12]. A military academy in Guangdong Province cumulatively reported 44 cases of TB from January to July in 2014 [13]. From February to April in 2015, 11 student TB patients were found in a middle school in Liaoyang, Liaoning Province [14]. Even in many lower TB burden countries, such as Britain and the United States, epidemic of student TB has also been reported [15, 16].

TB outbreaking in schools is extremely complex, and presents a major challenge for global public health, and the outbreak highlights the need for innovative TB prevention and control strategies in such settings. As most students are from a high risk population group, they need some prevention strategies including prompt referral of symptomatic cases to TB services, and to be raised awareness about TB. The survey of Ridzon R showed that students who have significantly higher knowledge scores were more likely to find TB timely [17]. Donald et al. [18] pointed out that TB education among teenagers could help patients successfully complete the TB treatment. Chen et al. [19] reported that students had delayed diagnosis due to the lack of TB prevention knowledge. All of these suggest that it is necessary to evaluate the level of KAP in student TB patients, which can help us carry out the targeted health education and prevent future outbreaks.

Overview of existing measurement instruments

There are many ways to assess the level of KAP in student TB patients, and self-administration of questionnaire is the most common approach. Iranish scholar Fatemah et al. [20] and Turkish scholar Semiha et al. [21] investigated the KAP level in student TB patients using a questionnaire with a description of composition contents only; Marguerite et al. [22] conducted a cross-sectional survey about TB KAP in health professional students throughout California area, and the questionnaire was only assessed with the clarity and face validity; Roman scholar Mushta et al. [23] carried out a survey of TB KAP level in medical students and the general population, respectively, a pilot test was only conducted for their questionnaires, and the results had not been reported; Daniel et al. [24] investigated the TB KAP level of a community in Ethiopia, Somalia, but the reliability and validity of the questionnaire had not been estimated.

In China, the questionnaire used most widely is the public TB KAP questionnaire (PTB-KAPQ) [25]. Qingdao University has developed a TB KAP questionnaire for university students in 2012 [26]. However, these instruments are generic, none of them were specifically designed for assessing student TB patients’ KAP level. In terms of TB knowledge, student TB patients should understand basic symptoms of TB, treatment process, the correct handling of the side effects of drugs, the free treatment policy and principles of chemical treatment of TB (early, joint, right-amount, regular, whole-journey). Regard to TB attitudes, they should learn that hiding their disease is not correct, and it is necessary to remind close contacts of an inspection. Behavior is especially important, we need to know whether student TB patients have the high-risk behaviors in TB spread, such as not wearing masks in public, coughing and sneezing in front of others.

This study was aimed at developing Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) Questionnaire among Student Tuberculosis (TB) Patients (STBP-KAPQ), and evaluated its psychometric properties. The questionnaire will help TB medical professional identify not only student TB patients with poor level of KAP, but also help them to design and implement targeted interventions to improve the level of KAP.

Framework for the development of STBP-KAPQ

“KAP theory” is a health behavior change theory, proposed by western scholars in the 1960s [27], in which the changes of human behavior are divided into three successive processes: the acquisition of knowledge, the generation of attitudes and the formation of behavior. The theory presents the progressive relationship among knowledge, attitudes and behavior as follows: knowledge is the foundation of behavior change, and belief and attitudes are the driving force of behavior change. “Health belief model” was put forward in the 1950s [28], which pointed out that the formation of health belief played a key role for people to accept the persuasion, change the bad behavior, and adopt the healthy behavior. Therefore, the “KAP theory” and “Health belief model” were adopted to guide the development of the STBP-KAPQ.

Methods

Questionnaire development procedures

Phase 1: Item construction

A. Item pool's three sources:

-

(1)

WHO “A guide to develop KAP surveys” (World Health Organization 2008) [29]; Collecting as many terms as possible that were considered essential knowledge for student TB patients by referring to books on health, health-related magazines, and leaflets distributed by hospitals and government institutes, such as “China TB prevention and control work guide (2008 edition)”, “school TB prevention and control work manual”.

-

(2)

A review of published research on KAP definitions and concepts, and on its measurement.

-

(3)

Early interview of the research team:

Following the principle of informed consent, confidentiality and voluntary, the research team once performed an individual in-depth interview with 17 college students in 2013 and 22 high school students in 2015 after the TB epidemic emerged. The interview topics included general information, the medical behavior, medication compliance, knowledge about the TB control, the difficulties during treatment, the psychological burden after TB diagnosis and so on.

B. Two-round expert consultation

Participants

According to the inclusion criteria: (a) engaging in the TB prevention and control, clinical diagnosis and treatment, health education and school TB control management; (b) working for more than 10 years; (c) the subtropical high titles and above. In the Delphi method, 12 experts (4 TB prevention and control experts, 1 public health professionals, 2 clinical doctors, 2 health education and health promotion experts, 3 school TB prevention and control of management specialists), were recruited. They were from the Ministry of Health, the Chinese Center For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Provincial CDC and the schools.

Delphi round 1

Round 1 of the Delphi sent a copy of the 23-items questionnaire to the expert panel (n = 12) by e-mail. Experts voted on a five-point scale (0 to 4, where 0 = very unimportant and 4 = very important) showing the extent to which they thought each of the 23 questions should be included in the S-TBKAPQ. Experts were asked to return within two weeks, and a reminder e-mail was sent if no response had been made after one week.

Delphi round 2

In Round 2 of the Delphi, responses of round 1 were collated and the questionnaire was amended as appropriate, then a amended questionnaire was sent to the same expert panel (n = 12) via e-mail. Experts were asked to re-rate the questions on the same five-point scale in light of the results and comments from Round 1. Experts were still asked to return within two weeks, and a reminder e-mail was also sent if there was no response after one week.

Evaluation index

-

a.

Positive coefficient: the positive coefficient refers to the extent of experts’ concern about the research, evaluated by the recovery rate of the questionnaire. It is generally believed that the recovery rate of 50% is the lowest proportion can be analyzed, 60% is a good result, and 70% is a rather good result [30].

-

b.

The authoritative coefficient: the authoritative coefficient (Cr) was generally decided by two factors: the judgment criterion (Ca) and the familiarity (Cs). The calculation formula of authoritative coefficient was as follows: Cr = (Ca + Cs) /2, the greater the Cr, the greater the degree of authority [31].

C. The screening of items

After each round of expert consultation, the importance of expert’s judgment to items was computed. According to a five-point scale (0 to 4, where 0 = completely unimportant and 4 = completely important), experts were required to give the corresponding score in terms of the importance of items, and then the items were screened according to the central tendency and dispersion degree.

The central tendency was evaluated by the item selection rate (The item selection rate = the number of experts who rated items with a score of 3 (important) or 4 (very important) /the total number of experts× 100%). If the item selection rate was < 80%, it would be deleted [32]. The discrete degree was measured using the coefficient of variation (the ratio of standard deviation and arithmetic average of the item importance score). If the variable coefficient was ≥0.2, it would be deleted [32].

The initial draft of the questionnaire was produced through above procedures.

Phase 2: Pilot study

A similar sample of 10 student TB patients from Xi’an Chest Hospital enrolled in the pilot study, including two junior high school students, four senior high school students and four college students. They were asked to complete the initial draft of the questionnaire, and afterwards they were asked to provide their comments about problems in completing it, including whether it was clear and understandable, and also whether the content was complete and relevant. After these producers, the final version of the instrument to test validity and reliability was created.

Phase 3: The test of validity and reliability

Participants

The sample size recommended is 5 to 10 participants per item. As the number of the items was intended to be 25, a sample size estimated was 125 to 250 [33]. It is widely acknowledged that at least 100 samples are required, in order to establish an accurate inference in exploratory factor analysis (EFA) [34]. In addition, in order to evaluate confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), a minimum sample size of 200 is needed to gain reliable results [35]. Considering a 20% non-response rate, the minimum sample size was set at 390 participants.

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria: (a) who were middle school and college students; (b) with a confirmed TB; (c) who was reported in the TB registry system; (d) whose treatment was undergoing or complete; and (e) who was voluntary to participate in the study; (f) patients who suffered from other serious diseases or had cognitive impairment were excluded from the study. 416 student TB patients by convenience sample (including 64 junior high school, 129 high school students and 223 college students) were recruited, which were randomly divided into two parts (N1 = 206, N2 = 210), the former for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the latter was used in the confirmatory factor analysis(CFA), respectively. To distinguish clearly between two different types about measuring indexes, the sample size of two groups recommended are equal [36], so 208 healthy students were recruited as a comparison group to assess the discriminant validity, matched by sex and grade, in similar proportions as the 206 student TB patients of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA). It’s requested that the sample size in the test-retest reliability is not fewer than one over ten of the total research objects, and the larger the sample size the better [37], so 50 student TB patients were selected for evaluation of the test-retest reliability.

Measures

The aspects of reliability (internal consistency reliability, re-test reliability,) and validity (content validity, construct validity, criterion validity, discriminant validity) of the questionnaire were tested.

Data collection

The research team who collected the questionnaires was made up of five trained researchers. Except for the chairman, two members as a group went to the target locations respectively. Written informed content was obtained prior to the survey. We handed out the questionnaires to participants face-to-face and one-to-one, and withdrawed them on the spot. At this stage, explanations were necessary to ensure that the participants understood the purpose and importance of the study. With regard to respondents who had lower reading comprehension, researchers would read the instructions and questions without any additional interpretation or explanation. In order to improve the response rates, all participants received a beautiful notebook or a red packet as reward before the survey. Participants independently completed the questionnaire, and all the questionnaires were anonymous. Questionnaires with missing response ≧ 20% or apparently unreliable responses were considered ineligible and would be removed before analysis, (for instance, the choices in the questionnaire were all the same, with no changes; or the logic of the answer was chaotic, inconsistent and contradictory with itself), in order to ensure the quality of data and the rationality of statistical results.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS18.0 and AMOS 18.0 software. Descriptive statistics was used to outline the demographic characteristics. Cronbach’α coefficient was computed for internal consistency reliability, and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate test-retest reliability. Content validity was measured by content validity index (CVI). Construct validity was examined by exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). For criterion validity of the STBP-KAPQ, a Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated, and T-test was employed for a group comparison between the student TB patients and healthy students, providing an evidence for discriminant validity.

Results

Expert characteristics and the result of consultation

The average age of the experts was 49.83 ± 10.85, and the average serving time was 15.25 ± 7.97 years. Experts in title of a senior professional post accounted for 75%. The positive coefficient was 100%, and the authoritative coefficient of this study was 0.866.

The result of item screening

Five items were added after the first round expert consultation, including the knowledge items associated with TB examination, the consequences of drug withdrawal,the drug adverse reactions, the attitudes item about spreading TB knowledge as a volunteer, and the behavior item of what to do with the sputum. Three attitudes items associated with TB prevention and control were removed. There were 25 items in the second round, which were judged again by the experts, and the initial draft of the questionnaire was produced.

The result of pilot study

They completed the initial draft questionnaire with no item non-response within 7–15 min. The instrument was considered not long and easy to complete. All items were considered relevant to the aim of study, and no suggestions were made regarding the exclusion of any items or the addition of new items. Fuzzy expression statements of some items were revised, in case of causing unease.

The result of the STBP-KAPQ

According to the opinions of experts and 10 student TB patients in the pilot study, a total of 25 preliminary items were selected, reflecting four constructs of STBP-KAPQ as follows: general demographic information, TB knowledge, attitudes and behavior related to the TB prevention and control. One point was given if there was a right selection in the knowledge part, and items of the attitudes (two items not scoring) and practices were stated as propositions with a labeled five-point scale (1 = very disagreed, 5 = very agreed) and a four-point scale (1 = never, 4 = always), respectively. Some of the items were reverse scoring. A final version of the questionnaire was created to evaluate validity and reliability.

The results of validity and reliability

Participant characteristics

Within the 416 student TB patients (210 college students, 206 middle school students), 416 questionnaires were distributed to student TB patients, only 408 of the recovered questionnaires were valid, and the recovery rate was 98.72%. Moreover, 67.5% of the student TB patients were males, and more than half of them were college students (Table 1). For 208 healthy students (108 college students, 100 middle school students), 208 questionnaires were distributed and withdrawed, all of them were valid, so the recovery rate was 100%. The healthy students in this study were recruited by matching sex and grade to the group of student TB patients. Chi-squared test, T-test, analyses of variance (ANOVA) and Mann-Whitney U test were conducted to examine the characteristics differences between the student TB patients group and the healthy one. As expected, there were no significant differences observed between the two groups in terms of gender (p > 0.05), grade (p > 0.05), personal monthly cost (p > 0.05), TB contact history (p > 0.05) and TB healthy education (p > 0.05).

The result of reliability

The Cronbach’α coefficient was 0.817, ranging from 0.793 to 0.817, and it was slightly changed once one item was deleted from the three sections (knowledge, attitudes and behaviors). To evaluate test–retest reliability, 50 student TB patients were remeasured after 2 weeks, and the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.765.

The result of validity

Construct validity

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were used to explore the appropriate construct of STBP-KAPQ.

The result of exploratory factor analysis

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used prior to factor analysis, to ensure that the data from student TB patients were appropriate for conducting factor analysis. The factor analysis was based on the following criteria: (a) A bigger KMO value: KMO value should be between 0 and 1, the greater its value the better factor analysis results. If KMO value is < 0.5, it is unsuitable for factor analysis. (b) Significant Bartlett ball test (p < 0.05), which was used to examine whether the factor was independent. In the present study, the KMO value was 0.687, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was found to be significant (χ2 = 81,797.730, p < 0.05). Therefore, the exploratory factor analysis could be conducted on this study.

Principal component analysis with biggest variance orthogonal rotation was applied to determine the underlying factor structure of the 25 items. The factor loading of all questionnaire items were not present cross, and the factor loading values were more than 0.4, ranging from 0.428 to 0.924 (Table 2). Since eigenvalues were more than 1, seven meaningful factors were extracted, which explained 66.253% of the total variance (Table 3). Factor 1 (adverse drug reaction) was related to side effects of drug, and it had the maximum contribution (21.541%). Factor 2 (standard treatment) was associated with TB cure. Factor 3 (active notification) showed the importance of TB notification, and factor 4 (positive behavior) was associated with the positive life behavior of TB. Factor 5 (regular medication) was connected with the entire regular medication, factor 6 (active prevention) was associated with active prevention of TB, and factor 7 (core knowledge) was about the TB understanding. The result of scree plot also illustrated that the seven factors should be extracted (Fig. 1).

The result of confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was used to establish the most appropriate factor structure of the STBP-KAPQ, model fit was considered acceptable if χ2/df < 2, comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.9, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06 [38,39,40]. The 7-factor model was found to fit the data much better with a smaller model χ2/df statistics (χ2/df = 1.74) and stronger model fit indexes (CFI = 0.923, RMSEA = 0.082), than the original model (CFI = 0.802). As expected, the STBP-KAPQ with 7-factor structure model was an acceptable fit model.

Content validity

Content validity reflects the representativeness of the questionnaire items. The higher the content validity index is, the better item’s representativeness is. In this study, the content validity index was calculated by the proportion of the items with a rating of 3 or 4 by all experts. After evaluated by above-mentioned 12 experts, the content validity index was 0.962, which achieved the criterion for content validity, showing that the questionnaire items were accurate and comprehensive, and it covered all TB-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors that the student TB patients should learn.

Criterion validity

To test criterion validity of the STBP-KAPQ, The Public Tuberculosis Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Questionnaire (PTB-KAPQ) was used as a calibration standard questionnaire. Through Spearman analysis, the correlation coefficient between STBP-KAPQ and the PTB-KAPQ was 0.464 (p < 0.05), and there was a strongest correlation between the knowledge section and the PTB-KAPQ questionnaire (r = 0.606, p < 0.01). Moreover, there was a weaker correlation between attitudes, behavior sections and the PTB-KAPQ (Table 4).

Discriminant validity

For student TB patients, the mean (SD) scores for knowledge, attitudes and practices were 14.49 (1.850), 12.06 (1.376) and 20.40 (4.282), respectively. Healthy students indicated a lower mean (SD) score, which were 13.31 (1.740), 11.51 (1.630), 19.28 (4.957), respectively. There was a significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, we produced a 25-item STBP-KAPQ and showed that STBP-KAPQ was fairly consistent, reliable and valid. The STBP-KAPQ is the first measurement fitting situations of student TB patients in China.

The evaluation of reliability

Cronbach’α coefficient reflects the internal consistency of questionnaire. In general, Cronbach’α coefficient between 0.65-0.70 is the minimum acceptable value, 0.70-0.80 is rather good, and 0.80-0.90 is the best. Our results showed that the Cronbach’α coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.817, revealing that STBP-KAPQ had a good internal consistency reliability. For a new development of the measurement tool, it is believed that the retest reliability need to be more than 0.7. The retest correlation coefficient of our study was 0.765, revealing that the retest reliability of questionnaire was up to the requirements of psychological measurement, showing a good stability.

The evaluation of validity

Our results showed that the content validity index was 0.927, consistent with the requirement of a content validity index of at least 0.8, suggesting that the items could well reflect the KAP condition in student TB patients. In general, if the cumulative contribution rate above 40%, and each item on the corresponding factor owns enough loading (> 0.4), the factor is acceptable and the relationship between the item and factor is meaningful [41]. Our study adopted the principal component factor analysis method, and seven common factors were extracted. The cumulative contribution rate was 66.253%, and the corresponding factor loading of each item was > 0.4, revealing that each item in the common factor distribution conformed to the theoretical construction of questionnaire. In confirmatory factor analysis, the χ2/df was 1.74, the comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.923, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.082. The fitting indexes of the model reached significant level, therefore, the modified 7-factor model was the final model. The results of confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory factor analysis displayed that the questionnaire had reasonable construct validity.

In the present study, we used the Public Tuberculosis Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Questionnaire (PTB-KAPQ) as the criterion of STBP-KAPQ. Based on the analysis of criterion validity, there was a correlation between two questionnaires (r = 0.464, p < 0.05). The section of knowledge was highly related with the public questionnaire (r = 0.606, p < 0.01), but the sections of attitudes and practices exhibited a weaker correlation with the public questionnaire. This finding was consistent with our prediction. Our questionnaire aimed to develop for the student TB patients, leading to some different emphasis on the specificity of KAP level. For example, in the section of attitudes, we tended to evaluate whether student TB patients were willing to tell the teacher the situation of their sickness, to have an inspection, and to initiatively expand TB knowledge. In the behavior section, considering that the treatment of anti-TB needs at least 6 months [42], and there are more side effects, we added some items in our questionnaire, such as whether they would countercheck on time; decreased the times of drug or stopped taking medicine on their own. These contents were not covered in the PTB-KAPQ. Therefore, although this questionnaire was consistent with the PTB-KAPQ, they were not exactly the same. This prompted the specificity and uniqueness of STBP-KAPQ, and it also reflected the necessity to develop this questionnaire.

To evaluate the discriminant validity of STBP-KAPQ, we examined the discriminability of STBP-KAPQ in student TB patients and healthy students. Our results revealed that significant difference existed between the two groups on the sections of KAP. In terms of knowledge level, as expected, the scores of healthy students were significantly lower than those of student TB patients (p < 0.05), which was consistent with the 2006 public TB KAP survey conducted by Chinese CDC [43]. Here is the probable reason that students are generally more active to learn TB prevention and control knowledge after sick, more eager to figure out what TB is, while healthy students think TB is far away from themselves, so they don’t have a high enthusiasm to understand TB. In the attitudes and practices sections, the scores of students TB patients were higher than those of healthy students (p < 0.05). The reason may be student TB patients have set up the healthy attitudes and behavior in the standardized treatment, and they have learnt about how to promote the recovery of the disease. However, healthy students don’t have relevant consciousness about these without an experience of attack by TB, which were consistent with the survey results of Yang Yunbin [44].

Conclusion

An instrument, which may be useful as an easy-to-use self-report measure of student TB patients’ KAP towards TB, was developed and tested in our study. The analyses of reliability and validity demonstrated the strong psychometric properties of the STBP-KAPQ. The STBP-KAPQ supplements the limitations of current available TB KAP measures. Public health professionals can use the STBP-KAPQ to identify KAP level among student TB patients. The data may be used as the basis to improve TB prevention and control.

Limitations

Student TB patients were recruited using convenience sampling from the registry system of Shaanxi Provincial Institute for Tuberculosis Control and Prevention, and it was likely that patients not in the system were excluded, whose KAP was more scarce. The sample collection of this study only covered Shaanxi Province, taking this into consideration, future studies of this instrument will have to ensure the representativeness of study samples with diverse provinces and regions.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Chinese Center For Disease Control and Prevention

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- CVI:

-

Content validity index

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, attitudes and practices

- KMO:

-

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

- NNFI:

-

non-normed fit index

- RMSEA:

-

Root-Meta-Square Error of Approximation

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kempinski R, Krasnik A. Prevention of arteriosclerotic heart disease. An epidemiological study of knowledge,attitudes and practices in a community in Israle. Ugeskr Laeger. 1974;136:1931–8.

Suleiman M, Sahal N, Sodemann M, Elsony A. Tuberculosis awareness in Gezira, Sudan: knowledge, attitude and practice case–control survey. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20:120–9.

Khalil A, Abdalrahim M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards prevention and early detection of chronic kidney disease. Int Nurs Rev. 2014;61:237–45.

Matsumoto-Takahashi EL, Tongol-Rivera P. Patient knowledge on malaria symptoms is a key to promoting universal access of patients to effective malaria treatment in Palawan, the Philippines. PLoS One. 2015;10

Masud R, Abu S, Reazul K, Nurul I, et al. Assessment of knowledge regarding TB among non-medical university students in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:716.

Bansal AB, Pakhare AP, Kapoor N, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices related to cervical cancer among adult women: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. J Na Sci Biol Med. 2015;6:324–8.

Teran CC, Gorena UD, Gonzalez BC, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on HIV/AIDS and prevalence of HIV in the general population of Sucre. Braz J Infect Dis. 2015;19:369–75.

Francisco GS, Jay CB, Daniel BJ, Larry JS, et al. Treating cardiovascular disease with antimicrobial agents: a survey of knowledge, attitudes, and practices among physicians in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:171–6.

World Health. Organization (2016), Global TB Report. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

Chinese Center For Disease Control and Prevention. 2013 Chinese TB test report. Beijing: Chinese Center or Disease Control and Prevention 2013; 2013.

Chinese Center For Disease Control and Prevention (2014). Chinese TB test report. Beijing: Chinese Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2014.

Wang MH, Cao YM, Wang XT, Zhang MY, Yang YJ. Epidemiological survey of tuberculosis outbreak in a middle school in Jinan. Chin J Sch Health. 2016;37:8. Chinese

Yu DX, Liu JW. Epidemiological survey on a tuberculosis outbreak in a military academy. Mod Prev Med. 2016;43(6):1124-6. Chinese.

Zheng J. Investigation and its control measures on outbreak of the general level of tuberculosis. China Trop Med. 2016;16(2):184-5. Chinese.

Abubakar I, Matthews T, Harmer D, Okereke E, et al. Assessing an outbreak of tuberculosis in an English college population. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:976–90.

Ridzon R, Kent JH, Valway S, Weismuller P, et al. Outbreak of drug resistant tuberculosis with second-generation transmission in a high school in California. J Pediatr. 1997;131:863–8.

Ridzon R, Kent JH, Valway S, et al. Outbreak of drug resistant tuberculosis with second-generation transmission in a high school in California. J Pediatr. 1997;131:863–8.

Donald E, Morisky SD, Sc MC, et al. Behavioral Interventions for the Control of Tuberculosis Among Adolescents. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(6):568-74.

Chen W. Analysis of 2008-2012 national student characteristics of the tuberculosis epidemic. Chin J Prey Phthisiol. 2013;35:949–54. Chinese

Fatemah B, Golnaz M, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding tuberculosis among final year students in Yazd, Central Iran. J Epidemiol Global Health. 2014;4:81–5.

Semiha A, Gulay G, et al. Knowledge of and attitudes toward tuberculosis of Turkish nursingand midwifery students. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31:774–9.

Marguerite J, Shawn H, Helene H, et al. A survey of health professions students for knowledge, attitudes, and confidence about tuberculosis. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:219.

Mushta MU, Majrooh MA, Ahmad W, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding tuberculosis in two districts of Punjab, Pakistan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:303–10.

Daniel T, Girmay M, Mengistu L. Community knowledge, attitude, and practices towards tuberculosis in Shinile town, Somaliregional state, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:804.

Yu BZ, Yuan YL, Zhang TJ. Jilin province public TB prevention and control knowledge, belief and practice survey. Chin Health Eng. 2014;13:400–2. Chinese

Wang WW. Qingdao city high school students' knowledge, attitude and behavior for tuberculosis. Qingdao University. 2012. Chinese.

Ross J, Smith DP. Korea-trends in 4 National Kap Surveys, 1964-67. Stud Fam Plan. 1969;43:6–11.

Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:328–35.

World Health Organization. Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control: a guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. Geneva: World Health Organization WHO/HTM/STB/2008.46; 2008.

Rao Y, Feng ZX, Shao RY, et al. Development of the index system for performance appraisal of head nurses. Chin J Nurs. 2011;46(6):533. Chinese

Chen SJ. Chinese. In: Research on contextual performance model-based on empirical study of mid-level managers in high-tech enterprises: China, Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House, 2010.

Sun ZQ. Medical statistics. 3rd ed. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2011. Chinese

Lu TY. The study of Pittsburgh sleep scale measurement features and least important difference value. Trad Chin Med Univ Guangzhou. 2012; Chinese

Gaskin CJ, Happell B. On exploratory factor analysis: a review of recent evidence, an assessment of current practice, and recommendations for future use. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(3):511–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.10.005. PMID: 24183474

Hancock GR, Mueller RO, Cudeck R, du Toit S. Structural equation modeling: present and future—a Festschrift in honor of Karl Jöreskog. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International; 2001.

Ishikawa NM, Thuler LC, Giglio AG, Derchain SF, et al. Validation of the Portuguese (FACT-F) version of functional assessment of cancer therapy-fatigue in Brazilian cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:481.

Wu ML. SPSS Statistical Application Practice. Beijing: Science Press; 2003. p. 112–9.

Mueller RO. Basic principles of structural equation modeling: an introduction to LISREL and EQS. New York: Springer; 1996.

Yu, C.Y. Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcomes. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles. 2002.

Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55.

Swisher LL, Beckstead JW, Bebeau MJ. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis using a professional role orientation inventory as an example. Phys Ther. 2004;84:784–99.

Li Y, John E, Shenglan T, Daikun L. Factors associated with patient, and diagnostic delays in Chinese TB patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:156.

Tian BC, Meng XP, Lv SH, et al. The survey of national public TB knowledge core information in 2006. Chin Health Educ. 2008;6:409–12. Chinese

Yang YB. Analysis of tuberculosis epidemic characteristics and awareness in students Yunnan province from 2005 to 2014. Kunming Medical University. 2015. Chinese.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to the invaluable contribution of the participants of the study. We are grateful to kind support and assistance as well as guidance from Shaanxi Provincial Institute for Tuberculosis Control and Prevention. We would also like to thank Xi’an Chest Hospital and Shaanxi Province Tuberculosis Hospital for their kind support in data collection.

Availability of data and material

The data will not be shared in order to protect the participants’ anonymity.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science Foundation of China--the construction and application of the University student’s management system of tuberculosis prevention and control and information system based on GIS (71373203). The fund supported us to complete the study design, data collection, drafting and translating of the manuscript. Research on the Construction and Application of Management Model and Information Platform of Tuberculosis Patients Based on Adaptation Theory (7177031453).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YHF: conceived the study, participated in design and coordination, performed the data collection, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. SRZ: participated in design, supervised the study development, helped to draft the manuscript and made critical revision to the paper. YL and YLL performed data collection, data analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. THZ: participated in design and coordination, gave administrative, technical and material support. WPL: participated in the design, conducted quality control and assured completion of study procedures and data collection. HLJ: participated in the data copying and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Xi’an Jiaotong University, and Shaanxi Provincial Institute for Tuberculosis Control and Prevention (Letter Number:2017-518), and it was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were middle school and college students, written informed content was obtained from them or their parents (16>) prior to the survey.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Y., Zhang, S., Li, Y. et al. Development and psychometric testing of the Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) questionnaire among student Tuberculosis (TB) Patients (STBP-KAPQ) in China. BMC Infect Dis 18, 213 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3122-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3122-9